K2

This article needs copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone or spelling. (February 2024) |

| K2 | |

|---|---|

K2 from Broad Peak Base Camp | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) Ranked 2nd |

| Prominence | 4,020 m (13,190 ft) Ranked 22nd |

| Isolation | 1,316 km (818 mi) |

| Listing | Eight-thousander Seven Second Summits Ultra |

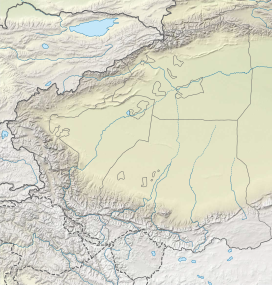

| Coordinates | 35°52′57″N 76°30′48″E / 35.88250°N 76.51333°E[2] |

| Geography | |

| Countries |

|

| Parent range | Karakoram |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 31 July 1954 Achille Compagnoni & Lino Lacedelli |

| Easiest route | Abruzzi Spur |

| |

K2 is the second-highest mountain in the world, at 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) tall. It is also known as Mount Godwin-Austen or Chhogori (ཆོགོ་རི།).[3] K2 is part of the Karakoram mountain range, and is found in the Kashmir, Pakistan region. The name, 'K2' came from the first survey of Karakoram range. In the survey, surveyors named each mountain with a 'K' and a number after that. [3][4]

K2 is known as the 'Savage Mountain' and is thought to be harder to climb than Mount Everest, the highest mountain in the world.[5] It has the second-highest accidental death rate among the 8,000-metre mountains. One person dies for every four who reach the top.[6] As of 2011, only 300 people have climbed to the top of the mountain, and at least 80 of them have died trying to climb it.[5]For both situations, K2 has been climbed during the winter and summer.[7]

The top of the mountain was first reached in 1954 by Italian climbers Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni.[8]

Name

[change | change source]The name K2 was first used by the Great Trigonometrical Survey of British India. Thomas Montgomerie made the first survey of the Karakoram range from Mount Harmukh. The mountain was 210 km (130 miles) to the south of K2. At the time, he sketched the two most prominent peaks and called them K1 and K2.[9]

The rule of the Great Trigonometrical Survey was to use local names for mountains when possible. K1 was locally known as Masherbrum. K2, however, appeared not to have a local name. The reason was probably its remoteness. It cannot be seen from Askole, the last village to the south, or from the nearest village to the north. It is believed few local people saw K2 from where it is visible.[9] People think that the name 'Chogori' is the rightful local name for K2. 'Chogori' comes from two Balti words, chhogo ("big") and ri ("mountain") (ཆོགོ་རི།)[10] [11] There is not much evidence for its widespread use, however. It may have been invented by Western explorers.[12] It does form the basis for the name Qogir (simplified Chinese: 乔戈里峰; traditional Chinese: 喬戈里峰; pinyin: Qiáogēlǐ Fēng) which the Chinese government uses as the official name of the mountain.

As the mountain did not have a local name, the name Mount Godwin-Austen was suggested. This was in honor of Henry Godwin-Austen, who had been an early explorer of the area. While the name was rejected by the Royal Geographical Society,[9] it was used on several maps and is still used.[13][14]

To this day, the mountain is still known as K2. This name now exists in the Balti language as Kechu or Ketu (ཀེ་ཆུ།).[12] The Italian climber Fosco Maraini stated that while the name K2 came by chance, is was good for the mountain. He said:

... just the bare bones of a name, all rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human. It is atoms and stars. It has the nakedness of the world before the first man – or of the cindered planet after the last.[15]

Climbing history

[change | change source]Early attempts

[change | change source]

The mountain was first surveyed by a European team in 1856. Team member Thomas Montgomerie first called the mountain K2. The other mountains were originally named K1, K3, K4, and K5, but were later changed to local names.[16] In 1892, Martin Conway led a British expedition that made it to the Baltoro Glacier.[17]

The first real attempt to climb K2 was made in 1902 by an Anglo-Swiss expedition. It took fourteen days for them to reach the foot of the mountain.[18] After five attempts, the team only made it to 6,525 metres (21,407 ft).[19]

The next expedition was in 1909. It was led by the Italian Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi. This team made it only to an elevation of 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the Southeast Spur of the mountain. Not finding any other routes, the Duke said that K2 would never be climbed.[9]

