The 50 Greatest Horror Movies of the 21st Century

Sort by:

Showing 50 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

Ever since audiences ran screaming from the premiere of Auguste and Louis Lumière’s 1895 short black-and-white silent documentary Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, the histories of filmgoing and horror have been inextricably intertwined. Through the decades—and subsequent crazes for color and sound, stereoscopy and anamorphosis—since that train threatened to barrel into the front row, there’s never been a time when audiences didn’t clamor for the palpating fingers of fear. Horror films remain perennially popular, despite periodic (and always exaggerated) rumors of their demise, even in the face of steadily declining ticket sales and desperately shifting models of distribution.

Into the new millennium, horror films have retained their power to shock and outrage by continuing to plumb our deepest primordial terrors, to incarnate our sickest, most socially unpalatable fantasies. They are, in what amounts to a particularly delicious irony, a “safe space” in which we can explore these otherwise unfathomable facets of our true selves, while yet consoling ourselves with the knowledge that “it’s only a movie.”

At the same time, the genre manages to find fresh and powerful metaphors for where we’re at as a society and how we endure fractious, fearful times. For every eviscerated remake or toothless throwback, there’s a startlingly fresh take on the genre’s most time-honored tropes; for every milquetoast PG-13 compromise, there’s a ferocious take-no-prisoners attempt to push the envelope on what we can honestly say about ourselves. Budd Wilkins

Published by Slant Magazine, October 2018

Into the new millennium, horror films have retained their power to shock and outrage by continuing to plumb our deepest primordial terrors, to incarnate our sickest, most socially unpalatable fantasies. They are, in what amounts to a particularly delicious irony, a “safe space” in which we can explore these otherwise unfathomable facets of our true selves, while yet consoling ourselves with the knowledge that “it’s only a movie.”

At the same time, the genre manages to find fresh and powerful metaphors for where we’re at as a society and how we endure fractious, fearful times. For every eviscerated remake or toothless throwback, there’s a startlingly fresh take on the genre’s most time-honored tropes; for every milquetoast PG-13 compromise, there’s a ferocious take-no-prisoners attempt to push the envelope on what we can honestly say about ourselves. Budd Wilkins

Published by Slant Magazine, October 2018

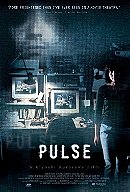

Empowered by the rise of the internet culture, spirits draw humans away from one another, entombing them in a realm of their own private obsessions. Does this even count as a metaphor anymore? Until the recent The Bling Ring, Pulse is the closest a film has come to fully capturing the paradoxical and deceptively empowering trap of online societies that allow you to indulge an illusion of socialization alone in the privacy of your own home. Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s ferocious act of despairing protest is also one of cinema’s most unnerving and suggestive ghost stories. Bowen

Under the Skin (2013)

Under the Skin‘s extraterrestrial seductress, Laura (Scarlett Johansson), shrinks in stature as the film progresses, from an indomitable, inviolable man-eating ghoul to an increasingly fragile woman suffering from the psychic trauma wreaked by her own weaponized sexuality. It’s a heartbreaking process to witness, one that flips a sleek, mysterious sci-fi thriller into a singular melodrama focused on the unlikeliest of protagonists. Establishing an atmosphere in which each new intrusion of feeling delivers another blow to the character’s once-steely exterior, director Jonathan Glazer spins out a maelstrom of dread as Laura simultaneously contracts and expands, adapting to the frailty of her assumed human form. Cataldo

Trouble Every Day (2001)

While Trouble Every Day operates, superbly, as a biological-themed horror film, it would cheapen Claire Denis’s achievement to say that she merely literalizes the violent implications of sex, even when manifested as traditional “romantic” lovemaking. The filmmaker expounds on the notion of sex-as-violence with an unnerving clarity that appears to explain why acts of theoretical love and brutality assume such disconcertingly similar outward appearances, as both involve attempts to foster illusions of control where there aren’t any. Theoretically, sex involves a search for communion, intimacy, whereas violence is often an expression of dominance, and Denis shows that intimacy and dominance are similarly impossible concepts to realize with any degree of permanency, if we’re to be truthful with ourselves. Bowen

Inland Empire (2006)

Radical even for director David Lynch, Inland Empire suggests the potential emergence of a new medium that remains unfulfilled, a medium that fuses the emotional and narrative containment of cinema with the elusive impermanency of the Internet. The entire history and future of cinema seems to flow intangibly through this film, which suggests, at times, an epic expansion of the visionary imagery from A Page of Madness. Laura Dern’s fearless performance embodies the loss of someone who’s torn between forces that are suggestive of bottomless chaos. It’s one of the most truly terrifying films ever made, but is it a horror movie? It’s every movie. Bowen

Wolf Creek (2005)

A blistering jolt of existential terror that doesn’t come with the noxious sexual baggage that typically dooms its horror ilk, Wolf Creek begins with the stunning image of sunset-tinted waves crashing onto the sands of an Australian beachfront. For a split second, this expressionistic shot resembles a volcano blowing its top, and the realization that it’s something entirely more mundane exemplifies the unsettling tenor of the film’s casual shocks. Like The Hitcher and Near Dark before it, Wolf Creek is propelled by a lyrical sense of doom, expressing a gripping vision of characters struggling and resisting to be made out by a terror that seems at once terrestrial and alien. Gonzalez

