- Chapter 1: Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Applications

- Chapter 2: Data Model and Query Languages

- Chapter 3: Storage and retrieval

- Chapter 4: Encoding and Evolution

- Chapter 5: Replication

- Chapter 6: Partitioning

- Chapter 7: Transactions

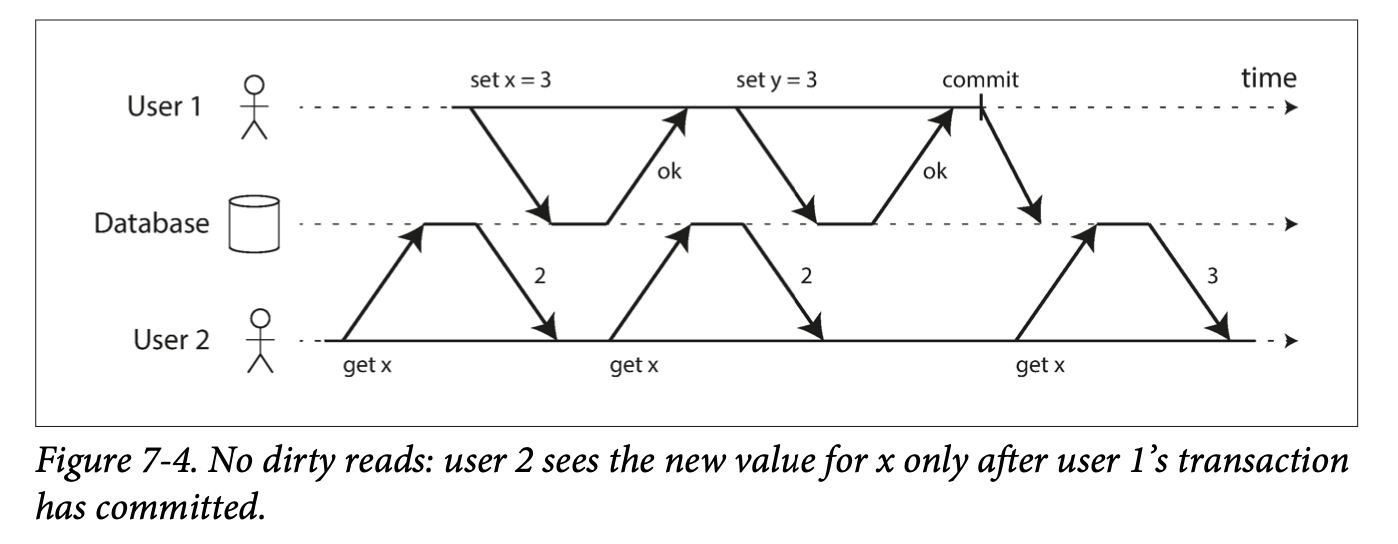

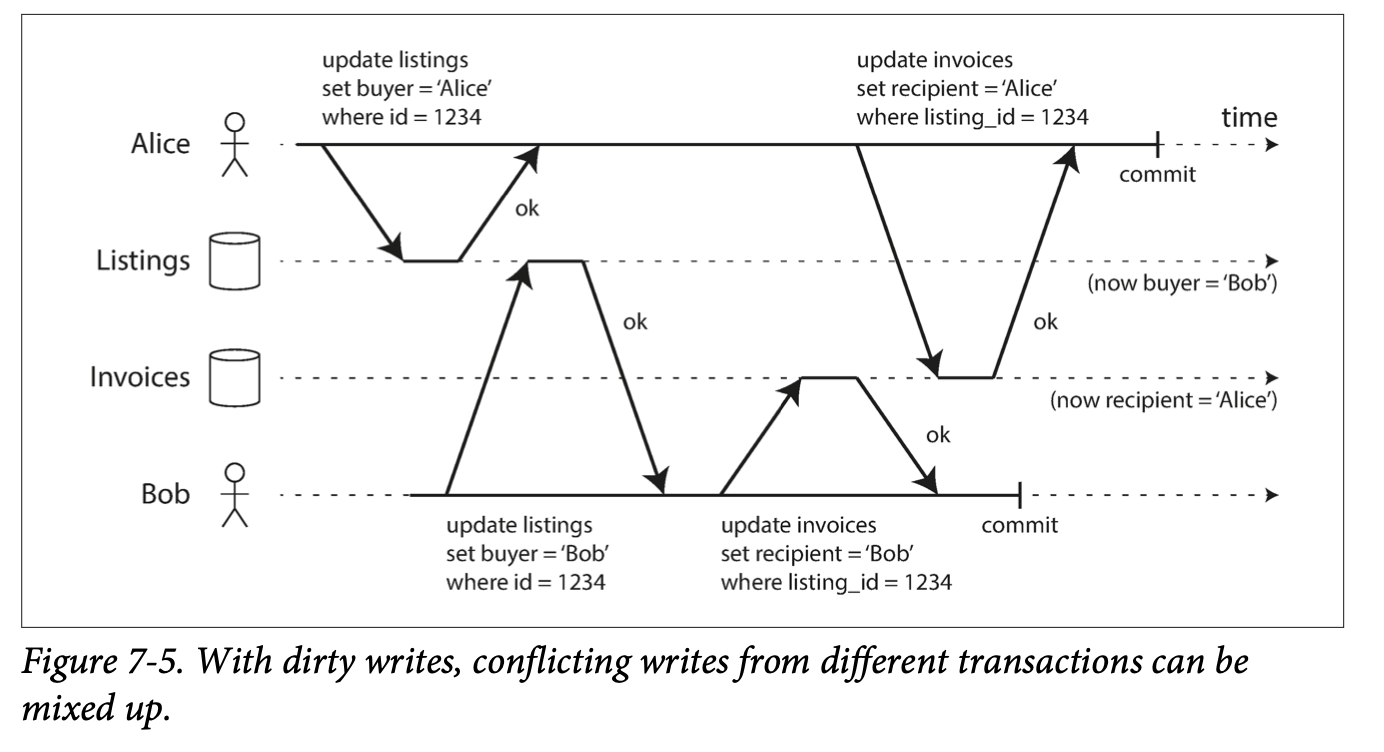

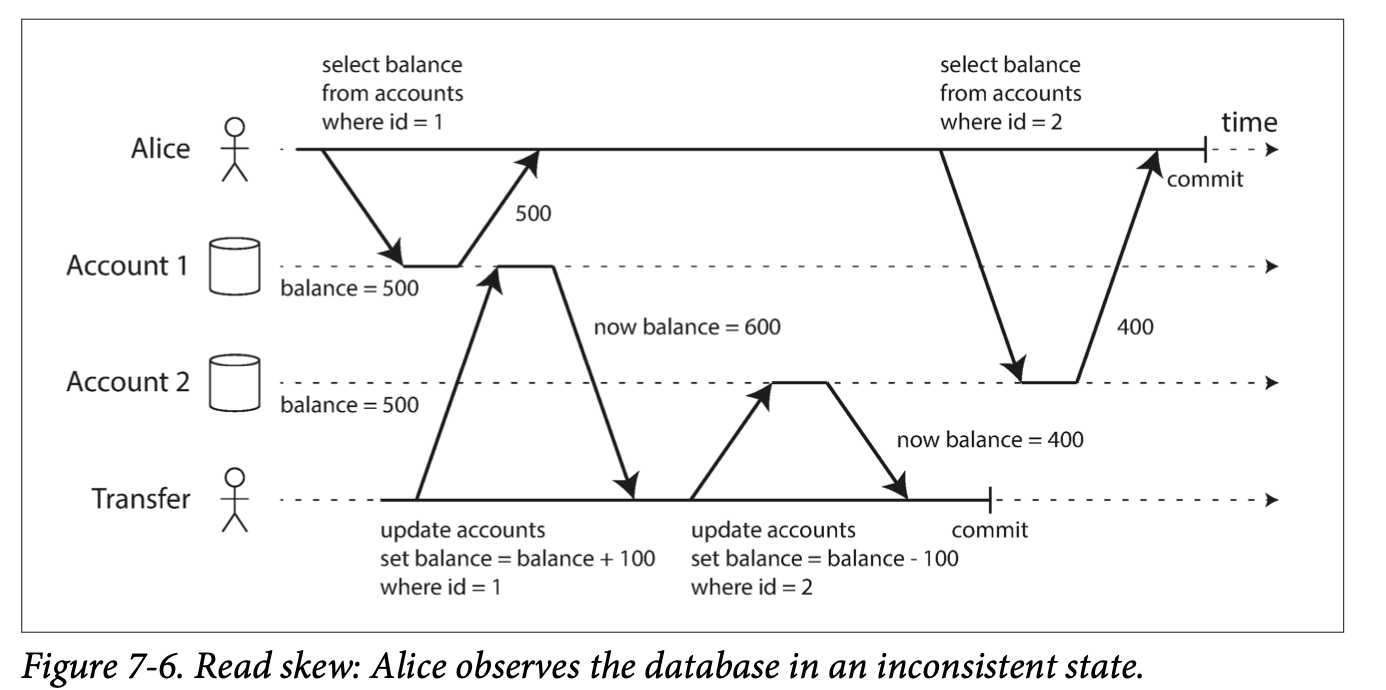

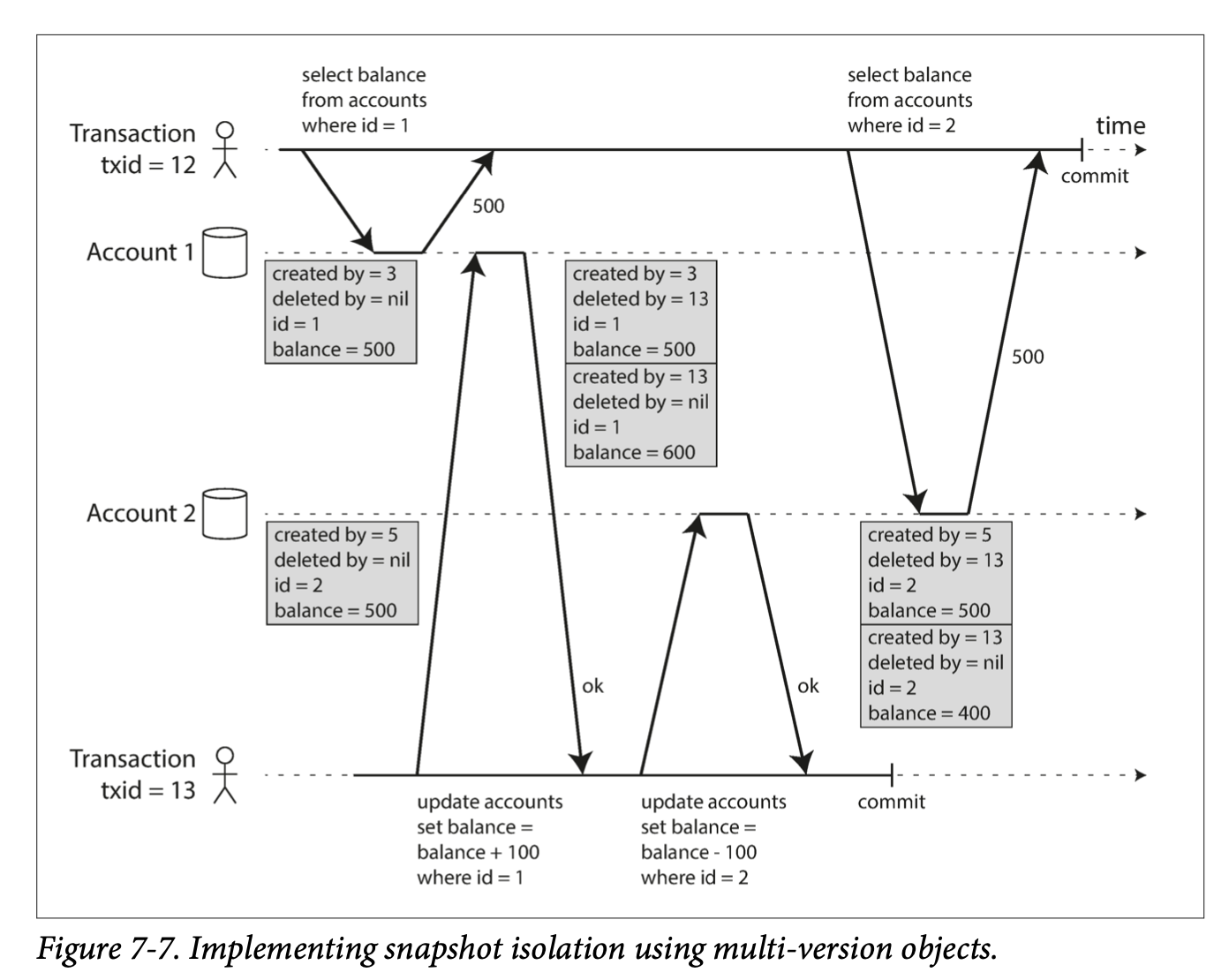

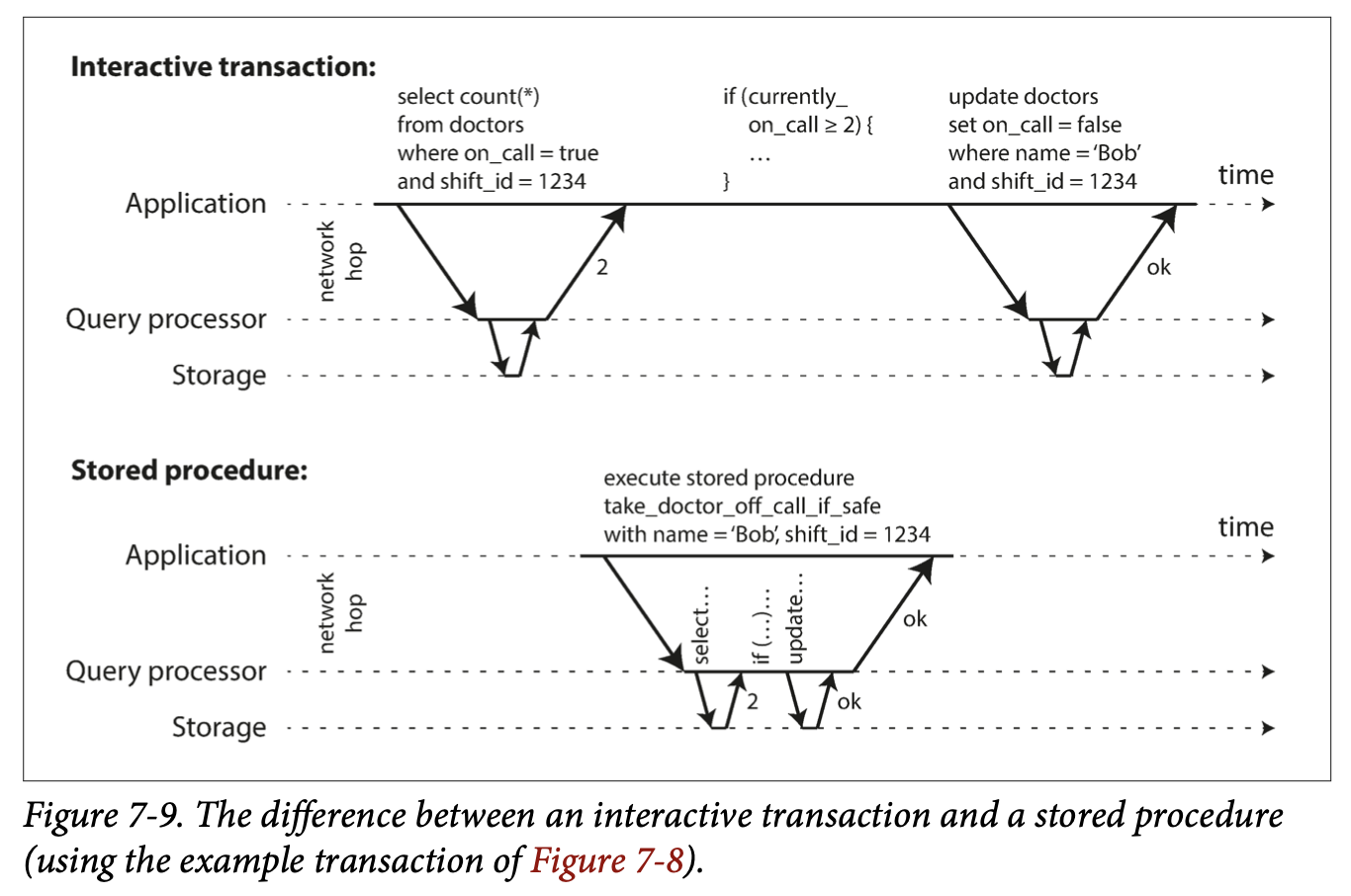

- Chapter 8: The Trouble with Distributed Systems

- Chapter 9: Consistency and Consensus

- Chapter 10: Batch Processing

- Chapter 11: Stream Processing

We call an application data-intensive if data is its primary challenge - the quantity of data, the complexity of data, or the speed at which it is changing - as opposed to compute-intensive, where CPU cycles are the bottleneck.

