louse

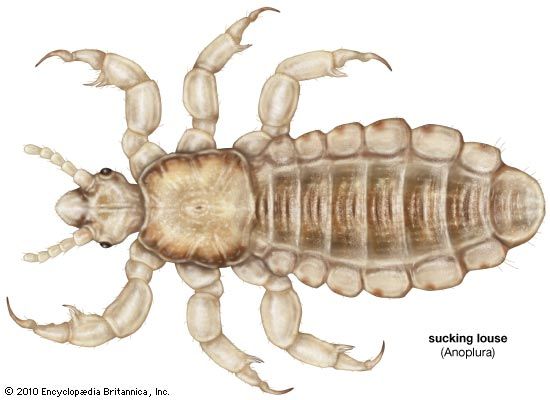

louse, (order Phthiraptera), any of a group of small wingless parasitic insects divisible into two main groups: the Amblycera and Ischnocera, or chewing or biting lice, which are parasites of birds and mammals, and the Anoplura, or sucking lice, parasites of mammals only. One of the sucking lice, the human louse, thrives in conditions of filth and overcrowding and is the carrier of typhus and louse-borne relapsing fever. Outbreaks of louse-borne diseases were frequent by-products of famine, war, and other disasters before the advent of insecticides (see infectious disease). Partly due to the widespread use of insecticidal shampoos for control, the head louse has developed resistance to many insecticides and is exhibiting a resurgence in many areas of the world. Heavy infestations of lice may cause intense skin irritation, and scratching for relief may lead to secondary infections. In domestic animals, rubbing and damage to hides and wool may also occur, and meat and egg production may be reduced. In badly infested birds, the feathers may be severely damaged. One of the dog lice is the intermediate host of the dog tapeworm, and a rat louse is a transmitter of murine typhus among rats.

General features

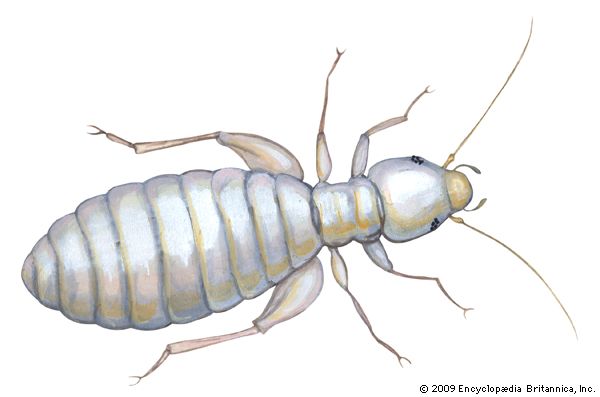

The flattened bodies of lice range from 0.33 mm to 11 mm (0.013 to 0.433 inch) in length and are whitish, yellow, brown, or black. Probably all species of birds have chewing lice, and most mammals have either chewing or sucking lice (Anoplura) or both. There are about 2,900 known species of Amblycera and Ischnocera, with many others still undescribed, and about 500 species of Anoplura. No lice have been taken from the platypus (duckbill) or from anteaters and armadillos, and none are known from bats or whales. The density of louse populations varies enormously on different individuals and also varies seasonally. Sick animals and birds with damaged bills, probably because of the absence of grooming and preening, may have abnormally large numbers: more than 14,000 have been reported on a sick fox and more than 7,000 on a cormorant with a damaged bill. The numbers found on healthy hosts are usually considerably smaller. Apart from grooming and preening by the host, lice and their eggs may be controlled by predatory mites, dust baths, intense sunlight, and continuous wetting.

Natural history

Life cycle

With the exception of the human body louse, lice spend their entire life cycle, from egg to adult, on the host. The females are usually larger than the males and often outnumber them on any one host. In some species males are rarely found, and reproduction is by unfertilized eggs (parthenogenetic). The eggs are laid singly or in clumps, usually cemented to a feather or hair. The human body louse lays its eggs on clothing next to the skin. The eggs may be simple ovoid structures glistening white among the feathers or hairs or may be heavily sculptured or ornamented with projections that assist in the attachment of the egg or serve in gas exchange. When the nymph within the egg is ready to hatch, it sucks in air through its mouth. The air passes through the alimentary canal and accumulates behind the nymph until sufficient pressure is built up to force off the egg cap (operculum). In many species the nymph also has a sharp platelike structure, the hatching organ, in the head region, which is also used to open the operculum. The emergent nymph is similar to the adult but is smaller and uncoloured, has fewer hairs, and differs in certain other morphological details.

