Biology:BRCA1

Generic protein structure example |

Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein is a protein that in humans is encoded by the BRCA1 (/ˌbrækəˈwʌn/) gene.[1] Orthologs are common in other vertebrate species, whereas invertebrate genomes may encode a more distantly related gene.[2] BRCA1 is a human tumor suppressor gene[3][4] (also known as a caretaker gene) and is responsible for repairing DNA.[5]

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are unrelated proteins,[6] but both are normally expressed in the cells of breast and other tissue, where they help repair damaged DNA, or destroy cells if DNA cannot be repaired. They are involved in the repair of chromosomal damage with an important role in the error-free repair of DNA double-strand breaks.[7][8] If BRCA1 or BRCA2 itself is damaged by a BRCA mutation, damaged DNA is not repaired properly, and this increases the risk for breast cancer.[9][10] BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been described as "breast cancer susceptibility genes" and "breast cancer susceptibility proteins". The predominant allele has a normal, tumor suppressive function whereas high penetrance mutations in these genes cause a loss of tumor suppressive function which correlates with an increased risk of breast cancer.[11]

BRCA1 combines with other tumor suppressors, DNA damage sensors and signal transducers to form a large multi-subunit protein complex known as the BRCA1-associated genome surveillance complex (BASC).[12] The BRCA1 protein associates with RNA polymerase II, and through the C-terminal domain, also interacts with histone deacetylase complexes. Thus, this protein plays a role in transcription, and DNA repair of double-strand DNA breaks[10] ubiquitination, transcriptional regulation as well as other functions.[13]

Methods to test for the likelihood of a patient with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 developing cancer were covered by patents owned or controlled by Myriad Genetics.[14][15] Myriad's business model of offering the diagnostic test exclusively led from Myriad being a startup in 1994 to being a publicly traded company with 1200 employees and about $500M in annual revenue in 2012;[16] it also led to controversy over high prices and the inability to obtain second opinions from other diagnostic labs, which in turn led to the landmark Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics lawsuit.[17]

Discovery

The first evidence for the existence of a gene encoding a DNA repair enzyme involved in breast cancer susceptibility was provided by Mary-Claire King's laboratory at UC Berkeley in 1990.[18] Four years later, after an international race to find it,[19] the gene was cloned in 1994 by scientists at University of Utah, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and Myriad Genetics.[14][20]

Gene location

The human BRCA1 gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17 at region 2 band 1, from base pair 41,196,312 to base pair 41,277,500 (Build GRCh37/hg19) (map).[21] BRCA1 orthologs have been identified in most vertebrates for which complete genome data are available.[2]

Protein structure

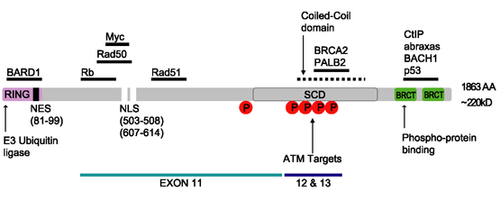

The BRCA1 protein contains the following domains:[22]

- Zinc finger, C3HC4 type (RING finger)

- BRCA1 C Terminus (BRCT) domain

This protein also contains nuclear localization signals and nuclear export signal motifs.[23]

The human BRCA1 protein consists of four major protein domains; the Znf C3HC4- RING domain, the BRCA1 serine domain and two BRCT domains. These domains encode approximately 27% of BRCA1 protein. There are six known isoforms of BRCA1,[24] with isoforms 1 and 2 comprising 1863 amino acids each.[citation needed]

BRCA1 is unrelated to BRCA2, i.e. they are not homologs or paralogs.[6]

Zinc ring finger domain

The RING motif, a Zn finger found in eukaryotic peptides, is 40–60 amino acids long and consists of eight conserved metal-binding residues, two quartets of cysteine or histidine residues that coordinate two zinc atoms.[26] This motif contains a short anti-parallel beta-sheet, two zinc-binding loops and a central alpha helix in a small domain. This RING domain interacts with associated proteins, including BARD1, which also contains a RING motif, to form a heterodimer. The BRCA1 RING motif is flanked by alpha helices formed by residues 8–22 and 81–96 of the BRCA1 protein. It interacts with a homologous region in BARD1 also consisting of a RING finger flanked by two alpha-helices formed from residues 36–48 and 101–116. These four helices combine to form a heterodimerization interface and stabilize the BRCA1-BARD1 heterodimer complex. Additional stabilization is achieved by interactions between adjacent residues in the flanking region and hydrophobic interactions. The BARD1/BRCA1 interaction is disrupted by tumorigenic amino acid substitutions in BRCA1, implying that the formation of a stable complex between these proteins may be an essential aspect of BRCA1 tumor suppression.[26]

The ring domain is an important element of ubiquitin E3 ligases, which catalyze protein ubiquitination. Ubiquitin is a small regulatory protein found in all tissues that direct proteins to compartments within the cell. BRCA1 polypeptides, in particular, Lys-48-linked polyubiquitin chains are dispersed throughout the resting cell nucleus, but at the start of DNA replication, they gather in restrained groups that also contain BRCA2 and BARD1. BARD1 is thought to be involved in the recognition and binding of protein targets for ubiquitination.[27] It attaches to proteins and labels them for destruction. Ubiquitination occurs via the BRCA1 fusion protein and is abolished by zinc chelation.[26] The enzyme activity of the fusion protein is dependent on the proper folding of the ring domain.[citation needed]

Serine cluster domain

BRCA1 serine cluster domain (SCD) spans amino acids 1280–1524. A portion of the domain is located in exons 11–13. High rates of mutation occur in exons 11–13. Reported phosphorylation sites of BRCA1 are concentrated in the SCD, where they are phosphorylated by ATM/ATR kinases both in vitro and in vivo. ATM/ATR are kinases activated by DNA damage. Mutation of serine residues may affect localization of BRCA1 to sites of DNA damage and DNA damage response function.[25]

BRCT domains

The dual repeat BRCT domain of the BRCA1 protein is an elongated structure approximately 70 Å long and 30–35 Å wide.[28] The 85–95 amino acid domains in BRCT can be found as single modules or as multiple tandem repeats containing two domains.[29] Both of these possibilities can occur in a single protein in a variety of different conformations.[28] The C-terminal BRCT region of the BRCA1 protein is essential for repair of DNA, transcription regulation and tumor suppressor function.[30] In BRCA1 the dual tandem repeat BRCT domains are arranged in a head-to-tail-fashion in the three-dimensional structure, burying 1600 Å of hydrophobic, solvent-accessible surface area in the interface. These all contribute to the tightly packed knob-in-hole structure that comprises the interface. These homologous domains interact to control cellular responses to DNA damage. A missense mutation at the interface of these two proteins can perturb the cell cycle, resulting a greater risk of developing cancer.[citation needed]

Function and mechanism

BRCA1 is part of a complex that repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. The strands of the DNA double helix are continuously breaking as they become damaged. Sometimes only one strand is broken, sometimes both strands are broken simultaneously. DNA cross-linking agents are an important source of chromosome/DNA damage. Double-strand breaks occur as intermediates after the crosslinks are removed, and indeed, biallelic mutations in BRCA1 have been identified to be responsible for Fanconi Anemia, Complementation Group S (FA-S),[31] a genetic disease associated with hypersensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents. BRCA1 is part of a protein complex that repairs DNA when both strands are broken. When this happens, it is difficult for the repair mechanism to "know" how to replace the correct DNA sequence, and there are multiple ways to attempt the repair. The double-strand repair mechanism in which BRCA1 participates is homology-directed repair, where the repair proteins copy the identical sequence from the intact sister chromatid.[32] FA-S is almost always a lethal condition in utero; only a handful cases of biallelic BRCA1 mutations have been reported in literature despite the high carrier frequencies in the Ashkenazim, and none since 2013.[33]

In the nucleus of many types of normal cells, the BRCA1 protein interacts with RAD51 during repair of DNA double-strand breaks.[34] These breaks can be caused by natural radiation or other exposures, but also occur when chromosomes exchange genetic material (homologous recombination, e.g., "crossing over" during meiosis). The BRCA2 protein, which has a function similar to that of BRCA1, also interacts with the RAD51 protein. By influencing DNA damage repair, these three proteins play a role in maintaining the stability of the human genome.[35]

BRCA1 is also involved in another type of DNA repair, termed mismatch repair. BRCA1 interacts with the DNA mismatch repair protein MSH2.[36] MSH2, MSH6, PARP and some other proteins involved in single-strand repair are reported to be elevated in BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors.[37]

A protein called valosin-containing protein (VCP, also known as p97) plays a role to recruit BRCA1 to the damaged DNA sites. After ionizing radiation, VCP is recruited to DNA lesions and cooperates with the ubiquitin ligase RNF8 to orchestrate assembly of signaling complexes for efficient DSB repair.[38] BRCA1 interacts with VCP.[39] BRCA1 also interacts with c-Myc, and other proteins that are critical to maintain genome stability.[40]