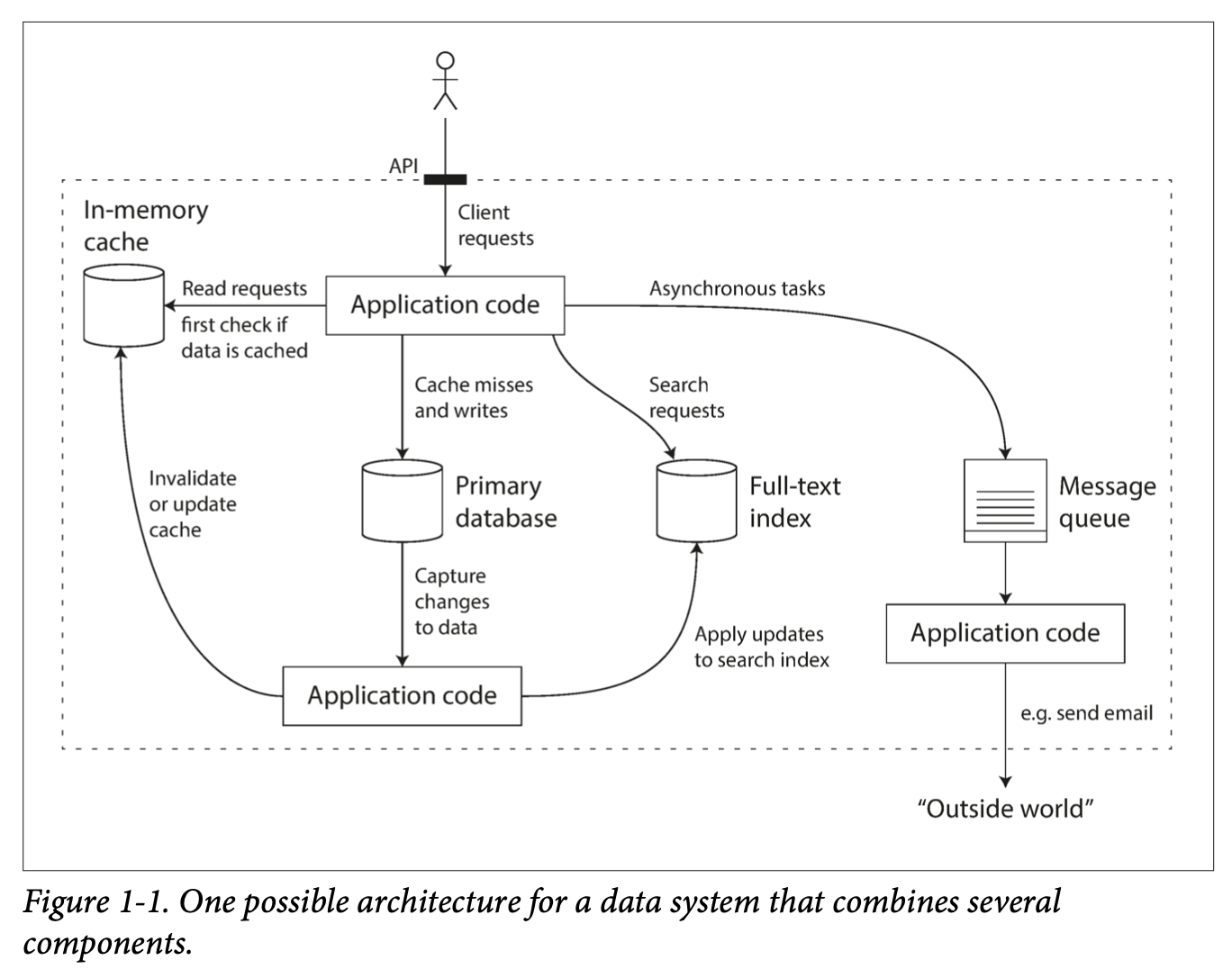

- A data-intensive application is typically built from standard building blocks that provide commonly needed functionality. Many applications need to:

- Store data so that they, or another application, can find it again later (databases)

- Remember the result of an expensive operation, to speed up reads (caches)

- Allow users to search data by keyword or filter it in various ways (search indexes)

- Send a message to another process, to be handled asynchronously (stream processing)

- Periodically crunch a large amount of accumulated data (batch processing)

Although a database and a message queue have some superficial similarity - both store data for some time - they have very different access patterns, which means different characterstics, and thus very different implementation.

There are datastores that are also used as message queues (Redis), and there are message queues with database-like durability guarantees (Apache Kafka).

If you have an application-managed caching layer (using Memcached or similar), or a full-text search server (such as Elasticsearch or Solr) separate from your main database, it is normally the application code’s responsibility to keep those caches and indexes in sync with the main database.

Stitching smaller systems together results in a larger data system, with different characteristics.

Figure 1-1 One possible architecture for a data system that combines several components.

We focus on three concerns that are important in most software systems:

- Reliability: The system should work correctly (performing the correct function at the desired level of performance) even in the face of adversity.

- Scalability: As the system grows(in data , traffic volume, or complexity), there should be reasonable ways of dealing with that growth.

- Maintainability: People should be able to work on the system productively in the future.

- Continue to work when faults (NOT failure!) occur. We say such a system is fault-tolerant.

- Faults is defined as components of the system deviating from the spec while failure is defined as a system stop working entirely.

- It is impossible to reduce faults to 0; therefore, we should design a system that tolerates faults.

- Introducing random faults (as in Netflix Chaos Monkey) could improve confidence in fault tolerant systems.

- For security issues, we would prefer to prevent faults over tolerating them, as security breaches cannot be cured.

- In the past, people use redundant hardware to keep machine/service running.

- Hard disks are reported as having a mean time to failure (MTTF) of about 10 to 50 years. Thus, on a storage cluster with 10,000 disks, we should expect on average one disk to die per day.

- AWS’s virtual machine platforms are designed to prioritize flexibility and elasticity over single-machine reliability.

- Recently, platforms are designed to prioritize flexibility and elasticity. Systems can tolerate loss of whole machines. No down time scheduled needed for single machine maintenance.

- Software errors/bugs are more systematic. They impact all machines in the same service.

- Alerts can help check the SLA guarantees.

- Most outages are human errors. We can

- Minimize opportunities for errors through designs.

- Decouple where mistakes are made (sandbox) and where the mistakes causes failures (production).

- Test thoroughly, including unit, integration, and manual tests.

- Allow quick and easy recovery to minimize impact.

- Set up clear monitoring on performance metrics and error rates.

- Reliability is important for the business. Any down time could be revenue losses.

- There are situations where we may tradeoff reliability for lower development cost, but we should be very conscious when we are cutting corners.

- Scalability is the term we use to describe a system’s ability to cope with increased load.

-

Described with load parameters, which has different meaning under different architectures. It can be requests per second for services, read write ratio for databases, number of simultaneous users. Sometimes the average case matters, and sometimes the bottleneck is dominated by a few extreme cases.

-

Twitter example

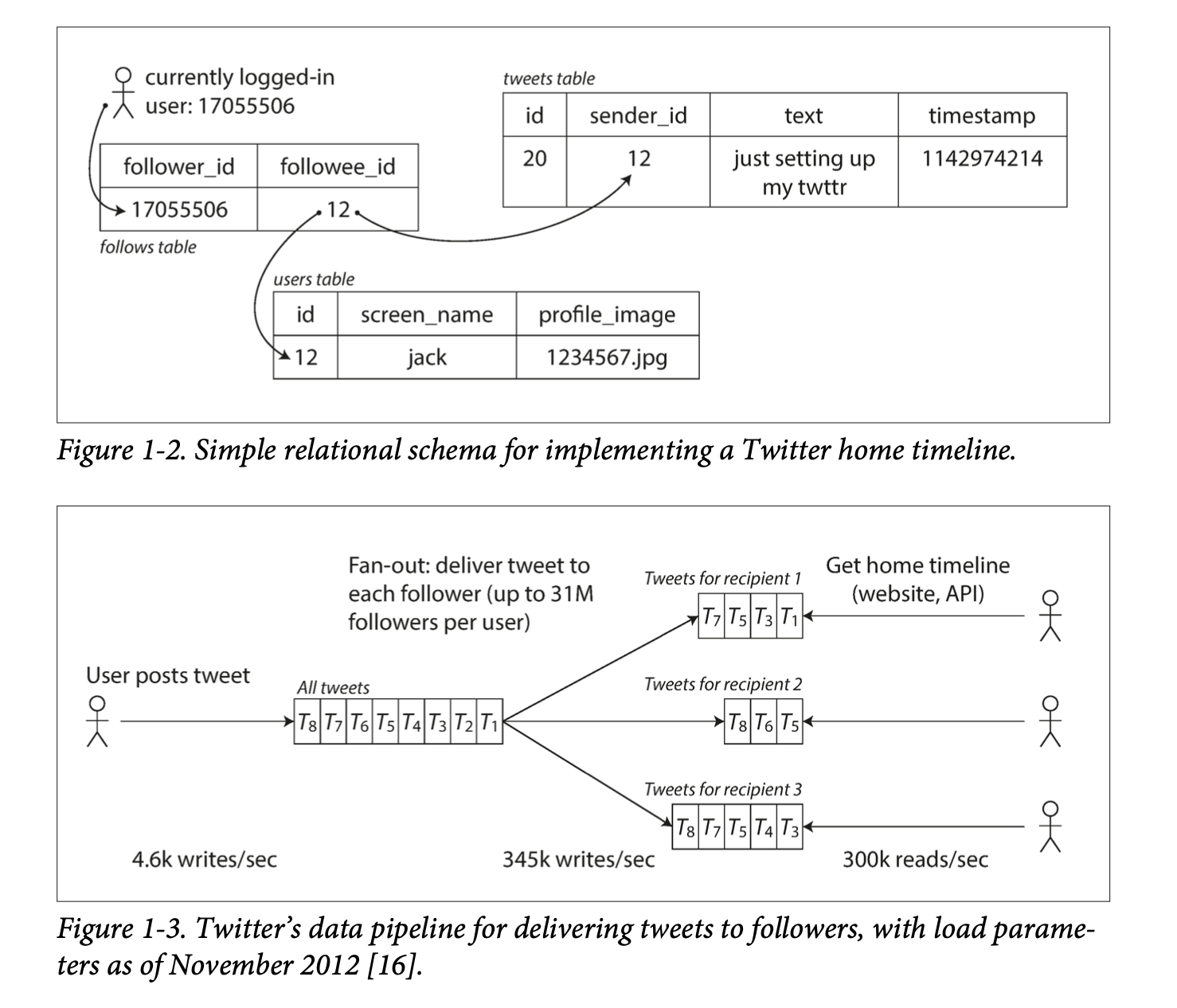

- Twitter has two main operations: post Tweet and home timeline (~100x more requests than post Tweet).

- Approach 1: If we store Tweets in a simple database, home timeline queries may be slow. Posting a tweet simply inserts the new tweet into a global collection of tweets. When a user requests their home timeline, look up all the people they follow, find all the tweets for each of those users, and merge them.

- Approach 2: We can push Tweets into the home timeline cache of each follower when a Tweet is published. Maintain a cache for each user’s home timeline — like a mailbox of tweets for each recipient user. When a user posts a tweet, look up all the people who follow that user, and insert the new tweet into each of their home timeline caches.

- Approach 2 does not work for users with many followers, since the approach would need to update too many home timeline caches.

- Distribution of followers in this case is a load parameter.

- We can use approach 1 for users with many followers and approach 2 for the others.

- Twitter is now implementing a hybrid of both approaches. For most users, tweets continue to be fanned out to home timelines at the time when they are posted. However, for a small number of users with millions of followers (celebrities), they are exempted from the fan out.

- Two ways to look at performance.

- When we increase load parameters and keep resources unchanged. How is the performance affected.

- When we increase load parameters how much resource do we need to keep performance unchanged.

- Batch processing systems cares about throughput (number of records processed per second).

- Online systems cares about the response time, which is measured in percentiles like p50, p90, p99, p999.

- Random additional latency could be introduced by a context switch to a background process, the loss of a network packet and TCP retransmission, a garbage collection pause, a page fault forcing a read from disk, mechanical vibrations in the server rack, or many other causes.

- Tail latencies (p999) are sometimes important as they are usually requests from users with a lot of data.

- Percentiles are often used in service level objectives (SLOs) and service level agreements (SLAs)

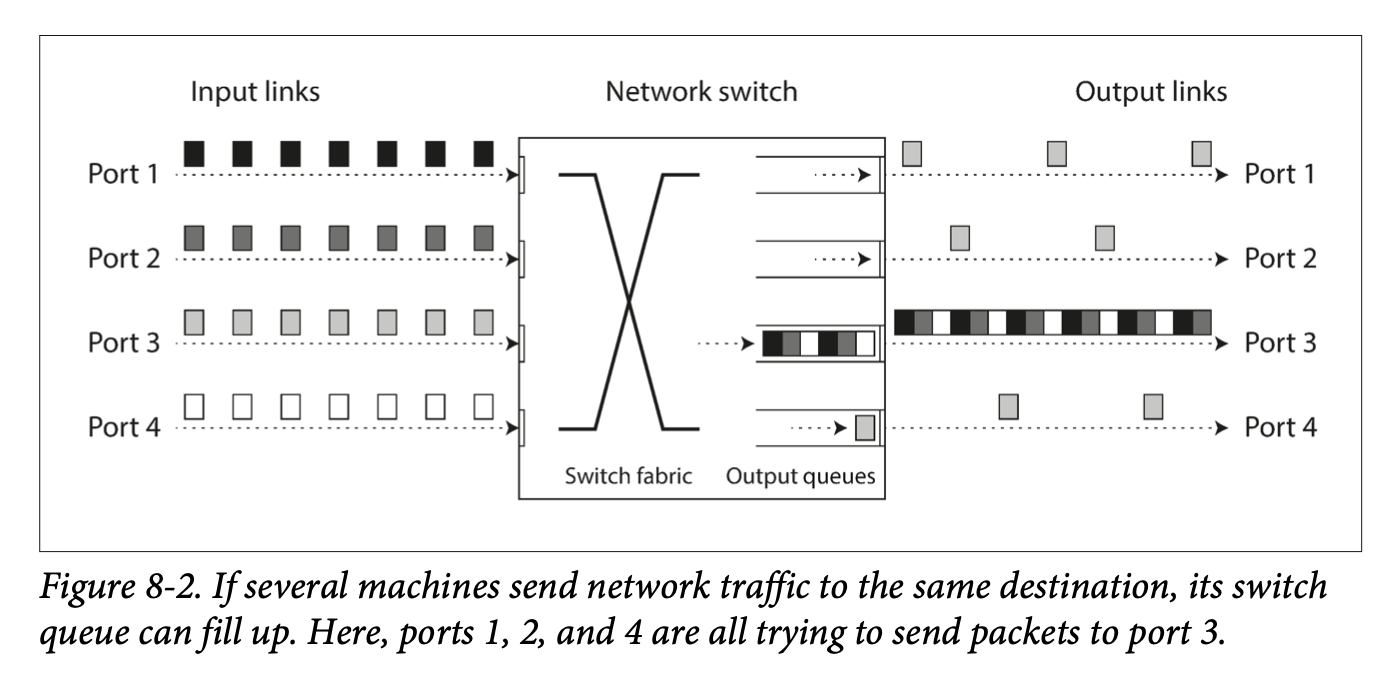

- Queuing delays often account for a large part of high percentiles. Since parallelism is limited in servers. Slow requests may cause head-of-line blocking and make subsequent requests slow.

- The latency from an end user request is the slowest of all the parallel calls. The more backend calls we make, the higher the chance that one of the requests were slow. This is known as tail latency amplification.

- Scaling up (vertical scaling, with a more powerful machine) and scaling out (horizontal scaling, distributing the load across multiple machines, the shared-nothing architecture) are two popular approaches to cope with increasing load. Good architectures usually involves a mixture of both.

- Elastic systems can add computing resources when load increases automatically but it may have more surprises.

- Scaling up stateful data systems can be complex. For this reason, common wisdom is to use a single node until cost or availability requirements are no longer satisfied. Of course this may change in the future.

- The architecture for large scale systems is usually highly specific and built around its assumptions on which operations will be common or rare. There is no one-size-fits-all scalable architecture.

- Three design principles to minimize pain for maintenance.

- Operations are for keeping a software system running smoothly.

- Good operability means making routine tasks easy. Data systems can

- Provide visibility into the runtime behavior

- Provide support for automation and integration with standard tools

- Avoid dependencies on individual machines

- Provide good documentation

- Provide good default behavior

- Self-healing where appropriate

- Minimize surprises

- Complexity slows down engineers working on the system and increases the cost of maintenance.

- Possible complexity symptoms: explosion of state space, tight coupling of modules, tangled dependencies, inconsistent naming and terminology, hacks for solving performance problems, special cases for workarounds, etc.

- We can remove accidental complexity, which is complexity not inherent in the business problem. This can be done through abstraction and hiding implementation details.

-

System requirements will change so we need to make making changes easy.

-

Test-driven development and refactoring are tools for building software that is easier to change.

-

Refactoring large data systems is different from refactoring a small local application (Agile); therefore, we use the term evolvability to refer to ease to make changes in a data system.

-

Functional requirements: what the application should do

-

Nonfunctional requirements: general properties like security, reliability, compliance, scalability, compatibility and maintainability.

- Data models are important part of developing software, it deeply affects how we think about the problem.

- Data models are built by layering one on top of another. The key question is: “how is it represented in terms of the next-lower layer?” Each layer hides the complexity of the layers below by providing a clean model.

- The data model has a profound effect on what the software above can or cannot do.

- In this chapter, we will compare the relational model, the document model, and a few graph-based models. We will also look at and compare various query languages.

- The goal of the relational model is to hide implementation details behind a clean interface.

- SQL was rooted in relational databases for business data processing in the 1960s and 1970s, and was used for transaction processing and batch processing.

- SQL was proposed in 1970 and is probably the best-known data model, where data is organized into relations (tables), which is an unordered collection of tuples (rows).

- NoSQL was just a catchy hashtag on Twitter for a meetup. NoSQL is the latest attempt to overthrow the relational model’s dominance.

- Driving forces for NoSQL

- A need for better scalability (larger datasets, high write throughput)

- Preference for free and open source software

- Specialized query operations that are not supported by the relational model

- The restrictiveness of the relational schemas

- It’s likely that relational databases will continue to be used along with many nonrelational databases.

- With a SQL model, if data is stored in a relational tables, an awkward translation layer is translated, this is called impedance mismatch.

- Strategies to deal with the mismatch

- Normalized databases with foreign keys.

- Use a database that Supports for structured data (PostgreSQL)

- Encode as JSON or XML and store as text in database. It can’t be queried this way.

- Store as JSON in a document in document-oriented databases (MongoDB). This has a better locality than the normalized representation.

- JSON representation has better locality than the multi-table SQL schema. All the relevant information is in one place, and one query is sufficient.

- For enum-type strings, we can store a separate normalized ID to string table, and use the ID in other parts of the database. This will enforce consistency (same spelling, better search), avoid ambiguity, be easier to update, support localization.

- Using ids reduces duplication. This is the key idea behind normalizing databases. Yet this requires a many-to-one relationship, which may not work well with document databases, whose support for joins are weak.

- We then compare the data model of relational and document databases.

- Document databases: better schema flexibility, better performance due to locality, and closer to data structures in applications.

- Relational databases: better support for joins, and many-to-one and many-to-many relationships.

- Document model may be a good choice if the application has a document-like structure:tree of one-to-many relationships, while relational models may require splitting a document-like structure into multiple tables.

- Records in document models are more difficult to directly access when they are deeply nested.

- For applications with many-to-many relationships, document models are less appealing due to the poor support for joins.

- For highly interconnected data, document model is awkward, and the relational model is acceptable, and graph models are the most natural.

- XML support in relational databases usually comes with schema validation while JSON support does not.

- Document databases are sometimes called schemaless, yet there is an implicit schema. A more accurate term is schema-on-read, meaning schema is only interpreted when data is read, in contrast with schema-on-write for relational database, where validation occurs during write time.

- An analogy to type checking is dynamic type checking (runtime) and static typing checking (compile-time). In general there is no right or wrong answer.

- To change a schema in document databases, applications would start writing new documents with the new schema, while in relational databases, one would need a migration query (which is quick for most databases, except MySQL).

- Schema-on-read is advantageous if items in the collection don’t all have the same structure.

- Schema-on-write is advantageous when all records are expected to have the same structure.

- If the whole document (string of JSON, XML) is required by application often, there is a performance advantage to this storage locality (single lookup, no joins required). If only a small portion of the data is required, this can be wasteful.

