리신

Lysine

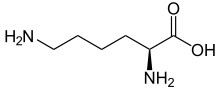

L-리신의 골격식 | |||

| | |||

| 이름 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC 이름 (2S)-2,6-다이아미노헥사노산(L-리신)-2R-2,6-다이아미노헥사노산(D-리신) | |||

| 기타 이름 Lysine, D-Lysine, L-Lysine, LYS, h-Lys-OH | |||

| 식별자 | |||

3D 모델(JSmol) |

| ||

| 체비 | |||

| 켐벨 | |||

| 켐스파이더 | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.673 | ||

| 케그 | |||

펍켐 CID | |||

| 유니 |

| ||

| |||

| |||

| 특성. | |||

| C6H14N2O2 | |||

| 어금질량 | 146.168 g·190−1 | ||

| 1.5 kg/L | |||

| 약리학 | |||

| B05XB03(WHO) | |||

| 부가자료페이지 | |||

| 라이신(데이터 페이지) | |||

달리 명시된 경우를 제외하고, 표준 상태(25°C [77°F], 100 kPa)의 재료에 대한 데이터가 제공된다. | |||

| Infobox 참조 자료 | |||

리신(Symbol Lys 또는 K)[2]은 단백질의 생합성에 사용되는 α-아미노산이다.α-아미노 그룹(생물학적 조건에서 양성 -NH3+ 형태), α-카르복실산 그룹(생물학적 조건에서 감응 -COO− 형태), 사이드 체인 리실((CH2)4NH2)을 포함하고 있으며, 이를 기본 충전(생리학적 pH), 알리프아미노산(aliphatic ac미노산)으로 분류한다.그것은 AAA와 AAG에 의해 암호화되어 있다.거의 모든 다른 아미노산과 마찬가지로 α-탄소도 키랄이며 리신은 에반토머 또는 둘 다의 인종 혼합물을 가리킬 수 있다.이 글의 목적상, 리신은 생물학적으로 활성 에반토머 L-리신(α-탄소가 S 구성에 있는 경우)을 가리킨다.

인체는 리신을 합성할 수 없다.그것은 인간에게 필수적이며 식단에서 얻어야 한다.리신을 합성하는 유기체에서는 두 가지 주요 생합성 경로인 디아미노피멜레이트(diaminopimelate)와 α-아미노아디페이트(α-aminoadipate) 경로를 가지고 있는데, 이 경로는 뚜렷한 효소와 기판을 채용하고 있으며 다양한 유기체에서 발견된다.리신 카타볼리즘은 여러 경로 중 하나를 통해 발생하는데, 그 중 가장 흔한 것이 사카로핀 경로다.

리신은 인간에게 있어서, 가장 중요한 것은 단백질 발생이지만, 콜라겐 폴리펩타이드의 교차 링크, 필수 미네랄 영양소의 섭취, 지방산 신진대사의 핵심인 카르니틴의 생산에서도 여러 역할을 한다.리신은 히스톤 수정에도 관여하는 경우가 많아 후생유전자에 영향을 미친다.ε아미노 그룹은 종종 수소 결합에 참여하며 촉매의 일반적인 기반으로서 참여한다.ε암모늄군(NH3+)은 카복실군(C=OOh)에 부착된 α-탄소의 네 번째 탄소에 부착된다.[3]

몇몇 생물학적 과정에서의 그것의 중요성 때문에, 라이신의 부족은 결점 조직, 지방산 신진대사, 빈혈, 그리고 전신 단백질 에너지 결핍을 포함한 여러 질병 상태를 초래할 수 있다.이와는 대조적으로, 효과적이지 않은 강직증으로 인한 라이신의 과다 섭취는 심각한 신경 질환을 일으킬 수 있다.

라이신은 1889년 독일의 생물 화학자 페르디난드 하인리히 에드먼드 드렉셀에 의해 우유 속의 단백질 카제인으로부터 처음 격리되었다.[4]그는 그것을 "라이신"이라고 이름 지었다.[5]1902년 독일의 화학자 에밀 피셔와 프리츠 바이거트는 라이신의 화학구조를 합성하여 결정하였다.[6]

생합성

리신 합성을 위한 두 가지 경로가 자연에서 확인되었다.디아미노피멜레이트(DAP) 경로는 아스파리트 유도 생합성 계열에 속하며, 이 계열은 트레오닌, 메티오닌, 이솔레우신 합성에도 관여한다.[7][8]반면 α-아미노아디페이트(AAA) 통로는 글루탐산염 생합성 계열의 일부다.[9][10]

The DAP pathway is found in both prokaryotes and plants and begins with the dihydrodipicolinate synthase (DHDPS) (E.C 4.3.3.7) catalysed condensation reaction between the aspartate derived, L-aspartate semialdehyde, and pyruvate to form (4S)-4-hydroxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-(2S)-dipicolinic acid (HTPA).[11][12][13][14][15]그런 다음 NAD(P)H를 양성자 공여자로 하여 디하이드로디피콜린제 환원효소(DHDPR) (E.C 1.3.1.26)에 의해 제품이 감소하여 2,3,4,5-테트라하이드로디폴린트(THDP)를 산출한다.[16]이때부터 아세틸라제, 아미노트란스페라제, 탈수소효소, 숙시닐라제 경로 등 4가지 경로변형이 발견되었다.[7][17]아세틸라아제와 숙시닐라아제 변종경로는 모두 4개의 효소 카탈리시스 단계를 사용하며, 아미노트란스페라제 경로로는 2개의 효소를 사용하며, 탈수소효소 경로로는 1개의 효소를 사용한다.[18]이 네 가지 변형 경로는 Penultimate 제품인 meso-diaminophimelate의 형성에 수렴하며, 이후 DAPDC (E.C 4.1.1.20)에 의해 강직되는 되돌릴 수 없는 반응으로 효소 분해되어 L-리신을 생산한다.[19][20]DAP 경로는 초기 DHDPS 카탈리시스 응축 단계뿐만 아니라 아스파테이트 처리와 관련된 효소의 업스트림을 포함하여 여러 수준에서 규제된다.[20][21]라이신은 이러한 효소에 강한 부정적인 피드백 루프를 전달하고, 그 후에 전체 경로를 조절한다.[21]

