Biology:Megapiranha

| Megapiranha | |

|---|---|

| |

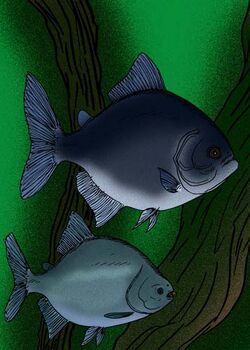

| Comparison of M. paranensis and the tambaqui | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Characiformes |

| Family: | Serrasalmidae |

| Genus: | †Megapiranha Cione et al. 2009 |

| Species: | †M. paranensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Megapiranha paranensis Cione et al. 2009

| |

Megapiranha is an extinct serrasalmid characin fish from the Late Miocene (8–10 million years ago) Ituzaingó Formation of Argentina , described in 2009.[1] The type species is M. paranensis.[2] It is thought to have been about 71 centimetres (28 in) in length and 10 kilograms (22 lb) in weight.[3] The holotype consists only of premaxillae and a zigzag tooth row; the rest of its body is unknown.[4] This dentition is reminiscent of both the double-row seen in pacus, and the single row seen in the teeth of modern piranhas, suggesting that M. paranensis is a transitional form. Its bite force is estimated between 1,240–4,749 N (279–1,068 lbf).[3]

History and naming

The holotype of Megapiranha was discovered in an unknown locality of the Ituzaingó Formation, Argentina , in the early 20th century near the towns of Paraná and Villa Urquiza. The specimen, a fragment of the animal's premaxilla containing several teeth, was later rediscovered by Alberto Luis Cione in the collection of the Museo de La Plata. An isolated tooth discovered in 1999 has also been referred to this genus.[4]

The name Megapiranha is a combination of the word "mega" in reference to the animal's large size and piranha, a common name for typically carnivorous members of Serrasalmidae. The word piranha itself is a Portuguese merging of words originating in the Tupi language and may have several meanings including "tooth fish",[5] "cutting fish", "devil fish"[6] or "biting fish".[7] The species name was chosen to reflect Megapiranhas place of origin near the city of Paraná.[4]

Description

Although only three teeth are fully preserved, the holotype specimen shows the presence of seven premaxillary teeth which are arranged in a zig-zag pattern with some overlap. The third, fourth and fifth tooth are preserved and all share very similar morphology with one another. Of these teeth the first and third formed the inner row, while the rest formed the outer row. In other serrasalmids the teeth are arranged either two rows of seven teeth with a morphologically distinct second tooth of the inner row (third tooth), such an arrangement is seen in the Tambaqui for instance, a zig-zag pattern of five teeth (like in Catoprion) or a single row of six teeth, which is typical for the carnivorous species.[4]

Each teeth only shows a single tooth crown the shape of an almost equilateral triangle, which sits atop a constriction of the tooth. Towards the apex of the crown the teeth take on a more sloping edge which is finely serrated in addition to slight labio-lingual compression. Much like in the arrangement of the teeth, Megapiranha differs significantly from its modern relatives. Pacus generally have more complex and broad teeth while true piranhas have teeth with multiple cusps, well developed serration and strong compression, making them thin and well suited for cutting. Between the three preserved teeth the size varies greatly, with the third being the largest and the fourth the smallest. The attachment scars likewise differ in size, showing a similar size distribution.[4]

The preserved premaxilla is almost straight and the teeth are all positioned on the same horizontal plane. The dorsal surface of the bone is slightly concave and slopes upwards towards the front as it transitions to the ascending process, which is barely tapering. Here too Megapiranha provides a unique combination of features amongst its family, with serrasalmids that share the straight axis of the premaxilla typically having a straight dorsal margin and two different planes on which the teeth are placed, while those with a single horizontal plane and concave dorsal surface lack a straight axis. The entire premaxilla is 6.9 cm (2.7 in) long with a rugose outer surface that most likely housed nerves and blood vessels. The symphyseal joint is interlocking.[4]

Based on the size of the holotype, Megapiranha has originally been estimated to have reached a length of 95–128 cm (37–50 in) and a weight of 73 kg (161 lb), larger than any other member of the family, living or extinct.[4] Later research using Serrasalmus rhombeus as a basis arrived at a more conservative size estimate of 71 cm (28 in) long and 10 kg (22 lb) heavy.[3]