- It’s generally recommended to keep documents small and avoid writes that increases the size of documents (same size updates can be done in-place).

- Google’s Spanner database allows table rows to be nested in a parent table. Oracle’s database allows multi-table index cluster tables. The column-family concept (used in Cassandra and HBase) has a similar purpose for managing locality.

- Most relational databases (except MySQL) supports XML. PostgreSQL, MySQL, DB2 supports JSON.

- RethinkDQ supports joins, and some MongoDB drivers resolves database references.

- A hybrid of relational and document models is probably the future.

- SQL is a declarative query language.

- In a declarative language, only the goal is specified, not how the goal is achieved. It hides implementation details and leaves room for performance optimization.

- The fact that SQL is more limited in functionality gives databases more room for automatic optimizations.

- Declarative code is easier to parallelize as execution order is not specified.

- CSS and XML are declarative languages to specify styling in HTML, while changing styles directly through Javascript is imperative.

- Specifying styles using CSS is much better than changing styles directly using Javascript.

- MapReduce is a programming model for processing large amounts of data in bulk across many machines, and a limited form of MapReduce is supported by MongoDB and CouchDB.

- MapReduce is somewhere between declarative and imperative.

- SQL can, but not necessarily have to, be implemented by MapReduce operations.

- MongoDB supports a declarative query language called aggregation pipeline, where users don’t need to coordinate a map and reduce function themselves.

- An application with mostly one-to-many relationships or no relationships between records, the document model is appropriate, but for many-to-many relationships, graph models are more appropriate.

- Graphs can be homogeneous, where all vertices represent the same type of object and heterogeneous, where vertices may represent completely different objects.

- In the property graph model, each vertex consists of

- A unique identifier

- A set of outgoing edges

- A set of incoming edges

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

- Each edge consists of

- A unique identifier

- The vertex at which the edge starts (the tail vertex)

- The vertex at which the edge ends (the head vertex)

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

- The property graph model is analogous to storing two relational databases, one for vertices, one for edges.

- Multiple relationships can be stored within the same graph by proper labeling the edges.

- Graphs can be easily extended to accommodate new data types.

- Cypher is a declarative query language for property graphs, created for the Neo4j graph database.

- Usually, we know which joins to run in relational database queries, yet in a graph query, the number of joins is not fixed in advance, as we may need to follow an edge multiple times.

- In a triple-store, all information is stored in a three-part statement: subject, predicate, object.

- The subject is equivalent to a vertex in a graph.

- The object can be:

- A value in a primitive datatype. In this case, the predicate and object forms the key and value of a property of the subject vertex.

- Another vertex in the graph. In this case, the predicate is the edge between the subject vertex and the object vertex.

- Databases fundamentally does two things: Store data and retrieve the stored data.

- Chapter 3 discusses how data model and queries are interpreted by databases.

- Understanding under-the-hood details can help us pick the right solution and tune the performance.

- We’ll first look at two types of storage engines: log-structured and page-oriented storage engines.

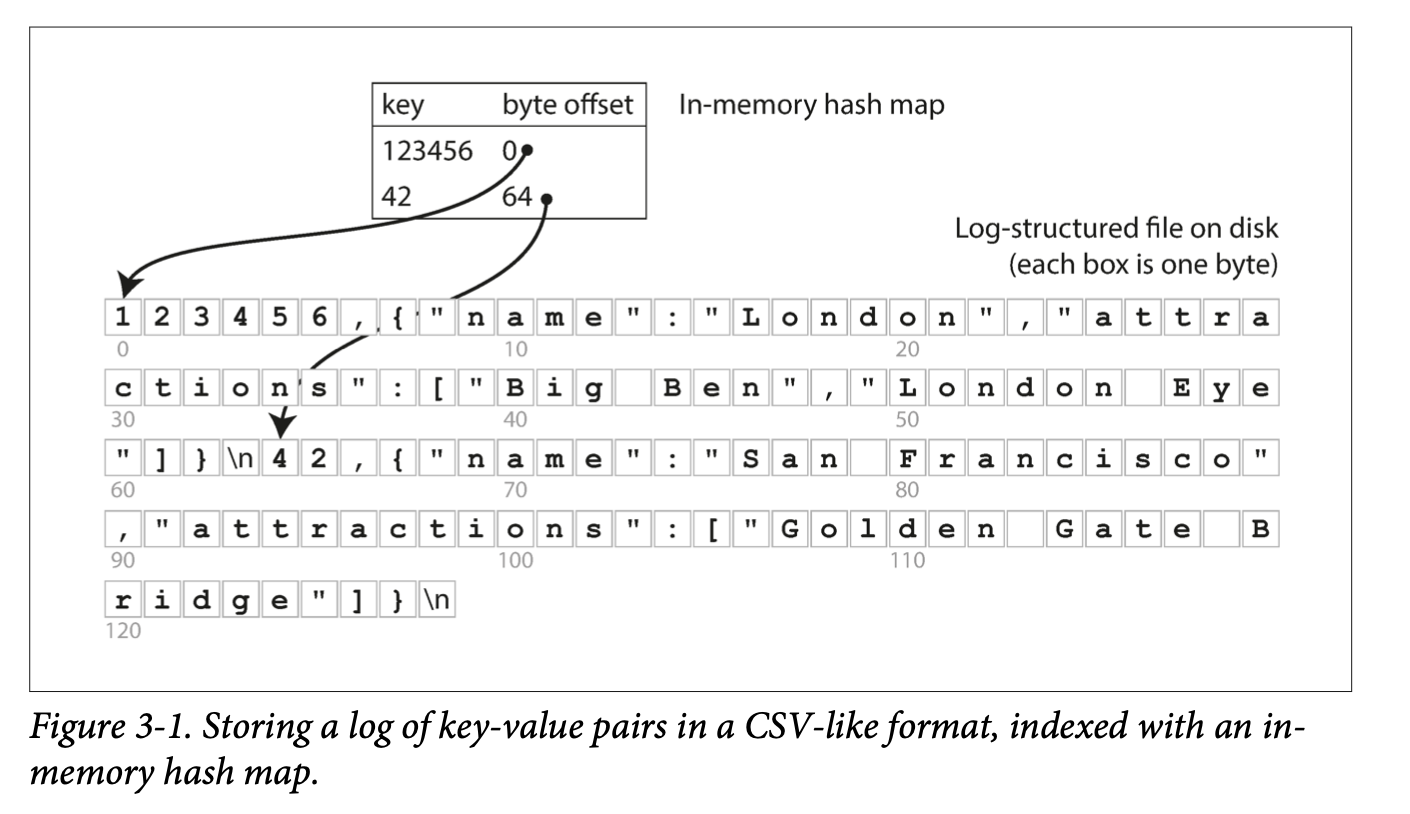

- Many databases internally uses a log, which is a append-only data file.

- To retrieve data efficiently, we need an index, which is an additional structure derived from primary data and only affects performance of queries.

- Well-chosen indexes speed up queries but slow down writes. Therefore, databases don’t index everything by default and requires developers to use knowledge of query pattens to choose index manually.

- Hash Indexes are for key-value data and are similar to a dictionary, which is usually implemented as a hash map (hash table).

- If the database writes only append new entires to a file, the hash table can simply store key to byte offset in the data file. The hash table (with keys) has to fit into memory for quick look up performance, but the values don’t have to fit into memory.

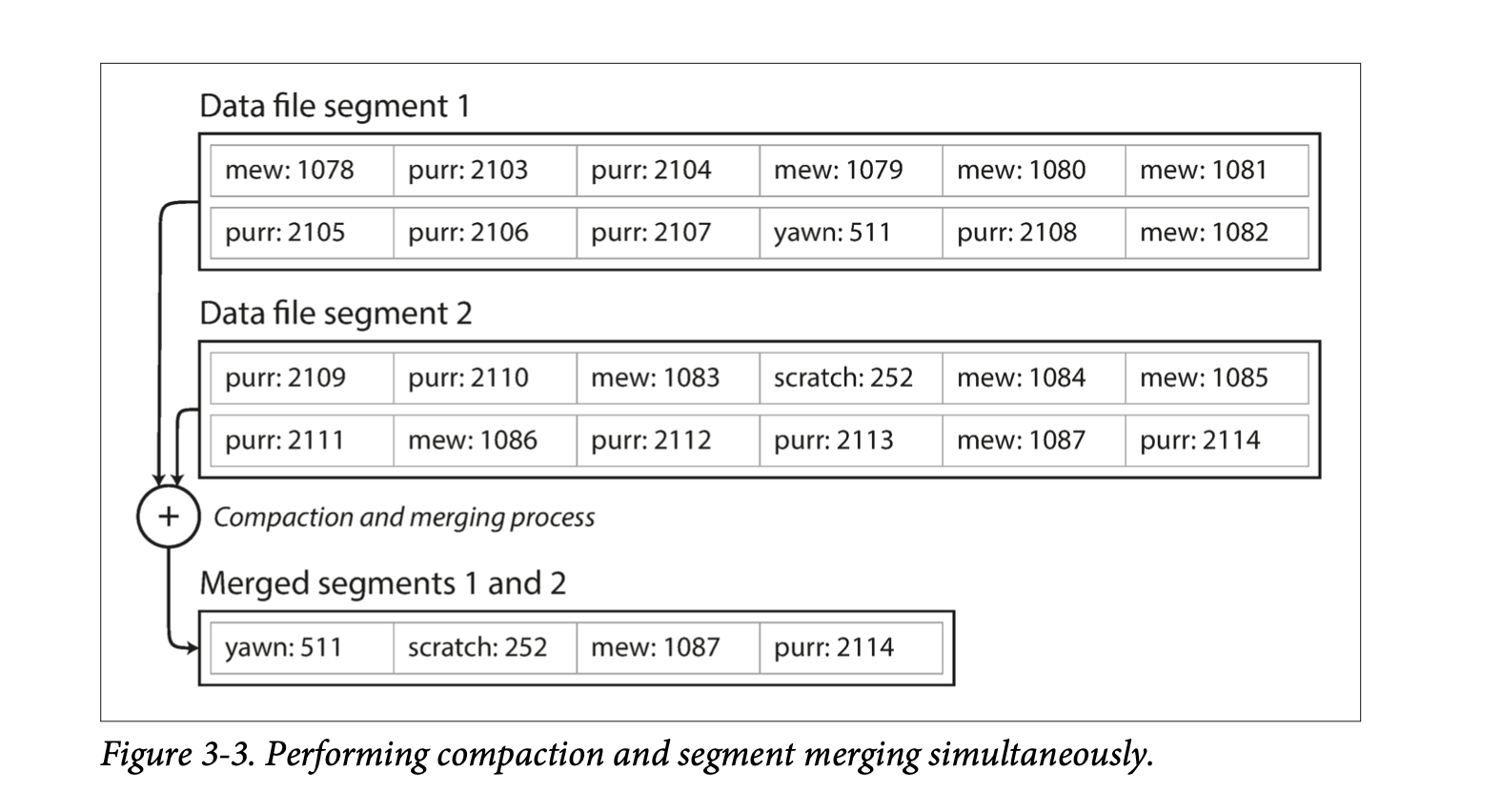

- To avoid the disk run out of space, a good solution is to break logs into segments and perform compaction (remove duplicate keys). Further, file segments can be merged while performing compaction. We can use a background thread to perform merging and compaction and switch our read request to the newly created segment when they are read. Afterwards, old segments can be deleted.

- Bitcask (the default storage engine in Riak) does it like that. The only requirement it has is that all the keys fit in the available RAM. Values can use more space than there is available in memory, since they can be loaded from disk.

- A storage engine like Bitcask is well suited to situations where the value for each key is updated frequently. There are a lot of writes, but there are too many distinct keys, you have a large number of writes per key, but it's feasible to keep all keys in memory.

- There are a few details for a real implementation of the idea above

- Use bytes instead of CSV

- Deletes are adding a special log entry to the data file (tombstone) and the data will be removed during merging and compaction.

- Index will need to be snapshotted for fast crash recovery (compared to re-indexing).

- Checksums are required for detecting partially written records.

- Writes has to strictly be in sequential order. Many implementation choose to have one writer thread.

- Why append-only logs are good

- Sequential writes are much faster than random writes, especially on magnetic spinning-disk hard drives and to some extent SSDs.

- Concurrency and crash recovery are much simpler if segment files are append-only or immutable.

- Merging old segments avoids data fragmentation.

- What are the limitations of hash table indexes?

- Hash table must fit into memory. If there are too many keys, it will not fit.

- Range queries are not efficient.

- The Sorted String Table (SSTable) requires each segment file to be sorted by key. It has the following advantages.

- Merging segments is simple and efficient.

- We no longer require offset of every single key for efficient lookup. One key for every few kilobytes of segment file is usually sufficient.

- Since reading requires a linear scan in between indexed keys, we can group those records and compress them to save storage or I/O bandwidth.

- While maintaining a sorted structure on disk is possible (B-Trees), red-black trees or AVL trees can be used to keep logs sorted in memory. The flow is as follows:

- When a write comes in, insert the entry to the in-memory data structure (sometimes called memtable).

- When memtable gets bigger than some threshold (a few megabytes), create a new memtable to handle new writes, and write the old memtable to disk.

- For reads, first try to find the key in memtable, and in the latest segment, and in the second last segment.

- Occasionally, run a merging and compaction process to combine segment files.

- The issue with this scheme is that in-memory data will be lost if the database crashes. We can keep a separate unsorted log for recovery and this log can be discarded whenever a memtable is dumped to disk.

- This indexing structure is named Log-Structure Merge-Tree (LSM-Tree).

- The algorithm here is used by LevelDB and RocksDB, which are key-value storage libraries to be used in other applications. Similar storage systems are also used in Cassandra and HBase.

- Systems that uses the principle of merging and compacting sorted files are often called LSM systems.

- A look up can take a long time if the entry does not exist in any of the memtable. Bloom filters can be used to solve this issue.

- There are two major strategies to determine the order and timing of merging and compaction: size-tiered (HBase, Cassandra) and level compaction (LevelDB, RockDB, Cassandra).

- Size-tiered: newer and smaller SSTables are merged into larger ones.

- Level: The key range is split up into several SSTables and older data is moved to separate “levels,” which allows compaction to proceed more incrementally and use less disk space.

- LSM-tree: Write throughput is high. Can efficiently index data much larger than memory.

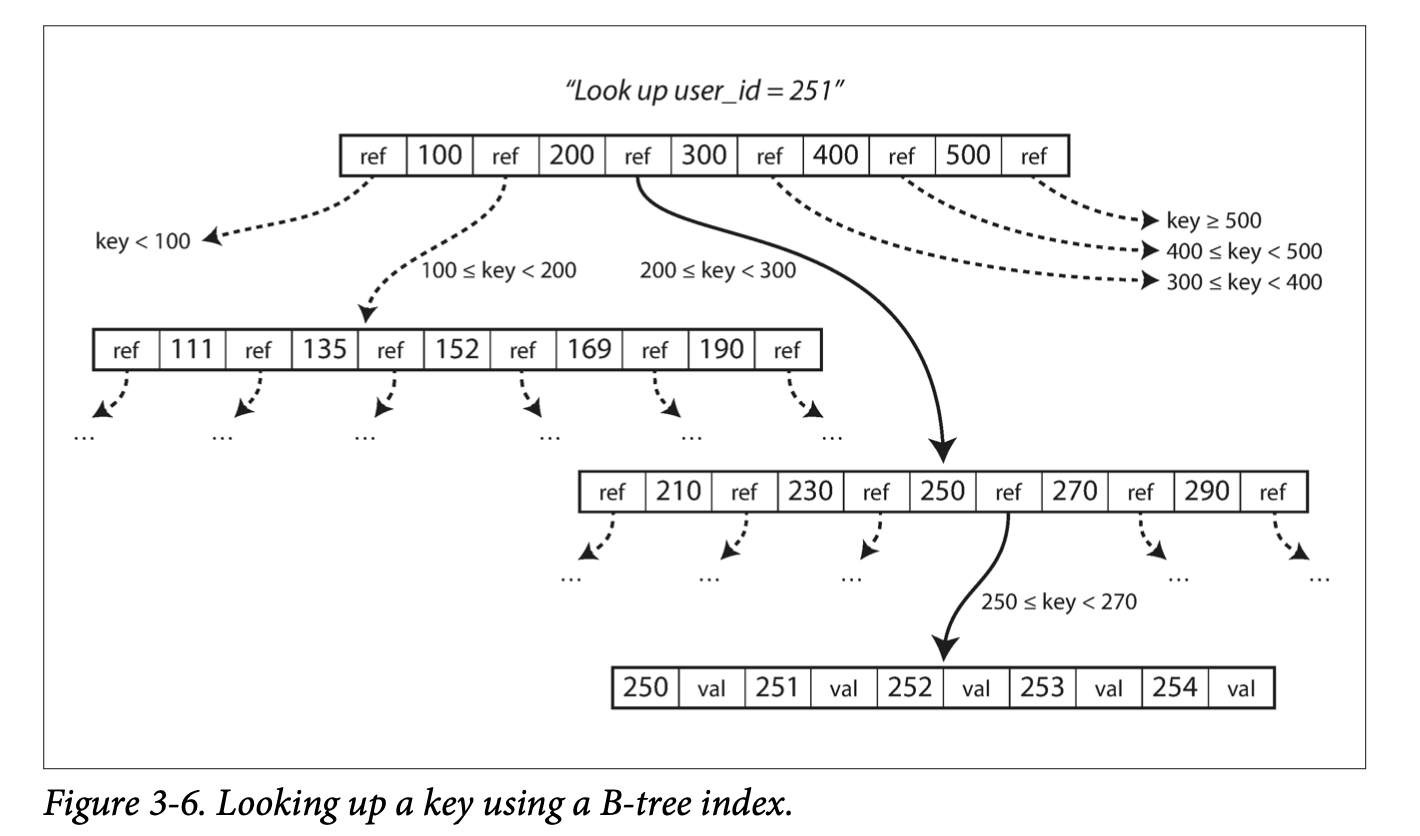

- While log-structured indexes are gaining acceptance, B-tree is the most widely used indexing structure.

- B-trees is the standard index implementation for almost all relational databases and most non-relational databases.

- B-trees also keep key-value entires sorted by key, which allows quick value lookups and range queries.

- Log-structure indexes breaks databases down into variable length segments (several mbs or more), while B-tree breaks databases down into a fixed-size blocks or pages (4KB traditionally, but depends on underlying hardware).

- Each page can be identified by an address or location, which can be stored in another page on disk.

- A root page contains the full range of keys (or reference to pages containing the full range) and is where query start.

- A leaf page contains only individual keys, which contains the value inline or reference to where the values can be found.

- The branching factor is the number of references to a child page in one page of a B-tree.

- When changing values in B-trees, the page containing the value is looked up, modified, and written back to disk.