AAA 경로에는 L-리신 합성을 위한 중간 AAA를 통한 α-케토글루타레이트 및 아세틸-CoA의 응결이 포함된다.이 통로는 양성자와 고 균류뿐만 아니라 여러 효모종에도 존재하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[10][22][23][24][25][26][27]또한 AAA 노선의 대체 변종이 테르무스 보온병(Thermus thermophilus)과 피로코커스 호리코시이(Pyrococcus horikosii)에서 발견되었다고 보고되었는데, 이는 이 경로가 원래 제안된 것보다 원핵생물에서 더 널리 퍼져 있음을 나타낼 수 있다.[28][29][30]The first and rate-limiting step in the AAA pathway is the condensation reaction between acetyl-CoA and α‑ketoglutarate catalysed by homocitrate-synthase (HCS) (E.C 2.3.3.14) to give the intermediate homocitryl‑CoA, which is hydrolysed by the same enzyme to produce homocitrate.[31]Homocitrate는 homoaconitase (HAC) (E.C 4.2.1.36)에 의해 효소적으로 탈수되어 cis-homoocitate를 산출한다.[32]그리고 나서 HAC는 시스호모콘테이트가 호모아시토시트레이트를 생산하기 위해 수압을 받는 두 번째 반응을 촉진한다.[10]결과물은 호모아소시레이트 탈수소효소(HIDH) (E.C 1.1.1.87)에 의해 산화 데카복시화를 거쳐 α-케토아디페이트를 산출한다.[10]그런 다음 AAA는 글루탐산염을 아미노기증자로 사용하여 피리독산 5′-인산염(PLP) 의존 아미노트란스페라제(PLP-AT) (E.C 2.6.1.39)를 통해 형성된다.[31]이때부터 AAA의 통로는 왕국의 [여기에 뭔가가 없어? -> 적어도 섹션 헤더! ]에 따라 달라진다.균류에서 AAA는 AAA 환원효소(E.C 1.2.1.95)를 통해 인포판테이트비닐전달효소(E.C 2.7.8.7)에 의해 활성화되는 아데닐화 및 환원 모두를 포함하는 고유 공정에서 α-아미노아디페이트-세미알데히드로 감소한다.[10]세미알데히드가 형성되면 사카로핀 환원효소(E.C 1.5.1.10)는 양성자 공여자로서 글루탐산염과 NAD(P)H로 응축 반응을 촉진하고, 이미인은 감량하여 페놀티메이트 제품인 사카로핀을 생산한다.[30]균류에서 경로의 마지막 단계는 사카로핀 탈수소효소(SDH) (E.C 1.5.1.8)의 촉매 산화 탈염으로 L-리신(L-Lysine)이 발생한다.[10]일부 원핵생물에서 발견되는 변형 AAA 경로에서 AAA는 먼저 인산염화 후 ε-알데히드로 환원되는 N-아세틸-α-아미노아디페이트로 변환된다.[30][31]알데히드는 N-아세틸-리신(N-acetyl-Lysine)에 전이되며, N-아세틸-리신(L-리신)을 공급하기 위해 탈산된다.[30][31]그러나 이 변종 경로에 관여하는 효소는 추가적인 검증이 필요하다.

카타볼리즘

모든 아미노산과 마찬가지로 리신의 카타볼리즘은 식이 요법의 리신을 섭취하거나 세포내 단백질의 분해로부터 시작된다.카타볼리즘은 프리 리신의 세포내 농도를 조절하고, 과도한 프리 리신의 독성 효과를 막기 위해 안정 상태를 유지하는 수단으로도 사용된다.[33]리신 카타볼리즘에 관련된 몇 가지 경로가 있지만, 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 것은 사카로핀 경로로 주로 동물의 간(및 이에 상응하는 장기)에서, 특히 미토콘드리아 내에서 일어난다.[34][33][35][36]이것은 앞에서 설명한 AAA 경로의 역이다.[34][37]In animals and plants, the first two steps of the saccharopine pathway are catalysed by the bifunctional enzyme, α-aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase (AASS), which possess both lysine-ketoglutarate reductase (LKR) (E.C 1.5.1.8) and SDH activities, whereas in other organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, both of these enzymes are encoded by separate첫 [38][39]번째 단계는 사카로핀을 생산하기 위해 α-케토글루타레이트(α-ketoglutarate)가 존재하는 L-리신의 L-KR 카탈리신 감소와 관련된 것으로, NAD(P)H는 양성자 기증자의 역할을 한다.[40]사카로핀은 이후 NAD가+ 있는 곳에서 SDH에 의해 강직된 탈수 반응을 일으켜 AAS와 글루탐산염을 생산한다.[41]그런 다음 AAS 탈수소효소(AASD)(E.C 1.2.1.31)는 분자를 AAA로 더 탈수시킨다.[40]이후 PLP-AT는 AAA 생합성 경로에 대한 역반응을 촉진하여 AAA가 α-케토아디페이트로 변환된다.제품인 α-케토아디페이트는 NAD와+ 코엔자임 A가 있는 곳에서 디카복실화 되어 글루타릴-CoA를 생산하지만, 이에 관련된 효소는 아직 완전히 해명되지 않았다.[42][43]일부 증거는 옥소글루타레이트 탈수소효소 복합체(OGDHc)(E.C 1.2.4.2)의 E1 서브유닛에 구조적으로 동질인 2-옥소아디프탈수소효소 복합체(OADHc)가 데카복시화 반응에 책임이 있음을 시사한다.[42][44]Finally, glutaryl-CoA is oxidatively decarboxylated to crotonyl-CoA by glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (E.C 1.3.8.6), which goes on to be further processed through multiple enzymatic steps to yield acetyl-CoA; an essential carbon metabolite involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA).[40][45][46][47]

영양가치

리신은 인간에게 필수적인 아미노산이다.[48]인간의 영양 요구량은 유아기의 ~60mg·kg−1·d부터−1 성인의 경우 ~30mg·kg−1·d까지−1 다양하다.[34]이 요건은 일반적으로 서양 사회에서 권장 요건을 훨씬 초과하여 고기와 야채 소스로부터 라이신을 섭취하는 경우에 충족된다.[34]채식주의 식단에서 리신은 육류원에 비해 곡물 작물의 리신의 양이 제한되어 섭취량이 적다.[34]

곡물 작물에서 리신의 농도가 제한되는 점을 감안할 때 유전자 변형 관행을 통해 리신의 함량을 높일 수 있을 것으로 오랫동안 추측해 왔다.[49][50]종종 이러한 관행은 DHDPS 효소의 리신 피드백에 민감하지 않은 직교법을 도입하는 방법으로 DAP 경로의 의도적인 조절 오류와 관련이 있다.[49][50]이러한 방법은 TCA 사이클에 대한 자유 리신 증가와 간접 효과의 독성 부작용 때문에 제한된 성공을 충족시켰다.[51]식물은 식물의 씨앗 속에 발견되는 씨앗 저장 단백질의 형태로 리신과 다른 아미노산을 축적하는데, 이는 곡물 작물의 식용 성분을 나타낸다.[52]이는 자유 리신을 증가시킬 뿐만 아니라, 리신을 안정적인 종자 저장 단백질 합성으로 유도하고, 이후 작물의 소모성분의 영양적 가치를 증가시킬 필요가 있음을 강조한다.[53][54]유전자 변형 관행이 제한적인 성공에 도달한 반면, 보다 전통적인 선택적 번식 기술은 필수 아미노산인 리신과 트립토판 함량이 현저히 증가된 '품질 단백질 메이지'의 격리를 허용했다.이러한 라이신 함량의 증가는 불투명-2 돌연변이로 리신-래킹 제인 관련 종자 저장 단백질의 전사를 감소시켰고, 그 결과 리신이 풍부한 다른 단백질의 풍부함을 증가시켰기 때문이다.[54][55]일반적으로 가축사료에서 리신의 제한된 풍부함을 극복하기 위해 산업적으로 생산되는 리신을 첨가한다.[56][57]산업 과정에는 코리네박테리움 글루타미늄의 발효 배양과 그에 따른 리신 정화가 포함된다.[56]