Phylogeny

Megapiranha combines several traits known from more basal serrasalmids with those of derived members. Both the subcircular tooth attachment scars as well as the presence of seven, not six, teeth are in line with what is known from most members of the group, while the triangular shape of the crown, fine serration and slight labiolingual compression are more in line with the morphology seen in the teeth of true piranhas. The interdigitating symphyseal joint meanwhile draws parallels to basal pacus like Colossoma and Mylossoma, however differences in the structure of the joint between Megapiranha and extant forms suggests that this trait developed independently from one another.[4]

This unique combination of characters supports the idea that within serrasalmids an evolutionary trend led to the shift from double-rowed dentition with broad teeth to the single row of flattened teeth observed in piranhas. Megapiranha represents an intermediate form between the two, with triangular, slightly compressed teeth but maintaining two rows of teeth that are still relatively broad.[4]

| Serrasalmidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

In the 2009 description of the genus, Cione and colleagues suggest that the dentition of Megapiranha may not have been a direct adaptation towards carnivory and likely helped the animal with a wide range of food sources. Part of their reasoning for this is the broad range of diets found within serrasalmids, including many herbivorous and omnivorous forms in addition to carnivores, as well as the highly specialised wimple piranha which feeds primarily on the scales of other fish.[4]

In 2012 Justin R. Grubich and colleagues suggest that the dentition of Megapiranha may have been a transitional form between feeding on hard prey and specialising in slicing flesh. To arrive at this conclusion, they conducted extensive measurements of the bite force of the extant Serrasalmus rhombeus as a standin for its Miocene relative. With this method they calculated a bite force of 1240 Newton for the smaller estimates and 4749 Newton for the older, larger size estimates. Even the more conservative estimates would put the biteforce of Megapiranha four times higher than that of the largest extant piranha species. The authors additionally note that the fact that the measurements were taken on live animals may lead to underestimates caused by fatigue and stress. Furthermore, the measurements were restricted to the anterior biteforce, not including the potential of doubled biteforce along the lower jaw. This may result in forces between 2480 and 9498 Newton.[3]

Tests using a bronze-alloy replica of Megapiranhas dentition showed that it would be able to penetrate the thick outer layer of a bovine femur, the shell of a turtle and the armor of certain catfish species. They conclude by suggesting that Megapiranha could have hypothetically fed on hard-shelled animals such as turtles, armored catfish and even attacked larger mammals. The shape of Megapiranhas teeth is infered to effectively focus stress at the tip of the teeth while piercing flesh before distributing its impact stresses throughout the base of the tooth while crushing hard material such as bones in a similar fashion to how Pacus crack hard-shelled fruits and nuts. However, this ecology is only hypothetical in the absence of any fossil material bearing the bite marks of Megapiranha.[3]

References

- ↑ Live Science: Toothy 3-foot Piranha Fossil Found

- ↑ Megapiranha at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Grubich, J.R.; Huskey, S.; Crofts, S.; Orti, G.; Porto, J. (2012). "Mega-Bites: Extreme jaw forces of living and extinct piranhas (Serrasalmidae)". Scientific Reports 2: 1009. doi:10.1038/srep01009. PMID 23259047. Bibcode: 2012NatSR...2E1009G.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Cione, Alberto Luis; Dahdul, Wasila M.; Lundberg, John G.; Machado-Allison, Antonio (2009). "Megapiranha paranensis, a new genus and species of Serrasalmidae (Characiformes, Teleostei) from the Upper Miocene of Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (2): 350. doi:10.1671/039.029.0221. (Summary of the paper).

- ↑ (in en) Scientific American, "Fishing on the Amazon". Munn & Company. 1880-11-06. pp. 293. https://books.google.com/books?id=6ok9AQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Britton, A. Scott. Guaraní: Guaraní-English, English-Guaraní ; concise dictionary. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2005. Print.

- ↑ "Piranha | Origin and meaning of piranha by Online Etymology Dictionary". https://www.etymonline.com/word/piranha.

External links

- "New fossil tells how piranhas got their teeth". eurekalert.org. 2009.

Wikidata ☰ Q21447457 entry

|