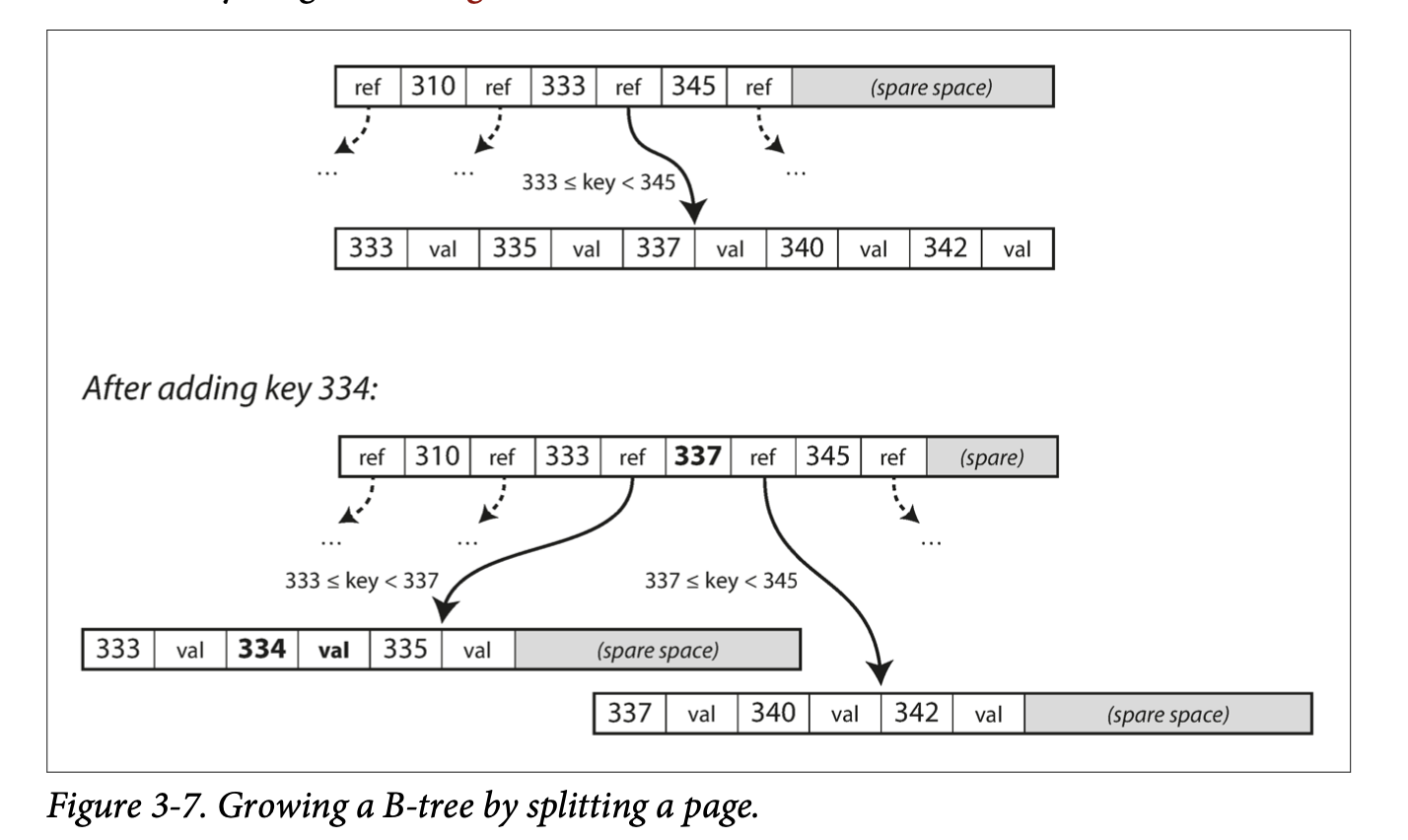

- When adding new values, first, the page whose range contains the key is looked up. If there is extra space in the page, the key-value entry is simply added, else, the page is split into two halves and the parent page is updated to account for the new file structure.

- The algorithm above ensures a B-tree with n nodes is always balanced and has a depth of O(logn).

- When changing values or splitting pages, the B-tree overwrites data on disk. This is a risky operation. If anything crashes during an overwrite, the index could be corrupted.

- To make B-tree more resilient to such failures, a common solution is to include an write-ahead-log (WAL, or redo log), which every B-tree modification is first written to. In case of failure, this log can be used to restore the B-tree back to a consistent state.

- Care should also be taken when multiple threads may access the B-tree at the same time. An inconsistent state could be read during an update. Latches (lightweight locks) can be placed to protect the tree’s integrity.

- Just to mention a few optimizations:

- Copy-on-write and atomic to remove the need to maintain a WAL for crashes

- Key compression by storing essential information for acting as boundaries.

- Arrange page on disk such that pages appear in sequential order on disk.

- Additional pointers (such as left, right siblings) to allow efficient scanning of keys in order without jumping back to parents.

- Fractal trees to reduce disk seeks.

- Typically, B-Trees are faster for reads and LSM-Trees are faster for writes. The actual performance for a specific system would require benchmarking.

- Both B-Tree and LSM-tree indexes would require writing a piece of data to disk multiple times on write. This effect is known as write amplification. In write heavy applications, write amplification would directly impact performance.

- LSM-trees are typically able to sustain higher write throughput due to two main reasons: a lower write amplification and a sequential write (especially on magnetic hard drives).

- LSM-trees can be compressed better and have lower fragmentation due to rewriting of SSTables.

- Even on SSDs, LSM-trees are still advantages as it represents data more compactly and allows more read and write requests within the same bandwidth.

- The compaction process of LSM-trees can sometimes interfere with reads and writes, as reads and writes can be blocked by the compaction process on disk resources. Although the impact on average response time is usually small, this could greatly increase high-percentage response time.

- If write throughput is high and compaction is not configured correctly, it is not impossible that compaction can’t keep up with incoming writes. Unmerged segments will then grow until disk space is all used. This effect has to be actively monitored.

- Since each key only appears once in a B-tree, B-trees are more attractive in databases when transaction isolation is implemented using locks on range of keys.

- Secondary indexes can be created from a key-value index. The main difference between primary and secondary indexes is that secondary indexes are not unique. This can be solved two ways:

- Make the value in the index a list of matching row identifiers.

- Make each key unique by adding a row identifier to the secondary key.

- Both B-trees and log-structured indexes can be used as secondary indexes.

- In a key-value pair, the key is used to locate the entry and the value can be either the actual data or a reference to the storage location (known as a heap file). Using heap files is common for building multiple secondary indexes to reduce duplication.

- When updating values without changing keys, if the new value is no larger than old data, the value can be directly overwritten, and if the new value is larger, either all indexes needs to be updated or a forwarding pointer can be left in the old record.

- Sometimes, the extra hop to the heap file is too expensive for reads, and the indexed row is stored directly in the index. This is called a clustered index.

- A compromise between a non-clustered index and a clustered index is a covering index or index with included columns, where only some columns are stored within the index.

- Multi-column indexes are created for querying rows using multiple columns of a table.

- The concatenate index is the most common multi-column index. This is done by simply concatenating fields together into one key. However the index is useless when a query is based on only one column.

- To index a two-dimensional location database (with latitude and longitude), we can use a space-filling curve and use a regular B-tree index. Specialized spatial index such as R-trees are also used.

- Some applications require searching for a similar key. This can be done by fuzzy indexes.

- For example, Lucene allows searching for words within edit distance 1. In Lucene, the in-memory index is a finite state automaton over the characters in the keys (similar to a trie). This automaton can then be transformed into a Levenshtein automaton, which supports efficient search for words within a given distance.

- Some in-memory key-value stores, such as Memcached, are intended for caching only, where data is lost when the machine restarts. Some other in-memory databases aim for durability, which can be achieved with special hardware and saving change logs and snapshots to disk.

- Counterintuitively, in-memory databases are faster mainly because they avoid serialization and deserialization between in-memory structures and binaries, not because of the disk read and write time.

- In-memory databases could also provide data models that are hard to implement with disk-based indexes, such as priority queues, stacks.

- The anti-caching approach, where the least-recently-used data is dumped to disk when there is not enough memory and loaded back when queried, enables in-memory databases to support larger-than-memory databases. Yet the index would still have to fit into memory.

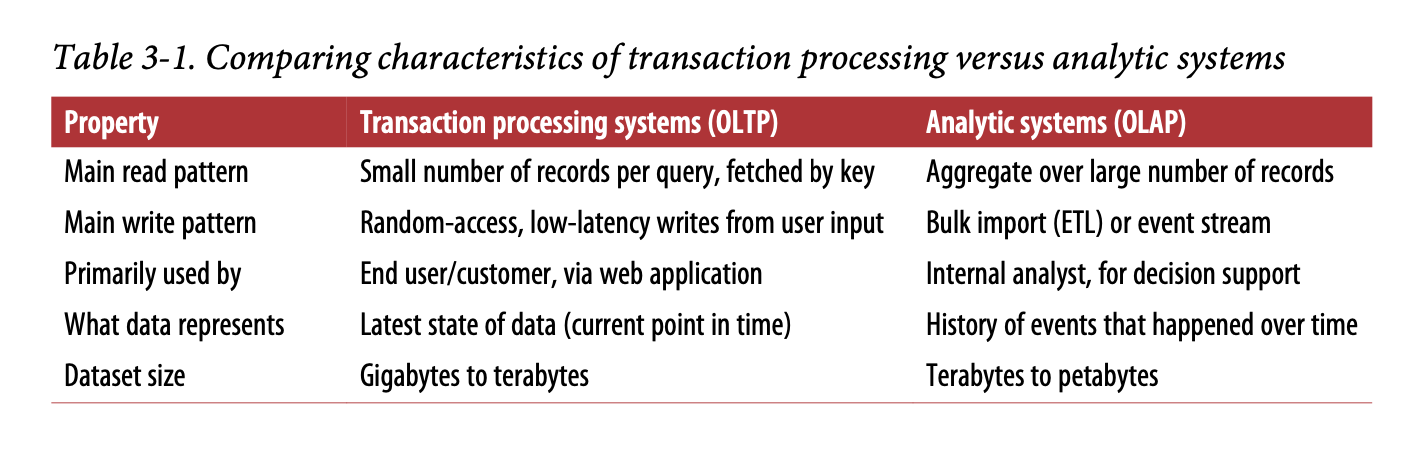

- The term transaction (an entry) was coined in the early days of databases, where commercial transactions were the main entries in databases. Although the data in databases are now different, the access pattern: looking up a few entries by key, inserting or updating data based on user input, remains the same and is referred to as online transaction processing (OLTP).

- Databases nowadays are also used for data analytics. The access pattern: scanning through the whole database and performing aggregation, is a very different from OLTP. This pattern is referred to as the online analytic processing (OLAP).

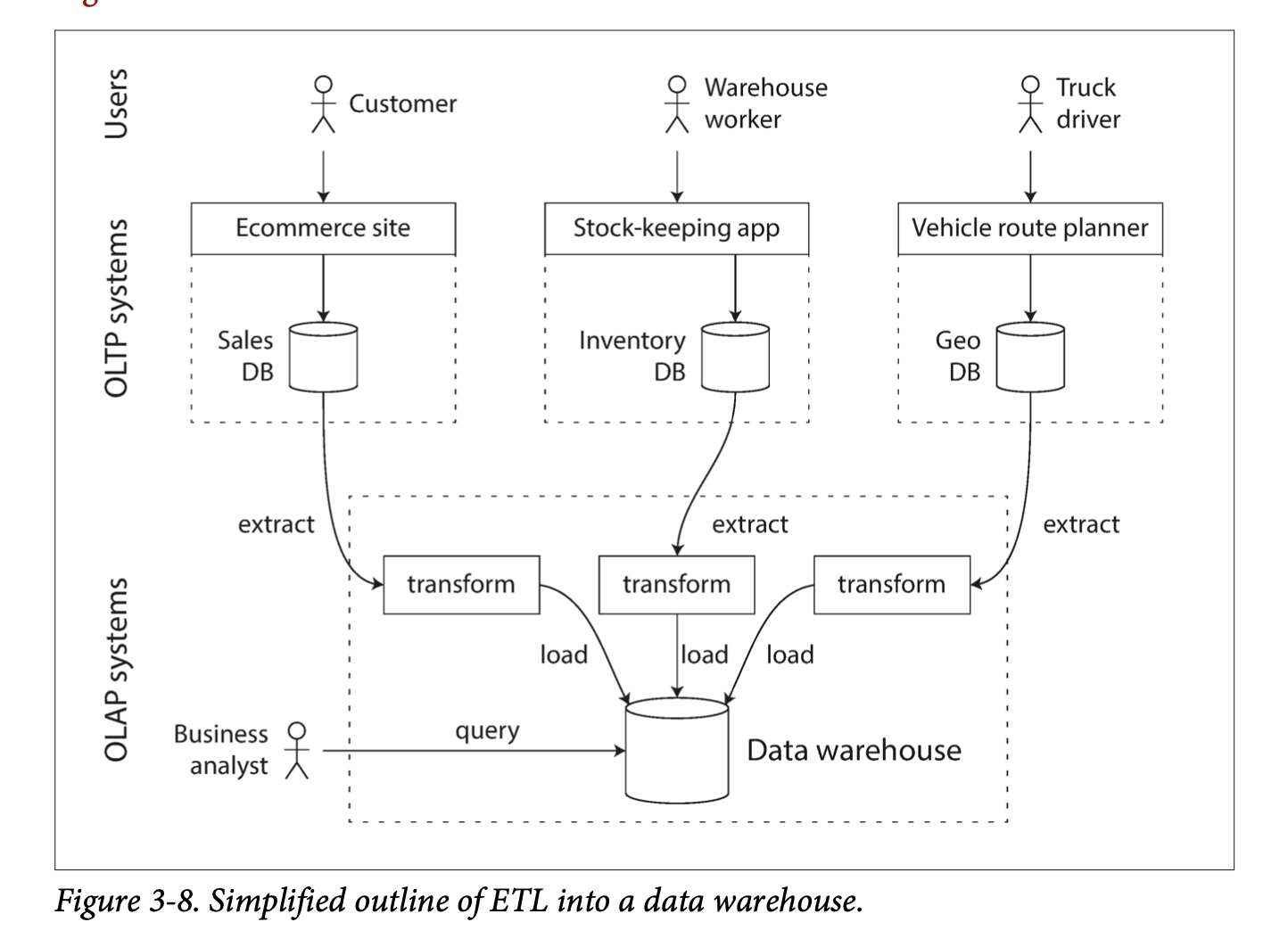

- Starting 1980s, people stopped using OLTP systems for OLAP applications. The data for analytics is hosted in a separate database - a data warehouse.

- OLTP is expected to be highly available with low latency, so it is not ideal to run analytics on OLTP databases.

- A data warehouse contains a read-only copy of the data in OLTP systems through periodic dumps or stream of updates.

- The process of getting data from OLTP systems to data warehouses is called Extract-Transform-Load (ETL).

- Data warehouses, separate from OLTP systems, can be optimized for analytics access patterns.

- The indexing algorithms mentioned above are for OLTP systems, not analytics.

- Although most data warehouses use a relational data model, the internals of the systems is very different as they are optimized for different access patterns.

- Although some products combines OLTP with data warehousing (Microsoft SQL, SAP HANA), they are increasingly becoming two separate systems.

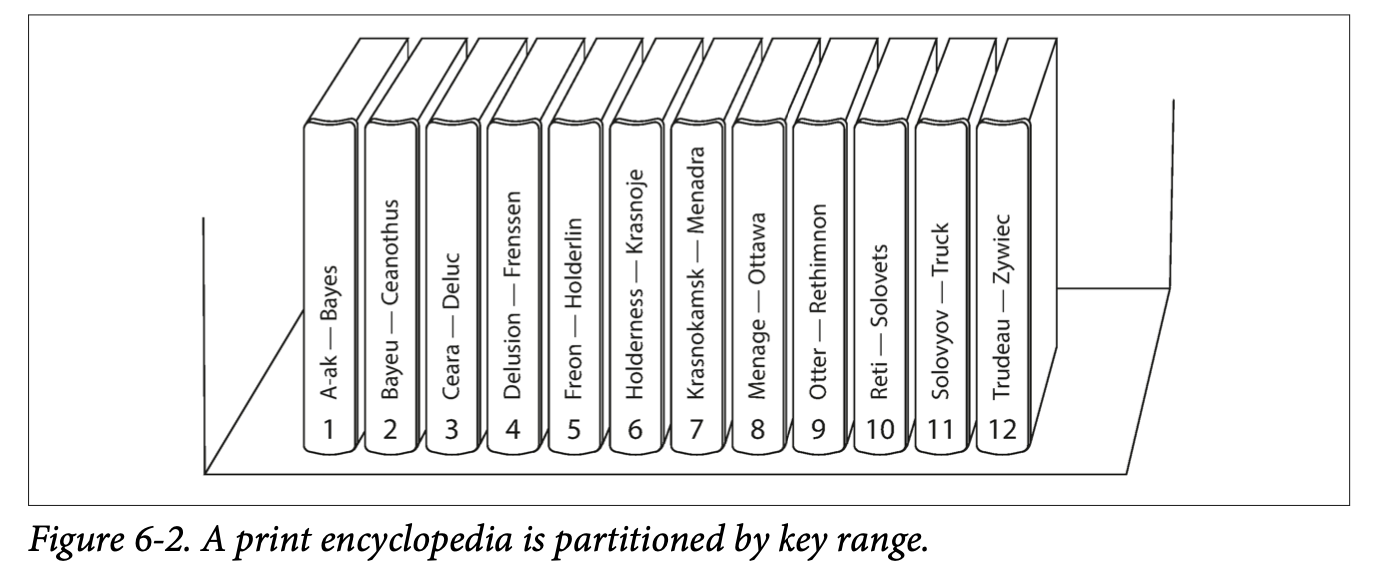

- Many data warehousing systems uses a star-schema, whose center is a fact table, where each row represents an event. The fact table uses foreign keys to refer to other tables (called dimension tables) for entities (with extra information) that was involved in the event.

- The snowflake schema further breaks dimensions down into sub-dimensions. Snowflake schemas are more normalized than star schemas, but star schemas are easier for analysts to work with.

- A typical data warehouse, tables could be very wide (up to several hundred columns), and dimension tables could also be very wide.

- A typical data warehouse query only access several rows.

- In most OLTP and document databases, storage is laid out in a row-oriented fashion, meaning all data from one row are stored next to each other. This is inefficient for queries which only accesses a few columns of all rows. The whole row will have to be read and filtered down to the columns of interest.

- In column-oriented storage, data of all rows from each column are stored together. It relies on each file containing the rows in the same order.

- Column-oriented storage often lends itself to good compression.

- Bitmap encoding of distinct values in a column can lead to good compression. Further, if the bitmap is sparse, we can use run-length encoding for more compression.

- Bitmap indexes are good for “equal” and “contain” queries.