식재료

리신의 좋은 공급원은 달걀, 고기(특히 붉은 고기, 양고기, 돼지고기, 가금류), 콩, 완두콩, 치즈(특히 파르메산), 특정 생선(대구와 정어리 등)과 같은 고단백 식품이다.[58]리신은 대부분의 곡물에서 제한적인 아미노산(특정 식품에서 가장 적은 양으로 발견되는 필수 아미노산)이지만 대부분의 펄스(레기움)에서는 풍부하다.[59]채식이나 낮은 동물성 단백질 식단은 곡물과 콩류 모두를 포함한다면 라이신을 포함한 단백질에 적합할 수 있지만, 두 식품군을 같은 식사에 섭취할 필요는 없다.

식품은 단백질 1g당 최소 51mg의 리신을 함유하고 있다면(단백질이 5.1% 리신인 경우) 충분한 리신을 함유하고 있는 것으로 간주된다.[60]L-리신 HCl은 80.03% L-리신을 공급하는 식이요법 보조제로 사용된다.[61]이와 같이 L-리신 HCl 1.25 g에 1 g의 L-리신이 포함되어 있다.

생물학적 역할

리신의 가장 흔한 역할은 단백질 생성이다.리신은 단백질 구조에서 중요한 역할을 자주 한다.사이드 체인은 한쪽 끝에 양전하를 띤 그룹과 등뼈에 가까운 긴 소수성 탄소 꼬리를 포함하고 있어 리신은 어느 정도 암페타성으로 간주된다.이 때문에 리신은 용제 통로나 단백질 외관에서도 더 흔할 뿐만 아니라 매장되어 있는 것을 발견할 수 있으며, 수성 환경과 상호작용을 할 수 있다.[62]리신은 its아미노 그룹이 수소 본딩, 소금 브리지, 공밸런트 상호작용에 자주 참여하여 쉬프 기지를 형성하기 때문에 단백질 안정에도 기여할 수 있다.[62][63][64][65]

리신의 두 번째 주요 역할은 히스톤 수정에 의한 후생유전적 규제에 있다.[66][67]히스톤의 돌출된 꼬리에서 발견되는 리신 잔류물을 수반하는 여러 종류의 공밸런트 히스톤 수정법이 있다.수정사항에는 아세틸리신(-CHCO3)을 형성하거나 리신(-CH3), 최대 3개의 메틸(-CH), 유비퀴틴 또는 스모 단백질군이 추가 또는 제거되는 경우가 많다.[66][68][69][70][71]다양한 수정은 유전자가 활성화되거나 억제될 수 있는 유전자 조절에 다운스트림 효과를 준다.

라이신은 또한 결합조직의 구조 단백질, 칼슘 동종분해, 지방산 대사를 포함한 다른 생물학적 과정에 중요한 역할을 하도록 연루되었다.[72][73][74]리신은 콜라겐에 들어 있는 3개의 헬리컬 폴리펩타이드 사이의 교차 연계에 관여하여 안정성과 인장 강도를 얻는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[72][75]이 메커니즘은 박테리아 세포벽에서 리신의 역할과 유사하며, 리신(및 메소-다이아미노피멜레이트)은 교차 링크 형성에 중요하며, 따라서 세포벽의 안정성에 중요하다.[76]이 개념은 이전에 잠재적으로 병원성 유전자 변형 박테리아의 원치 않는 방출을 피하기 위한 수단으로 탐구되어 왔다.DAP의 보완 없이는 균주가 생존할 수 없어 실험실 환경 밖에서 살 수 없기 때문에 모든 유전자 변형 관행에 보조성 대장균(X1776)을 사용할 수 있다고 제안했다.[77]리신은 또한 칼슘 장 흡수 및 신장 유지에 관여하도록 제안되어 왔으며, 따라서 칼슘 근위축에 역할을 할 수도 있다.[73]마지막으로 리신은 지방산을 미토콘드리아로 수송하는 카르니틴의 전구체로 밝혀졌는데, 그 곳에서 에너지 방출을 위해 산화시킬 수 있다.[74][78]카르니틴은 특정 단백질의 분해 산물인 트리메틸리신으로부터 합성되는데, 그러한 리신은 먼저 단백질에 통합되어 메틸화 되어야 카르니틴으로 전환된다.[74]그러나 포유류에서 카르니틴의 1차 공급원은 리신 변환을 통해서가 아니라 식이 공급원을 통해서이다.[74]

로돕신이나 시각적 옵신(OPN1SW, OPN1MW, OPN1LW 유전자에 의해 인코딩됨)과 같은 opsin에서는 레티날알데히드가 리신 잔여물을 보존한 Schiff 베이스를 형성하고, 레티닐리덴 그룹과의 빛의 상호작용으로 인해 색시력에서 신호 전도가 발생한다(자세한 내용은 시각 사이클 참조).

논란이 있는 역할

리신을 정맥 또는 구두로 투여할 경우 성장 호르몬의 분비를 현저하게 증가시킬 수 있다는 오랜 논의가 있었다.[79]이로 인해 운동선수들은 훈련 중 근육 성장을 촉진하기 위한 수단으로 라이신을 사용하게 되었으나, 현재까지 라이신의 이 사용을 뒷받침할 중요한 증거가 발견되지 않았다.[79][80]

헤르페스 심플렉스 바이러스(HSV) 단백질은 아르기닌이 더 풍부하고 리신은 감염 세포보다 더 열악하기 때문에 리신 보충제를 치료제로 사용해 왔다.이 두 아미노산은 장에서 흡수되어 신장에서 재생되고 동일한 아미노산 전달체에 의해 세포로 이동되기 때문에, 리신의 풍부함은 이론적으로 바이러스 복제가 가능한 아르기닌의 양을 제한할 것이다.[81]임상 연구는 예방적 효과나 HSV 발병에 대한 치료에서 좋은 증거를 제공하지 않는다.[82][83]리신이 HSV에 대한 면역 반응을 향상시킬 수 있다는 제품 주장에 대해, 유럽 식품안전청(European Food Safety Authority)의 검토 결과 인과관계의 증거는 발견되지 않았다.2011년에 발표된 같은 리뷰는 라이신이 콜레스테롤을 낮추고, 식욕을 증가시키며, 일반 영양소 이외의 역할에서 단백질 합성에 기여하거나, 칼슘 흡수나 보유를 증가시킬 수 있다는 주장을 뒷받침하는 증거를 발견하지 못했다.[84]