BRCA1 directly binds to DNA, with higher affinity for branched DNA structures. This ability to bind to DNA contributes to its ability to inhibit the nuclease activity of the MRN complex as well as the nuclease activity of Mre11 alone.[41] This may explain a role for BRCA1 to promote lower fidelity DNA repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).[42] BRCA1 also colocalizes with γ-H2AX (histone H2AX phosphorylated on serine-139) in DNA double-strand break repair foci, indicating it may play a role in recruiting repair factors.[13][43]

Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde are common environmental sources of DNA cross links that often require repairs mediated by BRCA1 containing pathways.[44]

This DNA repair function is essential; mice with loss-of-function mutations in both BRCA1 alleles are not viable, and as of 2015 only two adults were known to have loss-of-function mutations in both alleles (leading to FA-S); both had congenital or developmental issues, and both had cancer. One was presumed to have survived to adulthood because one of the BRCA1 mutations was hypomorphic.[45]

Transcription

BRCA1 was shown to co-purify with the human RNA Polymerase II holoenzyme in HeLa extracts, implying it is a component of the holoenzyme.[46] Later research, however, contradicted this assumption, instead showing that the predominant complex including BRCA1 in HeLa cells is a 2 megadalton complex containing SWI/SNF.[47] SWI/SNF is a chromatin remodeling complex. Artificial tethering of BRCA1 to chromatin was shown to decondense heterochromatin, though the SWI/SNF interacting domain was not necessary for this role.[43] BRCA1 interacts with the NELF-B (COBRA1) subunit of the NELF complex.[43]

Mutations and cancer risk

Certain variations of the BRCA1 gene lead to an increased risk for breast cancer as part of a hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome. Researchers have identified hundreds of mutations in the BRCA1 gene, many of which are associated with an increased risk of cancer. Females with an abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have up to an 80% risk of developing breast cancer by age 90; increased risk of developing ovarian cancer is about 55% for females with BRCA1 mutations and about 25% for females with BRCA2 mutations.[49]

These mutations can be changes in one or a small number of DNA base pairs (the building-blocks of DNA), and can be identified with PCR and DNA sequencing.[50]

In some cases, large segments of DNA are rearranged. Those large segments, also called large rearrangements, can be a deletion or a duplication of one or several exons in the gene. Classical methods for mutation detection (sequencing) are unable to reveal these types of mutation.[51] Other methods have been proposed: traditional quantitative PCR,[52] multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA),[53] and Quantitative Multiplex PCR of Short Fluorescent Fragments (QMPSF).[54] Newer methods have also been recently proposed: heteroduplex analysis (HDA) by multi-capillary electrophoresis or also dedicated oligonucleotides array based on comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH).[55]

Some results suggest that hypermethylation of the BRCA1 promoter, which has been reported in some cancers, could be considered as an inactivating mechanism for BRCA1 expression.[56]

A mutated BRCA1 gene usually makes a protein that does not function properly. Researchers believe that the defective BRCA1 protein is unable to help fix DNA damage leading to mutations in other genes. These mutations can accumulate and may allow cells to grow and divide uncontrollably to form a tumor. Thus, BRCA1 inactivating mutations lead to a predisposition for cancer.[citation needed]

BRCA1 mRNA 3' UTR can be bound by an miRNA, Mir-17 microRNA. It has been suggested that variations in this miRNA along with Mir-30 microRNA could confer susceptibility to breast cancer.[57]

In addition to breast cancer, mutations in the BRCA1 gene also increase the risk of ovarian and prostate cancers. Moreover, precancerous lesions (dysplasia) within the fallopian tube have been linked to BRCA1 gene mutations. Pathogenic mutations anywhere in a model pathway containing BRCA1 and BRCA2 greatly increase risks for a subset of leukemias and lymphomas.[10]

Women who have inherited a defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are at a greatly elevated risk to develop breast and ovarian cancer. Their risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer is so high, and so specific to those cancers, that many mutation carriers choose to have prophylactic surgery. There has been much conjecture to explain such apparently striking tissue specificity. Major determinants of where BRCA1/2 hereditary cancers occur are related to tissue specificity of the cancer pathogen, the agent that causes chronic inflammation or the carcinogen. The target tissue may have receptors for the pathogen, may become selectively exposed to an inflammatory process or to a carcinogen. An innate genomic deficit in a tumor suppressor gene impairs normal responses and exacerbates the susceptibility to disease in organ targets. This theory also fits data for several tumor suppressors beyond BRCA1 or BRCA2. A major advantage of this model is that it suggests there may be some options in addition to prophylactic surgery.[58]

As aforementioned, biallelic and homozygous inheritance of the BRCA1 gene leads to FA-S, which is almost always an embryonically lethal condition.

Low expression of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancers

BRCA1 expression is reduced or undetectable in the majority of high grade, ductal breast cancers.[59] It has long been noted that loss of BRCA1 activity, either by germ-line mutations or by down-regulation of gene expression, leads to tumor formation in specific target tissues. In particular, decreased BRCA1 expression contributes to both sporadic and inherited breast tumor progression.[60] Reduced expression of BRCA1 is tumorigenic because it plays an important role in the repair of DNA damages, especially double-strand breaks, by the potentially error-free pathway of homologous recombination.[61] Since cells that lack the BRCA1 protein tend to repair DNA damages by alternative more error-prone mechanisms, the reduction or silencing of this protein generates mutations and gross chromosomal rearrangements that can lead to progression to breast cancer.[61]

Similarly, BRCA1 expression is low in the majority (55%) of sporadic epithelial ovarian cancers (EOCs) where EOCs are the most common type of ovarian cancer, representing approximately 90% of ovarian cancers.[62] In serous ovarian carcinomas, a sub-category constituting about 2/3 of EOCs, low BRCA1 expression occurs in more than 50% of cases.[63] Bowtell[64] reviewed the literature indicating that deficient homologous recombination repair caused by BRCA1 deficiency is tumorigenic. In particular this deficiency initiates a cascade of molecular events that sculpt the evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer and dictate its response to therapy. Especially noted was that BRCA1 deficiency could be the cause of tumorigenesis whether due to BRCA1 mutation or any other event that causes a deficiency of BRCA1 expression.

Mutation of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancer

Only about 3%–8% of all women with breast cancer carry a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2.[65] Similarly, BRCA1 mutations are only seen in about 18% of ovarian cancers (13% germline mutations and 5% somatic mutations).[66]

Thus, while BRCA1 expression is low in the majority of these cancers, BRCA1 mutation is not a major cause of reduced expression. Certain latent viruses, which are frequently detected in breast cancer tumors, can decrease the expression of the BRCA1 gene and cause the development of breast tumors.[67]

BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation in breast and ovarian cancer

BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation was present in only 13% of unselected primary breast carcinomas.[68] Similarly, BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation was present in only 5% to 15% of EOC cases.[62]

Thus, while BRCA1 expression is low in these cancers, BRCA1 promoter methylation is only a minor cause of reduced expression.

MicroRNA repression of BRCA1 in breast cancers

There are a number of specific microRNAs, when overexpressed, that directly reduce expression of specific DNA repair proteins (see MicroRNA section DNA repair and cancer) In the case of breast cancer, microRNA-182 (miR-182) specifically targets BRCA1.[69] Breast cancers can be classified based on receptor status or histology, with triple-negative breast cancer (15%–25% of breast cancers), HER2+ (15%–30% of breast cancers), ER+/PR+ (about 70% of breast cancers), and Invasive lobular carcinoma (about 5%–10% of invasive breast cancer). All four types of breast cancer were found to have an average of about 100-fold increase in miR-182, compared to normal breast tissue.[70] In breast cancer cell lines, there is an inverse correlation of BRCA1 protein levels with miR-182 expression.[69] Thus it appears that much of the reduction or absence of BRCA1 in high grade ductal breast cancers may be due to over-expressed miR-182.

In addition to miR-182, a pair of almost identical microRNAs, miR-146a and miR-146b-5p, also repress BRCA1 expression. These two microRNAs are over-expressed in triple-negative tumors and their over-expression results in BRCA1 inactivation.[71] Thus, miR-146a and/or miR-146b-5p may also contribute to reduced expression of BRCA1 in these triple-negative breast cancers.

MicroRNA repression of BRCA1 in ovarian cancers

In both serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (the precursor lesion to high grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HG-SOC)), and in HG-SOC itself, miR-182 is overexpressed in about 70% of cases.[72] In cells with over-expressed miR-182, BRCA1 remained low, even after exposure to ionizing radiation (which normally raises BRCA1 expression).[72] Thus much of the reduced or absent BRCA1 in HG-SOC may be due to over-expressed miR-182.

Another microRNA known to reduce expression of BRCA1 in ovarian cancer cells is miR-9.[62] Among 58 tumors from patients with stage IIIC or stage IV serous ovarian cancers (HG-SOG), an inverse correlation was found between expressions of miR-9 and BRCA1,[62] so that increased miR-9 may also contribute to reduced expression of BRCA1 in these ovarian cancers.