- Although storing column in insertion order is easy, we can choose to sort them based on what queries are common.

- The administrator can specify a column for the database to be sorted in as well as a second column to break ties.

- The sorted columns would be much easier to compress if there are not a lot of distinct values in the column.

- Since data warehouse usually store multiple copies of the same data, it could use a different sort order for each replication, so that we can use different datasets for different queries.

- An analogy of multiple sorted orders to row-based databases is multiple secondary indexes. The difference is that row-based databases stores the data in one place and use pointers in secondary indexes, while column stores don’t use any pointers.

- Sorted columns optimizes for read-only queries, yet writes are more difficult.

- In-place updates would require rewriting the whole column on every write. Instead, we can use a LSM-tree like structure where a in-memory store buffers the new writes. When enough new writes are accumulated, they are then merged with the column files and written to new files in bulk.

- Queries, in this case, would require reading data from both disk and the in-memory store. This will be hidden within the engine and invisible to the user.

- Since many queries involves aggregation functions, a data warehouse can cache materialized aggregates to avoid recomputing expensive queries.

- One way of creating such a cache is a materialized view, which is defined like a standard view, but with results stored on disk, while virtual views are expanded and processed at query time.

- Updating materialized view, when data changes, is expensive, and therefore materialized views are not used in OLTP systems often.

- A common special case of materialized view is a data cube or OLAP cube, where data is pre-summarized over each dimension. This enables fast queries with precomputed queries, yet a data cube may not have the flexibility as raw data.

- Evolvability is important for maintainability in the long term, as applications inevitably change over time.

- Relational databases ensures all data conforms to the same format. The schema can be changed, but there is always only one schema.

- Schema-on-read databases can contain data a mix of data with older and newer formats.

- For larger applications, schema updates often cannot happen at the same time:

- Server side application can perform rolling-upgrade: a few nodes are updated at a time. No service downtime required.

- Client side application depends entirely on the user.

- This means old and new versions of the code and data may exist at the same time.

- We define backward compatibility as: newer code can read data written by older code. This is usually easier.

- We define forward compatibility as: older code can read data written by newer code. This could be tricker.

- Data usually are in one the following two representation:

- In memory, data is kept in objects, structs, list, arrays, hash tables, trees, etc. Those data structures are optimized for efficient access and manipulation.

- When data is written to a file or sent over the network, data are encoded into a sequence of bytes.

- Translating from in-memory representation to a byte sequence is called encoding, serialization, or marshalling. The revers is called decoding, parsing, deserialization, unmarshalling. This book uses the terms encoding and decoding.

- Java has Serializable, Ruby has Marshal, python has pikle and so on. Although language-specific formats comes with built-in support and are convenient, they have a few issues.

- Encoding is tied to a specific programming language, and cross-language reads are difficult. Migration to another language could be very expensive.

- Decoding needs to be able to instantiating arbitrary classes, which could be a security problem.

- Versioning is often an afterthought, and forward and backward compatibility is generally overlooked.

- Efficiency is often an afterthought. Java's serialization is notorious for bad performance and bloated encoding.

- TLDR. Don’t use them.

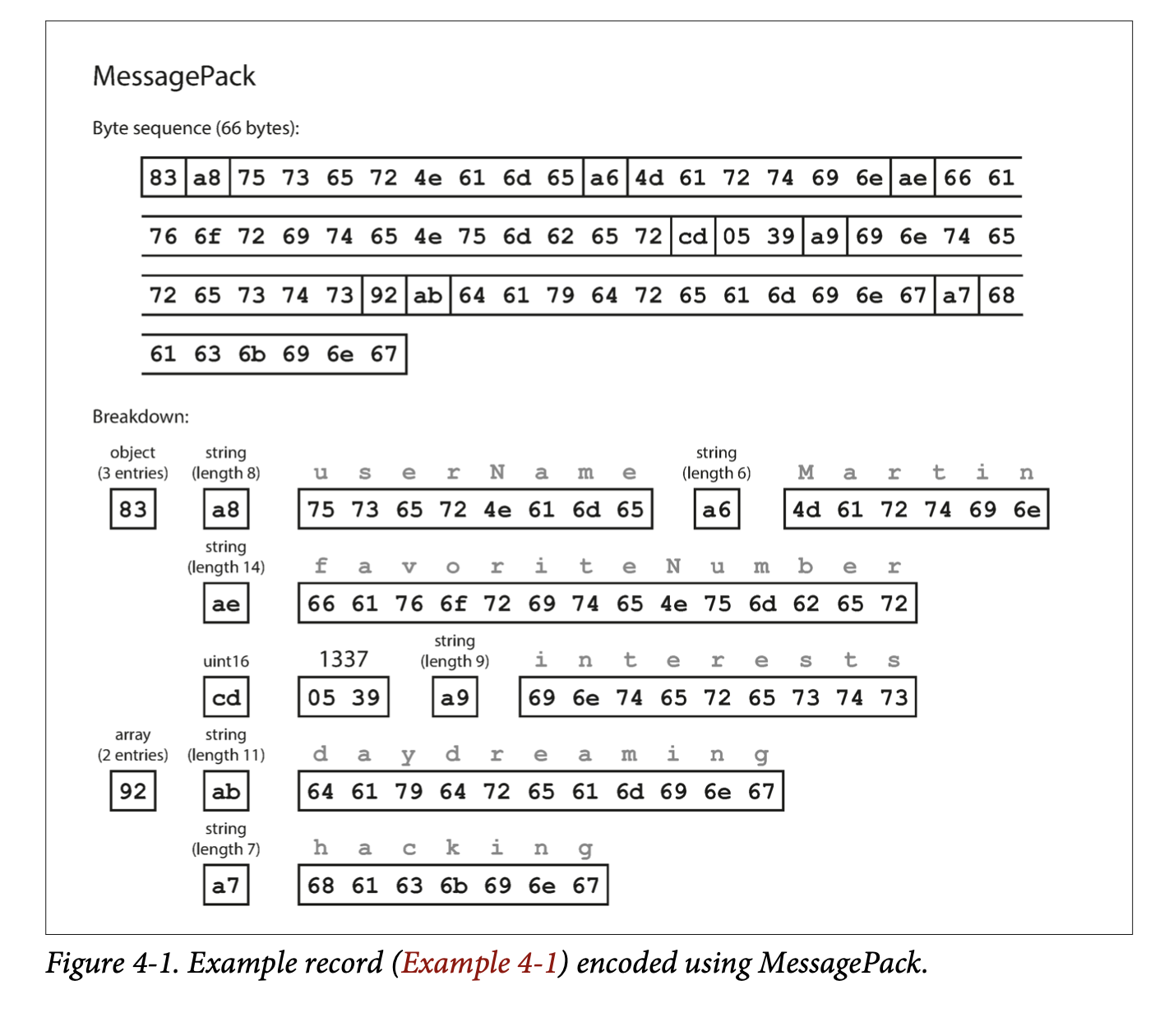

- JSON, XML, CSV are textual formats and somewhat human readable, yet they have the following problems:

- There is a lot of ambiguity around encoding of numbers. In XML and CSV, a numeric string and a number are the same. JSON doesn’t distinguish integers and floating-point numbers. Also, integers greater than 2^53 cannot be exactly represented by a IEEE 754 double-precision floating-point number.

- JSON and XML support Unicode character strings well but they don’t support binary strings.

- While there is schema support for XML and JSON, many JSON-based tools don’t use schemas. Applications that don’t use schemas need to hardcode the encoding and decoding logic.

- CSV does not have a schema, so encoding and decoding logic will have to be hardcoded. Also, not all CSV parsers handles escaping rules correctly.

- Despite the flaws, XML, JSON, and CSV are good enough for many purposes as long as application developers agree on the format.

- For bigdata, the efficiency of encoding can have a larger impact.

- Binary formats for JSON and XML have been developed but only adopted in niches.

- Those binary representation usually keep the data model unchanged and keeps field names within the encoded data.

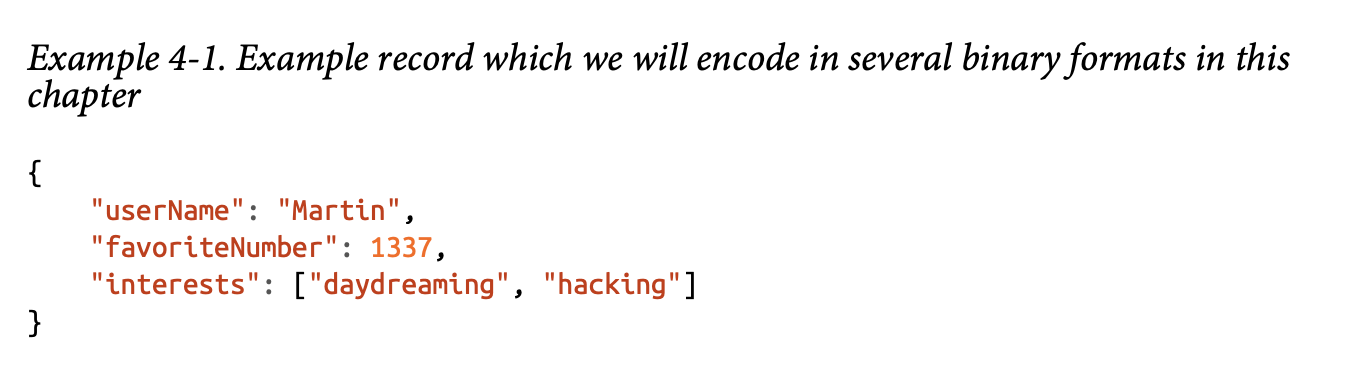

- The book gave a MessagePack example where the data was compressed from 81 bytes to 61 bytes.

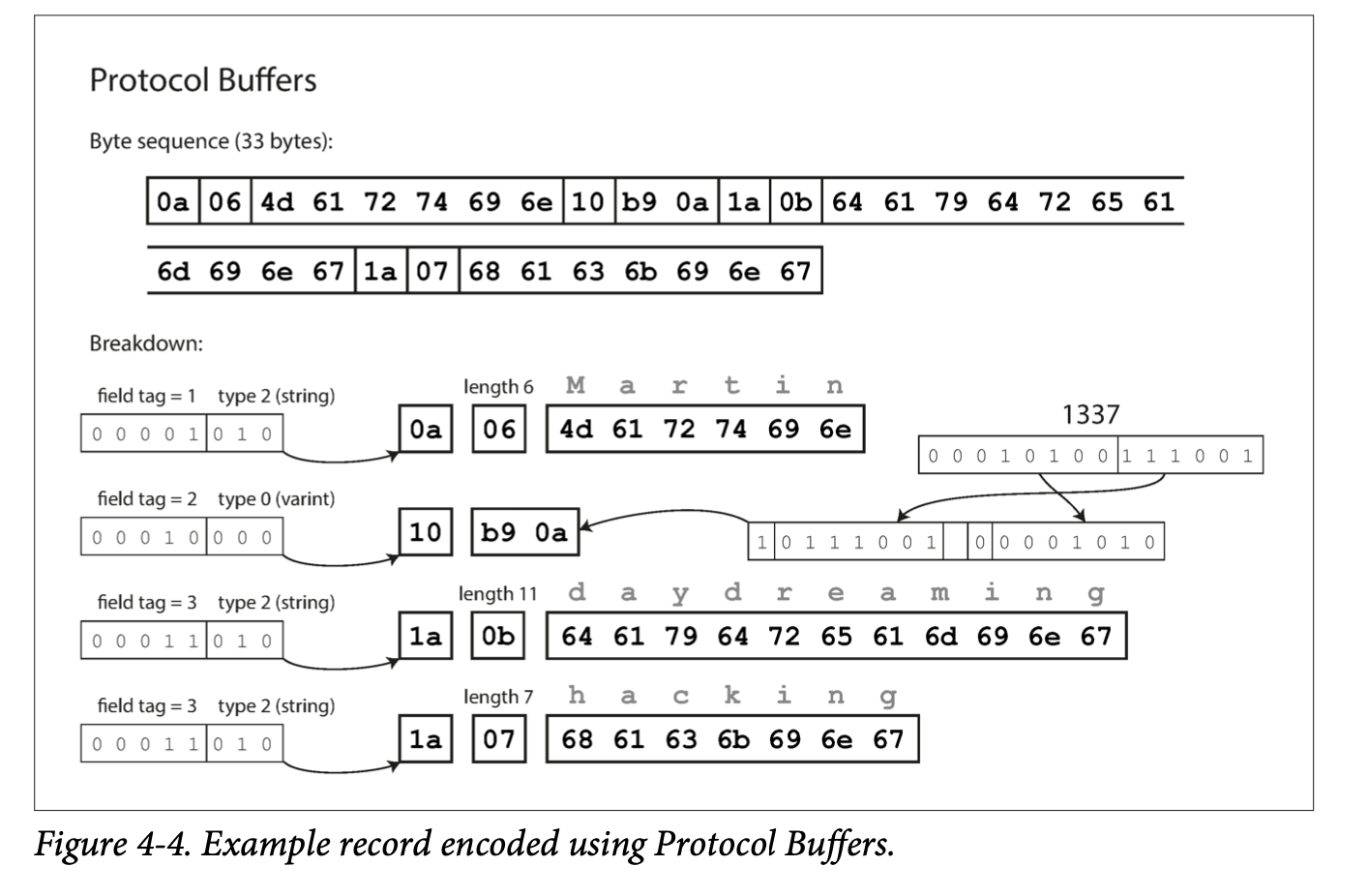

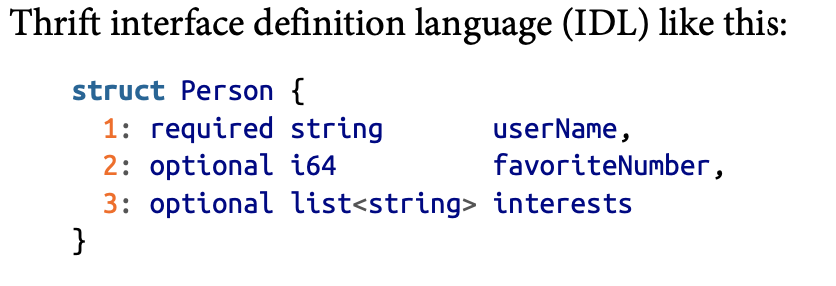

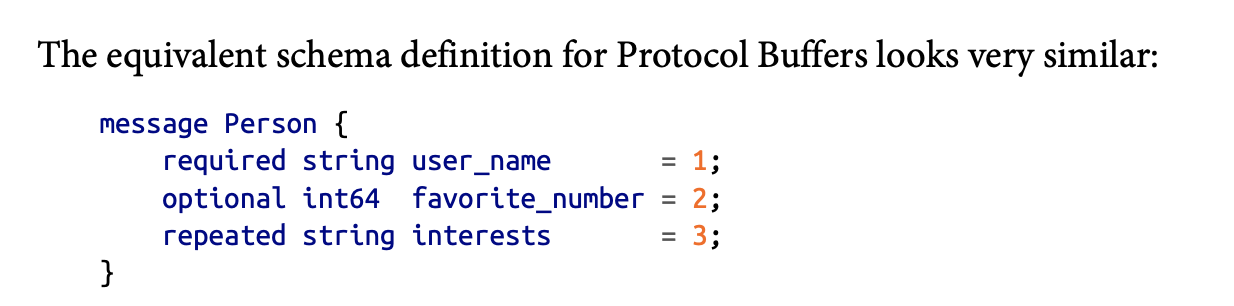

- Thrift and Protocol Buffers (protobuf) require a schema for encoding and decoding. They have their own schema definition language, which can then be use to generate code for multiple languages.

- Since Thrift and Protocol Buffers encodes the schema in code, the encoding does not need the field names but only field tags (positive integers).

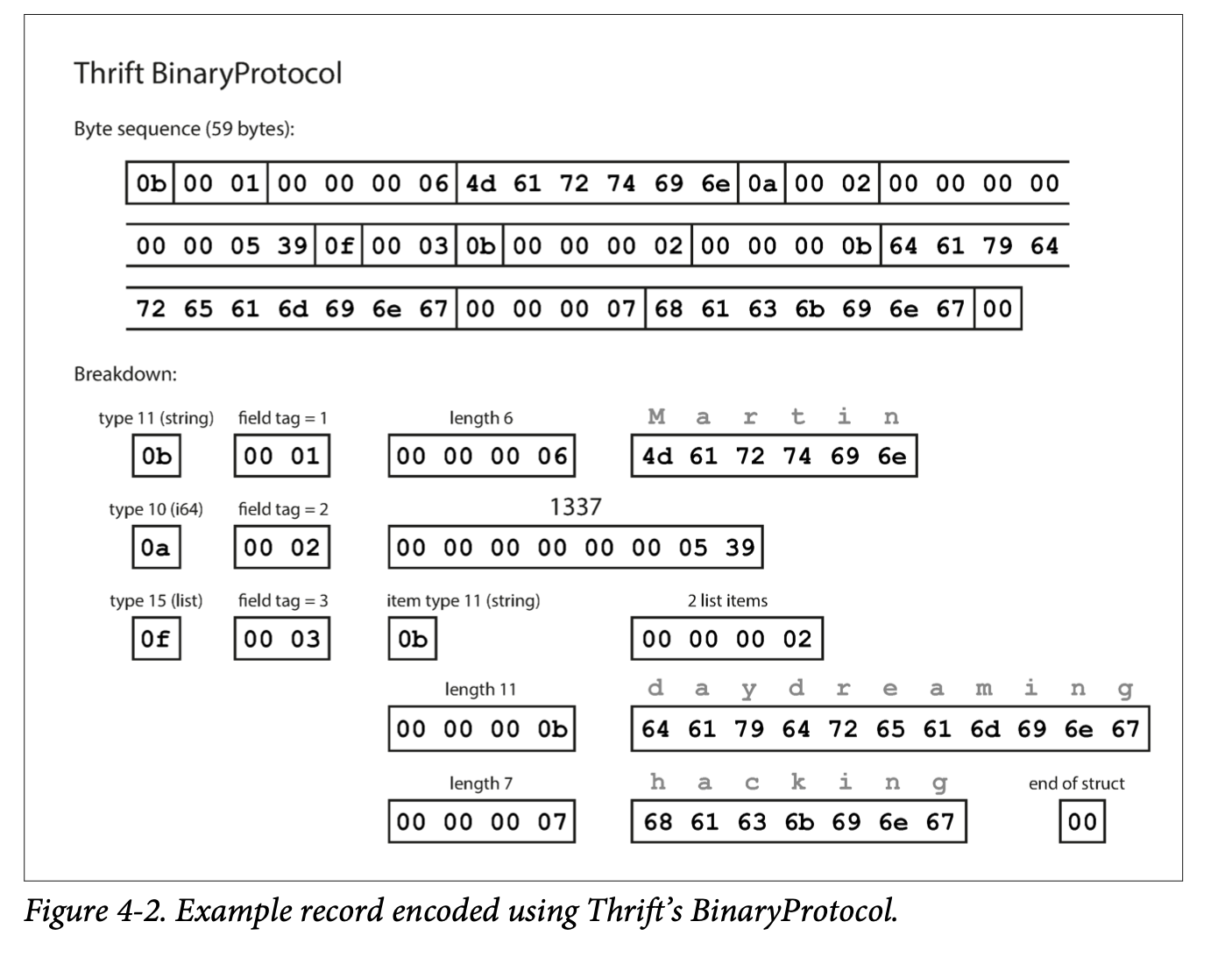

- Thrift has two binary encoding formats: BinaryProtocol and CompactProtocol. CompactProtocol packs field type and tag number into a single byte and uses variable length encoding for integers.