질병에서의 역할

리신과 관련된 질병은 리신의 다운스트림 처리, 즉 단백질로의 결합이나 대체 생체분자로의 변형 등의 결과물이다.콜라겐에서 리신의 역할은 위에서 간략히 설명되었지만, 콜라겐 펩타이드의 교차연결에 관여하는 리신과 히드록실리신의 부족은 결합조직의 질병 상태와 연관되어 있다.[85]카르니틴은 지방산 대사에 관여하는 리신 유래 주요 대사물인 만큼, 충분한 카르니틴과 라이신이 부족한 표준 이하의 식단은 카르니틴 수치를 감소시켜 개인의 건강에 상당한 연쇄효과를 줄 수 있다.[78][86]리신은 또한 철분 섭취에 영향을 주고, 그 결과 혈장에 페리틴의 농도에 영향을 미치는 것으로 의심되기 때문에 빈혈에도 역할을 하는 것으로 나타났다.[87]그러나 정확한 행동 메커니즘은 아직 해명되지 않았다.[87]가장 일반적으로, 리신 결핍은 서구의 사회에서 나타나고 단백질 에너지 영양실조로 나타나며, 이는 개인의 건강에 심오하고 전신적인 영향을 미친다.[88][89]또한 리신 카타볼리즘을 일으키는 효소의 돌연변이, 즉 사카로핀 경로의 분기성 AAS 효소를 수반하는 유전적 유전병도 있다.[90]리신 카타볼리즘이 부족하여 혈장에 아미노산이 축적되고 환자가 고혈당증(hylyssinia)이 발생하는데, 간질, 아탁시아, 가소성, 심신장애 등 중증 신경장애에 무증상으로 나타날 수 있다.[90][91]고신혈증의 임상적 중요성은 신체적 또는 정신적 장애와 고신혈증 사이의 상관관계가 발견되지 않는 일부 연구와 함께 현장에서 논의의 대상이 된다.[92]이와 더불어 리신 대사 관련 유전자의 돌연변이는 피리독신 의존성 간질혈증(ALDH7A1유전자), α-케토아디피치피치피치피치피증(DHTKD1유전자), 글루타산뇨증 타입 1(GCD유전자) 등 여러 질환 상태에 관여해 왔다.[42][93][94][95][96]

고혈당뇨는 소변에서 많은 양의 리신(Lysis는 소변에서 많은 양의 리신을 가지고 있다.[97]리신 분해에 관여하는 단백질이 유전적 돌연변이로 인해 기능하지 못하는 대사질환에 의한 경우가 많다.[98]그것은 또한 신장관 운송의 실패로 인해 발생할 수 있다.[98]

동물 사료에 리신 사용

동물 사료용 라이신 생산량은 2009년에 12억 2천만 유로가 넘는 시장가치로 거의 70만 톤에 달할 정도로 세계적인 주요 산업이다.[99]리신은 육류 생산을 위해 돼지와 닭 등 특정 동물의 성장을 최적화할 때 제한적인 아미노산이기 때문에 동물 사료에 중요한 첨가물이다.라이신 보충제는 높은 성장률을 유지하면서 저비용 식물 단백질(예를 들어 콩보다는 maize)을 사용할 수 있도록 하고 질소 배설으로 인한 오염을 제한한다.[100]그러나 결국 인산염 오염은 옥수수를 가금류와 돼지의 사료로 사용할 때 주요한 환경 비용이다.[101]

리신은 미생물 발효에 의해 산업적으로 생산되며, 주로 설탕의 기초에서 생산된다.유전자 공학 연구는 생산 효율을 향상시키고 다른 기판으로부터 라이신을 만들 수 있도록 하기 위해 박테리아 균주를 적극적으로 추구하고 있다.[99]

대중문화에서

1993년 영화 쥬라기 공원(1990년 동명 마이클 크라이튼 소설 원작)에는 공학적 보조생리의 한 예인 라이신을 생산할 수 없도록 유전자 조작을 한 공룡이 등장한다.[102]이것은 "라이신 보정"으로 알려져 있었고, 복제된 공룡들이 공원 밖에서 살아남는 것을 막기 위해 공원 수의사 직원들이 제공하는 라이신 보충제에 의존할 수밖에 없었다.현실적으로 리신을 생산할 수 있는 동물은 없다(필수 아미노산이다).[103]

1996년 라이신은 미국 역사상 가장 큰 가격 담합 사건의 초점이 되었다.Archer Daniels Midland Company는 1억 달러의 벌금을 냈고, 그 회사 임원들 중 3명이 유죄를 선고받고 복역했다.가격 담합 사건에서도 유죄 판결을 받은 곳은 일본 기업 2곳(아지노모토, 교와하코)과 한국 기업(세원)이다.[104]공모자들이 라이신 가격을 담합한 비밀 동영상 녹취록은 온라인이나 미국 법무부의 반독점법률부 등에 의뢰해 확인할 수 있다.이 사건은 영화 '제보자!'의 기본이 되었고, 동명의 책이 되었다.[105]

참조

![]() 본 기사는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스(2018)에 따라 다음과 같은 출처에서 개작되었다(검토자 보고서). Cody J Hall; Tatiana P. Soares da Costa (1 June 2018). "Lysine: biosynthesis, catabolism and roles" (PDF). WikiJournal of Science. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.15347/WJS/2018.004. ISSN 2470-6345. Wikidata Q55120301.

본 기사는 CC BY 4.0 라이센스(2018)에 따라 다음과 같은 출처에서 개작되었다(검토자 보고서). Cody J Hall; Tatiana P. Soares da Costa (1 June 2018). "Lysine: biosynthesis, catabolism and roles" (PDF). WikiJournal of Science. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.15347/WJS/2018.004. ISSN 2470-6345. Wikidata Q55120301.

- ^ a b Williams, P. A.; Hughes, C. E.; Harris, K. D. M (2015). "L‐Lysine: Exploiting Powder X‐ray Diffraction to Complete the Set of Crystal Structures of the 20 Directly Encoded Proteinogenic Amino Acids". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (13): 3973–3977. doi:10.1002/anie.201411520. PMID 25651303.

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). Nomenclature and symbolism for amino acids and peptides. Recommendations 1983". Biochemical Journal. 219 (2): 345–373. 15 April 1984. doi:10.1042/bj2190345. PMC 1153490. PMID 6743224.

- ^ 라이신. 애리조나 대학 생화학 분자생물물리학과 생물학 프로젝트.