Antichrist (2009)

Lars von Trier’s two-hander psychodrama Antichrist draws heavily from a rich tradition of “Nordic horror,” stretching back to silent-era groundbreakers like Häxan and Vampyr (and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s later Day of Wrath), in particular their interrogation of moral strictures and assumptions of normalcy. In the wake of their son’s death, He (Willem Dafoe) and She (Charlotte Gainsbourg) follow a course of radical psychotherapy, retreating to their wilderness redoubt, Eden, where they act out (and on) their mutual resentment and recrimination, culminating in switchback brutal attacks and His and Her genital mutilations. Conventional wisdom has it that von Trier’s a faux provocateur, but that misses his theme and variation engagement with genre and symbolism throughout, rendering Antichrist one of the most bracingly personal, as well as national cinema-indebted, films to come along in a while. It’s heartening to see that real provocation still has a place in the forum (let’s not say “marketplace”) of international cinema. Bill Weber

Halloween II (2009)

An alternate title for Rob Zombie’s Halloween II could be Sympathy for the Devil. If Michael Myers was almost a phantom presence in John Carpenter’s Halloween, here he’s unmistakably and chillingly real. Throughout, Michael suggests a nomad single-mindedly driven by a desire to obliterate every connection to his namesake, and the scope of his brutality suggests a clogged id’s flushing out. In this almost Lynchian freak-out, whose sense of loss comes to the fore in a scene every bit as heartbreaking as its violence is discomfiting in its graphic nature, Zombie’s prismatic aesthetic is cannily rhymed with Michael’s almost totemic mood swings, every obscenely prolonged kill scene a stunning reflection on an iconic movie monster’s psychological agony. Gonzalez

JxSxPx's rating:

Not unlike Matt Reeves’s American remake, Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In is, in its color scheme and emotional tenor, something almost unbearably blue. When Oskar (Kåre Hedebrant), a 12-year-old outcast perpetually bullied at school, meets Eli (Lina Leandersson), the mysterious new girl at his apartment complex, one child’s painful coming of age is conflated with another’s insatiable bloodlust. The film treats adolescence, even a vampire’s arrested own, as a prolonged horror—life’s most vicious and unforgiving set piece. This study of human loneliness and the prickly crawlspace between adolescence and adulthood is also an unexpectedly poignant queering of the horror genre. Don’t avert your eyes from Alfredson’s gorgeously, meaningfully aestheticized vision, though you may want to cover your neck. Gonzalez

JxSxPx's rating:

Guillermo del Toro’s films are rabid commentaries on the suspension of time, often told through the point of view of children. A bomb is dropped from the skies above an isolated Spanish orphanage, which leaves a boy bleeding to death in its mysterious, inexplosive wake. His corpse is then tied and shoved into the orphanage’s basement pool, and when a young boy, Carlos (Fernando Tielve), arrives at the ghostly facility some time later, he seemingly signals the arrival of Franco himself. A rich political allegory disguised as an art-house spooker, The Devil’s Backbone hauntingly ruminates on the decay of country whose living are so stuck in past as to seem like ghosts. But there’s hope in brotherhood, and in negotiating the ghostly Santi’s past and bandying together against the cruel Jacinto (Eduardo Noriega), the film’s children ensure their survival and that of their homeland. Gonzalez

JxSxPx's rating:

Martyrs (2008)

Writer-director Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs leaves you with the scopophilic equivalent of shell shock. The gauntlet that his film’s heroine, a “final girl” who’s abducted and tortured by a religious cult straight out of a Clive Barker novel, is forced to endure is considerable. Which is like saying that King Kong is big, Vincent Price’s performances are campy, and blood is red. Laugier’s film is grueling because there’s no real way to easily get off on images of simulated violence. The film’s soul-crushing finale makes it impossible to feel good about anything Laugier has depicted. In it, Laugier suggests that there’s no way to escape from the pain of the exclusively physical reality of his film. You don’t watch Laugier’s harrowing feel-bad masterpiece—rather, you’re held in its thrall. Abandon hope all ye who watch here. Abrams

Raw (2016)

As in Ginger Snaps, which Raw thematically recalls, the protagonist’s supernatural awakening is linked predominantly to sex. At the start of the film, Justine (Garance Marillier) is a virgin who’s poked and prodded relentlessly by her classmates until she evolves only to be rebuffed for being too interested in sex—a no-win hypocrisy faced by many women. High-pressure taunts casually and constantly hang in the air, such as Alexia’s (Ella Rumpf) insistence that “beauty is pain” and a song that urges a woman to be “a whore with decorum.” In this film, a bikini wax can almost get one killed, and a drunken quest to get laid can, for a female, lead to all-too-typical humiliation and ostracizing. Throughout Raw, director Julia Ducournau exhibits a clinical pitilessness that’s reminiscent of the body-horror films of David Cronenberg, often framing scenes in symmetrical tableaus that inform the various cruelties and couplings with an impersonality that’s ironically relieved by the grotesque intimacy of the violence. We’re witnessing conditioning at work, in which Justine is inoculated into conventional adulthood, learning the self-shame that comes with it as a matter of insidiously self-censorious control. By the film’s end, Ducournau has hauntingly outlined only a few possibilities for Justine: that she’ll get with the program and regulate her hunger properly, or be killed or institutionalized. Bowen