Deficiency of BRCA1 expression is likely tumorigenic

DNA damage appears to be the primary underlying cause of cancer,[73] and deficiencies in DNA repair appears to underlie many forms of cancer.[74] If DNA repair is deficient, DNA damage tends to accumulate. Such excess DNA damage may increase mutational errors during DNA replication due to error-prone translesion synthesis. Excess DNA damage may also increase epigenetic alterations due to errors during DNA repair.[75][76] Such mutations and epigenetic alterations may give rise to cancer. The frequent microRNA-induced deficiency of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancers likely contribute to the progression of those cancers.

Germ-line mutations and founder effect

All germ-line BRCA1 mutations identified to date have been inherited, suggesting the possibility of a large "founder" effect in which a certain mutation is common to a well-defined population group and can, in theory, be traced back to a common ancestor. Given the complexity of mutation screening for BRCA1, these common mutations may simplify the methods required for mutation screening in certain populations. Analysis of mutations that occur with high frequency also permits the study of their clinical expression.[77] Examples of manifestations of a founder effect are seen among Ashkenazi Jews. Three mutations in BRCA1 have been reported to account for the majority of Ashkenazi Jewish patients with inherited BRCA1-related breast and/or ovarian cancer: 185delAG, 188del11 and 5382insC in the BRCA1 gene.[78][79] In fact, it has been shown that if a Jewish woman does not carry a BRCA1 185delAG, BRCA1 5382insC founder mutation, it is highly unlikely that a different BRCA1 mutation will be found.[80] Additional examples of founder mutations in BRCA1 are given in Table 1 (mainly derived from[77]).

| Population or subgroup | BRCA1 mutation(s)[81] | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| African-Americans | 943ins10, M1775R | [82] |

| Afrikaners | E881X, 1374delC | [83][84] |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 185delAG, 188del11, 5382insC | [78][79] |

| Austrians | 2795delA, C61G, 5382insC, Q1806stop | [85] |

| Belgians | 2804delAA, IVS5+3A>G | [86][87] |

| Dutch | Exon 2 deletion, exon 13 deletion, 2804delAA | [86][88][89] |

| Finns | 3745delT, IVS11-2A>G | [90][91] |

| French | 3600del11, G1710X | [92] |

| French Canadians | C4446T | [93] |

| Germans | 5382insC, 4184del4 | [94][95] |

| Greeks | 5382insC | [96] |

| Hungarians | 300T>G, 5382insC, 185delAG | [97] |

| Italians | 5083del19 | [98] |

| Japanese | L63X, Q934X | [99] |

| Native North Americans | 1510insG, 1506A>G | [100] |

| Northern Irish | 2800delAA | [101] |

| Norwegians | 816delGT, 1135insA, 1675delA, 3347delAG | [102][103] |

| Pakistanis | 2080insA, 3889delAG, 4184del4, 4284delAG, IVS14-1A>G | [104] |

| Poles | 300T>G, 5382insC, C61G, 4153delA | [105][106] |

| Russians | 5382insC, 4153delA | [107] |

| Scots | 2800delAA | [101][108] |

| Spaniards | R71G | [109][110] |

| Swedes | Q563X, 3171ins5, 1201del11, 2594delC | [82][111] |

Female fertility

As women age, reproductive performance declines, leading to menopause. This decline is tied to a reduction in the number of ovarian follicles. Although about 1 million oocytes are present at birth in the human ovary, only about 500 (about 0.05%) of these ovulate. The decline in ovarian reserve appears to occur at a constantly increasing rate with age,[112] and leads to nearly complete exhaustion of the reserve by about age 52. As ovarian reserve and fertility decline with age, there is also a parallel increase in pregnancy failure and meiotic errors, resulting in chromosomally abnormal conceptions.[113]

Women with a germ-line BRCA1 mutation appear to have a diminished oocyte reserve and decreased fertility compared to normally aging women.[114] Furthermore, women with an inherited BRCA1 mutation undergo menopause prematurely.[115] Since BRCA1 is a key DNA repair protein, these findings suggest that naturally occurring DNA damages in oocytes are repaired less efficiently in women with a BRCA1 defect, and that this repair inefficiency leads to early reproductive failure.[114]

As noted above, the BRCA1 protein plays a key role in homologous recombinational repair. This is the only known cellular process that can accurately repair DNA double-strand breaks. DNA double-strand breaks accumulate with age in humans and mice in primordial follicles.[116] Primordial follicles contain oocytes that are at an intermediate (prophase I) stage of meiosis. Meiosis is the general process in eukaryotic organisms by which germ cells are formed, and it is likely an adaptation for removing DNA damages, especially double-strand breaks, from germ line DNA.[117] (Also see article Meiosis). Homologous recombinational repair employing BRCA1 is especially promoted during meiosis. It was found that expression of four key genes necessary for homologous recombinational repair of DNA double-strand breaks (BRCA1, MRE11, RAD51 and ATM) decline with age in the oocytes of humans and mice,[116] leading to the hypothesis that DNA double-strand break repair is necessary for the maintenance of oocyte reserve and that a decline in efficiency of repair with age plays a role in ovarian aging.

Cancer chemotherapy

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. At diagnosis, almost 70% of persons with NSCLC have locally advanced or metastatic disease. Persons with NSCLC are often treated with therapeutic platinum compounds (e.g. cisplatin, carboplatin or oxaliplatin) that cause inter-strand cross-links in DNA. Among individuals with NSCLC, low expression of BRCA1 in the primary tumor correlated with improved survival after platinum-containing chemotherapy.[118][119] This correlation implies that low BRCA1 in cancer, and the consequent low level of DNA repair, causes vulnerability of cancer to treatment by the DNA cross-linking agents. High BRCA1 may protect cancer cells by acting in a pathway that removes the damages in DNA introduced by the platinum drugs. Thus the level of BRCA1 expression is a potentially important tool for tailoring chemotherapy in lung cancer management.[118][119]

Level of BRCA1 expression is also relevant to ovarian cancer treatment. Patients having sporadic ovarian cancer who were treated with platinum drugs had longer median survival times if their BRCA1 expression was low compared to patients with higher BRCA1 expression (46 compared to 33 months).[120]

Patents, enforcement, litigation, and controversy

A patent application for the isolated BRCA1 gene and cancer promoting mutations discussed above, as well as methods to diagnose the likelihood of getting breast cancer, was filed by the University of Utah, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and Myriad Genetics in 1994;[14] over the next year, Myriad, (in collaboration with investigators at Endo Recherche, Inc., HSC Research & Development Limited Partnership, and University of Pennsylvania), isolated and sequenced the BRCA2 gene and identified key mutations, and the first BRCA2 patent was filed in the U.S. by Myriad and other institutions in 1995.[15] Myriad is the exclusive licensee of these patents and has enforced them in the US against clinical diagnostic labs.[17] This business model led from Myriad being a startup in 1994 to being a publicly traded company with 1200 employees and about $500M in annual revenue in 2012;[16] it also led to controversy over high prices and the inability to get second opinions from other diagnostic labs, which in turn led to the landmark Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics lawsuit.[17][121] The patents began to expire in 2014.

According to an article published in the journal, Genetic Medicine, in 2010, "The patent story outside the United States is more complicated.... For example, patents have been obtained but the patents are being ignored by provincial health systems in Canada. In Australia and the UK, Myriad's licensee permitted use by health systems but announced a change of plans in August 2008. Only a single mutation has been patented in Myriad's lone European-wide patent, although some patents remain under review of an opposition proceeding. In effect, the United States is the only jurisdiction where Myriad's strong patent position has conferred sole-provider status."[122][123] Peter Meldrum, CEO of Myriad Genetics, has acknowledged that Myriad has "other competitive advantages that may make such [patent] enforcement unnecessary" in Europe.[124]

As with any gene, finding variation in BRCA1 is not hard. The real value comes from understanding what the clinical consequences of any particular variant are. Myriad has a large, proprietary database of such genotype-phenotype correlations. In response, parallel open-source databases are being developed.