- ^ Drechsel E(1889년)."벳술 Kenntniss Spaltungsprodukte 데 Caseïns der"[-LSB- 공헌]카세인 해결의 분할 제품의 지식[우리].저널 für 실천 Chemie.2시리즈(독일어로).39:425–429. doi:10.1002/prac.18890390135.페이지의 주 428일, Drechsel lysine – C8H16N2O2Cl2•PtCl4+H2O–의chloroplatinate 소금을 위해지만 소금의 결정 물 대신에 에탄올을 포함한 그는 나중에 이 방식을 틀렸다고 인정했다 실험식을 제시했다.안내인:Drechsel E(1891년)."데어 Abbau하는 Eiweissstoffe"[단백질의 분해].Archiv für Anatomie.;Drechsel E(1877년)Physiologie(독일어로):248–278 und."벳술 Kenntniss Spaltungsproducte 데 Caseïns der"[기여도]카세인의 분할 제품의 지식[우리]에](독일어로):254–260.p.부터 256:]"쭉 펼쳐져 다이 darin enthaltene 기지 모자 Formel C6H14N2O2 죽는다.데어 anfängliche Irrthum istdadurch veranlasst worden,dassdas Chloroplatinat nicht,wieangenommen 있는 병실은, Krystallwasser,sondern Krystallalkohol enthält, 때문에 "(다면 그 기지[그건]포함된 효력을 가지고 있는[경험적]공식 C6H14N2O2.초기 오류가 chloroplatinate 크리스탈(가정되어 왔다로)에 물을 담고 있지만 에탄올…){{ 들고 일기}}:Cite저널journal=( 도와 주)이 필요하지 않았기 때문이다.

- ^ Drechsel E(1891년)."데어 Abbau하는 Eiweissstoffe"[단백질의 분해].Archiv für Anatomie.;피셔 E(1891년)Physiologie(독일어로):248–278 und."Ueber Spaltungsproducte 데 Leimes neue"[젤라틴의 새로운 분열 제품에](독일어로):465–469.우편 469에서:]}:Cite저널journal=( 도와 주)필요로 한다(때문에 기본 C6H14N2O2, 이름"리신"으로 지정할 수 있으며,…)[참고:Drechsel의 에른스트 피셔는 대학원생.]{{ 들고 일기}"기지 C6H14N2O2,welchemit dem Namen Lysinwerden 반 페니 bezeichnet. 죽…".

- ^ Fischer E, Weigert F (1902). "Synthese der α,ε – Diaminocapronsäure (Inactives Lysin)" [Synthesis of α,ε-diaminohexanoic acid ([optically] inactive lysine)]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 35 (3): 3772–3778. doi:10.1002/cber.190203503211.

- ^ a b Hudson AO, Bless C, Macedo P, Chatterjee SP, Singh BK, Gilvarg C, Leustek T (January 2005). "Biosynthesis of lysine in plants: evidence for a variant of the known bacterial pathways". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1721 (1–3): 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.09.008. PMID 15652176.

- ^ Velasco AM, Leguina JI, Lazcano A (October 2002). "Molecular evolution of the lysine biosynthetic pathways". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 55 (4): 445–59. Bibcode:2002JMolE..55..445V. doi:10.1007/s00239-002-2340-2. PMID 12355264. S2CID 19460256.

- ^ Miyazaki T, Miyazaki J, Yamane H, Nishiyama M (July 2004). "alpha-Aminoadipate aminotransferase from an extremely thermophilic bacterium, Thermus thermophilus" (PDF). Microbiology. 150 (Pt 7): 2327–34. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27037-0. PMID 15256574. S2CID 25416966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Xu H, Andi B, Qian J, West AH, Cook PF (2006). "The alpha-aminoadipate pathway for lysine biosynthesis in fungi". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 46 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1385/CBB:46:1:43. PMID 16943623. S2CID 22370361.

- ^ Atkinson SC, Dogovski C, Downton MT, Czabotar PE, Dobson RC, Gerrard JA, Wagner J, Perugini MA (March 2013). "Structural, kinetic and computational investigation of Vitis vinifera DHDPS reveals new insight into the mechanism of lysine-mediated allosteric inhibition". Plant Molecular Biology. 81 (4–5): 431–46. doi:10.1007/s11103-013-0014-7. hdl:11343/282680. PMID 23354837. S2CID 17129774.

- ^ Griffin MD, Billakanti JM, Wason A, Keller S, Mertens HD, Atkinson SC, Dobson RC, Perugini MA, Gerrard JA, Pearce FG (2012). "Characterisation of the first enzymes committed to lysine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e40318. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...740318G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040318. PMC 3390394. PMID 22792278.

- ^ Soares da Costa TP, Muscroft-Taylor AC, Dobson RC, Devenish SR, Jameson GB, Gerrard JA (July 2010). "How essential is the 'essential' active-site lysine in dihydrodipicolinate synthase?". Biochimie. 92 (7): 837–45. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.03.004. PMID 20353808.

- ^ Soares da Costa TP, Christensen JB, Desbois S, Gordon SE, Gupta R, Hogan CJ, Nelson TG, Downton MT, Gardhi CK, Abbott BM, Wagner J, Panjikar S, Perugini MA (2015). "Quaternary Structure Analyses of an Essential Oligomeric Enzyme". Analytical Ultracentrifugation. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 562. pp. 205–23. doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2015.06.020. ISBN 9780128029084. PMID 26412653.

- ^ Muscroft-Taylor AC, Soares da Costa TP, Gerrard JA (March 2010). "New insights into the mechanism of dihydrodipicolinate synthase using isothermal titration calorimetry". Biochimie. 92 (3): 254–62. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2009.12.004. PMID 20025926.

- ^ Christensen JB, Soares da Costa TP, Faou P, Pearce FG, Panjikar S, Perugini MA (November 2016). "Structure and Function of Cyanobacterial DHDPS and DHDPR". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 37111. Bibcode:2016NatSR...637111C. doi:10.1038/srep37111. PMC 5109050. PMID 27845445.

- ^ McCoy AJ, Adams NE, Hudson AO, Gilvarg C, Leustek T, Maurelli AT (November 2006). "L,L-diaminopimelate aminotransferase, a trans-kingdom enzyme shared by Chlamydia and plants for synthesis of diaminopimelate/lysine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (47): 17909–14. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317909M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608643103. PMC 1693846. PMID 17093042.

- ^ Hudson AO, Gilvarg C, Leustek T (May 2008). "Biochemical and phylogenetic characterization of a novel diaminopimelate biosynthesis pathway in prokaryotes identifies a diverged form of LL-diaminopimelate aminotransferase". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (9): 3256–63. doi:10.1128/jb.01381-07. PMC 2347407. PMID 18310350.

- ^ Peverelli MG, Perugini MA (August 2015). "An optimized coupled assay for quantifying diaminopimelate decarboxylase activity". Biochimie. 115: 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.05.004. PMID 25986217.

- ^ a b Soares da Costa TP, Desbois S, Dogovski C, Gorman MA, Ketaren NE, Paxman JJ, Siddiqui T, Zammit LM, Abbott BM, Robins-Browne RM, Parker MW, Jameson GB, Hall NE, Panjikar S, Perugini MA (August 2016). "Structural Determinants Defining the Allosteric Inhibition of an Essential Antibiotic Target". Structure. 24 (8): 1282–1291. doi:10.1016/j.str.2016.05.019. PMID 27427481.