The Host (2006)

Scott Wilson’s deliciously hammy presence as the American captain in the opening scene indicates that Bong Joon-ho’s The Host is, in the broadest sense, a politically charged diatribe against both American and Korean political cover-up machinations of misinformation. But that aspect is rather bland in comparison to what else the film has to offer. For, like any great monster movie, this isn’t a film strictly about a monster—or, for that matter, the monstrous countries that spawned it—but about something else: the significance of sustenance. That is, The Host is a film chiefly concerned with food: who, how, and where we get it from, what it is we choose to eat, and why we eat it at all. Ryland Walker Knight

JxSxPx's rating:

Get Out‘s central conceit, about a Stepford Wives-ish plot by blithely entitled suburban whites to colonize black people’s bodies, is a trenchant metaphor for white supremacy. The timing, character development, and gift for social satire that writer-director Jordan Peele honed as a sketch comedian all translate effortlessly to horror, allowing the first-time filmmaker to entrance his audience as deftly as Catherine Keener’s Missy mesmerizes Daniel Kaluuya’s Chris with that tapping teaspoon. The Sunken Place where Missy maroons Chris is the film’s most indelible image, a stomach-churning representation of how it feels to be stripped of your autonomy and personhood by a dominant culture that remains cruelly blind and deaf to your plight. In a world where almost no one is what they initially appear to be, Get Out anatomizes the evil lurking in the relatively benign-seeming prejudice that plays out as fetishization or envy, a form of racism that doesn’t see itself as racist at all. Elise Nakhnikian

JxSxPx's rating:

I Saw the Devil (2010)

Kim Jee-woon’s ultra-stylish, gleefully brutalist I Saw the Devil is at bottom a Grand Guignol reduction-to-absurdity of Nietzsche’s maxim that one who battles monsters must beware lest he become one himself—though how seriously the film takes its own philosophical underpinnings is anybody’s guess. Kim seemingly relishes the escalating tango of retribution between psychopathic bus driver Jang Kyung-chul (Choi Min-sik) and bereaved federal agent Kim Soo-hyun (Lee Byung-hun), getting his directorial rocks off on every sadistic set piece with the unbridled abandon of Dario Argento at his peak. The nihilistic, nobody-wins ending ultimately aligns I Saw the Devil with a film that otherwise seems like its diametric opposite: Wes Craven’s grungy, lo-fi Bergman piss take The Last House on the Left. Wilkins

The Devil's Rejects (2005)

If House of 1000 Corpses successfully transposed the grotesqueries evoked by Rob Zombie’s music onto film, then The Devil’s Rejects cemented his status as a filmmaker worth noticing. Zombie’s sophomore effort, ungodly violent and gruesome as it is, would be nearly unbearable to watch were it not so wonderfully aestheticized. His most noticeable trait as a stylist is, unsurprisingly, a knack for selecting the perfect songs to both match and offset the morbid goings-on of his film, but there’s more at work here than mere artifice: Zombie infuses an unexpected somberness where his debut tended toward camp. His sideshow-esque cast of characters, while far from sympathetic, have evolved into genuinely fleshed-out beings whose unexpected pathos only intensifies the terror they evoke. The rejects’ long string of satanic ritual murders make for a carnivalesque experience far more viscerally stimulating—and strangely watchable—than it seems to have any right to be. Nordine

The House of the Devil (2009)

Though The House of the Devil is so steeped in nostalgia for the genre films of yore that it seems to belong far more to the 1980s than to the present day, it nevertheless carved a perfect niche for itself in late-aughts cinema. Ti West deals in nail-biting suspense and dread, making him a welcome outlier among his more gore-obsessed contemporaries: Each time the filmmaker punctuates one of The House of the Devil‘s long periods of placidity and unease via an abrupt act of violence, the moment feels earned, even necessary, rather than tacked on. It’s a film that both relies on and rewards the viewer’s imagination to fill in the blanks of its slow-going narrative, a refreshing change of pace from the mindless horror fodder it surpasses with such ease and gravitas. Michael Nordine

Revenge (2017)

Like S. Craig Zahler’s Brawl in Cell Block 99, Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge is so extravagantly violent and hopeless that it boasts a weird integrity. These thrillers suggest that there’s little room for morals in cinema, which is a playpen of fantasies that are too often sanctified by platitudes. Take Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here, an occasionally quite visceral riff on Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Paul Schrader’s Hardcore that’s terrified of the possibility that it may be a genre film rather than Something Important. Revenge clears the air of the hedging and insecurity that are common of prestige cinema and of pop culture at large, tapping the prurient desires that drive most audiences to see genre films in the first place. Bowen

Visitor Q acts as a correction to the relentless popularity of reality TV, a phenomenon that invites us to vicariously feast on human misery as distraction from our own daily indignities. The story follows a family as they casually film one another indulging in incest and necrophilia as well as a long list of other similarly taboo activities, and Takeshi Miike stages each escalating atrocity with a flip, tongue-in-cheek, and sometimes nearly slapstick manner that’s authentically horrifying. Yet, the filmmaker, as Audition made clear, is a moralist deep down, and the brilliant, surreal Visitor Q—so powerful and disgusting that many will probably find it unwatchable—is the ultimate middle finger to media-sponsored narcissism. Bowen

