Abstract

Cooperative hunting has been documented for several group-living carnivores and had been invoked as either the cause or the consequence of sociality. We report the first detailed observation of cooperative hunting for a solitary species, the Malagasy fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox). We observed a 45 min hunt of a 3 kg arboreal primate by three male fossas. The hunters changed roles during the hunt and subsequently shared the prey. We hypothesize that social hunting in fossas could have either evolved to take down recently extinct larger lemur prey, or that it could be a by-product of male sociality that is beneficial for other reasons.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The vast majority of carnivores are solitary (80–95%: Bekoff et al. 1984) and are therefore found to hunt alone. The combined action of several individuals to take down and share prey has been described for several group-living carnivores, such as lions (Schaller 1972; Packer et al. 1990), wild dogs (Estes and Goddard 1967; Creel and Creel 1995), wolves (Mech 1970), and hyenas (Kruuk 1972, 1975; Mills 1990). Indeed, it has been suggested that cooperative hunting is closely linked to the social organization of a species, either being the cause of sociality (Creel and Creel 1995) or its consequence (Packer and Ruttan 1988). It has been suggested that cooperative hunting may favor sociality when the prey is too large or too difficult to be taken down by a single individual (Schaller 1972; Kruuk 1975; Creel and Creel 1995). Similarly, sociality may offer the possibility of hunting socially, thereby extending the range of prey species secondarily (Schaller 1972). So far, cooperative hunting of nongregarious carnivores has been described only once anecdotally for the solitary Canadian lynx (Lynx canadensis; Barash 1971). Therefore, whether and why solitarily ranging and foraging individuals associate to hunt together remains unclear. Here, we report the first detailed observation of an unusual case of cooperative hunting in an otherwise solitary carnivore, the fossa.

The fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) is the largest extant member of the Madagascar mongooses (Eupleridae). It is restricted to Madagascar and potentially widespread on the island but threatened by habitat loss. Males (≤12 kg) are heavier than females (<9 kg). Fossas are adapted to arboreal locomotion through their short muscular limbs and a long tail. Nevertheless, in the dry deciduous forests of western Madagascar, they are frequently found on the ground and climb up trees only for hunting or mating. Fossas are exclusively carnivorous, feeding on a variety of vertebrates, but mostly lemurs and tenrecs (Hawkins and Racey 2008). Their social organization has been classified as solitary because individuals are usually encountered alone (Hawkins and Racey 2005). However, a number of anecdotal reports of social hunting have accumulated over the past 16 years from Kirindy Forest/CFPF and Andasibe-Mantadia National Park (Table 1). These hunting events typically included two individuals and were directed towards the highly agile sifakas (genus Propithecus, Primates).

Materials and methods

This observation was made coincidentally on 29 September 2007 during the course of a study on fossa behavioral ecology in Kirindy Forest/CFPF, a dry deciduous forest in central western Madagascar. This forest is characterized by pronounced seasonality. During a long dry season (May–October), little or no rain falls and fossas suffer from water scarcity, low food availability and lack of cover. In the dry season, fossas exert considerable predation pressure on lemurs (>50% of their diet), with a clear preference for larger species (Rasoloarison et al. 1995; Hawkins and Racey 2008). The largest extant lemur in Kirindy Forest/CFPF is Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi). Sifakas are arboreal vertical clingers and leapers, weigh up to 3.5 kg, and live in mixed-sex groups of four adult individuals on average (Kappeler and Schäffler 2008). The following observation was made from wooden shelters usually used as housing for researchers at the field station of the German Primate Center, which is located in Kirindy Forest/CFPF. The shelters are distributed in the forest around the central camp site and will be denoted by letters according to their order of occurrence during the course of the hunt.