Legal decisions surrounding the BRCA1 and BRCA2 patents will affect the field of genetic testing in general.[125] A June 2013 article, in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics (No. 12-398), quoted the US Supreme Court's unanimous ruling that, "A naturally occurring DNA segment is a product of nature and not patent eligible merely because it has been isolated," invalidating Myriad's patents on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. However, the Court also held that manipulation of a gene to create something not found in nature could still be eligible for patent protection.[126] The Federal Court of Australia came to the opposite conclusion, upholding the validity of an Australian Myriad Genetics patent over the BRCA1 gene in February 2013.[127] The Federal Court also rejected an appeal in September 2014.[128] Yvonne D'Arcy won her case against US-based biotech company Myriad Genetics in the High Court of Australia. In their unanimous decision on October 7, 2015, the "high court found that an isolated nucleic acid, coding for a BRCA1 protein, with specific variations from the norm that are indicative of susceptibility to breast cancer and ovarian cancer was not a 'patentable invention.'"[129]

Interactions

BRCA1 has been shown to interact with the following proteins:

- ABL1[130]

- AKT1[131][132]

- AR[133]

- ATR[134][135][136][137]

- ATM[12][134][135][136][137][138][139]

- ATF1[140]

- BACH1[141]

- BARD1[26][36][40][141]

- BRCA2[142][143][144][145]

- BRCC3[142]

- BRE[142]

- BRIP1[30][146][147][148][149][150]

- C-jun[151]

- CHEK2[152][153]

- CLSPN[154]

- COBRA1[155]

- CREBBP[156][157][158][159][160]

- CSNK2B[161]

- CSTF2[162][163]

- CDK2[164][165][166]

- DHX9[167][168]

- ELK4[169]

- EP300[157][159]

- ESR1[159][170][171][172]

- FANCA[173]

- FANCD2[174][144]

- FHL2[175][176]

- H2AFX[177][178][179]

- JUNB[151]

- JunD[151]

- LMO4[180][181]

- MAP3K3[182]

- MED1[147]

- MED17[183][147][184]

- MED21[185]

- MED24[147]

- MRE11A[12][183][186][187]

- MSH2[12][36]

- MSH3[36][146]

- MSH6[12][36]

- Myc[40][188][189][190]

- NBN[12][183][186]

- NMI[188]

- NPM1[191]

- NCOA2[146][192]

- NUFIP1[193]

- P53[142][158][194][195][196]

- PALB2[197]

- POLR2A[183][185][198][199]

- PPP1CA[200]

- Rad50[12][183][186]

- RAD51[36][142][143][201]

- RBBP4[202]

- RBBP7[202][203][204]

- RBBP8[205][146][206][207][208][209][210]

- RELA[156]

- RB1[202][211][212]

- RBL1[211]

- RBL2[211]

- RPL31[204]

- SMARCA4[213][214]

- SMARCB1[213]

- STAT1[215]

- TOPBP1[216]

- UBE2D1[177][217][218][219][178][142][191][174][220][221]

- USF2[222]

- VCP[223]

- XIST[224][225]

- ZNF350[226]

References

- ↑ "BRCA1 and BRCA2: No Longer the Only Troublesome Genes Out There". HealthCentral. 2007-05-29. https://www.healthcentral.com/breast-cancer/c/78/9925/brca1-brca2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "BRCA1 gene tree". Ensembl. https://www.ensembl.org/Multi/GeneTree/Image?gt=ENSGT00440000034289.

- ↑ "BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins: roles in health and disease". Molecular Pathology 51 (5): 237–47. October 1998. doi:10.1136/mp.51.5.237. PMID 10193517.

- ↑ "Role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 as regulators of DNA repair, transcription, and cell cycle in response to DNA damage". Cancer Science 95 (11): 866–71. November 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02195.x. PMID 15546503.

- ↑ "BRCA: What we know now". College of American Pathologists. September 2006. https://www.cap.org/apps/cap.portal?_nfpb=true&cntvwrPtlt_actionOverride=%2Fportlets%2FcontentViewer%2Fshow&_windowLabel=cntvwrPtlt&cntvwrPtlt{actionForm.contentReference}=cap_today%2Ffeature_stories%2F0906BRCA.html&_state=maximized&_pageLabel=cntvwr.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "New concepts on BARD1: Regulator of BRCA pathways and beyond". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 72: 1–17. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2015.12.008. PMID 26738429.

- ↑ "The BRCA1/2 pathway prevents hematologic cancers in addition to breast and ovarian cancers". BMC Cancer 7: 152–162. August 2007. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-152. PMID 17683622.

- ↑ "Breast cancer genes protect against some leukemias and lymphomas" (video). SciVee. 2008-06-08. https://www.scivee.tv/node/6090.

- ↑ "Breast and Ovarian Cancer Genetic Screening". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. https://www.pamf.org/health/guidelines/geneticscreening.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "The BRCA1/2 pathway prevents hematologic cancers in addition to breast and ovarian cancers". BMC Cancer 7: 152. 2007. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-152. PMID 17683622.

- ↑ "BRCA1 and BRCA2: breast/ovarian cancer susceptibility gene products and participants in DNA double-strand break repair". Carcinogenesis 31 (6): 961–7. April 2010. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq069. PMID 20400477.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 "BASC, a super complex of BRCA1-associated proteins involved in the recognition and repair of aberrant DNA structures". Genes Dev. 14 (8): 927–39. April 2000. doi:10.1101/gad.14.8.927. PMID 10783165.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The multiple nuclear functions of BRCA1: transcription, ubiquitination and DNA repair". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 15 (3): 345–350. 2003. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00042-5. PMID 12787778.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Skolnick HS, Goldgar DE, Miki Y, Swenson J, Kamb A, Harshman KD, Shattuck-Eidens DM, Tavtigian SV, Wiseman RW, Futreal PA, "7Q-linked breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene", US patent 5747282, issued 1998-05-05, assigned to Myriad Genetics, Inc., The United States of America as represented by the Secretary of Health and Human Services,and University of Utah Research Foundation

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Tavtigian SV, Kamb A, Simard J, Couch F, Rommens JM, Weber BL, "Chromosome 13-linked breast cancer susceptibility gene", US patent 5837492, issued 1998-11-17, assigned to Myriad Genetics, Inc., Endo Recherche, Inc., HSC Research & Development Limited Partnership, Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Myriad Investor Page—see "Myriad at a glance" accessed October 2012

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Cancer Patients Challenge the Patenting of a Gene". The New York Times. 2009-05-12. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/13/health/13patent.html.

- ↑ "Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21". Science 250 (4988): 1684–9. December 1990. doi:10.1126/science.2270482. PMID 2270482. Bibcode: 1990Sci...250.1684H.

- ↑ High-Impact Science: Tracking down the BRCA genes (Part 1) – Cancer Research UK science blog, 2012

- ↑ "A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1". Science 266 (5182): 66–71. October 1994. doi:10.1126/science.7545954. PMID 7545954. Bibcode: 1994Sci...266...66M.

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine EntrezGene reference information for BRCA1 breast cancer 1, early onset (Homo sapiens)

- ↑ "BRCA1: a review of structure and putative functions". Dis. Markers 13 (4): 261–74. February 1998. doi:10.1155/1998/298530. PMID 9553742.

- ↑ "Regulation of BRCA1, BRCA2 and BARD1 intracellular trafficking". BioEssays 27 (9): 884–93. September 2005. doi:10.1002/bies.20277. PMID 16108063.

- ↑ Universal protein resource accession number P38398 for "Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein" at UniProt.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Structure-Function Of The Tumor Suppressor BRCA1". Comput Struct Biotechnol J 1 (1): e201204005. April 2012. doi:10.5936/csbj.201204005. PMID 22737296.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "Structure of a BRCA1-BARD1 heterodimeric RING-RING complex". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 8 (10): 833–7. October 2001. doi:10.1038/nsb1001-833. PMID 11573085.

- ↑ "With the ends in sight: images from the BRCA1 tumor suppressor". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 8 (10): 822–4. October 2001. doi:10.1038/nsb1001-822. PMID 11573079.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Crystal structure of the BRCT repeat region from the breast cancer-associated protein BRCA1". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 8 (10): 838–42. October 2001. doi:10.1038/nsb1001-838. PMID 11573086.

- ↑ "The BRCA1 C-terminal domain: structure and function". Mutat. Res. 460 (3–4): 319–32. August 2000. doi:10.1016/S0921-8777(00)00034-3. PMID 10946236.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Structure of the 53BP1 BRCT region bound to p53 and its comparison to the Brca1 BRCT structure". Genes Dev. 16 (5): 583–93. March 2002. doi:10.1101/gad.959202. PMID 11877378.

- ↑ "Biallelic Mutations in BRCA1 Cause a New Fanconi Anemia Subtype". Cancer Discov 5 (2): 135–42. 2014. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1156. PMID 25472942.

- ↑ "Kimball's Biologh Pages". https://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/D/DNArepair.html#DSBs.

- ↑ "Biallelic deleterious BRCA1 mutations in a woman with early-onset ovarian cancer". Cancer Discovery 3 (4): 399–405. April 2013. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0421. PMID 23269703.

- ↑ "Cellular functions of the BRCA tumour-suppressor proteins". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34 (Pt 5): 633–45. November 2006. doi:10.1042/BST0340633. PMID 17052168.

- ↑ Roy, Rohini; Chun, Jarin; Powell, Simon N. (January 2012). "BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection" (in en). Nature Reviews Cancer 12 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1038/nrc3181. ISSN 1474-175X. PMID 22193408.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 "Adenosine nucleotide modulates the physical interaction between hMSH2 and BRCA1". Oncogene 20 (34): 4640–9. August 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204625. PMID 11498787.

- ↑ "Proteomics of mouse BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors identifies DNA repair proteins with potential diagnostic and prognostic value in human breast cancer". Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11 (7): M111.013334-1-M111.013334-19. July 2012. doi:10.1074/mcp.M111.013334. PMID 22366898.