- ^ a b Jander G, Joshi V (1 January 2009). "Aspartate-Derived Amino Acid Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana". The Arabidopsis Book. 7: e0121. doi:10.1199/tab.0121. PMC 3243338. PMID 22303247.

- ^ Andi B, West AH, Cook PF (September 2004). "Kinetic mechanism of histidine-tagged homocitrate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Biochemistry. 43 (37): 11790–5. doi:10.1021/bi048766p. PMID 15362863.

- ^ Bhattacharjee JK (1985). "alpha-Aminoadipate pathway for the biosynthesis of lysine in lower eukaryotes". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 12 (2): 131–51. doi:10.3109/10408418509104427. PMID 3928261.

- ^ Bhattacharjee JK, Strassman M (May 1967). "Accumulation of tricarboxylic acids related to lysine biosynthesis in a yeast mutant". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 242 (10): 2542–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)95997-1. PMID 6026248.

- ^ Gaillardin CM, Ribet AM, Heslot H (November 1982). "Wild-type and mutant forms of homoisocitric dehydrogenase in the yeast Saccharomycopsis lipolytica". European Journal of Biochemistry. 128 (2–3): 489–94. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06991.x. PMID 6759120.

- ^ Jaklitsch WM, Kubicek CP (July 1990). "Homocitrate synthase from Penicillium chrysogenum. Localization, purification of the cytosolic isoenzyme, and sensitivity to lysine". The Biochemical Journal. 269 (1): 247–53. doi:10.1042/bj2690247. PMC 1131560. PMID 2115771.

- ^ Ye ZH, Bhattacharjee JK (December 1988). "Lysine biosynthesis pathway and biochemical blocks of lysine auxotrophs of Schizosaccharomyces pombe". Journal of Bacteriology. 170 (12): 5968–70. doi:10.1128/jb.170.12.5968-5970.1988. PMC 211717. PMID 3142867.

- ^ Kobashi N, Nishiyama M, Tanokura M (March 1999). "Aspartate kinase-independent lysine synthesis in an extremely thermophilic bacterium, Thermus thermophilus: lysine is synthesized via alpha-aminoadipic acid not via diaminopimelic acid". Journal of Bacteriology. 181 (6): 1713–8. doi:10.1128/JB.181.6.1713-1718.1999. PMC 93567. PMID 10074061.

- ^ Kosuge T, Hoshino T (1999). "The alpha-aminoadipate pathway for lysine biosynthesis is widely distributed among Thermus strains". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 88 (6): 672–5. doi:10.1016/S1389-1723(00)87099-1. PMID 16232683.

- ^ a b c d Nishida H, Nishiyama M, Kobashi N, Kosuge T, Hoshino T, Yamane H (December 1999). "A prokaryotic gene cluster involved in synthesis of lysine through the amino adipate pathway: a key to the evolution of amino acid biosynthesis". Genome Research. 9 (12): 1175–83. doi:10.1101/gr.9.12.1175. PMID 10613839.

- ^ a b c d Nishida H, Nishiyama M (September 2000). "What is characteristic of fungal lysine synthesis through the alpha-aminoadipate pathway?". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 51 (3): 299–302. Bibcode:2000JMolE..51..299N. doi:10.1007/s002390010091. PMID 11029074. S2CID 1265909.

- ^ Zabriskie TM, Jackson MD (February 2000). "Lysine biosynthesis and metabolism in fungi". Natural Product Reports. 17 (1): 85–97. doi:10.1039/a801345d. PMID 10714900.

- ^ a b Zhu X, Galili G (May 2004). "Lysine metabolism is concurrently regulated by synthesis and catabolism in both reproductive and vegetative tissues". Plant Physiology. 135 (1): 129–36. doi:10.1104/pp.103.037168. PMC 429340. PMID 15122025.

- ^ a b c d e Tomé D, Bos C (June 2007). "Lysine requirement through the human life cycle". The Journal of Nutrition. 137 (6 Suppl 2): 1642S–1645S. doi:10.1093/jn/137.6.1642S. PMID 17513440.

- ^ Blemings KP, Crenshaw TD, Swick RW, Benevenga NJ (August 1994). "Lysine-alpha-ketoglutarate reductase and saccharopine dehydrogenase are located only in the mitochondrial matrix in rat liver". The Journal of Nutrition. 124 (8): 1215–21. doi:10.1093/jn/124.8.1215. PMID 8064371.

- ^ Galili G, Tang G, Zhu X, Gakiere B (June 2001). "Lysine catabolism: a stress and development super-regulated metabolic pathway". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 4 (3): 261–6. doi:10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00170-9. PMID 11312138.

- ^ Arruda P, Kemper EL, Papes F, Leite A (August 2000). "Regulation of lysine catabolism in higher plants". Trends in Plant Science. 5 (8): 324–30. doi:10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01688-5. PMID 10908876.

- ^ Sacksteder KA, Biery BJ, Morrell JC, Goodman BK, Geisbrecht BV, Cox RP, Gould SJ, Geraghty MT (June 2000). "Identification of the alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase gene, which is defective in familial hyperlysinemia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (6): 1736–43. doi:10.1086/302919. PMC 1378037. PMID 10775527.

- ^ Zhu X, Tang G, Galili G (December 2002). "The activity of the Arabidopsis bifunctional lysine-ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine dehydrogenase enzyme of lysine catabolism is regulated by functional interaction between its two enzyme domains". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (51): 49655–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.m205466200. PMID 12393892.

- ^ a b c Kiyota E, Pena IA, Arruda P (November 2015). "The saccharopine pathway in seed development and stress response of maize". Plant, Cell & Environment. 38 (11): 2450–61. doi:10.1111/pce.12563. PMID 25929294.

- ^ Serrano GC, Rezende e Silva Figueira T, Kiyota E, Zanata N, Arruda P (March 2012). "Lysine degradation through the saccharopine pathway in bacteria: LKR and SDH in bacteria and its relationship to the plant and animal enzymes". FEBS Letters. 586 (6): 905–11. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.023. PMID 22449979. S2CID 32385212.

- ^ a b c Danhauser K, Sauer SW, Haack TB, Wieland T, Staufner C, Graf E, Zschocke J, Strom TM, Traub T, Okun JG, Meitinger T, Hoffmann GF, Prokisch H, Kölker S (December 2012). "DHTKD1 mutations cause 2-aminoadipic and 2-oxoadipic aciduria". American Journal of Human Genetics. 91 (6): 1082–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.006. PMC 3516599. PMID 23141293.

- ^ Sauer SW, Opp S, Hoffmann GF, Koeller DM, Okun JG, Kölker S (January 2011). "Therapeutic modulation of cerebral L-lysine metabolism in a mouse model for glutaric aciduria type I". Brain. 134 (Pt 1): 157–70. doi:10.1093/brain/awq269. PMID 20923787.