The next attempt was not made until 1938. At that time, American Charles Houston took an expedition to the mountain. They decided that the Abruzzi Spur was the best route and made it to a height of around 8,000 metres (26,000 ft).[20]

In 1939, an American expedition led by Fritz Wiessner came within 200 metres (660 ft) of the summit. It ended in disaster when four members died on the mountain.[21]

Charles Houston tried again in 1953. The try was a failure due to a storm, which trapped the team for 10 days at 7,800 metres (25,590 ft). One climber died in the expedition. Many others nearly died in a mass fall but were saved by Pete Schoening.[22]

First success

[change | change source]

Finally, in 1954, an Italian expedition made it to the summit. It was lead by geologist Ardito Desio. The two climbers to reach the top were Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, at 6pm on 31 July 1954. One member of the expedition (Colonel Muhammad Ata-Ullah of Pakistan) had been part of the 1953 American attempt as well. Other members were scientists, a doctor, a photographer, and others. Mario Puchoz died in the attempt. Two other members had to be hospitalized and one had to have his toes amputated due to frostbite.[23]

Later success

[change | change source]The second success was not until 23 years after the first. It was a Japanese expedition lead by Ichiro Yoshizawa in 1977.[9]

The third success was in 1978, and used a different route from the first two. This one was done by an American team, lead by James Whittaker.[24]

Another notable success was in 1982, when a Japanese team climbed from the harder Chinese side of the mountain. The previous successes had been from the Pakistan side. The expedition was lead by Makoto Shinkai and Masatsugo Konishi. Three members of the team made it to the summit on 14 August. One of them, however, died on when coming down. Four other members made it to the summit the next day, on 15 August.[25]

The first person to reach the summit twice was Czech climber Josef Rakoncaj. He was part of a 1983 Italian expedition that made the summit. Then three years later he made the summit again as part of an international expedition.[26]

The first woman to reach the summit was Polish climber Wanda Rutkiewicz in 1986. Two other women reached the summit later that same day, but died when coming down.[27]

In 1986, Benoit Chamoux used 23 hours to climb (from base camp) to the mountain top.[28] He climbed without oxygen bottles.

In 2004, the Spanish climber Carlos Soria Fontán became the oldest person ever to summit K2, at the age of 65.[29]

In 2018, Polish climber Andrzej Bargiel became the first person to ski down K2 after he made it to the top.[30]

In 2022, Chhiring Sherpa climbed the mountain in 12 hours and 20 minutes.[28] He used oxygen bottles.

Around 700 people have climbed (as of August 2022) to the summit of K2. 190 of those (climbs or) ascents, were in 2022.[31][5]

Climbing difficulty

[change | change source]Even though the summit of Everest is higher, K2 is much more difficult and dangerous climb.[32] This is because of its worse weather. It is believed by many to be the world's most difficult and dangerous to climb. This is why it is nicknamed "The Savage Mountain".[33]The popularity was mentioned of the Mount Everest, which is much higher than the popularity or vanity of K2. At least 80 (as of September 2010) people have died attempting the climb.

Investigation of the death of a porter (2023)

[change | change source]In August 2023, Pakistani authorities started to investigate the death of Mohammed Hassan. Media said that "dozens of climbers" that wanted "to reach the summit [or top of the mountain] had walked past the man after he was [...] injured in a fall." He died a few hours later on the mountain.[34]

Video clips have been published by many news websites. Media says that video clips show climbers stepping or walking over the injured man without trying to help him.[34]

Wilhelm Steindl, a mountain climber, said that "If I or any other Westerner [or people from the Western world] had been lying there, [then] everything would have been done to save them", and "Everyone would have had to turn back to bring the injured person back down to the valley".[34]

Only one witness has talked with the police, according to media (August 15). He says that climbers were jumping and straddling over the injured porter that was dying on the path.[35] (A porter is a person who carries things (or cargo) for others.)

The police of Gilgit-Baltistan are doing the investigation.[34] The military and the department of tourism have jurisdiction where the porter died. Furthermore, the government of Gilgit-Baltistan created a committee (or group) of 5 people that have made a report. The report "will be made public" [...] "a few days after August 30.[36] The report must be given [around August 23 or] within 15 days of August 7.[37]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "K2". Peakbagger.com.