- ↑ "The ubiquitin-selective segregase VCP/p97 orchestrates the response to DNA double-strand breaks". Nat. Cell Biol. 13 (11): 1376–82. November 2011. doi:10.1038/ncb2367. PMID 22020440.

- ↑ "VCP, a weak ATPase involved in multiple cellular events, interacts physically with BRCA1 in the nucleus of living cells". DNA Cell Biol 19 (5): 253–263. 2000. doi:10.1089/10445490050021168. PMID 10855792.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "BRCA1 binds c-Myc and inhibits its transcriptional and transforming activity in cells". Oncogene 17 (15): 1939–48. October 1998. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202403. PMID 9788437.

- ↑ "Direct DNA binding by Brca1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (11): 6086–6091. 2001. doi:10.1073/pnas.111125998. PMID 11353843.

- ↑ "Good timing in the cell cycle for precise DNA repair by BRCA1". Cell Cycle 4 (9): 1216–22. 2005. doi:10.4161/cc.4.9.2027. PMID 16103751.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 "BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations". The Journal of Cell Biology 155 (6): 911–922. 2001. doi:10.1083/jcb.200108049. PMID 11739404.

- ↑ "Cells deficient in the FANC/BRCA pathway are hypersensitive to plasma levels of formaldehyde". Cancer Res. 67 (23): 11117–22. December 2007. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3028. PMID 18056434.

- ↑ "Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 7 (4): a016600. April 2015. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016600. PMID 25833843.

- ↑ "BRCA1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94 (11): 5605–10. 1997. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.11.5605. PMID 9159119. Bibcode: 1997PNAS...94.5605S.

- ↑ "BRCA1 Is Associated with a Human SWI/SNF-Related Complex Linking Chromatin Remodeling to Breast Cancer". Cell 102 (2): 257–265. 2000. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00030-1. PMID 10943845.

- ↑ "BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer". GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. December 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/.

- ↑ "Genetics". Breastcancer.org. 2012-09-17. https://www.breastcancer.org/risk/factors/genetics.

- ↑ "BRCA1 mutation analysis of 41 human breast cancer cell lines reveals three new deleterious mutants". Cancer Research 66 (1): 41–45. January 2006. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2853. PMID 16397213.

- ↑ "Genomic rearrangements in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes". Hum. Mutat. 25 (5): 415–22. May 2005. doi:10.1002/humu.20169. PMID 15832305.

- ↑ "Real-time PCR-based gene dosage assay for detecting BRCA1 rearrangements in breast-ovarian cancer families". Clin. Genet. 65 (2): 131–6. February 2004. doi:10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00200.x. PMID 14984472.

- ↑ "Large genomic deletions and duplications in the BRCA1 gene identified by a novel quantitative method". Cancer Res. 63 (7): 1449–53. April 2003. PMID 12670888.

- ↑ "Rapid detection of novel BRCA1 rearrangements in high-risk breast-ovarian cancer families using multiplex PCR of short fluorescent fragments". Hum. Mutat. 20 (3): 218–26. September 2002. doi:10.1002/humu.10108. PMID 12203994.

- ↑ "High-resolution oligonucleotide array-CGH applied to the detection and characterization of large rearrangements in the hereditary breast cancer gene BRCA1". Clin. Genet. 72 (3): 199–207. September 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00849.x. PMID 17718857.

- ↑ "Promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 correlates with absence of expression in hereditary breast cancer tumors". Epigenetics 3 (3): 157–63. 2008. doi:10.4161/epi.3.3.6387. PMID 18567944.

- ↑ "Novel genetic variants in microRNA genes and familial breast cancer". Int. J. Cancer 124 (5): 1178–82. March 2009. doi:10.1002/ijc.24008. PMID 19048628.

- ↑ "Evidence that BRCA1- or BRCA2-associated cancers are not inevitable". Mol Med 18 (9): 1327–37. 2012. doi:10.2119/molmed.2012.00280. PMID 22972572.

- ↑ "Localization of human BRCA1 and its loss in high-grade, non-inherited breast carcinomas". Nat. Genet. 21 (2): 236–40. 1999. doi:10.1038/6029. PMID 9988281.

- ↑ "Regulation of BRCA1 expression and its relationship to sporadic breast cancer". Breast Cancer Res. 5 (1): 45–52. 2003. doi:10.1186/bcr557. PMID 12559046.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer". Mutagenesis 22 (4): 247–53. 2007. doi:10.1093/mutage/gem009. PMID 17412712.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 "miR-9 regulation of BRCA1 and ovarian cancer sensitivity to cisplatin and PARP inhibition". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 105 (22): 1750–8. 2013. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt302. PMID 24168967.

- ↑ "Expression analysis of MIR182 and its associated target genes in advanced ovarian carcinoma". Mod. Pathol. 25 (12): 1644–53. 2012. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.118. PMID 22790015.

- ↑ "The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer". Nat. Rev. Cancer 10 (11): 803–8. 2010. doi:10.1038/nrc2946. PMID 20944665.

- ↑ "Breast cancer susceptibility genes. BRCA1 and BRCA2". Medicine (Baltimore) 77 (3): 208–26. 1998. doi:10.1097/00005792-199805000-00006. PMID 9653432.

- ↑ "Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas". Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (3): 764–75. 2014. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287. PMID 24240112.

- ↑ "How latent viruses cause breast cancer: An explanation based on the microcompetition model". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 19 (3): 221–226. August 2019. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2018.3950. PMID 30579323.

- ↑ "Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92 (7): 564–9. 2000. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.7.564. PMID 10749912.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "miR-182-mediated downregulation of BRCA1 impacts DNA repair and sensitivity to PARP inhibitors". Mol. Cell 41 (2): 210–20. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.005. PMID 21195000.

- ↑ "MicroRNA-182-5p targets a network of genes involved in DNA repair". RNA 19 (2): 230–42. 2013. doi:10.1261/rna.034926.112. PMID 23249749.

- ↑ "Down-regulation of BRCA1 expression by miR-146a and miR-146b-5p in triple negative sporadic breast cancers". EMBO Mol Med 3 (5): 279–90. 2011. doi:10.1002/emmm.201100136. PMID 21472990.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "MiR-182 overexpression in tumourigenesis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma". J. Pathol. 228 (2): 204–15. 2012. doi:10.1002/path.4000. PMID 22322863.

- ↑ "DNA damage responses: mechanisms and roles in human disease: 2007 G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture". Mol. Cancer Res. 6 (4): 517–24. 2008. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0020. PMID 18403632.

- ↑ "The DNA damage response: ten years after". Mol. Cell 28 (5): 739–45. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. PMID 18082599.

- ↑ "Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island". PLOS Genetics 4 (8): e1000155. 2008. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155. PMID 18704159.

- ↑ "DNA damage, homology-directed repair, and DNA methylation". PLOS Genetics 3 (7): e110. Jul 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030110. PMID 17616978.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "The "portrait" of hereditary breast cancer". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 89 (3): 297–304. 2005. doi:10.1007/s10549-004-2172-4. PMID 15754129.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "The carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals". Nat. Genet. 11 (2): 198–200. October 1995. doi:10.1038/ng1095-198. PMID 7550349.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "BRCA1 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish women". American Journal of Human Genetics 57 (1): 189. 1995. PMID 7611288.

- ↑ "BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond". Nature Reviews Cancer 4 (9): 665–676. 2004. doi:10.1038/nrc1431. PMID 15343273.

- ↑ "Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion". Human Mutation 15 (1): 7–12. 2000. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10612815.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "Founder populations and their uses for breast cancer genetics". Cancer Research 2 (2): 77–81. 2000. doi:10.1186/bcr36. PMID 11250694.

- ↑ "BRCA1 mutations in South African breast and/or ovarian cancer families: evidence of a novel founder mutation in Afrikaner families". Int. J. Cancer 110 (5): 677–82. July 2004. doi:10.1002/ijc.20186. PMID 15146556.

- ↑ "BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 mutations and CHEK2 c.1100delC in different South African ethnic groups diagnosed with premenopausal and/or triple negative breast cancer". BMC Cancer 15: 912. Nov 2015. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1913-6. PMID 26577449.

- ↑ "BRCA1-related breast cancer in Austrian breast and ovarian cancer families: specific BRCA1 mutations and pathological characteristics". International Journal of Cancer 77 (3): 354–360. 1998. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980729)77:3<354::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 9663595.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 "A high proportion of novel mutations in BRCA1 with strong founder effects among Dutch and Belgian hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families". American Journal of Human Genetics 60 (5): 1041–1049. 1997. PMID 9150151.

- ↑ "Mutation analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in the Belgian patient population and identification of a Belgian founder mutation BRCA1 IVS5 + 3A > G". Disease Markers 15 (1–3): 69–73. 1999. doi:10.1155/1999/241046. PMID 10595255.

- ↑ "BRCA1 genomic deletions are major founder mutations in Dutch breast cancer patients". Nature Genetics 17 (3): 341–345. 1997. doi:10.1038/ng1197-341. PMID 9354803. https://repub.eur.nl/pub/54808/ng1197-341.pdf.