- Thrift and Protocol Buffers allow a field to be optional, yet the actual binary encoding does not have this information. The difference is only at run-time, where read a missing required field would result in an exception.

- Each field in Thrift and Protocol Buffers has a tag number and a data type. Since each field is identified only by the field tag, the name can be changed and the field tag number cannot be changed.

- For forward compatiblility, old code can simply skip the fields with unknown tags. For backward compatibility, as long as the newly added field is optional, new code can read data without the new optional field without throwing exceptions.

- Changing datatypes is trickier. Changing a 64-bit integer to 32-bit integer would lose precision or get truncated.

- Protocol Buffers does not have a list or array datatype, but has a repeated marker for fields that can appear multiple times. It is okay to change an optional field into a repeated field. New code sees a list of zero or one elements; old code reading new data sees the last element in the list. Thrift does not have this flexibility.

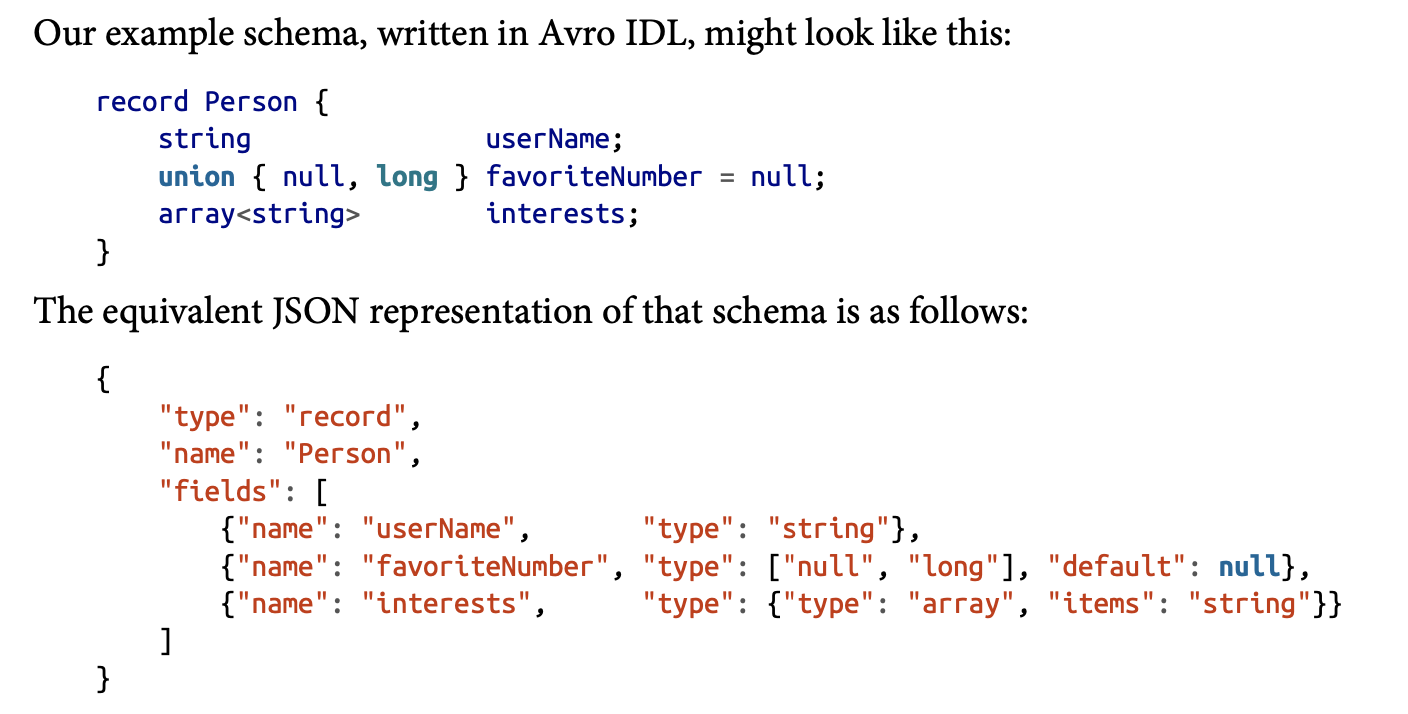

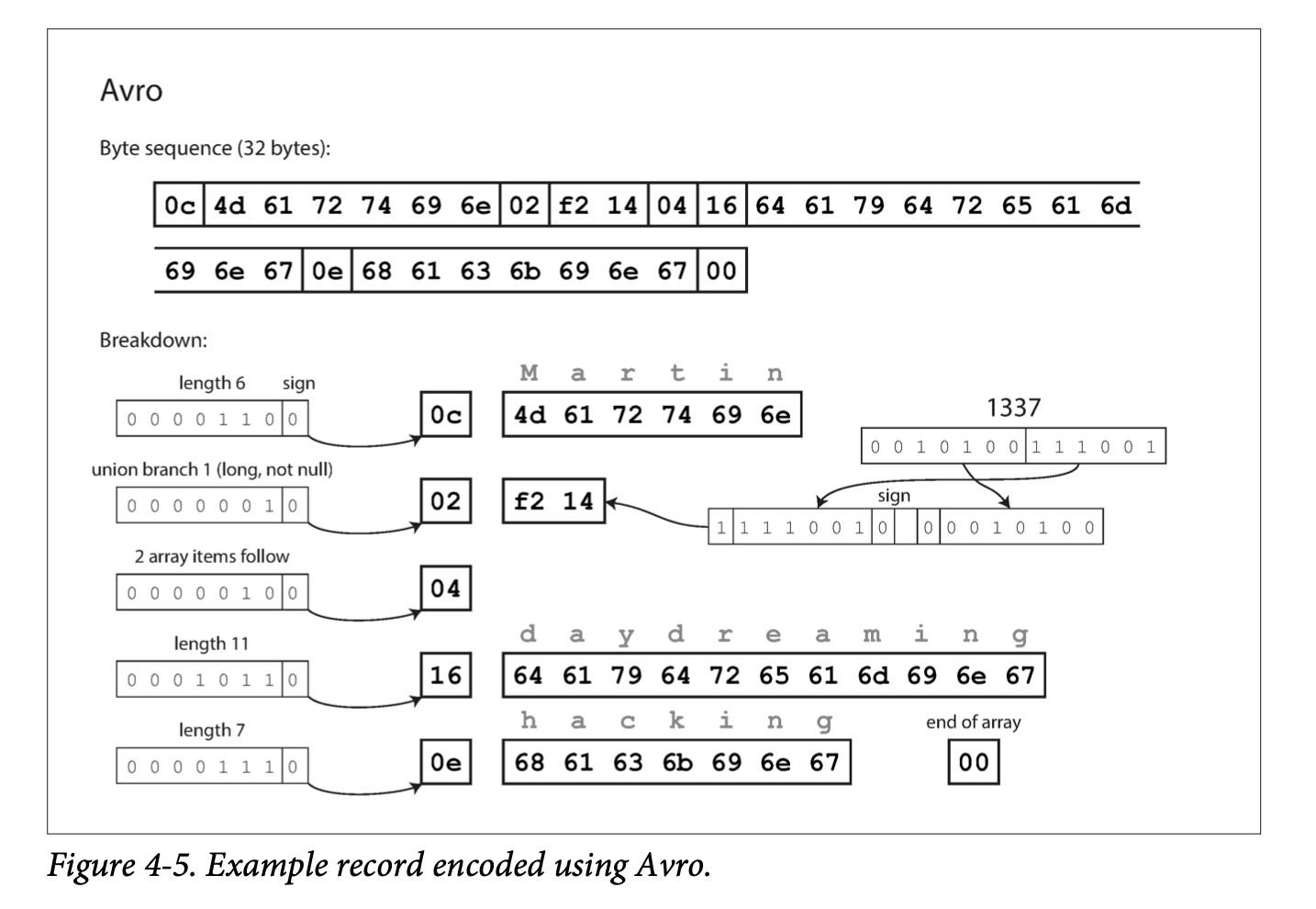

- Arvo has two schema languages, one Arvo IDL for human editing and one JSON based that is more machine-readable.

- There are no tag numbers in the schema. The encoding is a concatenation of field values.

- Arvo supports schema evolvability by keeping track of the writer’s schema and compare it with the reader’s schema.

- The reader’s and writer’s schema don’t have to be the same but only have to be compatible.

- To maintain compatibility, one can only add or remove a field with a default value.

- Note that Arvo does not allow nulls to be a default value unless a union type, which includes a null, is the type of the field. As a result, Arvo does not have optional and required.

- Changing the datatype is possible as long as Arvo can convert the type. Changing the name of the field is done by adding aliases of field names, so a new reader’s schema can match old writer’s schema. Note this is only backward compatible, not forward compatible.

- Since it is inefficient to encode the writer’s schema with each data entry, how the writer’s schema is handled depends on the context.

- Storing many entries of the same schema: the writer’s schema can be written once at the beginning of the file.

- Database with individually written records: one can include a version number for each record and store a map of schema version to schema in a separate database.

- Sending data over a network: The schema can be negotiated during the connection setup time if the communication is bidirectional.

- A database of schema versions is a useful thing that can also be used as a documentation of the evolution history.

- Since Arvo does not use tags for fields, it is friendlier to dynamic generated schemas. No code generation is required when the schema changes. For example, if we have an application that dumps relational database contents to disk, we do not need to perform code generation a new schema every time the database adds a new field.

- Code generation is more aligned with statically typed languages as it allows efficient in-memory structures to be used for decoded data, and it allows type checking and autocompletion in IDEs. However, for dynamically typed languages code generation becomes a burden, as they usually avoid an explicit compilation step.

- Arvo provides optional code generation for statically typed languages, but it can be used without any code generation as long as you have the writer’s schema. This is especially useful for working with dynamically typed data processing languages.

- Compared to JSON, XML, and CSV, formats with a schema, such as Protocol Buffer, Thrift, and Arvo have the following good properties:

- They are simpler to implement.

- They are much more compact.

- The schema is a form of documentation.

- Keeping a database of schemas allows one to check forward and backward compatibility before anything is deployed.

- Automatic code generation for statically typed languages.

- The most common ways of how data flows between applications are:

- through database,

- through service calls,

- and through asynchronous message passing.

- Data can be sent from one application to a different application or the application’s future self through databases.

- A process that writes to a database encodes the data, and a process that reads data from a database decodes the data.

- Both backward and forward compatibility are required here.

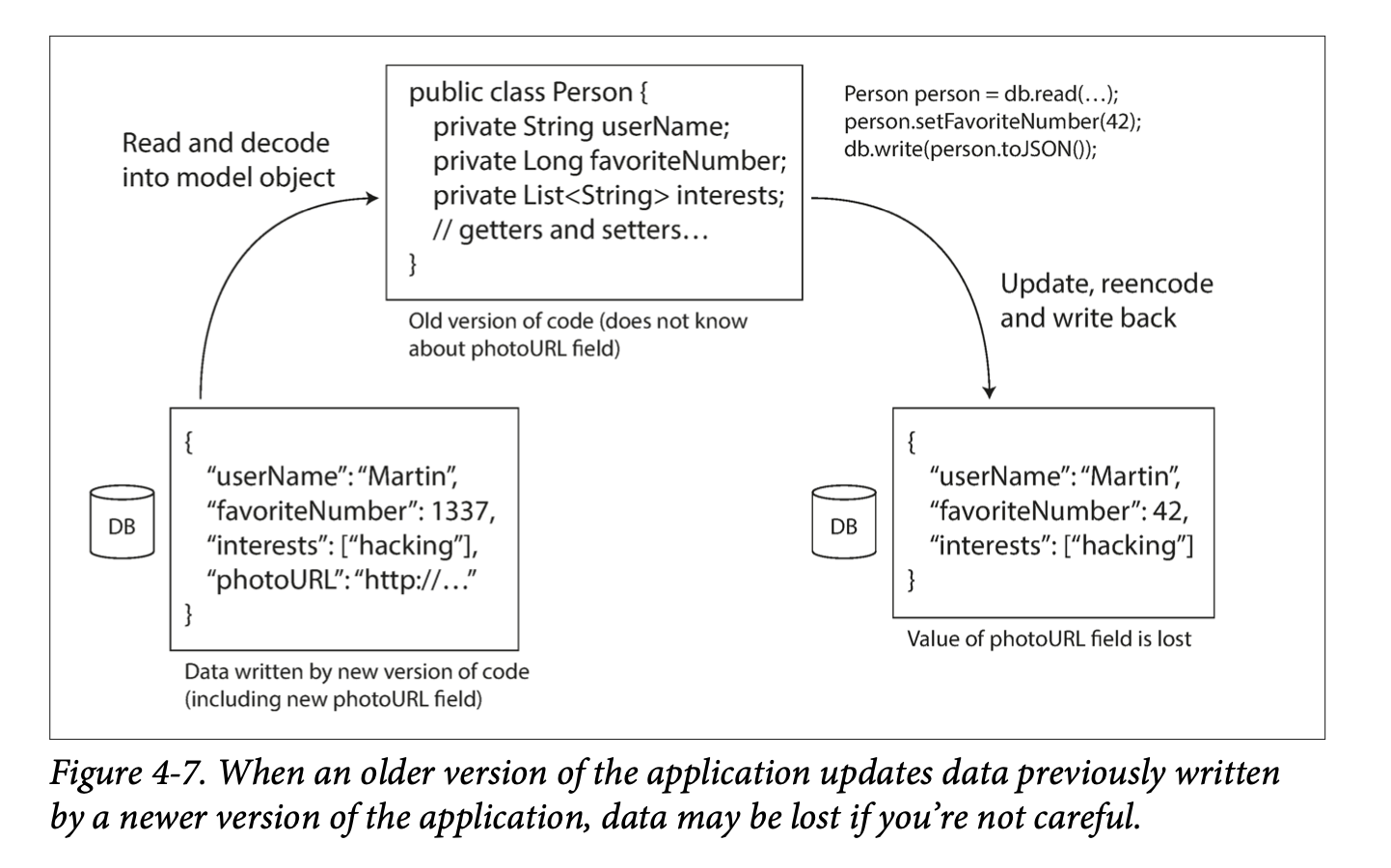

- An old process reading and writing a record of new data will need to preserve the unknown fields.

- Databases may persist data for years, and it is common that data outlives code.

- Rewriting (migrating) is expensive, most relational databases allow simple schema changes, such as adding a new column with a null default value without rewriting existing data. When an old row is read, the database fills in nulls for any columns that are missing.

- Schema evolution allows the entire database to appear as if it was encoded with a single schema, even if the binary format was encoded with different versions of the schema.

- Avro has sophisticated schema evolution rules that can allow a database to appear as if was encoded with a single schema, even though the underlying storage may contain records encoded with previous schema versions.

- When taking a snapshot or dumping data into a data warehouse, one can encode all data in the latest schema.

- Data can be sent from a one application (client) to another application (server) through network over the API (service) the server exposes.

- HTTP is the transport protocol and is independent of the server-client agreement of the API.

- A few examples of clients:

- Web browsers retrieves data using HTTP GET requests and submits data through HTTP POST requests.

- A native application could also make requests to a server and a client-side JavaScript application can use XMLHttpRequest to become an HTTP client (Ajax). In this case the response is usually not human readable but for further processing by the client.

- A server can be a client of another service. Breaking down a monolithic service into smaller services is referred to as the microservices architecture or service-oriented architecture.

- The goal for microservices architecture is to make each subservice independently deployable and evolvable. Therefore, we will need both forward and backward compatibility for the binary encodings of data.

- When HTTP is used as the protocol for talking to the service, it is called a web service, for example:

- A client application making requests to a service over HTTP over public internet.

- A service making requests to services within the same organization. Software that supports such services is sometimes called middleware.)

- A service making requests to services owned by a different organization.

- There are two approaches for designing the API for web services REST and SOAP.

- REST uses simple data formats, URLs for identifying resources, and HTTP features for cache control, authentication and content type negotiation. APIs designed based on REST principles are called RESTful.

- SOAP is a XML-based protocol. While it uses HTTP, it avoids using HTTP features. SOAP APIs are described using Web Services Description Language (WSDL), which enables code generation. WSDL is complicated and requires tool support for constructing requests manually.

- REST has been gaining popularity.

- The RPC model treats a request to a remote network service the same as a calling a function within the same process (this is called location transparency.) This approach has the following issues:

- A network request is more unpredictable than a local function call.

- A local function call returns a result, throws an exception, or never returns, but a network call may return without a result, due to a timeout.

- Retrying a failed network request is not the right solution, as the request could have gone through, but the response was lost.

- The run time for the function is unpredictable.

- Passing references to objects in local memory requires encoding the whole object and could be expensive for large objects.

- The client and server may be implemented in different languages, so the framework must handle the datatype translations.

- The new generation of RPC frameworks is more explicit about the fact that a remote call is different from a local call, e.g., Finagle and Rest.li use futures (promises) to encapsulate asynchronous actions that may fail. Some of those frameworks provide service discovery to allow clients to find out which IP address and port number it can find a particular service.

- Custom RPC protocols with binary encoding can achieve better performance than JSON over REST, but RESTful APIs are easier to test and is supported by all mainstream programming languages.

- We can assume the server will always be updated before the clients, so we only need backward compatibility on requests and forward compatibility on responses.

- The compatibilities of a RPC scheme are directly inherited by the binary encoding scheme it uses.

- RESTful APIs usually uses JSON for responses or URI-encoded/form-encoded for requests. Therefore, adding optional new request parameters or response fields maintains compatible.

- For public APIs, the provider has no control over its clients and will have to maintain them for a long time.

- There is no agreement on how API versioning should work. For RESTful APIs, common approaches are to use a version number in the URL or in the HTTP Accept header.

- Asynchronous message-passing systems are somewhere between RPC and databases. Data is sent from a process to another process with low latency through a message broker, which stores the message temporarily.

- Using a message broker, compare to direct RPC, the advantages are:

- It can act as a buffer to improve reliability.

- It can redeliver messages to a process that has crashed.

- The sender does not need to know the IP or port of the recipient.

- It allows one message to be sent to multiple receivers.

- It decouples the sender and receiver.

- The communication is one-way and asynchronous. The sender doesn’t wait for the response from the receiver.