The Strangers (2008)

The Strangers is practically an abstraction, an old-school spooker spun from the blood splatter on a wall, a nearby record player scratching an oldie, a CB radio in the garage, a creaky swing set in the backyard. Bryan Bertino is beholden to genre quota, skidding the relationship of pretty young couple Kristen and James (Liv Tyler and Scott Speedman) before subjecting them to an after-dark home invasion. But he offers no profound rationale for why she refuses his marriage proposal; like the shadowy stranger that comes knocking at their door (eerily asking, “Is Tamara home?”), it’s something that just happens. Plying an old-school artistry that begins with a creepy montage of bumblefuck houses and holds up almost without fail until the strangers offer a creepy non-justification for their transgressions, analog-man Bertino teases with the unknown until he’s left no pimple ungoosed. Gonzalez

A Quiet Place (2018)

A Quiet Place, like John Carpenter’s The Thing before it, contributes a strikingly original monster to the genre of horror films focused exclusively on surviving an invasive threat. The big bad at the center of John Krasinski’s film is a species of flesh-eating hellion that happens to be blind, and thus its potential prey can successfully evade capture by being silent at all times. When the bonds between the Abbotts are tested by the external threat of the alien invaders, the viscerally physical ways in which they protect each other from harm are powerful, and it becomes clear that these characters have had to learn different and perhaps more subtle methods of communication due to the circumstances in which they’ve found themselves. The pleasure of the film is in Krasinski’s commitment to imagining the resourceful ways in which a family like this might survive in this kind of world, then bearing witness to the filmmaker’s skillfully constructed methods of putting them to the ultimate test, relentlessly breaking down all of the walls the family has erected to keep the monsters out. Richard Scott Larson

Session 9 (2001)

As in real estate, the three most important factors in Brad Anderson’s brooding Session 9 are: location, location, location. The filmmakers have hit upon something special with the Danvers State Mental Hospital, whose sprawling Victorian edifice looms large over the narrative: A motley crew of asbestos-removal workers, led by matrimonially challenged Gordon (Peter Mullan), run afoul of a baleful, possibly supernatural, influence within its decaying walls. Anderson uses to brilliant effect a series of archived audio recordings—leading up to the titular “breakthrough” session—that document a disturbing case of split personality. While the film doesn’t entirely stick its murderous finale, no one who hears those scarifying final lines of dialogue will soon forget them. Wilkins

The Wailing (2016)

Na Hong-jin’s The Wailing is a work of thriller maximal-ism, thriving on genre crosspollination and tonal hyperbole, particularly a destabilizing contrast of broad comedy with ultraviolent portentousness. Na is an atmospheric reveler who sets the film’s narrative traps so gradually that we come to accept his increasingly insane plot as inevitable. He’s at once fashioned a hangout movie, luxuriating in the eccentricities of the story’s village locals, and a relentlessly precise and momentous supernatural thriller, with two ingenious climaxes that each juxtapose dueling interrogations, revealing men to exhibit little grasp of the world that engulfs them. Bowen

Mandy (2018)

Mandy‘s smorgasbord of indulgences is held together by Nicolas Cage, who gives one of the best performances of his career. Director Panos Cosmatos understands Cage as well as any director ever has, fashioning a series of moments that allow the actor to rhythmically blow off his top, exorcising Red’s rage and longing as well as, presumably, his own. In the film’s best scene, Red storms into the bathroom of his cabin and lets out a primal roar, while chugging a bottle of liquor that was stashed under the sink. Cage gives this scene a disquieting sense of relief, investing huge emotional notes with a lingering undercurrent that cuts to the heart of the film itself. Happiness is dangerously foreign to people like Red, while obliteration is at least familiar. Mandy is a profoundly violent and weirdly moving poem of male alienation. Bowen

Bug, an intense little chamber play of blossoming madness, allowed William Friedkin to put his characteristic screws to both his characters and his audience while nearly achieving a poignancy that only heightens the horror. Your enjoyment of the film may depend on whether or not you buy how quickly Ashley Judd succumbs to paranoia and insanity. I didn’t buy it, but the film’s relentlessness overcomes the occasionally stagy absurdity. In one of his first key roles, Michael Shannon looks a little like Anthony Michael Hall at his most hungover, but his presence and surprisingly soft voice throws you off balance, and Friedkin masterfully exploits that emotional uncertainty, paving the way for an ending that’s abrupt, unforgiving, and the perfect capper for a very over the top last third. Bug is both thriller and horror film, as well as the most perverse of romances—a heightened, demented parable of losing yourself to someone. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

The Guest (2014)

The Guest is carried by an intense and surprising mood of erotic melancholia. Adam Wingard leans real heavy on 1980s—or 1980s-sounding—music in the grandly, outwardly wounded key of Joy Division, and he accompanies the music with visual sequences that sometimes appear to stop in their tracks for the sake of absorbing the soundtrack. The film is a nostalgia act for sure, particularly for The Hitcher, but it injects that nostalgia with something hard, sad, and contemporary, or, perhaps more accurately, it reveals that our hang-ups—disenfranchisement, rootlessness, war-mongering, hypocritical evasion—haven’t changed all that much since the 1980s, or ever. Bowen

Inside (2007)