- ↑ "Large regional differences in the frequency of distinct BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in 517 Dutch breast and/or ovarian cancer families". European Journal of Cancer 37 (16): 2082–2090. 2001. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00244-1. PMID 11597388.

- ↑ "Evidence of founder mutations in Finnish BRCA1 and BRCA2 families". American Journal of Human Genetics 62 (6): 1544–1548. 1998. doi:10.1086/301880. PMID 9585608.

- ↑ "Involvement of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast cancer in a western Finnish sub-population". Genetic Epidemiology 20 (2): 239–246. 2001. doi:10.1002/1098-2272(200102)20:2<239::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 11180449.

- ↑ "BRCA1 testing in breast and/or ovarian cancer families from northeastern France identifies two common mutations with a founder effect". Familial Cancer 3 (1): 15–20. 2004. doi:10.1023/B:FAME.0000026819.44213.df. PMID 15131401.

- ↑ "Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in French Canadian ovarian cancer cases unselected for family history". Clinical Genetics 55 (5): 318–324. 1999. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550504.x. PMID 10422801.

- ↑ "Frequency of BRCA1 mutation 5382insC in German breast cancer patients". Gynecologic Oncology 72 (3): 402–406. 1999. doi:10.1006/gyno.1998.5270. PMID 10053113.

- ↑ "Mutation data of the BRCA1 gene". KMDB/MutationView (Keio Mutation Databases). Keio University. https://mutview.dmb.med.keio.ac.jp/MutationView/jsp/mutview/html/brca1.html.

- ↑ "Germ line BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Greek breast/ovarian cancer families: 5382insC is the most frequent mutation observed". Cancer Letters 185 (1): 61–70. 2002. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00845-X. PMID 12142080.

- ↑ "Prevalence of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among breast and ovarian cancer patients in Hungary". International Journal of Cancer 86 (5): 737–740. 2000. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<737::AID-IJC21>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 10797299.

- ↑ "Evidence of a founder mutation of BRCA1 in a highly homogeneous population from southern Italy with breast/ovarian cancer". Human Mutation 18 (2): 163–164. 2001. doi:10.1002/humu.1167. PMID 11462242.

- ↑ "Mutational analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and clinicopathologic analysis of ovarian cancer in 82 ovarian cancer families: two common founder mutations of BRCA1 in Japanese population". Clinical Cancer Research 7 (10): 3144–3150. 2001. PMID 11595708.

- ↑ "A BRCA1 mutation in Native North American families". Human Mutation 19 (4): 460. 2002. doi:10.1002/humu.9027. PMID 11933205.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 The Scottish/Northern Irish BRCA1/BRCA2 Consortium (2003). "BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Scotland and Northern Ireland". British Journal of Cancer 88 (8): 1256–1262. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600840. PMID 12698193.

- ↑ "BRCA1 1675delA and 1135insA account for one third of Norwegian familial breast-ovarian cancer and are associated with later disease onset than less frequent mutations". Disease Markers 15 (1–3): 79–84. 1999. doi:10.1155/1999/278269. PMID 10595257.

- ↑ "The Norwegian founder mutations in BRCA1: high penetrance confirmed in an incident cancer series and differences observed in the risk of ovarian cancer". European Journal of Cancer 39 (15): 2205–2213. 2003. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00548-3. PMID 14522380.

- ↑ "Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations to Breast and Ovarian Cancer in Pakistan". American Journal of Human Genetics 71 (3): 595–606. 2002. doi:10.1086/342506. PMID 12181777.

- ↑ "Founder mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Polish families with breast-ovarian cancer". American Journal of Human Genetics 66 (6): 1963–1968. 2000. doi:10.1086/302922. PMID 10788334.

- ↑ "BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis in breast-ovarian cancer families from northeastern Poland". Hum. Mutat. 21 (5): 553–4. May 2003. doi:10.1002/humu.9139. PMID 12673801.

- ↑ "Frequently occurring germ-line mutations of the BRCA1 gene in ovarian cancer families from Russia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60 (5): 1239–42. May 1997. PMID 9150173.

- ↑ "Evidence of a founder BRCA1 mutation in Scotland". Br. J. Cancer 82 (3): 705–11. February 2000. doi:10.1054/bjoc.1999.0984. PMID 10682686.

- ↑ "The R71G BRCA1 is a founder Spanish mutation and leads to aberrant splicing of the transcript". Hum. Mutat. 17 (6): 520–1. June 2001. doi:10.1002/humu.1136. PMID 11385711.

- ↑ "Haplotype analysis of the BRCA2 9254delATCAT recurrent mutation in breast/ovarian cancer families from Spain". Hum. Mutat. 21 (4): 452. April 2003. doi:10.1002/humu.9133. PMID 12655574.

- ↑ "The western Swedish BRCA1 founder mutation 3171ins5; a 3.7 cM conserved haplotype of today is a reminiscence of a 1500-year-old mutation". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 9 (10): 787–93. October 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200704. PMID 11781691.

- ↑ "A new model of reproductive aging: the decline in ovarian non-growing follicle number from birth to menopause". Hum. Reprod. 23 (3): 699–708. March 2008. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem408. PMID 18192670.

- ↑ "Maternal age and chromosomally abnormal pregnancies: what we know and what we wish we knew". Current Opinion in Pediatrics 21 (6): 703–8. December 2009. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e328332c6ab. PMID 19881348.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 "Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian insufficiency: a possible explanation for the link between infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks". J. Clin. Oncol. 28 (2): 240–4. January 2010. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2057. PMID 19996028.

- ↑ "Premature menopause in patients with BRCA1 gene mutation". Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 100 (1): 59–63. November 2006. doi:10.1007/s10549-006-9220-1. PMID 16773440.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans". Sci Transl Med 5 (172): 172ra21. February 2013. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925. PMID 23408054.

- ↑ Bernstein H; Hopf FA; Michod RE (1987). The Molecular Basis of the Evolution of Sex. Adv. Genet. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 24. pp. 323–70. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 9780120176243. PMID 3324702

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 "BRCA1 mRNA expression levels as an indicator of chemoresistance in lung cancer". Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 (20): 2443–9. October 2004. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh260. PMID 15317748.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 "ERCC1 and BRAC1 mRNA expression levels in the primary tumor could predict the effectiveness of the second-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy in pretreated patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer". J Thorac Oncol 7 (4): 663–71. April 2012. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318244bdd4. PMID 22425915.

- ↑ "The DNA repair proteins BRCA1 and ERCC1 as predictive markers in sporadic ovarian cancer". Int. J. Cancer 124 (4): 806–15. February 2009. doi:10.1002/ijc.23987. PMID 19035454.

- ↑ "ACLU sues over patents on breast cancer genes". CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/05/12/us.genes.lawsuit/index.html.

- ↑ "Impact of gene patents and licensing practices on access to genetic testing for inherited susceptibility to cancer: comparing breast and ovarian cancers with colon cancers". Genetics in Medicine 12 (4 Suppl): S15–S38. April 2010. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181d5a67b. PMID 20393305.

- ↑ "European groups oppose Myriad's latest patent on BRCA1". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95 (1): 8–9. January 2003. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.1.8. PMID 12509391.

- ↑ "How Will Myriad Respond to the Next Generation of BRCA Testing?". Robinson, Bradshaw, and Hinson. March 2011. https://www.genomicslawreport.com/index.php/2011/03/01/how-will-myriad-respond-to-the-next-generation-of-brca-testing/.

- ↑ "Genetics and Patenting". Human Genome Project Information. U.S. Department of Energy Genome Programs. 2010-07-07. https://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/patents.shtml.

- ↑ "Supreme Court Rules Human Genes May Not Be Patented". The New York Times. June 13, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/14/us/supreme-court-rules-human-genes-may-not-be-patented.html.

- ↑ "Landmark patent ruling over breast cancer gene BRCA1". Sydney Morning Herald. February 15, 2013. https://www.smh.com.au/national/health/landmark-patent-ruling-over-breast-cancer-gene-brca1-20130215-2egsq.html.

- ↑ "Australian federal court rules isolated genetic material can be patented". The Guardian. 5 September 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/05/court-rules-breast-cancer-gene-brca1-patented-australia.

- ↑ "Patient wins high court challenge against company's cancer gene patent". The Guardian. 7 October 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/oct/07/patient-wins-high-court-challenge-against-companys-cancer-gene-patent.

- ↑ "Constitutive association of BRCA1 and c-Abl and its ATM-dependent disruption after irradiation". Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 (12): 4020–32. June 2002. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.12.4020-4032.2002. PMID 12024016.

- ↑ "Heregulin induces phosphorylation of BRCA1 through phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/AKT in breast cancer cells". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (45): 32274–8. November 1999. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.45.32274. PMID 10542266.

- ↑ "Negative Regulation of AKT Activation by BRCA1". Cancer Res. 68 (24): 10040–4. December 2008. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3009. PMID 19074868.