- Message brokers are used as follows. The producer sends a message to a named queue or topic, and the broker ensures the message is delivered to the consumers or subscribers of that queue or topic. There could be many producers and consumers on the same topic.

- Ideally the messages should be encoded by a forward and backward compatible scheme. If a consumer republishes a message to another topic, it may need to preserve unknown fields.

- The actor model is a programming model for concurrency in a single process. Each actor may have its own state and communicates with other actors through sending and receiving asynchronous messages.

- In distributed actor frameworks, the actor model is used to scale an application across multiple nodes. The same message-passing mechanism is used.

- Location transparency works better in the actor model than RPC, since the model already assumes the messages could be lost.

- Three popular distributed actor frameworks: Akka, Orleans, Erlang OPT.

- Reasons for replication:

- Store data closer to users to reduce latency.

- Improve availability.

- Scale throughput

- The challenge is not storing the data, but handling changes to replicated data.

- There are three popular algorithms: single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication.

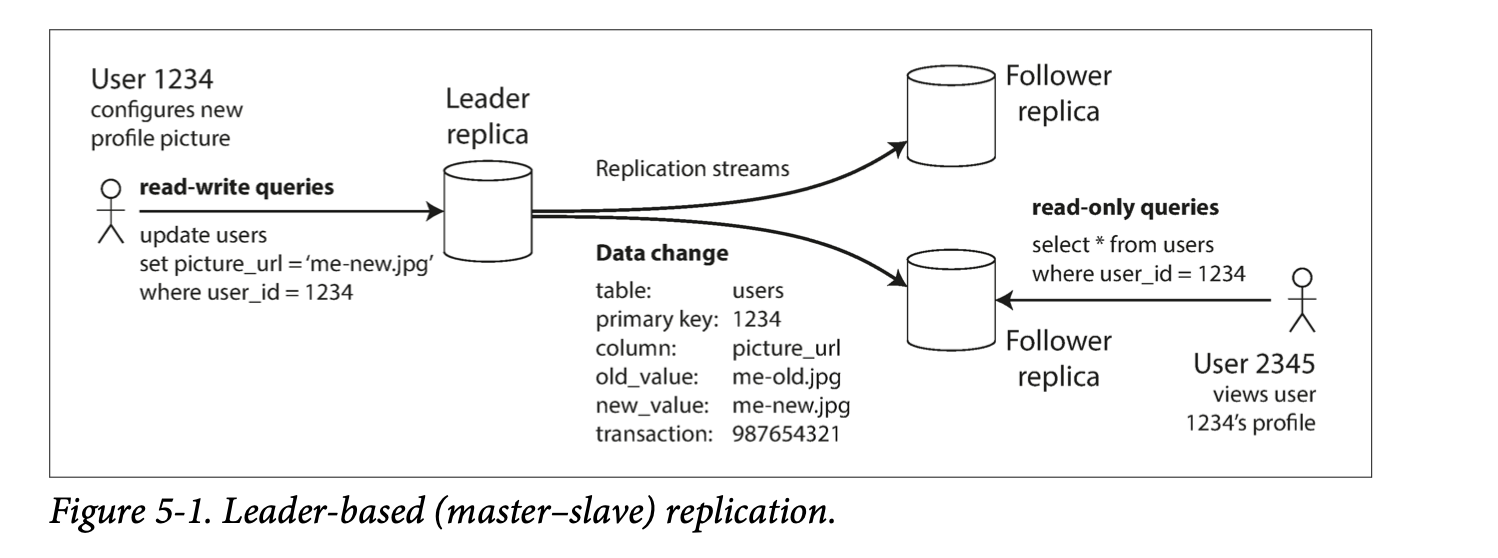

Every node that keeps a copy of data is a replica. Obvious question is: how do we make sure that the data on all the replicas is the same? The most common approach for this is leader-based replication. In this approach:

- Only the leader accepts writes.

- The followers read off a replication log and apply all the writes in the same order that they were processed by the leader.

- A client can query either the leader or any of its followers for read requests.

So here, the followers are read-only, while writes are only accepted by the leader. This approach is used by MySQL, PostgreSQL etc., as well as non-relational databases like MongoDB, RethinkDB, and Espresso.

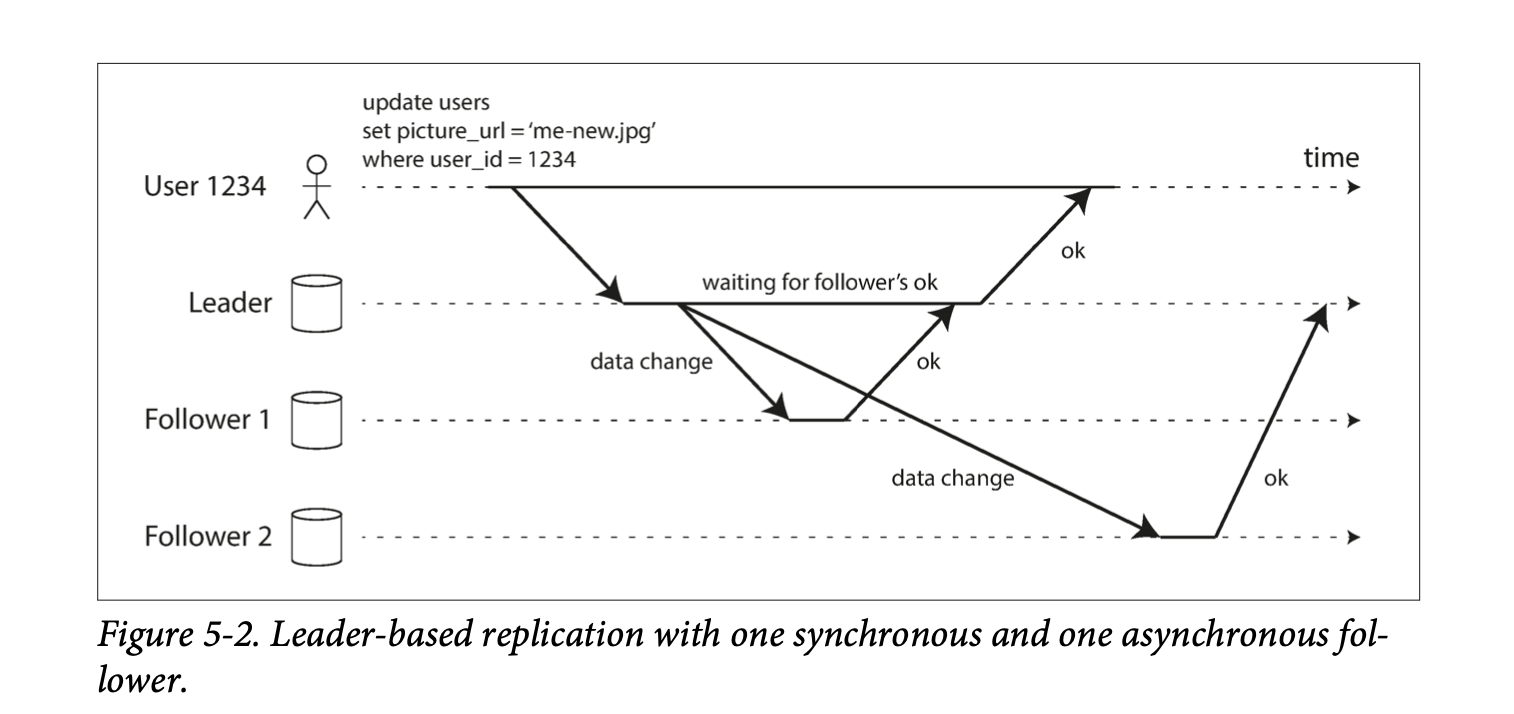

With Synchronous replication, the leader must wait for a positive acknowledgement that the data has been replicated from at least one of the followers before terming the write as successful, while with Asynchronous replication, the leader does not have to wait.

The advantage of synchronous replication is that if the leader suddenly fails, we are guaranteed that the data is available on the follower.

The disadvantage is that if the synchronous follower does not respond (say it has crashed or there's a network delay or something else), the write cannot be processed. A leader must block all writes and wait until the synchronous replica is available again. Therefore, it's impractical for all the followers to be synchronous, since just one node failure can cause the system to become unavailable.

In practice, enabling synchronous replication on a database usually means that one of the followers is synchronous, and the others are asynchronous. If the synchronous one is down, one of the asynchronous followers is made synchronous. This configuration is sometimes called semi-synchronous.

In this approach, if the leaders fails and is not recoverable, any writes that have not been replicated to followers are lost. An advantage of this approach though, is that the leader can continue processing writes, even if all its followers have fallen behind.

There's some research into how to prevent asynchronous-performance like systems from losing data if the leader fails. A new replication method called Chain replication is a variant of synchronous replication that aims to provide good performance and availability without losing data.

New followers can be added to an existing cluster to replace a failed node, or to add an additional replica. The next question is how to ensure the new follower has an accurate copy of the leader's data?

- Take a consistent snapshot of the leader's db at some point in time. It's possible to do this without taking a lock on the entire db. Most databases have this feature.

- Copy the snapshot to the follower node.

- The follower then requests all the data changes that happened since the snapshot was taken.

- When the follower has processed the log of changes since the snapshot, we say it has caught up. In some systems, this process is fully automated, while in others, it is manually performed by an administrator.

Any node can fail, therefore, we need to keep the system running despite individual node failures, and minimize the impact of a node outage. How do we achieve high availability with leader-based replication?

Each follower typically keeps a local log of the data changes it has received from the leader. If a follower node fails, it can compare its local log to the replication log maintained by the leader, and then process all the data changes that occurred when the follower was disconnected.

This is trickier: One of the nodes needs to be promoted to be the new leader, clients need to be reconfigured to send their writes to the new leader, and the other followers need to start consuming data changes from the new leader. This whole process is called a failover. Failover can be handled manually or automatically.

An automatic failover consists of:

- Determining that the leader has failed: Many things could go wrong: crashes, power outages, network issues etc. There's no foolproof way of determining what has gone wrong, so most systems use a timeout. If the leader does not respond within a given interval, it's assumed to be dead.

- Choosing a new leader: This can be done through an election process (where the new leader is chosen by a majority of the remaining replicas), or a new leader could be appointed by a previously elected controller node. The best candidate for leadership is typically the one with the most up-to-date data changes from the old leader (to minimize data loss)

- Reconfiguring the system to use the new leader: Clients need to send write requests to the new leader, and followers need to process the replication log from the new leader. The system also needs to ensure that when the old leader comes back, it does not believe that it is still the leader. It must become a follower.

There are a number of things that can go wrong during the failover process:

- For asynchronous systems, we may have to discard some writes if they have not been processed on a follower at the time of the leader failure. This violates clients' durability expectations.

- Discarding writes is especially dangerous if other storage systems are coordinated with the database contents. For example, say an autoincrementing counter is used as a MySQL primary key and a redis store key, if the old leader fails and some writes have not been processed, the new leader could begin using some primary keys which have already been assigned in redis. This will lead to inconsistencies in the data, and it's what happened to Github (https://github.blog/2012-09-14-github-availability-this-week/).

- In fault scenarios, we could have two nodes both believe that they are the leader: split brain. Data is likely to be lost/corrupted if both leaders accept writes and there's no process for resolving conflicts. Some systems have a mechanism to shut down one node if two leaders are detected. This mechanism needs to be designed properly though, or what happened at Github can happen again( https://github.blog/2012-12-26-downtime-last-saturday/)

- It's difficult to determine the right timeout before the leader is declared dead. If it's too long, it means a longer time to recovery in the case where the leader fails. If it's too short, we can have unnecessary failovers, since a temporary load spike could cause a node's response time to increase above the timeout, or a network glitch could cause delayed packets. If the system is already struggling with high load or network problems, unnecessary failover can make the situation worse.

Several replication methods are used in leader-based replication. These include:

In this approach, the leader logs every write request (statement) that it executes, and sends the statement log to every follower. Each follower parses and executes the SQL statement as if it had been received from a client.

A problem with this approach is that a statement can have different effects on different followers. A statement that calls a nondeterministic function such as NOW() or RAND() will likely have a different value on each replica. If statements use an autoincrementing column, they must be executed in exactly the same order on each replica, or else they may have a different effect. This can be limiting when executing multiple concurrent transactions, as statements without any causal dependencies can be executed in any order. Statements with side effects (e.g. triggers, stored procedures) may result in different side effects occurring on each replica, unless the side effects are deterministic. Some databases work around this issues by requiring transactions to be deterministic, or configuring the leader to replace nondeterministic function calls with a fixed return value.

The log is an append-only sequence of bytes containing all writes to the db. Besides writing the log to disk, the leader can also send the log to its followers across the network.

The main disadvantage of this approach is that the log describes the data on a low level. It details which bytes were changed in which disk blocks. This makes the replication closely coupled to the storage engine. Meaning that if the storage engine changes in another version, we cannot have different versions running on the leader and the followers, which prevents us from making zero-downtime upgrades.

This logs the changes that have occurred at the granularity of a row. Meaning that:

- For an inserted row, the log contains the new values of all columns.

- For a deleted row , the log contains enough information to identify the deleted row. Typically the primary key, but it could also log the old values of all columns.

- For an updated row, it contains enough information to identify the updated row, and the new values of all columns.

This decouples the logical log from the storage engine internals. Thus, it makes it easier for external applications (say a data warehouse for offline analysis, or for building custom indexes and caches) to parse. This technique is called change data capture.

This involves handling replication within the application code. It provides flexibility in dealing with things like: replicating only a subset of data, conflict resolution logic, replicating from one kind of database to another etc. Trigger and Stored procedures provide this functionality. This method has more overhead than other replication methods, and is more prone to bugs and limitations than the database's built-in replication.

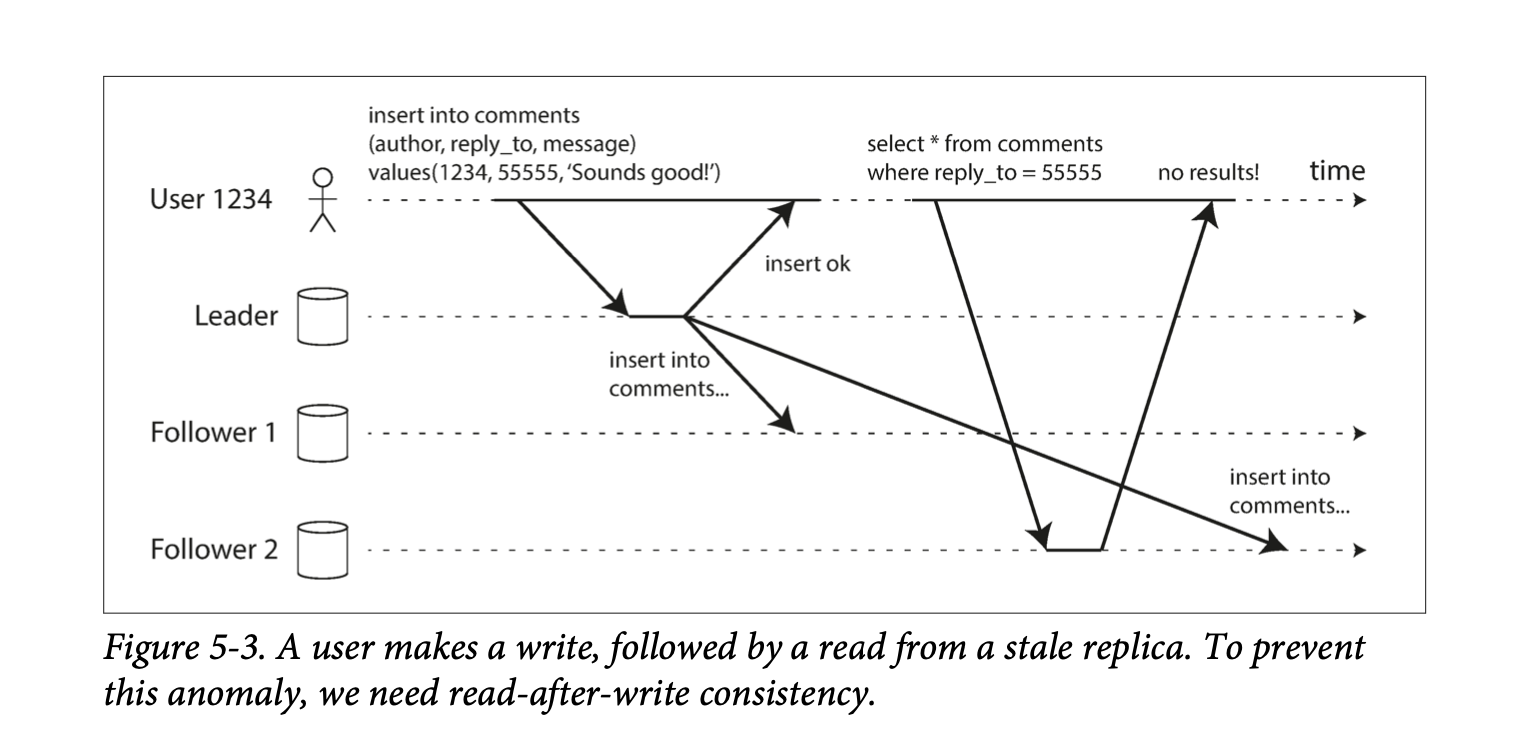

Eventual Consistency: If an application reads from an asynchronous follower, it may see outdated information if the follower has fallen the leader. This inconsistency is a temporary state, and the followers will eventually catchup. That's eventual consistency.

The delay between when a write happens on a leader and gets reflected on a follower is replication lag.

Other Consistency Levels There are a number of issues that can occur as a result of replication lag. In this section, I'll summarize them under the minimum consistency level needed to prevent it from happening.

Read-after-write consistency, also known as read-your-writes consistency is a guarantee that if the user reloads the page, they will always see any updates they submitted themselves.

How to implement it:

- When reading something that the user may have modified, read it from the leader. For example, user profile information on a social network is normally only editable by the owner. A simple rule is always read the user's own profile from the leader.

- You could track the time of the latest update and, for one minute after the last update, make all reads from the leader.

- The client can remember the timestamp of the most recent write, then the system can ensure that the replica serving any reads for that user reflects updates at least until that timestamp.

- If your replicas are distributed across multiple datacenters, then any request needs to be routed to the datacenter that contains the leader. Another complication is that the same user is accessing your service from multiple devices, you may want to provide cross-device read-after-write consistency.

Some additional issues to consider:

- Remembering the timestamp of the user's last update becomes more difficult. The metadata will need to be centralised.

- If replicas are distributed across datacenters, there is no guarantee that connections from different devices will be routed to the same datacenter. You may need to route requests from all of a user's devices to the same datacenter.