Results

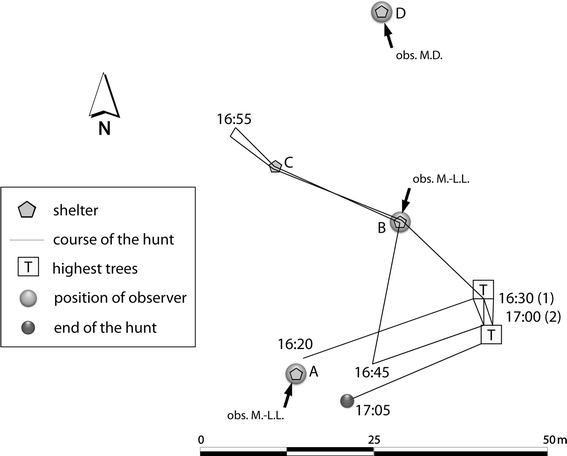

We were attracted to the situation by three male fossas passing by the camp site in single file and subsequent terrestrial predator alarm calls uttered by a group of sifakas (Fichtel and Kappeler 2002). One observer (M.-L. L.) followed the fossas and could observe the complete course of the hunt from a distance of about 5–30 m. When the observer arrived at shelter A (Fig. 1; 16:20), one sifaka had been isolated from its group.

Two fossas climbed up two different trees and chased the sifaka in an easterly direction. The third fossa followed the sifaka on the ground. The latter fled up the highest tree in the area, where it was forced to jump to the neighboring second-highest tree by a climbing fossa. A sequence of five changes between the two trees (ca. 15 m in height) then occurred, where one fossa consistently followed the sifaka. On each occasion the sifaka climbed up to the highest point of the tree, the fossa came as close as 5 m to it, and then the sifaka jumped to the neighboring tree. A second fossa climbed up smaller trees surrounding the scene but could not find access to the sifaka. The third fossa moved rapidly on the ground. During the chase, a breaking branch caused one fossa to fall to the ground. Thereafter, the hunt paused for 12 min. The sifaka stayed at the top of the highest tree and lowered the volume and frequency of its alarm calls.

When the hunt resumed, the fossas changed their hunting behavior. Instead of one fossa following the sifaka, two individuals alternated in climbing up the two highest trees until the lemur jumped again to the other one. This again led to a sequence of changes between the two trees until two fossas appeared simultaneously in both trees and forced the sifaka to jump into the lower canopy. One fossa followed up in the tree, another on the ground. The third lay down on a branch for a moment and did not follow until the hunt went on in a westerly direction. Then the two fossas up in the trees chased the sifaka back in a northerly direction, with the third following the sifaka on the ground. At shelter B, one observer (M.-L. L.) was surrounded by the animals and observed that the three fossas alternated in their roles of chasing through trees and following along the ground, and that they vocalized with each other via guttural sounds, which are well known to be uttered in aggressive interactions (Albignac 1973). The chase proceeded in the direction of shelter C, close to shelter D, where the second observer was located (M. D.). M. D. reported that the guttural vocalization always preceded a change in the hunting roles among the fossas, but none of the observers could determine which of the fossas emitted the vocalization and which of them was the intended receiver for it. At this stage, the chase speeded up and the fossas never jumped more than twice behind the sifaka before they alternated with another individual. The sifaka fled back to the highest trees and was chased afterwards in a southern direction to shelter A. By now, all three fossas were hunting up in the trees and jumped as quickly and as far as the lemur. After another fall by one of the fossas and the subsequent reformation of the hunters, they finally succeeded in driving the lemur towards the ground, where they rapidly took it down (17:05). A choking scream emitted by the sifaka indicated that it was killed by a throat bite, but the actual killing occurred out of view. One observer (M.-L. L.) hid in shelter C in order to observe the fossas feeding on their prey; the carcass itself was out of view, but sounds clearly indicated feeding activity.

During the following feeding bout, the males shared the prey without apparent aggression. While one male was waiting at shelter C, the other two fed together on the carcass. Fifteen minutes later, one male left the remains and retired under shelter C. Only then did the third male approach the carcass and started feeding. The two males fed together for 13 min and then the second male returned to the shelter to rest. The third male joined the other two another 5 min later and all fossas rested together. At 17:50, all three males set off together in the direction of the remains and finally left the area at 18:00.