- ↑ "Increase of androgen-induced cell death and androgen receptor transactivation by BRCA1 in prostate cancer cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (21): 11256–61. October 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.190353897. PMID 11016951. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9711256Y.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 "Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (53): 37538–43. December 1999. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. PMID 10608806.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Functional interactions between BRCA1 and the checkpoint kinase ATR during genotoxic stress". Genes Dev. 14 (23): 2989–3002. December 2000. doi:10.1101/gad.851000. PMID 11114888.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "Ataxia telangiectasia-related protein is involved in the phosphorylation of BRCA1 following deoxyribonucleic acid damage". Cancer Res. 60 (18): 5037–9. September 2000. PMID 11016625.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 "Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase and ATM and Rad3 related kinase mediate phosphorylation of Brca1 at distinct and overlapping sites. In vivo assessment using phospho-specific antibodies". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (20): 17276–80. May 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M011681200. PMID 11278964.

- ↑ "Role for ATM in DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of BRCA1". Cancer Res. 60 (12): 3299–304. June 2000. PMID 10866324.

- ↑ "Requirement of ATM-dependent phosphorylation of brca1 in the DNA damage response to double-strand breaks". Science 286 (5442): 1162–6. November 1999. doi:10.1126/science.286.5442.1162. PMID 10550055.

- ↑ "BRCA1 physically and functionally interacts with ATF1". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (46): 36230–7. November 2000. doi:10.1074/jbc.M002539200. PMID 10945975.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 "BACH1, a novel helicase-like protein, interacts directly with BRCA1 and contributes to its DNA repair function". Cell 105 (1): 149–60. April 2001. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00304-X. PMID 11301010.

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 142.2 142.3 142.4 142.5 "Regulation of BRCC, a holoenzyme complex containing BRCA1 and BRCA2, by a signalosome-like subunit and its role in DNA repair". Mol. Cell 12 (5): 1087–99. November 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00424-6. PMID 14636569.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 "Stable interaction between the products of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes in mitotic and meiotic cells". Mol. Cell 2 (3): 317–28. September 1998. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80276-2. PMID 9774970.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 "Yeast two-hybrid screens imply involvement of Fanconi anemia proteins in transcription regulation, cell signaling, oxidative metabolism, and cellular transport". Exp. Cell Res. 289 (2): 211–21. October 2003. doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00261-1. PMID 14499622.

- ↑ "Analysis of murine Brca2 reveals conservation of protein–protein interactions but differences in nuclear localization signals". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (40): 37640–8. October 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106281200. PMID 11477095.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 146.2 146.3 "Phosphopeptide binding specificities of BRCA1 COOH-terminal (BRCT) domains". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (52): 52914–8. December 2003. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300407200. PMID 14578343.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 147.2 147.3 "BRCA1 function mediates a TRAP/DRIP complex through direct interaction with TRAP220". Oncogene 23 (35): 6000–5. August 2004. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207786. PMID 15208681.

- ↑ "Structural basis of BACH1 phosphopeptide recognition by BRCA1 tandem BRCT domains". Structure 12 (7): 1137–46. July 2004. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.06.002. PMID 15242590.

- ↑ "The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain". Science 302 (5645): 639–42. October 2003. doi:10.1126/science.1088753. PMID 14576433. Bibcode: 2003Sci...302..639Y.

- ↑ "Structure and mechanism of BRCA1 BRCT domain recognition of phosphorylated BACH1 with implications for cancer". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 11 (6): 512–8. June 2004. doi:10.1038/nsmb775. PMID 15133502.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 151.2 "JunB potentiates function of BRCA1 activation domain 1 (AD1) through a coiled-coil-mediated interaction". Genes Dev. 16 (12): 1509–17. June 2002. doi:10.1101/gad.995502. PMID 12080089.

- ↑ "hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response". Nature 404 (6774): 201–4. March 2000. doi:10.1038/35004614. PMID 10724175. Bibcode: 2000Natur.404..201L.

- ↑ "BRCA1 is regulated by Chk2 in response to spindle damage". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783 (12): 2223–33. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.08.006. PMID 18804494.

- ↑ "Human Claspin works with BRCA1 to both positively and negatively regulate cell proliferation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (17): 6484–9. April 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401847101. PMID 15096610. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.6484L.

- ↑ "BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations". J. Cell Biol. 155 (6): 911–21. December 2001. doi:10.1083/jcb.200108049. PMID 11739404.

- ↑ 156.0 156.1 "BRCA1 augments transcription by the NF-kappaB transcription factor by binding to the Rel domain of the p65/RelA subunit". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (29): 26333–41. July 2003. doi:10.1074/jbc.M303076200. PMID 12700228.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 "CBP/p300 interact with and function as transcriptional coactivators of BRCA1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (3): 1020–5. February 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1020. PMID 10655477. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.1020P.

- ↑ 158.0 158.1 "The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter". Oncogene 18 (1): 263–8. January 1999. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202323. PMID 9926942.

- ↑ 159.0 159.1 159.2 "p300 Modulates the BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor activity". Cancer Res. 62 (1): 141–51. January 2002. PMID 11782371.

- ↑ "Factors associated with the mammalian RNA polymerase II holoenzyme". Nucleic Acids Res. 26 (3): 847–53. February 1998. doi:10.1093/nar/26.3.847. PMID 9443979.

- ↑ "Casein kinase 2 binds to and phosphorylates BRCA1". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260 (3): 658–64. July 1999. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0892. PMID 10403822.

- ↑ "The BARD1-CstF-50 interaction links mRNA 3' end formation to DNA damage and tumor suppression". Cell 104 (5): 743–53. March 2001. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00270-7. PMID 11257228.

- ↑ "Functional interaction of BRCA1-associated BARD1 with polyadenylation factor CstF-50". Science 285 (5433): 1576–9. September 1999. doi:10.1126/science.285.5433.1576. PMID 10477523.

- ↑ "BRCA1 proteins are transported to the nucleus in the absence of serum and splice variants BRCA1a, BRCA1b are tyrosine phosphoproteins that associate with E2F, cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases". Oncogene 15 (2): 143–57. Jul 1997. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201252. PMID 9244350.

- ↑ "BRCA1 is a 220-kDa nuclear phosphoprotein that is expressed and phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner". Cancer Res. 56 (14): 3168–72. July 1996. PMID 8764100.

- ↑ "BRCA1 is phosphorylated at serine 1497 in vivo at a cyclin-dependent kinase 2 phosphorylation site". Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (7): 4843–54. July 1999. doi:10.1128/MCB.19.7.4843. PMID 10373534.

- ↑ "Overexpression of a protein fragment of RNA helicase A causes inhibition of endogenous BRCA1 function and defects in ploidy and cytokinesis in mammary epithelial cells". Oncogene 22 (7): 983–91. February 2003. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206195. PMID 12592385.

- ↑ "BRCA1 protein is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex via RNA helicase A". Nat. Genet. 19 (3): 254–6. July 1998. doi:10.1038/930. PMID 9662397.

- ↑ "c-Fos oncogene regulator Elk-1 interacts with BRCA1 splice variants BRCA1a/1b and enhances BRCA1a/1b-mediated growth suppression in breast cancer cells". Oncogene 20 (11): 1357–67. March 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204256. PMID 11313879.

- ↑ "BRCA1 mediates ligand-independent transcriptional repression of the estrogen receptor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (17): 9587–92. August 2001. doi:10.1073/pnas.171174298. PMID 11493692. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...98.9587Z.

- ↑ "Role of direct interaction in BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor activity". Oncogene 20 (1): 77–87. January 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204073. PMID 11244506.

- ↑ "Direct interaction between BRCA1 and the estrogen receptor regulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) transcription and secretion in breast cancer cells". Oncogene 21 (50): 7730–9. October 2002. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205971. PMID 12400015.

- ↑ "BRCA1 interacts directly with the Fanconi anemia protein FANCA". Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 (21): 2591–7. October 2002. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.21.2591. PMID 12354784.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 "BRCA1-independent ubiquitination of FANCD2". Mol. Cell 12 (1): 247–54. July 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00281-8. PMID 12887909.

- ↑ "BRCA1 interacts with FHL2 and enhances FHL2 transactivation function". FEBS Lett. 553 (1–2): 183–9. October 2003. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00978-5. PMID 14550570.

- ↑ "[Isolation and characterization of a BRCA1-interacting protein]" (in zh). Yi Chuan Xue Bao 30 (12): 1161–6. December 2003. PMID 14986435.

- ↑ 177.0 177.1 "Activation of the E3 ligase function of the BRCA1/BARD1 complex by polyubiquitin chains". EMBO J. 21 (24): 6755–62. December 2002. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf691. PMID 12485996.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 "Autoubiquitination of the BRCA1*BARD1 RING ubiquitin ligase". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (24): 22085–92. June 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201252200. PMID 11927591.

- ↑ "A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage". Curr. Biol. 10 (15): 886–95. 2000. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00610-2. PMID 10959836.

- ↑ "Mutational analysis of the LMO4 gene, encoding a BRCA1-interacting protein, in breast carcinomas". Int. J. Cancer 107 (1): 155–8. October 2003. doi:10.1002/ijc.11343. PMID 12925972.