Filmmakers Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury announce their disregard for all notions of restraint with their opening image of a severe car accident as seen and experienced by an unborn child. One moment the child is soothed by his mother’s loving, if alarming, words, the next he’s throttled, blood rising and floating from the inside. The film is driven by this accident, and what follows is the most potent exploitation of unyielding, inexplicable violation outside of Takashi Miike’s Audition. The violence is ghastly and apt thematically: Tides of blood flow and spurt, hauntingly confirming a terrified young woman’s most forbidden nightmares. Bowen

Oculus (2014)

Oculus begins in dreams before freely hopscotching between Kaylie (Karen Gillan) and Tim’s (Brenton Thwaites) present-day sleuthing and the horrors that, 11 long years ago, sent her to foster care and him to a mental institution. Through a mini-triumph of montage, what begins as run-of-the-mill backstory vomit is thrillingly repackaged as an almost-Lynchian duet between warring states of consciousness. The story’s antique wall mirror, as it tightens its grip on the brother and sister, forces them to waltz alongside their younger selves during their parents’ last days, and subsequently the depth of the siblings’ fraught relationship to their shared past is put into poignant focus. Throughout, Mike Flanagan’s keying of his formalist frights to his characters’ subjectivities makes Oculus both a scarier and wittier haunted-house attraction than James Wan’s The Conjuring. Gonzalez

Robert Eggers does an admirable job of synchronizing The Witch‘s paranormal and domestic spheres, setting up a vice-grip scenario in which Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) has no possibility of escape. Her family’s restrictive religious practices are as domineering as the forlorn, featureless landscape which surrounds her, and this atmosphere only grows more stifling as the family pins blame on the girl for their mounting misfortunes. Positioning itself among a specific vein of highbrow phantasmagoric spiritualism, the film owes a serious debt to the unsettling ambiance of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror, Roman Polanski’s politically tinged psychological thrillers, and Ken Russell’s gonzo period pieces. But by allowing the monster to win, the film overcomes the sense of familiarity, as its reworking of a tired horror trope into a transformed feminist symbol stands out as an impressive act of genre revisionism. Jesse Cataldo

JxSxPx's rating:

The Lords of Salem (2013)

Crones as a manifestation of the internal ugliness we imagine of ourselves, while at the mercy of our blackest self-loathing, aren’t new. David Lynch has practically trademarked this kind of symbology in Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive, but Rob Zombie makes it his own, and he appears to be liberated by the challenge of largely reining in his wildly in-your-face aesthetic for the sake of following the lower-key tropes of the satanic-possession film. There’s a sense of contained restless energy in The Lords of Salem that’s introduced by Zombie’s unexpectedly deliberate camera movements and exasperated by the film’s flamboyant sense of chaotically cluttered architecture. With their busy, ugly wallpaper and stifling over-abundance of bric-a-brac, the rooms in this film often appear to be on the verge of swallowing poor Heidi Hawthorne (Sheri Moon-Zombie) alive. And, of course, they are. Bowen

Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Edgar Wright often concedes in his work that life is complicated and exhausting and basically just hard; the stuff we deal with every day, from relationships to familial responsibility to even just getting up for work in the morning, makes fending off zombies or cultists or straightforward baddies of any kind seem preferable. In the short-lived Channel 4 series Spaced, the struggle of two twentysomething creatives to claw their way out of dead-end minimum-wage jobs and see their loftier professional ambitions realized was tempered by fleeting retreats into pop-culture daydreams, where reality might look like Murder, She Wrote one moment and Resident Evil 2 the next. Shaun of the Dead took this device a step further: When a breakup violently disrupts the complacent man-child bubble of its hero, zombies arrive to violently disrupt the whole world along with it, reframing one man’s personal efforts to grow and learn the value of responsibility as a more literal question of life and death. Marsh

Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza give the enervated “found footage” genre a fresh infusion of creditability by splicing together strands of the ungovernable viral epidemic from 28 Days Later and The Evil Dead franchise’s fixation on sudden demonic conversion. An innocuous documentary on firefighters leads reporter Angela Vidal (Manuela Velasco) to an apartment building whose residents are quickly succumbing to some kind of plague. With its lean-and-mean 75-minute running time, [REC] unreels almost in real time, giving viewers precious little breathing room between increasingly ferocious attacks. As the survivors fight their way toward the penthouse, surely there’s some diabolical revelation at hand. What’s more, the film’s final image of a woman dragged off into all-consuming darkness has been endlessly imitated ever since. Wilkins

Drag Me to Hell (2009)

Many horror films from the 2000s are so eager to splatter and slice their way into our hearts that they end up covering their canvases in bloody clichés. Not so with Sam Raimi’s masterfully paced throwback, which is smart enough to withhold its more disturbing visceral elements until the very last moment. This directorial restraint allows the perfectly calibrated sound design and dread-inducing mise-en-scène to drive the viewer mad with anticipation. Anchored by Allison Lohman’s brilliant performance as a loan officer fated for Hades’s gallows, Drag Me to Hell is as much about greed as it is culpability, or more specifically our arrogant attempts to cover up sin even when the devil herself is staring us down. Glenn Heath Jr.