Discussion

Cooperative hunting has only been described for gregarious carnivores, and has been explained for group-living species by a number of factors relating to prey or predator. Prey that is difficult to hunt might necessitate the cooperative action of several individuals to hunt successfully (Kruuk 1972, 1975; Schaller 1972). For example, the chances of taking down highly resistant or agile prey may be unlikely when hunting alone. One main prey type for fossas are sifakas (Hawkins and Racey 2008; Wright et al. 1997), which are highly agile arboreal leapers and thus difficult to hunt in three-dimensional space. It has been argued that a similar challenge has led to complex cooperative hunting behavior in chimpanzees, which even includes the individuals involved adopting different hunting roles (Boesch 2002). Given the agility of their prey, single fossas may find it difficult to catch sifakas other than by ambush at night.

Cooperative hunting can also be advantageous when the prey is too large to be taken down by a single individual. With a body mass of 3 kg, sifakas are much smaller than fossas. Furthermore, the per capita energy intake from a sifaka prey may not be sufficient to fuel a 35-min intensive chase of several hunting individuals, as we reported here. However, prey size may have played a role in the evolution of cooperative hunting in fossas because the fauna of Madagascar has changed dramatically in the recent past. Only 500–1,500 years ago, larger lemurs such as the giant sloth lemurs that became extinct most recently, and weighed 9–55 kg, were widely distributed across the island (Godfrey and Jungers 2003). Even though these lemurs may have been mainly preyed upon by the extinct giant fossa (Cryptoprocta spelea; Goodman et al. 2004), its smaller congener may have hunted sloth lemurs through joint action. Hence, fossas could have evolved cooperative hunting to take down larger lemur prey. Because this type of prey went extinct quite recently, this behavior may still exist, although it is of little benefit now.

Alternatively, hunting associations may be a by-product of sociality when associating is beneficial for other reasons, such as the communal protection of the young, and territory defence (e.g., lions; Packer et al. 1990; Fryxell et al. 2007; Mosser and Packer 2009). Fossas are most often encountered on their own and they inhabit wide ranges that seem to be exclusive, at least for females (Hawkins and Racey 2005). However, in Kirindy, mainly during the end of the dry season (coinciding with the annual mating season), males are frequently observed in close and stable associations (M.-L. Lührs, personal observation), indicating a possible function in reproductive context. The social organization of fossas may resemble that of cheetahs, where male coalitions consist of two to three individuals, most often brothers, that associate in order to jointly defend a territory and frequently hunt together (Caro and Collins 1987; Caro et al. 1989; Caro 1994). In the case of the fossa, males may primarily associate to jointly defend access to females in a highly competitive polyandrous mating system (Hawkins and Racey 2009). The existence of such male coalitions has also been reported for more closely related solitary mongooses (e.g., Waser et al. 1994), and may be a prerequisite for male sociality and social hunting.

In contrast, male–female associations in fossas have never been observed outside the mating season, except for mother–offspring dyads. It appears likely therefore that observations of males and females hunting socially include mothers and their male offspring.

Overall, cooperatively hunting carnivores show high plasticity in their social organization, ranging from otherwise unsynchronized individuals to highly cohesive groups (e.g., lions; Schaller 1972). Hence, fossas may represent the least gregarious species within a continuum of gregariousness among cooperatively hunting carnivores. A better understanding of the primary causes of sociality in fossas may therefore illuminate the relationship between gregariousness and food acquisition in carnivores in general.