- ^ Goncalves RL, Bunik VI, Brand MD (February 2016). "Production of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide by the mitochondrial 2-oxoadipate dehydrogenase complex". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 91: 247–55. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.020. PMID 26708453.

- ^ Goh DL, Patel A, Thomas GH, Salomons GS, Schor DS, Jakobs C, Geraghty MT (July 2002). "Characterization of the human gene encoding alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase (AADAT)". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 76 (3): 172–80. doi:10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00037-9. PMID 12126930.

- ^ Härtel U, Eckel E, Koch J, Fuchs G, Linder D, Buckel W (1 February 1993). "Purification of glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas sp., an enzyme involved in the anaerobic degradation of benzoate". Archives of Microbiology. 159 (2): 174–81. doi:10.1007/bf00250279. PMID 8439237. S2CID 2262592.

- ^ Sauer SW (October 2007). "Biochemistry and bioenergetics of glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 30 (5): 673–80. doi:10.1007/s10545-007-0678-8. PMID 17879145. S2CID 20609879.

- ^ Nelson DL, Cox MM, Lehninger AL (2013). Lehninger principles of biochemistry (6th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-1-4641-0962-1. OCLC 824794893.

- ^ a b Galili G, Amir R (February 2013). "Fortifying plants with the essential amino acids lysine and methionine to improve nutritional quality". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 11 (2): 211–22. doi:10.1111/pbi.12025. PMID 23279001.

- ^ a b Wang G, Xu M, Wang W, Galili G (June 2017). "Fortifying Horticultural Crops with Essential Amino Acids: A Review". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (6): 1306. doi:10.3390/ijms18061306. PMC 5486127. PMID 28629176.

- ^ Angelovici R, Fait A, Fernie AR, Galili G (January 2011). "A seed high-lysine trait is negatively associated with the TCA cycle and slows down Arabidopsis seed germination". The New Phytologist. 189 (1): 148–59. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03478.x. PMID 20946418.

- ^ Edelman M, Colt M (2016). "Nutrient Value of Leaf vs. Seed". Frontiers in Chemistry. 4: 32. doi:10.3389/fchem.2016.00032. PMC 4954856. PMID 27493937.

- ^ Jiang SY, Ma A, Xie L, Ramachandran S (September 2016). "Improving protein content and quality by over-expressing artificially synthetic fusion proteins with high lysine and threonine constituent in rice plants". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 34427. Bibcode:2016NatSR...634427J. doi:10.1038/srep34427. PMC 5039639. PMID 27677708.

- ^ a b Shewry PR (November 2007). "Improving the protein content and composition of cereal grain". Journal of Cereal Science. 46 (3): 239–250. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2007.06.006.

- ^ Prasanna B, Vasal SK, Kassahun B, Singh NN (2001). "Quality protein maize". Current Science. 81 (10): 1308–1319. JSTOR 24105845.

- ^ a b Kircher M, Pfefferle W (April 2001). "The fermentative production of L-lysine as an animal feed additive". Chemosphere. 43 (1): 27–31. Bibcode:2001Chmsp..43...27K. doi:10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00320-9. PMID 11233822.

- ^ Junior L, Alberto L, Letti GV, Soccol CR, Junior L, Alberto L, Letti GV, Soccol CR (2016). "Development of an L-Lysine Enriched Bran for Animal Nutrition via Submerged Fermentation by Corynebacterium glutamicum using Agroindustrial Substrates". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 59. doi:10.1590/1678-4324-2016150519. ISSN 1516-8913.

- ^ University of Maryland Medical Center. "Lysine". Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Young VR, Pellett PL (1994). "Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (5 Suppl): 1203S–1212S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1203s. PMID 8172124. S2CID 35271281.

- ^ Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Macronutrients. p. 589. doi:10.17226/10490. ISBN 978-0-309-08525-0. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Dietary Supplement Database: Blend Information (DSBI)".

L-LYSINE HCL 10000820 80.03% lysine

- ^ a b Betts MJ, Russell RB (2003). Barnes MR, Gray IC (eds.). Bioinformatics for Geneticists. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 289–316. doi:10.1002/0470867302.ch14. ISBN 978-0-470-86730-3.

- ^ Blickling S, Renner C, Laber B, Pohlenz HD, Holak TA, Huber R (January 1997). "Reaction mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrodipicolinate synthase investigated by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy". Biochemistry. 36 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1021/bi962272d. PMID 8993314. S2CID 23072673.

- ^ Kumar S, Tsai CJ, Nussinov R (March 2000). "Factors enhancing protein thermostability". Protein Engineering. 13 (3): 179–91. doi:10.1093/protein/13.3.179. PMID 10775659.

- ^ Sokalingam S, Raghunathan G, Soundrarajan N, Lee SG (9 July 2012). "A study on the effect of surface lysine to arginine mutagenesis on protein stability and structure using green fluorescent protein". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e40410. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...740410S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040410. PMC 3392243. PMID 22792305.

- ^ a b Dambacher S, Hahn M, Schotta G (July 2010). "Epigenetic regulation of development by histone lysine methylation". Heredity. 105 (1): 24–37. doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.49. PMID 20442736.

- ^ Martin C, Zhang Y (November 2005). "The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 6 (11): 838–49. doi:10.1038/nrm1761. PMID 16261189. S2CID 31300025.

- ^ Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR (November 2012). "Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact". Molecular Cell. 48 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006. PMC 3861058. PMID 23200123.

- ^ Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M (August 2009). "Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions". Science. 325 (5942): 834–40. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..834C. doi:10.1126/science.1175371. PMID 19608861. S2CID 206520776.

- ^ Shiio Y, Eisenman RN (November 2003). "Histone sumoylation is associated with transcriptional repression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (23): 13225–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.1735528100. PMC 263760. PMID 14578449.

- ^ Wang H, Wang L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Vidal M, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y (October 2004). "Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing". Nature. 431 (7010): 873–8. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..873W. doi:10.1038/nature02985. hdl:10261/73732. PMID 15386022. S2CID 4344378.

- ^ a b Shoulders MD, Raines RT (2009). "Collagen structure and stability". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 78: 929–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. PMC 2846778. PMID 19344236.

- ^ a b Civitelli R, Villareal DT, Agnusdei D, Nardi P, Avioli LV, Gennari C (1992). "Dietary L-lysine and calcium metabolism in humans". Nutrition. 8 (6): 400–5. PMID 1486246.

- ^ a b c d Vaz FM, Wanders RJ (February 2002). "Carnitine biosynthesis in mammals". The Biochemical Journal. 361 (Pt 3): 417–29. doi:10.1042/bj3610417. PMC 1222323. PMID 11802770.