- ↑ "Karakoram and India/Pakistan Himalayas Ultra-Prominences". peaklist.org. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "K2 Chhoghori The King of Karakoram". Skardu.pk. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "K2: Love for the most dreaded mountain in the world". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Brummit, Chris (16 December 2011). "Russian team to try winter climb of world's 2nd-highest peak". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ Woodward, Aylin (30 May 2019). "At least 11 people died on Mount Everest last week. But it's just the 10th-deadliest mountain in the Himalayas". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ↑ "Stairway to heaven". The Economist. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Ashish (2023-10-30). "Achille Compagnoni & Lino Lacedelli: First Italian Expeditioner To K2 In 1954". trekebc.com. Archived from the original on 2024-04-18. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-66007-2.

- ↑ "Convert Roman into Urdu Script". changathi.com.

- ↑ "Place names – II". The Express Tribune. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Carter, H. Adams (1983). "A Note on the Chinese Name for K2, "Qogir"". Notes. American Alpine Journal. Vol. 25, no. 57. American Alpine Club. p. 296. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ "Pakistan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Carter, H. Adams (1975). "Balti Place Names in the Karakoram". Feature Article. American Alpine Journal. Vol. 20, no. 1. American Alpine Club. pp. 52–53. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

Godwin Austen is the name of the glacier at its eastern foot and is only incorrectly used on some maps as the name of the mountain.

- ↑ Maraini, Fosco (1961). Karakoram: the ascent of Gasherbrum IV. Hutchinson.

- ↑ Kenneth Mason (1987 edition) Abode of Snow p.346

- ↑ Houston, Charles S. (1953). K2, the Savage Mountain. McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ "Confessions of Aleister Crowley, Chapter 16". hermetic.com. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ↑ "A timeline of human activity on K2". k2climb.net. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ↑ Houston, Charles S; Bates, Robert (1939). Five Miles High (2000 Reprint by First Lyon Press, with introduction by Jim Wickwire ed.). Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-1-58574-051-2.

- ↑ Kaufman, Andrew J.; Putnam, William L. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-323-9.

- ↑ Houston, Charles S; Bates, Robert (1954). K2 – The Savage Mountain (2000 Reprint by First Lyon Press with introduction by Jim Wickwire ed.). Mc-Graw-Hill Book Company Inc. ISBN 978-1-58574-013-0.

- ↑ "Amir Mehdi: Left out to freeze on K2 and forgotten". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ Reichardt, Louis F. (1979). "K2: The End of a 40-Year American Quest". Feature Article. American Alpine Journal. 22 (1). American Alpine Club: 1–18. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ "K2, North Ridge". American Alpine Journal. 25 (57). American Alpine Club: 295. 1983. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ Rakoncaj, Josef (1987). "Broad Peak and K2". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. 29 (61). American Alpine Club: 274. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ "K2, Women's Ascents and Tragedy". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. 29 (61). American Alpine Club: 273. 1987. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "K2 Speed Ascent Records: Who Wears the Crown? » Explorersweb". 6 August 2022. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ↑ "Dozens Reach Top of K2". climbing.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013.

- ↑ "First Ski descent on K2". dreamwanderlust.com. 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Is K2, the "Savage Mountain," Becoming Less Savage?". 17 August 2022. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ↑ "The Big Question: What makes K2 the most perilous challenge a mountaineer can face?". The Independent. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

It's enormous, very high, incredibly steep and much further north than Everest which means it attracts notoriously bad weather...Although Everest is 237m taller, K2 is widely perceived to be a far harder climb. "It's a very serious and very dangerous mountain," adds Sir Chris. "No matter which route you take it's a technically difficult climb, much harder than Everest. The weather can change incredibly quickly, and in recent years the storms have become more violent.

- ↑ Worrall, Simon (13 December 2015). "Why K2 Brings Out the Best and Worst in Those Who Climb It". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 "Mohammed Hassan death: Investigation launched after Kristin Harila's record-breaking summit of K2 dogged by allegations climbers left Pakistani porter to die". Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ↑ "Erfaren klatrer om K2-ulykken: – Ekspedisjonslederen burde etterforskes". 14 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ↑ "Inquiry into death of Pakistani porter at K2 clears Norwegian climber". Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ↑ "Familien vil hente ned kroppen". 16 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

Other websites

[change | change source]- Map of K2

- 'K2: The Killing Peak' Men's Journal November 2008 feature

- Story of the 1902 K2 expedition by Aleister Crowley, who was in the group

- The climbing history of K2 from the first attempt in 1902 until the Italian success in 1954.

- The climbing history of K2 from the first attempt in 1902 until the Italian success in 1954.