References

Albignac R (1973) Mammifères carnivores. Faune de Madagascar. ORSTOM, Paris

Barash DP (1971) Cooperative hunting in the lynx. J Mammal 52:480

Bekoff M, Daniels TJ, Gittleman JL (1984) Life history patterns and the comparative social ecology of carnivores. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 15:191–232

Boesch C (2002) Cooperative hunting roles among Tai chimpanzees. Hum Nat 13:27–46

Caro TM (1994) Cheetahs of the Serengeti plains: group living in an asocial species. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Caro TM, Collins DA (1987) Ecological characteristics of territories of male cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). J Zool Lond 211:89–105

Caro TM, Fitzgibbon CD, Holt ME (1989) Physiological costs of behavioural strategies for male cheetahs. Anim Behav 38:309–317

Creel S, Creel NM (1995) Communal hunting and pack size in African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus. Anim Behav 50:1325–1339

Estes RD, Goddard J (1967) Prey selection and hunting behavior of the African wild dog. J Wildl Manage 31:52–70

Fichtel C, Kappeler PM (2002) Anti-predator behavior of group-living Malagasy primates: mixed evidence for a referential alarm call system. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 51:262–275

Fryxell JM, Mosser A, Sinclair ARE, Packer C (2007) Group formation stabilizes predator–prey dynamics. Nature 449:1041–1043

Godfrey LR, Jungers WL (2003) The extinct sloth lemurs of Madagascar. Evol Anthropol 12:252–263

Goodman SM, Rasoloarison RM, Ganzhorn JU (2004) On the specific identification of subfossil Cryptoprocta (Mammalia, Carnivora) from Madagascar. Zoosystema 26:129–143

Hawkins CE, Racey PA (2005) Low population density of a tropical forest carnivore, Cryptoprocta ferox: implications for protected area management. Oryx 39:35–43

Hawkins CE, Racey PA (2008) Food habits of an endangered carnivore, Cryptoprocta ferox, in the dry deciduous forests of western Madagascar. J Mammal 89:64–74

Kappeler PM, Schäffler L (2008) The lemur syndrome unresolved: extreme male reproductive skew in sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi), a sexually monomorphic primate with female dominance. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:1007–1015

Kruuk H (1972) The spotted hyena: a study of predation and social behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kruuk H (1975) Functional aspects of social hunting in carnivores. In: Baerends G, Beer C, Manning A (eds) Function and evolution in behaviour. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 119–141

Mech LD (1970) The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Natural History Press, Garden City

Mills MGL (1990) Kalahari hyaenas: comparative behavioural ecology of two species. Unwin Hyman, London

Mosser A, Packer C (2009) Group territoriality and the benefits of sociality in the African lion, Panthera leo. Anim Behav 78:359–370

Packer C, Ruttan L (1988) The evolution of cooperative hunting. Am Nat 132:159–198

Packer C, Scheel D, Pusey AE (1990) Why lions form groups: food is not enough. Am Nat 136:1–19

Rasoloarison RM, Rasolonandrasana BPN, Ganzhorn JU, Goodman SM (1995) Predation on vertebrates in the Kirindy Forest, western Madagascar. Ecotropica 1:59–65

Schaller GB (1972) The Serengeti lion: a study of predator–prey relations. Wildlife behavior and ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Waser PM, Keane B, Creel SR, Elliott LF, Minchella DJ (1994) Possible male coalitions in a solitary mongoose. Anim Behav 47:289–294

Wright PC, Heckscher SK, Dunham AE (1997) Predation on Milne–Edward’s sifaka (Propithecus diadema edwardsi) by the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) in the rain forest of southeastern Madagascar. Folia Primatol 68:34–43

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. D. Rakotondravony and Prof. O. Ramilijaona (University of Antananarivo), the Comission Tripartite de Direction des Eaux et Forêts, and the C.F.P.F. Morondava for their authorization. We also thank Nick Garbutt and our field assistants mentioned in the manuscript for their personal reports and Dr. Clare E. Hawkins and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on the manuscript. The fossa project was partly financed by Duisburg Zoo (Germany), the German Primate Center (DPZ), and the University of Göttingen. We thank Prof. Peter Kappeler for comments and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lührs, ML., Dammhahn, M. An unusual case of cooperative hunting in a solitary carnivore. J Ethol 28, 379–383 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-009-0190-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-009-0190-8