Metamorphosis in the lice is simple, the nymphs molting three times, each of the three stages between molts (instars) becoming larger and more like the adult. The duration of the different stages of development varies from species to species and within each species according to temperature. In the human louse the egg stage may last from six to 14 days and the stages from hatching to adult, eight to 16 days. The life cycle may be closely correlated with the particular habits of the host; e.g., the louse of the elephant seal must complete its life cycle during the three to five weeks, twice a year, that the elephant seal spends onshore.

Ecology

Sucking lice feed exclusively on blood and have mouthparts well adapted for this purpose. The delicate stylets are used to pierce the skin, and a salivary secretion is injected to prevent coagulation while the blood is sucked into the mouth. The stylets are retracted into the head when the louse is not feeding. The chewing lice of birds feed on feathers, or on feathers, blood, and tissue fluids, or on fluids only. The fluids are obtained either by gnawing the skin or, as in the poultry body louse, from the central pulp of a developing feather. The feather-eating Mallophaga are able to digest the keratin of feathers. It is probable that the chewing lice of mammals do not feed on wool or hairs but on skin debris, secretions, and perhaps sometimes blood and tissue fluids.

Many birds and mammals are infested by more than one species of lice. Many species of birds have at least four or five louse species. Each species has specific adaptations that allows it to inhabit specific areas of the host’s body. Among the avian chewing lice, some species occupy different body regions for resting, feeding, and egg laying. A louse is unable to live for more than short periods of time away from its host, and adaptations serve to maintain its close contact. It is attracted by body heat and repelled by light, which causes the louse to stay within the warmth and darkness of the host’s plumage or pelage. It is also probably sensitive to the smell of its host and the peculiarities of feathers and hairs that help the louse orient itself. A louse may leave its host temporarily to pass to another host of the same species or to a host of another species, such as from prey to predator. Chewing lice have often been found attached to louse flies (Hippoboscidae), also parasitic on birds and mammals, and on other insects by which they may be transferred to a new host. However, they may not be able to establish themselves on the new host because of chemical or physical incompatibility with the host as food or habitat. Some mammalian lice, for example, can lay their eggs only on hairs of a suitable diameter.

The infrequency of transfer from one host species to another leads to host specificity, or host restriction, in which a species of louse is found only on one species of host or a group of closely related host species. It is probable that some host-specific species have developed through isolation because there is simply no opportunity for the transfer of lice. Domestic and zoo animals sometimes have established populations of lice from different hosts, and pheasants and partridges often have flourishing populations of chicken lice. Heterodoxus spiniger, which is parasitic on domestic dogs in tropical regions, was most likely acquired relatively recently from an Australian marsupial.

Form and function

The louse body is flattened dorsoventrally with the long axis of the head horizontal, enabling it to lie close along the feathers or hairs for attachment or feeding. The shape of the head and body varies considerably, especially in the avian chewing lice, in adaptation to the different ecological niches on the body of the host. Birds with white plumage, such as swans, have a white body louse, while the dark-plumaged coot has an almost black body louse. The antennae are short, three- to five-segmented, sometimes modified in the male as clasping organs to hold the female during copulation. The mouthparts are biting in the Mallophaga and strongly modified for sucking in the Anoplura. The Anoplura have three stylets enclosed in a sheath within the head, and a small proboscis armed with recurved toothlike processes, probably for holding the skin during feeding. The elephant louse has chewing mouthparts, with the modified mandibles borne on the end of a long proboscis. The thorax may have three visible segments, may have either the mesothorax and metathorax fused, or may have all three fused into a single segment as in the Anoplura. The legs are well developed with the tarsus being one- to two-segmented. There are two claws in the avian inhabiting Mallophaga and a single claw in some of the mammal-infesting families. The Anoplura have a single claw opposed to a tibial process forming a hair-clasping organ.

The abdomen has eight to 10 visible segments. There is one pair of thoracic breathing pores (spiracles) and a maximum of six abdominal pairs. The eversible male genitalia provide important characters for the classification of species. The female has no well-defined ovipositor, but various lobes present on the last two segments of some species may act as guides to the eggs during laying. The alimentary canal in the Mallophaga is composed of the esophagus, a well-developed crop and midgut, a smaller hindgut, four malpighian tubules, and a rectum with six papillae. The crop is either a simple swelling between esophagus and midgut or a diverticulum from the esophagus. In the Anoplura the esophagus passes straight into the large midgut with or without a swelling forming a crop. There is also a strong pump, associated with the esophagus, for sucking up the blood. Members of the superfamily Amblycera have well-developed, comblike structures at the base of the crop, which prevent undigested feather parts or other particles from passing into the midgut; in the family Philopteridae these combs are smaller and lie at the anterior part of the crop, whereas the Trichodectidae and Anoplura have no crop teeth. Apart from the eyes, which are sensitive to light, the other sensory structures are the tactile hairs and the sense organs in the mouth and on the antenna, some of which function as taste and smell organs.