- ↑ "The LIM domain protein LMO4 interacts with the cofactor CtIP and the tumor suppressor BRCA1 and inhibits BRCA1 activity". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (10): 7849–56. March 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110603200. PMID 11751867.

- ↑ "BRCA1 interacts with and is required for paclitaxel-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 3". Cancer Res. 64 (12): 4148–54. June 2004. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4080. PMID 15205325.

- ↑ 183.0 183.1 183.2 183.3 183.4 "Redistribution of BRCA1 among four different protein complexes following replication blockage". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (42): 38549–54. October 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105227200. PMID 11504724.

- ↑ "The BRCA1 and BARD1 association with the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme". Cancer Res. 62 (15): 4222–8. August 2002. PMID 12154023.

- ↑ 185.0 185.1 "BRCA1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (11): 5605–10. May 1997. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.11.5605. PMID 9159119. Bibcode: 1997PNAS...94.5605S.

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 186.2 "Association of BRCA1 with the hRad50-hMre11-p95 complex and the DNA damage response". Science 285 (5428): 747–50. July 1999. doi:10.1126/science.285.5428.747. PMID 10426999.

- ↑ "Direct DNA binding by Brca1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (11): 6086–91. May 2001. doi:10.1073/pnas.111125998. PMID 11353843.

- ↑ 188.0 188.1 "A novel tricomplex of BRCA1, Nmi, and c-Myc inhibits c-Myc-induced human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT) promoter activity in breast cancer". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (23): 20965–73. June 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112231200. PMID 11916966.

- ↑ "BRCA1 inhibition of telomerase activity in cultured cells". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (23): 8668–90. December 2003. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.23.8668-8690.2003. PMID 14612409.

- ↑ "Inhibition of human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene expression by BRCA1 in human ovarian cancer cells". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 303 (1): 130–6. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00318-8. PMID 12646176.

- ↑ 191.0 191.1 "Nucleophosmin/B23 is a candidate substrate for the BRCA1-BARD1 ubiquitin ligase". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (30): 30919–22. July 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.C400169200. PMID 15184379.

- ↑ "Breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCAI) is a coactivator of the androgen receptor". Cancer Res. 60 (21): 5946–9. November 2000. PMID 11085509.

- ↑ "BRCA1 cooperates with NUFIP and P-TEFb to activate transcription by RNA polymerase II". Oncogene 23 (31): 5316–29. July 2004. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207684. PMID 15107825.

- ↑ "Functional and physical interactions between BRCA1 and p53 in transcriptional regulation of the IGF-IR gene". Horm. Metab. Res. 35 (11–12): 758–62. 2003. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814154. PMID 14710355.

- ↑ "BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (5): 2302–6. March 1998. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. PMID 9482880. Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.2302O.

- ↑ "BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity". Oncogene 16 (13): 1713–21. April 1998. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201932. PMID 9582019.

- ↑ "PALB2 is an integral component of the BRCA complex required for homologous recombination repair". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (17): 7155–60. April 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811159106. PMID 19369211. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.7155S.

- ↑ "BRCA1 associates with processive RNA polymerase II". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (52): 52012–20. December 2003. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308418200. PMID 14506230.

- ↑ "Bovine BRCA1 shows classic responses to genotoxic stress but low in vitro transcriptional activation activity". Oncogene 22 (38): 6032–44. September 2003. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206515. PMID 12955082.

- ↑ "Regulation of BRCA1 phosphorylation by interaction with protein phosphatase 1alpha". Cancer Res. 62 (22): 6357–61. November 2002. PMID 12438214.

- ↑ "Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells". Cell 88 (2): 265–75. January 1997. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81847-4. PMID 9008167.

- ↑ 202.0 202.1 202.2 "BRCA1 interacts with components of the histone deacetylase complex". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (9): 4983–8. April 1999. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.4983. PMID 10220405. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...96.4983Y.

- ↑ "Rb-associated protein 46 (RbAp46) inhibits transcriptional transactivation mediated by BRCA1". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284 (2): 507–14. June 2001. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5003. PMID 11394910.

- ↑ 204.0 204.1 "Identification of proteins that interact with BRCA1 by Far-Western library screening". J. Cell. Biochem. 83 (4): 521–31. 2001. doi:10.1002/jcb.1257. PMID 11746496. https://zenodo.org/record/1229223.

- ↑ "The C-terminal (BRCT) domains of BRCA1 interact in vivo with CtIP, a protein implicated in the CtBP pathway of transcriptional repression". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (39): 25388–92. September 1998. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.39.25388. PMID 9738006.

- ↑ "Binding of CtIP to the BRCT repeats of BRCA1 involved in the transcription regulation of p21 is disrupted upon DNA damage". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (16): 11334–8. April 1999. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.16.11334. PMID 10196224.

- ↑ "Characterization of a carboxy-terminal BRCA1 interacting protein". Oncogene 17 (18): 2279–85. November 1998. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202150. PMID 9811458.

- ↑ "Functional link of BRCA1 and ataxia telangiectasia gene product in DNA damage response". Nature 406 (6792): 210–5. July 2000. doi:10.1038/35018134. PMID 10910365. Bibcode: 2000Natur.406..210L.

- ↑ "Effect of DNA damage on a BRCA1 complex". Nature 414 (6859): 36. November 2001. doi:10.1038/35102118. PMID 11689934.

- ↑ "Nuclear localization and cell cycle-specific expression of CtIP, a protein that associates with the BRCA1 tumor suppressor". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (24): 18541–9. June 2000. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909494199. PMID 10764811.

- ↑ 211.0 211.1 211.2 "Disruption of BRCA1 LXCXE motif alters BRCA1 functional activity and regulation of RB family but not RB protein binding". Oncogene 20 (35): 4827–41. August 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204666. PMID 11521194.

- ↑ "BRCA1-associated growth arrest is RB-dependent". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (21): 11866–71. October 1999. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.11866. PMID 10518542. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...9611866A.

- ↑ 213.0 213.1 "BRCA1 is associated with a human SWI/SNF-related complex: linking chromatin remodeling to breast cancer". Cell 102 (2): 257–65. July 2000. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00030-1. PMID 10943845.

- ↑ "BRCA1 interacts with dominant negative SWI/SNF enzymes without affecting homologous recombination or radiation-induced gene activation of p21 or Mdm2". J. Cell. Biochem. 91 (5): 987–98. April 2004. doi:10.1002/jcb.20003. PMID 15034933.

- ↑ "Collaboration of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and BRCA1 in differential regulation of IFN-gamma target genes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (10): 5208–13. May 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.080469697. PMID 10792030. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.5208O.

- ↑ "Function of TopBP1 in Genome Stability". Genome Stability and Human Diseases. Subcellular Biochemistry. 50. Springer Dordrecht. April 2012. pp. 119–141. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3471-7_7. ISBN 978-90-481-3471-7.

- ↑ "Binding and recognition in the assembly of an active BRCA1/BARD1 ubiquitin-ligase complex". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (10): 5646–51. May 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0836054100. PMID 12732733. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.5646B.

- ↑ "Mass spectrometric and mutational analyses reveal Lys-6-linked polyubiquitin chains catalyzed by BRCA1-BARD1 ubiquitin ligase". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (6): 3916–24. February 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308540200. PMID 14638690.

- ↑ "Control of biochemical reactions through supramolecular RING domain self-assembly". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (24): 15404–9. November 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.202608799. PMID 12438698. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...9915404K.

- ↑ "The BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer assembles polyubiquitin chains through an unconventional linkage involving lysine residue K6 of ubiquitin". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (37): 34743–6. September 2003. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300249200. PMID 12890688.

- ↑ "The RING heterodimer BRCA1-BARD1 is a ubiquitin ligase inactivated by a breast cancer-derived mutation". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (18): 14537–40. May 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.C000881200. PMID 11278247.

- ↑ "Novel consensus DNA-binding sequence for BRCA1 protein complexes". Mol. Carcinog. 38 (2): 85–96. October 2003. doi:10.1002/mc.10148. PMID 14502648. https://zenodo.org/record/1229285.

- ↑ "VCP, a weak ATPase involved in multiple cellular events, interacts physically with BRCA1 in the nucleus of living cells". DNA Cell Biol. 19 (5): 253–63. May 2000. doi:10.1089/10445490050021168. PMID 10855792.

- ↑ "Association of BRCA1 with the inactive X chromosome and XIST RNA". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359 (1441): 123–8. January 2004. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1371. PMID 15065664.

- ↑ "BRCA1 supports XIST RNA concentration on the inactive X chromosome". Cell 111 (3): 393–405. November 2002. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01052-8. PMID 12419249.

- ↑ "Sequence-specific transcriptional corepressor function for BRCA1 through a novel zinc finger protein, ZBRK1". Mol. Cell 6 (4): 757–68. October 2000. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00075-7. PMID 11090615.

External links

- BRCA1 Protein at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Genes, BRCA1 at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human BRCA1.

|