Demon (2015)

In Demon, director Marcin Wrona captures the airy, ineffable wrongness that drives a classic tale of the supernatural, which is typically occupied with the slight perversion of the banal. The tracking shots across the water, as Piotr (Itay Tiran) rides the ferry to a largely deserted Polish village, where the buildings are in disrepair and the roads are empty, are frightening because water is often used in this sort of horror fiction as a symbol of a vast, submerged dimension from which something is waiting to spring. This impression is heightened by images that soon follow of a rock quarry near the construction site overseen by Zaneta’s (Agnieszka Zulewska) father, which are rendered with an unsettlingly explicit sense of simultaneous verticality and horizontality. The audience is meant to sense, without a shred of exposition, that something primordial is being disrupted. Bowen

A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) (2003)

Writer-director Kim Jee-woon burst onto the K-horror field with this fractured retelling of a traditional Korean folktale. Siblings Su-mi (Im Soo-jung) and Su-yeon (Moon Geun-young) chafe under the tyrannous yoke of their aloof stepmother (Yum Jung-ah). Or do they? Because A Tale of Two Sisters is nothing if not unclear: Kim calculatingly blurs the boundaries between past and present, dream and reality, bombarding viewers with a kaleidoscopic blur of spectral apparitions and sudden violence that’s likely to leave viewers as terminally confused as young Su-mi. Mining the same vein of menstrual horror as the far more streamlined Carrie, Kim’s film doubles down on De Palma, cheekily suggesting its various haunted recesses—a linen closet, the dank space beneath the kitchen sink—as metaphorical vagina substitutes. Wilkins

JxSxPx's rating:

Sion Sono kicks things off with one of the great openers in recent horror cinema: Holding hands and chanting “a one and a two,” 50 uniformed Japanese high school girls throw themselves under a subway train, drenching bystanders in gouts and gallons of gore. Investigations into the ensuing outbreak of teenage suicide pacts, headed by Detective Kuroda (Ryo Ishibashi), leads to a tween-idol girl group disseminating hidden messages that exhort listeners to promptly snuff it, concealed in the media blitzkrieg surrounding their ear-candy megahit “Mail Me.” Boasting plenty of splatter for the fanboys (much of it blatantly artificial CGI), Suicide Club at times deepens into an existential inquiry, even if it raises more questions about social media manipulation and interpersonal disconnect than it can hope to answer. An outrageous finale takes its audience behind the music, and through the looking glass, into a harsh realm filled with gerbils, raincoat-clad tykes, and new uses for woodworking tools. Wilkins

As rabble-rousing talk radio host Grant Mazzy, Stephen McHattie has a voice like a baritone snake, equal parts silky and sinister, and it’s very pointedly the main attraction of Bruce McDonald’s Pontypool. When his A.M. gig reporting school closings and interviewing clownish local theater troupes is interrupted by reports of unruly mobs tearing people to shreds with their mouths, he and the radio station’s producer and technician must sense of the apparent mayhem brewing outside, the cause of which eventually turns out to be the spoken word itself. Talk Radio by way of George A. Romero, the film implies that terms of endearment, baby gibberish, and military-related talk—all of which seem to be particularly contagious—have been so misused as to have dangerously lost all meaning. Schager

Matt Reeves’s amplification of Let the Right One In‘s study of human loneliness and the prickly crawlspace between adolescence and adulthood isn’t even the filmmaker’s greatest coup; it’s his rooting of the story in March 1983, in a bleak region of New Mexico where no one moves to, only runs away from. Reeves, who wasn’t too much older than Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) in that year, prominently foregrounds a televised speech Reagan gave around that time (his budgetary-obsessed Star Wars one, no doubt), so that Let the Right One In becomes impossible to read just as story of a boy who feels awfully lonely. By setting the story in this time of brutal economic discontent, of rampant divorce among baby boomers, Reeves gives Let the Right One In great gravitas, conflating the political with human feeling so that Owen’s struggle becomes that of an entire nation of suffering, desperate, naïve people looking for a savior. Gonzalez

If a horror film can be reasonably likened to a bear trap, then the audience’s enjoyment, with exceptions, probably resides mostly in the first two acts as the filmmakers go about gradually winding and setting the spring. With Berberian Sound Studio, writer-director Peter Strickland has found an unusual solution for providing a catharsis that doesn’t compromise the dread he’s conjured: He doesn’t provide one at all, and that violation of narrative expectation is more disturbing than the emergence of a third-act ghoulie. In fact, one can reasonably assert that Berberian Sound Studio isn’t so much a horror film as an unusual workplace drama that follows a hero who’s having a very bad professional go of things. Chuck Bowen

Maniac (2012)

Made in collaboration with Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur, and with the sort of fearless artistic freedom often allowed by European financing, Franck Khalfoun’s Maniac begins with a psychopath’s synth-tastically scored stalking of a party girl back to her apartment, outside which he cuts her frightened scream short by driving a knife up into her head through her jaw. The film deceptively delights in capturing the mood of an exploitation cheapie before latching onto and running with the conceit only halfheartedly employed by William Lustig in the 1980 original, framing the titular maniac’s killing spree—this time set in Los Angeles—almost entirely from his point of view. A gimmick, yes, but more than just a means of superficially keying us into the psyche of the main character, Frank, an antique mannequin salesman played memorably by a minimally seen Elijah Wood. As in Rob Zombie’s Halloween II, this approach becomes a provocative means of sympathizing with the devil. Gonzalez