- ^ Yamauchi M, Sricholpech M (25 May 2012). "Lysine post-translational modifications of collagen". Essays in Biochemistry. 52: 113–33. doi:10.1042/bse0520113. PMC 3499978. PMID 22708567.

- ^ Vollmer W, Blanot D, de Pedro MA (March 2008). "Peptidoglycan structure and architecture". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 32 (2): 149–67. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. PMID 18194336.

- ^ Curtiss R (May 1978). "Biological containment and cloning vector transmissibility". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 137 (5): 668–75. doi:10.1093/infdis/137.5.668. PMID 351084.

- ^ a b Flanagan JL, Simmons PA, Vehige J, Willcox MD, Garrett Q (April 2010). "Role of carnitine in disease". Nutrition & Metabolism. 7: 30. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-30. PMC 2861661. PMID 20398344.

- ^ a b Chromiak JA, Antonio J (2002). "Use of amino acids as growth hormone-releasing agents by athletes". Nutrition. 18 (7–8): 657–61. doi:10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00807-9. PMID 12093449.

- ^ Corpas E, Blackman MR, Roberson R, Scholfield D, Harman SM (July 1993). "Oral arginine-lysine does not increase growth hormone or insulin-like growth factor-I in old men". Journal of Gerontology. 48 (4): M128–33. doi:10.1093/geronj/48.4.M128. PMID 8315224.

- ^ Gaby AR (2006). "Natural remedies for Herpes simplex". Altern Med Rev. 11 (2): 93–101. PMID 16813459.

- ^ Tomblin FA, Lucas KH (2001). "Lysine for management of herpes labialis". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 58 (4): 298–300, 304. doi:10.1093/ajhp/58.4.298. PMID 11225166.

- ^ Chi CC, Wang SH, Delamere FM, Wojnarowska F, Peters MC, Kanjirath PP (7 August 2015). "Interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD010095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010095.pub2. PMC 6461191. PMID 26252373.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to L-lysine and immune defence against herpes virus (ID 453), maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 454, 4669), increase in appetite leading to an increase in energ". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2063. 2011. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2063. ISSN 1831-4732.

- ^ Pinnell SR, Krane SM, Kenzora JE, Glimcher MJ (May 1972). "A heritable disorder of connective tissue. Hydroxylysine-deficient collagen disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 286 (19): 1013–20. doi:10.1056/NEJM197205112861901. PMID 5016372.

- ^ Rudman D, Sewell CW, Ansley JD (September 1977). "Deficiency of carnitine in cachectic cirrhotic patients". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 60 (3): 716–23. doi:10.1172/jci108824. PMC 372417. PMID 893675.

- ^ a b Rushton DH (July 2002). "Nutritional factors and hair loss". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 27 (5): 396–404. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01076.x. PMID 12190640. S2CID 39327815.

- ^ Emery PW (October 2005). "Metabolic changes in malnutrition". Eye. 19 (10): 1029–34. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6701959. PMID 16304580.

- ^ Ghosh S, Smriga M, Vuvor F, Suri D, Mohammed H, Armah SM, Scrimshaw NS (October 2010). "Effect of lysine supplementation on health and morbidity in subjects belonging to poor peri-urban households in Accra, Ghana". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 92 (4): 928–39. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28834. PMID 20720257.

- ^ a b Houten SM, Te Brinke H, Denis S, Ruiter JP, Knegt AC, de Klerk JB, Augoustides-Savvopoulou P, Häberle J, Baumgartner MR, Coşkun T, Zschocke J, Sass JO, Poll-The BT, Wanders RJ, Duran M (April 2013). "Genetic basis of hyperlysinemia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 8: 57. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-57. PMC 3626681. PMID 23570448.

- ^ Hoffmann GF, Kölker S (2016). Inborn Metabolic Diseases. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 333–348. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-49771-5_22. ISBN 978-3-662-49769-2.

- ^ Dancis J, Hutzler J, Ampola MG, Shih VE, van Gelderen HH, Kirby LT, Woody NC (May 1983). "The prognosis of hyperlysinemia: an interim report". American Journal of Human Genetics. 35 (3): 438–42. PMC 1685659. PMID 6407303.

- ^ Mills PB, Struys E, Jakobs C, Plecko B, Baxter P, Baumgartner M, Willemsen MA, Omran H, Tacke U, Uhlenberg B, Weschke B, Clayton PT (March 2006). "Mutations in antiquitin in individuals with pyridoxine-dependent seizures". Nature Medicine. 12 (3): 307–9. doi:10.1038/nm1366. PMID 16491085. S2CID 27940375.

- ^ Mills PB, Footitt EJ, Mills KA, Tuschl K, Aylett S, Varadkar S, Hemingway C, Marlow N, Rennie J, Baxter P, Dulac O, Nabbout R, Craigen WJ, Schmitt B, Feillet F, Christensen E, De Lonlay P, Pike MG, Hughes MI, Struys EA, Jakobs C, Zuberi SM, Clayton PT (July 2010). "Genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (ALDH7A1 deficiency)". Brain. 133 (Pt 7): 2148–59. doi:10.1093/brain/awq143. PMC 2892945. PMID 20554659.

- ^ Hagen J, te Brinke H, Wanders RJ, Knegt AC, Oussoren E, Hoogeboom AJ, Ruijter GJ, Becker D, Schwab KO, Franke I, Duran M, Waterham HR, Sass JO, Houten SM (September 2015). "Genetic basis of alpha-aminoadipic and alpha-ketoadipic aciduria". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 38 (5): 873–9. doi:10.1007/s10545-015-9841-9. PMID 25860818. S2CID 20379124.

- ^ Hedlund GL, Longo N, Pasquali M (May 2006). "Glutaric acidemia type 1". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 142C (2): 86–94. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30088. PMC 2556991. PMID 16602100.

- ^ "Hyperlysinuria Define Hyperlysinuria at Dictionary.com".

- ^ a b Walter, John; John Fernandes; Jean-Marie Saudubray; Georges van den Berghe (2006). Inborn Metabolic Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. Berlin: Springer. p. 296. ISBN 978-3-540-28783-4.

- ^ a b "Norwegian granted for improving lysine production process". All About Feed. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012.

- ^ Toride Y (2004). "Lysine and other amino acids for feed: production and contribution to protein utilization in animal feeding". Protein sources for the animal feed industry; FAO Expert Consultation and Workshop on Protein Sources for the Animal Feed Industry; Bangkok, 29 April - 3 May 2002. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-105012-5.

- ^ Abelson PH (March 1999). "A potential phosphate crisis". Science. 283 (5410): 2015. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.2015A. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2015. PMID 10206902. S2CID 28106949.

- ^ Coyne JA (10 October 1999). "The Truth Is Way Out There". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ Wu G (May 2009). "Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition". Amino Acids. 37 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0. PMID 19301095. S2CID 1870305.

- ^ Connor JM (2008). Global Price Fixing (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-78669-6.

- ^ Eichenwald K (2000). The Informant: a true story. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-0326-4.