Marebito (2004)

One of the most Lovecraftian films not directly cribbed from the master’s pen, Takeshi Shimizu’s disquieting Marebito plumbs the phenomenology of fear. When amateur shutterbug Masuoka (Shinya Tsukamoto) witnesses a brutal act of self-destruction, he sets off on a quest the leads into bizarre subterranean regions from whence he rescues a naked girl he names F (Tomomi Miyashita), a mute, lethargic creature who subsists exclusively on blood and just might be his daughter. Shimizu floats several possible explanations for the inscrutable goings on (least interesting among them the idea that Masuoka has simply flipped his wig), but never settles definitively on any one of them. It’s precisely this disorienting sense of epistemological uncertainty that lends Marebito its power to disturb and fascinate in equal measure. Wilkins

Piranha 3D (2010)

Piranha 3D tips its cap to Jaws with an opening appearance by Richard Dreyfuss, yet the true ancestors of Alexandre Aja’s latest are less Steven Spielberg’s classic (and Joe Dante and Roger Corman’s more politically inclined 1978 original Piranha) than 1980s-era slasher films. Unapologetically giddy about its gratuitous crassness, Aja’s B movie operates by constantly winking at its audience, and while such self-consciousness diffuses any serious sense of terror, it also amplifies the rollicking comedy of its over-the-top insanity. Aja’s gimmicky use of 3D is self-aware, and the obscene gore of the proceedings is, like its softcore jokiness, so extreme and campy—epitomized by a hair-caught-in-propeller scalping—that the trashy, merciless Piranha 3D proves a worthy heir to its brazen exploitation-cinema forefathers. Schager

Sinister (2012)

Scott Derrickson’s Sinister isn’t a period piece, but by directing its attention backward it brackets its chosen tech-horror particulars as products of a bygone era—in this case considerably further back than the period of tube TVs and quarter-inch tapes to which this subgenre of horror so often belongs. Much like Ringu, Sinister concerns a cursed film whose audience dies after exposure to it, but here the curse is disseminated not by clunky videotape, but by a box of 8mm films. The projector, more than simply outmoded, is regarded here as practically archaic, and as with Berberian Sound Studio and its reel-to-reel fetishism, Sinister makes quite a show of the mechanics of the machine, soaking in the localized details and milking them for their weighty physicality. Even the format’s deficiencies, from the rickety hum of sprockets to the instability of the frame, are savored by what seems like a nostalgic impulse—a fondness for the old-fashioned that even transforms the rough, granular quality of the haunted films themselves into something like pointillist paintings of the macabre. Calum Marsh

28 Days Later (2002)

Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later is a post-apocalyptic zombie movie indebted to the traditions of John Wyndham and George A. Romero, opening with its young hero wandering abandoned streets calling out “Hello! Hello!” into the void. A marvel of economic storytelling, the film follows a handful of survivors that evaded a deadly “Rage” virus that tore across England, the riots and destruction that ensued, and the legion of infected victims who roam the streets at night for human meat. A bleak journey through an underground tunnel brings to mind one of the finest chapters in Stephen King’s The Stand; similar such references are far from being smug in-jokes, but rather uniquely appreciative of previous horror texts. The Rage virus itself feels particularly topical in our angry modern times. But maybe the more appropriate metaphor is that anyone who’s struggled through a grouchy, apocalyptic mood during 28 days of nicotine/drug/alcohol withdrawal will find their hostile sentiments reflected in this anger-fueled nightmare odyssey. Jeremiah Kipp

In making Amer as cold, calculating, and totally transfixing as they have, Belgian filmmakers Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani have manically constructed what may very well be a super giallo. Full of free-floating signifiers of victims watching killers, killers watching victims, and victims becoming killers, the film is essentially an academic’s tract on how the Italian giallo functions as a genre. And yet, it’s edited so masterfully and filmed with such a sadistically attentive eye for detail that it never feels intractably stiff. Every scene has a new color scheme, a new way to visually process sexual identification. Catte and Forzani prioritize their roles so that they impress us as visual artists that also happen to be capable theorists. The film’s narrative progression—the first act is Bava, the second is Fulci, and the third is Argento—is subsequently relentless while its dazzling kaleidoscopic aesthetic calls attention to its filmmakers’ brash know-how. It’s the ultimate cinematic fetish object—all close-ups, no mercy. Abrams

David Lynch’s meta noir Mulholland Drive literalizes the theory of surrealism as perpetual dream state. Told as it is using a highly symbolic, ravishingly engorged language of dreams, this bloody valentine to Los Angeles naturally leaves one feeling groggy, confused, looking forward and back, hankering to pass again through its serpentine, slithery hall of mirrors until all its secrets have been unpacked. Whether Mulholland Drive anticipated the YouTube Age we live in (and which Inland Empire‘s digital punk poetics perfectly embody) is up for debate, but there’s no doubt that this movie-movie will continue to haunt us long after Lynch has moved on to shooting pictures using the tools of whatever new film medium awaits us—tools that he will no doubt have helped to revolutionize. Gonzalez

JxSxPx's rating:

Navigating a tonal tightrope between tenderness and terror, Lucky McKee’s May ultimately resembles the patchwork creature that’s pieced together in its gruesome final act. This monstrous meditation on E.M. Forster’s motto “Only connect!” chronicles a pathetic, pent-up wallflower’s (Angela Bettis) attempts to establish “normal” relations with colleagues at a veterinary surgery and a potential love object or two. This proves a fool’s errand, since McKee surrounds her with a supporting cast of disobliging caricatures—predatory lesbian, self-absorbed artiste, daft L.A. punk. There’s a sly sense of humor at work here, never more apparent than during a risibly pretentious student film. McKee delivers several queasily disturbing set pieces along the way, especially one involving a roomful of blind children and lots of shattered glass. Wilkins

JxSxPx's rating:

The Invitation (2015)

The Invitation filters each sinister development through Will’s (Logan Marshall-Green) unreliable perspective, to the point that one friend’s failure to turn up at a lavish dinner, or another’s precipitous departure, appear as if submerged, changing with each shift in the emotional current. Returning to the rambling house where he and Eden once lived for the first time since the death of their son, Will finds himself inundated anew by his heartache, and the film, which otherwise hews to crisp, clean realism, is run through with these painful stabs of memory. Eden slashes her wrists in the kitchen sink, the sounds of children playing emanate from the empty yard, inane talk of the Internet’s funny cats and penguins becomes white noise against Will’s screaming: The question of whether or not to trust his sense of foreboding is perhaps not so open as director Karyn Kusama and company might wish, but against the terrors of continuing on after losing a child, the issue of narrative suspense is almost immaterial. Matt Brennan

Grim aesthetics and an even grimmer worldview define Black Death, in which ardent piousness and defiant paganism both prove paths toward violence, hypocrisy, and hell. Christopher Smith’s 14th-century period piece exudes an oppressive sense of physical, spiritual, and atmospheric weight, with grimy doom hanging in the air like the fog enshrouding its dense forests. His story concerns a gang of thugs, torturers, and killers led by Ulric (Sean Bean), a devout soldier commissioned by the church to visit the lone, remote town in the land not afflicted by a fatal pestilence, where it’s suspected a necromancer is raising the dead. Dario Poloni’s austere script charts the crew’s journey into a misty netherworld where the viciousness of man seems constantly matched by divine cruelty, even as the role of God’s hand—in the pestilence, and in the personal affairs of individuals—remains throughout tantalizingly oblique. Nick Schager

Don't Breathe (2016)

With Don’t Breathe, Fede Alvarez triumphantly suggests, through a seamless patchwork of near-escapes, an almost blackly comic spin on the classic Looney Tunes gag of characters running in and out of doors in a whirl of chaotic energy. In a more explicit riff of the Audrey Hepburn-starring Wait Until Dark, the story’s would-be thieves are pitted against a man who turns out to be blind, though far from the feeble victim they imagined, and so their only hope of escape becomes their impossible silence. The sounds of things and objects, from creaky floorboards to cellphones, are both tip-offs and methods of distraction. In one scene, Stephen Lang’s gun-toting veteran charges down the hall in a fury and directly past Dylan Minnette’s Alex, and as the young man presses his back against the wall, the expression on his face could be our own for how it recognizes the simultaneous horror and absurdity of his predicament. Ed Gonzalez

Them (2006)

Hoody-clad sadists attack a couple, alone in their country home. That’s all the setup that co-writers/directors David Moreau and Xavier Palud need to dredge up some uniquely discomfiting chills. You won’t be able to shake Them after seeing it because it’s scary without being grisly or full of cheap jump scares. Instead, it’s a marvel of precise timing and action choreography. The silence that deadens the air between each new assault becomes more and more disquieting as the film goes on. Likewise, the house where Them is primarily set in seems to grow bigger with each new hole the film’s villains tear out of. To get the maximum effect, be sure to watch this one at night; just don’t watch it alone. Simon Abrams

People who voted for this also voted for

Games of 2001 - ranked by preference

Games of 2007 - ranked by preference

Games of 2002 - ranked by preference

Strange and Beautiful

2017: Films I've Watched in August

Wild Wild West

Beautiful Models: Nicole Meyer

Christian Bale Films: Ranked

Tales of the Jazz Age

Best Batman Movies Countdown

Games I'm after

Movies watched in 2017

From Best To Worst: Varg Veum

Films I've Seen in 2017 (August)

Best movies 1990-1999

More lists from JxSxPx

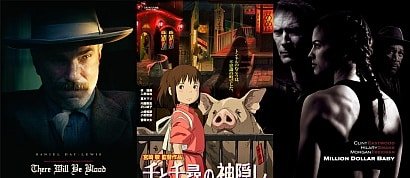

The Top 40 Sci-Fi Movies of the 21st Century

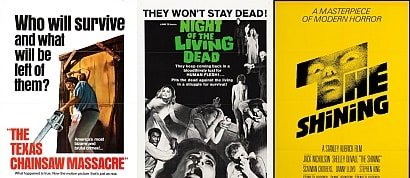

Slant’s 100 Greatest Horror Films – 2018 Edition

RS: 40 Greatest Punk Albums of All-Time

The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century So Far

100 Greatest American Albums of All Time

EW's The 25 Best Texas Movies

Slant’s 100 Greatest Horror Films – 2013 Edition

Login

Login

377

377

6.6

6.6

6.5

6.5