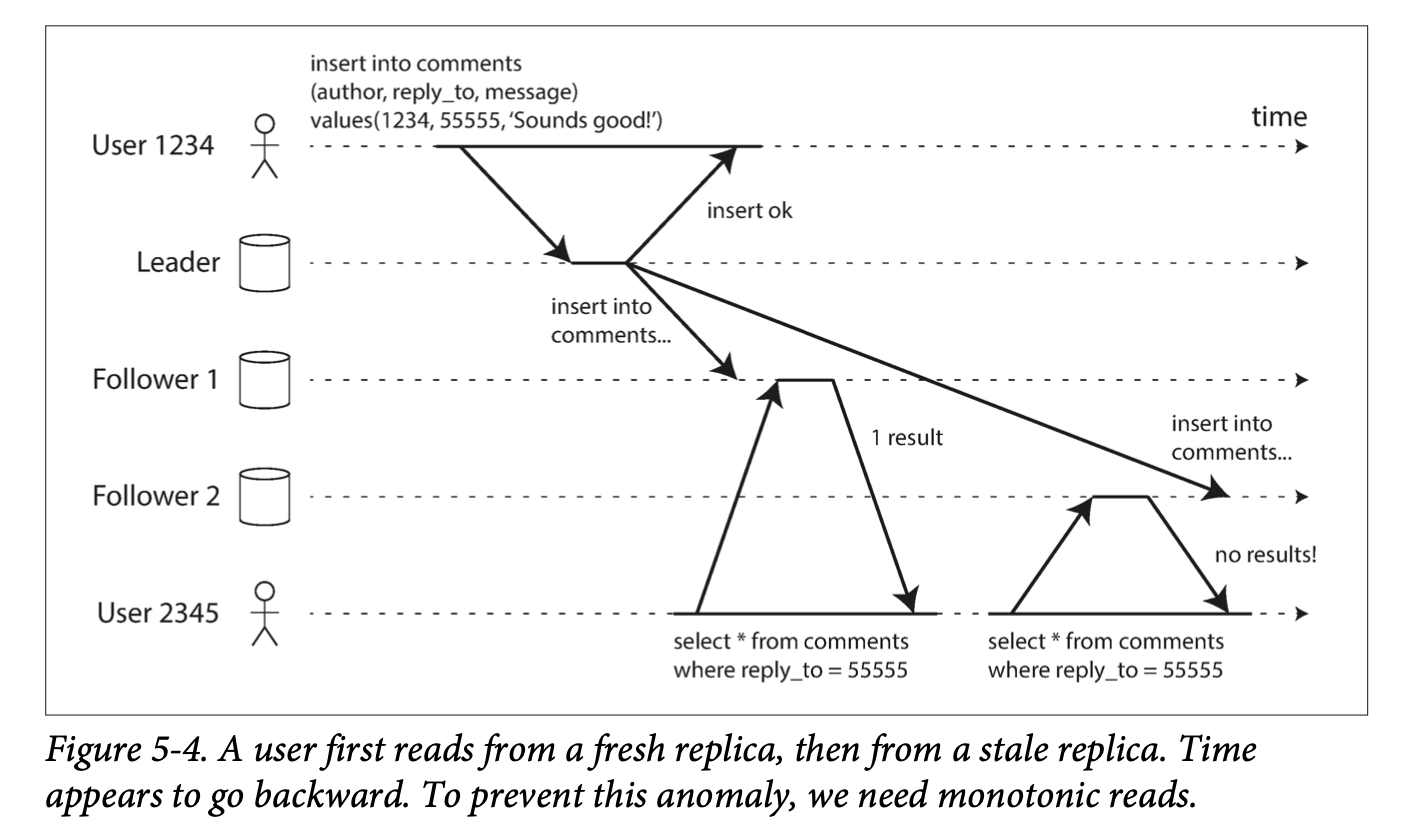

Because of followers falling behind, it's possible for a user to see things moving backward in time.

When you read data, you may see an old value; monotonic reads only means that if one user makes several reads in sequence, they will not see time go backward.

Make sure that each user always makes their reads from the same replica. The replica can be chosen based on a hash of the user ID. If the replica fails, the user's queries will need to be rerouted to another replica.

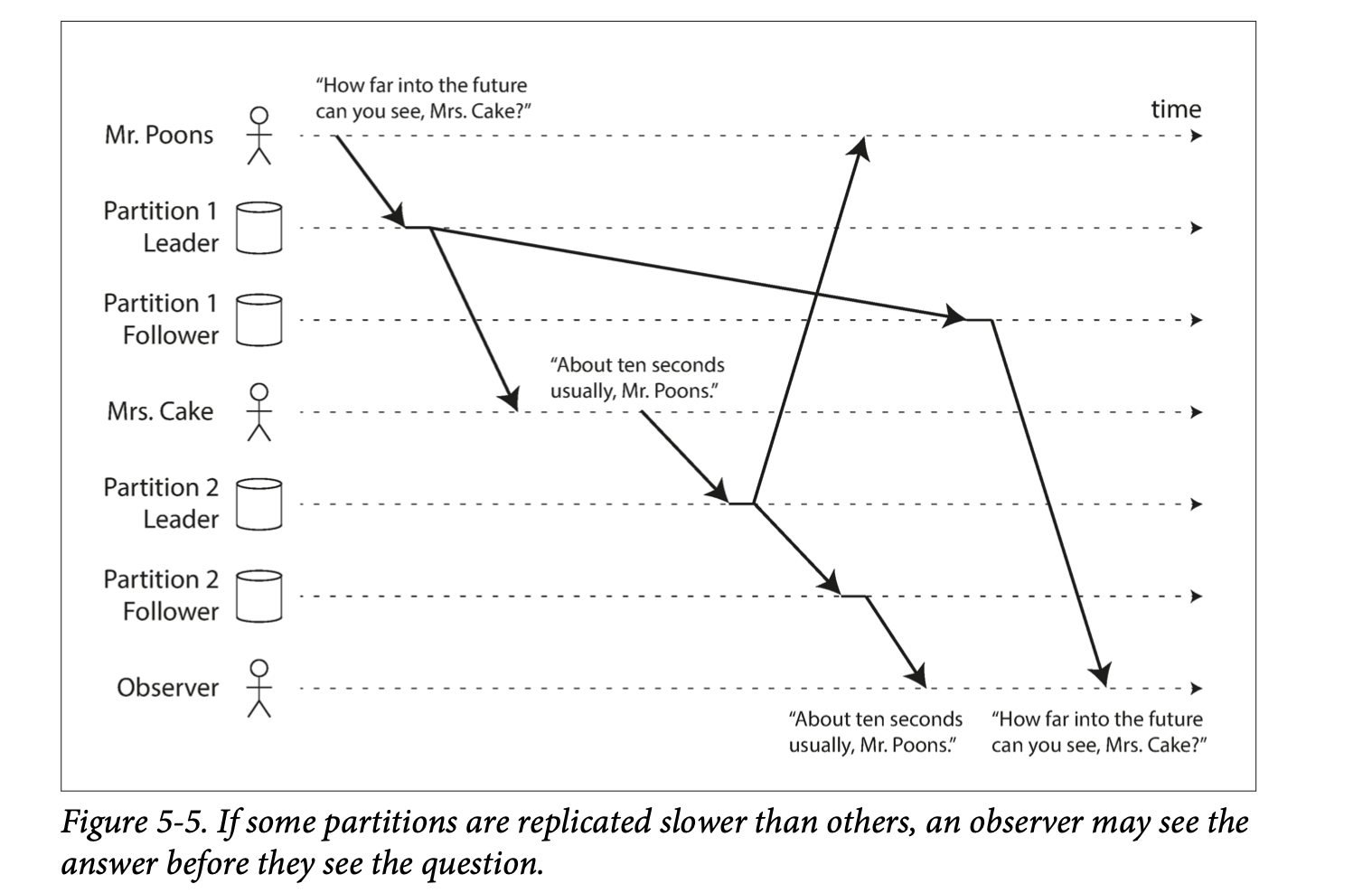

Another anomaly that can occur as a result of replication lag is a violation of causality. Meaning that a sequence of writes that occur in one order might be read in another order. This can especially happen in distributed databases where different partitions operate independently and there's no global ordering of writes. Consistent prefix reads is a guarantee that prevents this kind of problem.

One solution is to ensure that causally related writes are always written to the same partition, but this cannot always be done efficiently.

Application developers should ideally not have to worry about subtle replication issues and should trust that their databases "do the right thing". This is why transactions exist. They allow databases to provide stronger guarantees about things like consistency. However, many distributed databases have abandoned transactions because of the complexity, and have asserted that eventual consistency is inevitable. Martin discusses these claims later in the chapter.

The downside of single-leader replication is that all writes must go through that leader. If the leader is down, or a connection can't be made for whatever reason, you can't write to the database.

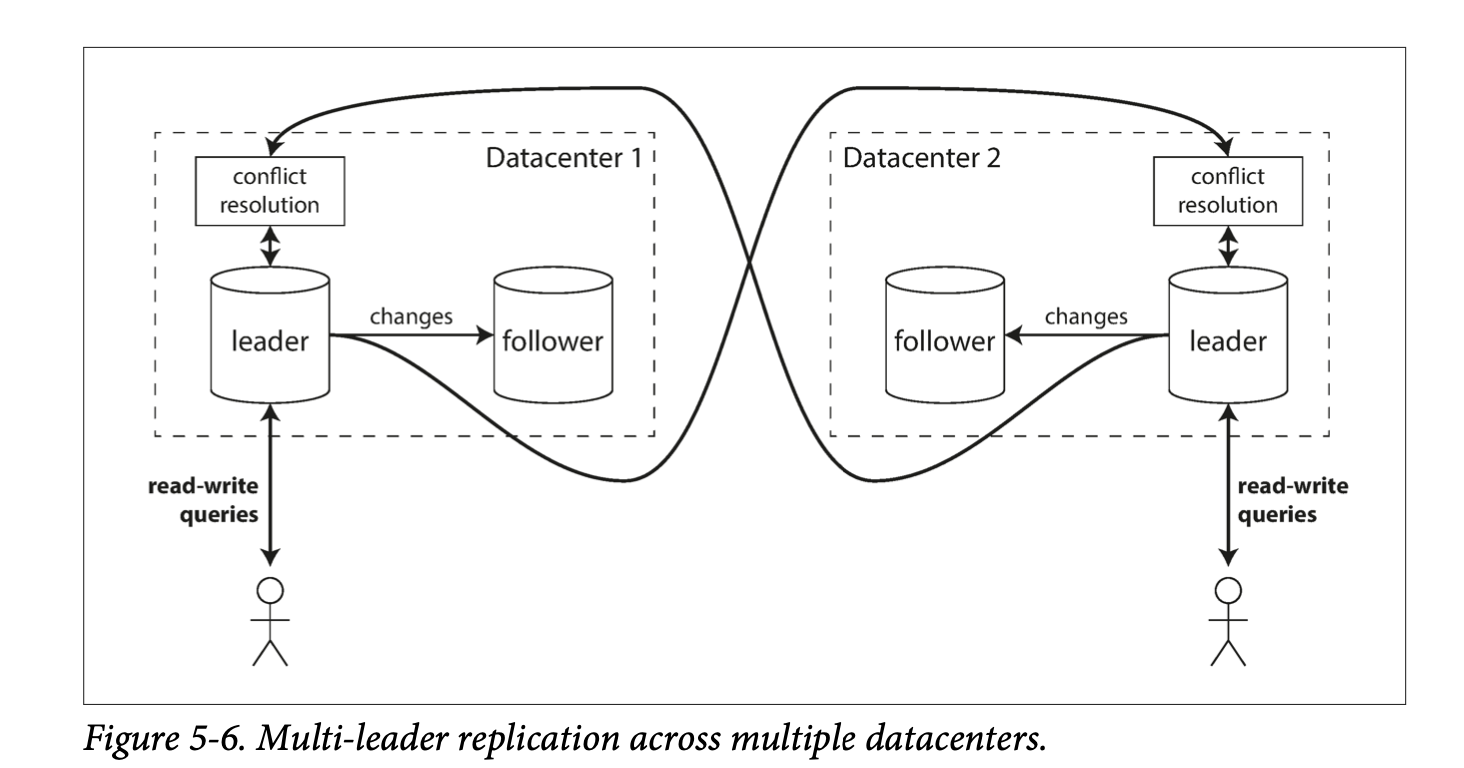

Multi-leader/Master-master/Active-Active replication allows more than one node to accept writes. Each leader accepts writes from a client, and acts as a follower by accepting the writes on other leaders.

Here, each datacenter can have its own leader. This has a better performance for writes, since every write can be processed in its local datacenter (as opposed to being transmitted to a remote datacenter) and replicated asynchronously to other datacenters. It also means that if a datacenter is down, each data center can continue operating independently of the others.

Multi-leader replication has the disadvantage that the same data may be concurrently modified in two different datacenters, and so there needs to be a way to handle conflicts.

Some applications need to work even when offline. Say mobile apps for example, apps like Google Calendar need to accept writes even when the user is not connected to the internet. These writes are then asynchronously replicated to other nodes when the user is connected again. In this setup, each device stores data in its local database. Meaning that each device essentially acts like a leader. CouchDB is designed for this mode of operation apparently.

Real-time collaborative editing applications like Confluence and Google Docs allow several people edit a document at the same time. This is also a database replication problem. Each user that edits a document has their changes saved to a local replica (webbrowser cache), from which it is then replicated asynchronously.

For faster collaboration, the unit of change can be a single keystroke. That is, after a keystroke is saved, it should be replicated.

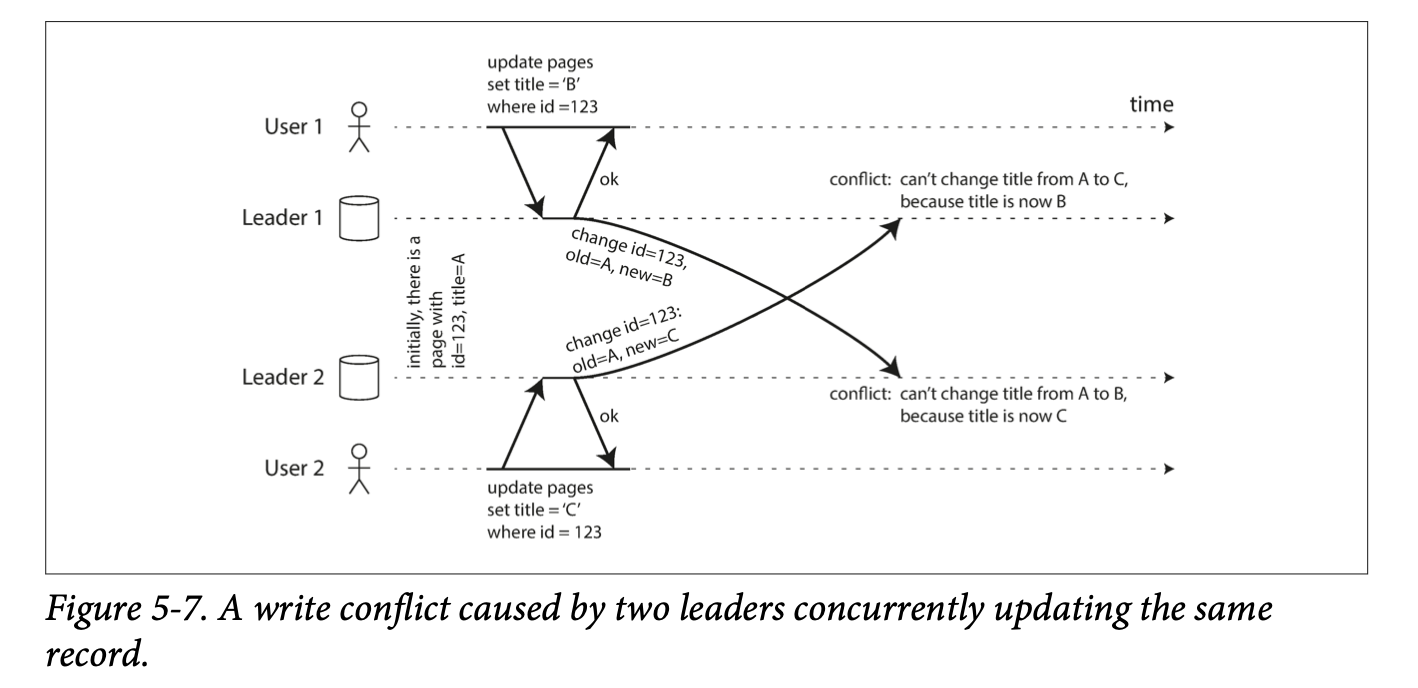

Multi-leader replication has the big disadvantage that write conflicts can occur, which requires conflict resolution.

If two users change the same record, the writes may be successfully applied to their local leader. However, when the writes are asynchronously replicated, a conflict will be detected. This does not happen in a single-leader database.

In theory, we could make conflict detection synchronous, meaning that we wait for the write to be replicated to all replicas before telling the user that the write was successful. Doing this will make one lose the main advantage of multi-leader replication though, which is allowing each replica to accept writes independently. Use single-leader replication if you want synchronous conflict detection.

Conflict avoidance is the simplest strategy for dealing with conflicts. Conflicts can be avoided by ensuring that all the writes for a particular record go through the same leader. For example, you can make all the writes for a user go to the same datacenter, and use the leader there for reading and writing. This of course has a downside that if a datacenter fails, traffic needs to be rerouted to another datacenter, and there's a possibility of concurrent writes on different leaders, which could break down conflict avoidance.

On single-leader, the last write determines the final value of the field. In multi-leader, it's not clear what the final value should be.

The database must resolve the conflict in a convergent way, all replicas must arrive a the same final value when all changes have been replicated. Different ways of achieving convergent conflict resolution.

- Giving each write a unique ID ( e.g. a timestamp, UUID etc.), pick the write with the highest ID as the winner, and throw away the other writes. If timestamp is used, that's Last write wins, it's popular, but also prone to data loss.

- Giving each replica a unique ID, and letting writes from the higher-number replica always take precedence over writes from a lower-number replica. This is also prone to data loss.

- Recording the conflict in an explicit data structure that preserves the information, and writing application code that resolves the conflict at some later time (e.g. by prompting the user).

- Merge the values together e.g. ordering them alphabetically.

The most appropriate conflict resolution method may depend on the application, and thus, multi-leader replication tools often let users write conflict resolution logic using application code. The code may be executed on read or on write:

On write: When the database detects a conflict in the log of replicated changes, it calls the conflict handler. The handler typically runs in a background process and must execute quickly. It has no user interaction. On Read: Conflicting writes are stored. However, when the data is read, the multiple versions of the data are returned to the user, either for the user to resolve them or for automatic resolution. Automatic conflict resolution is a difficult problem, but there are some research ideas being used today:

- Conflict-free replicated datatypes (CRDTs) - Used in Riak 2.0

- Mergeable persistent data structure - Similar to Git. Tracks history explicitly

- Operational transformation: Algorithm behind Google Docs. It's still an open area of research though.

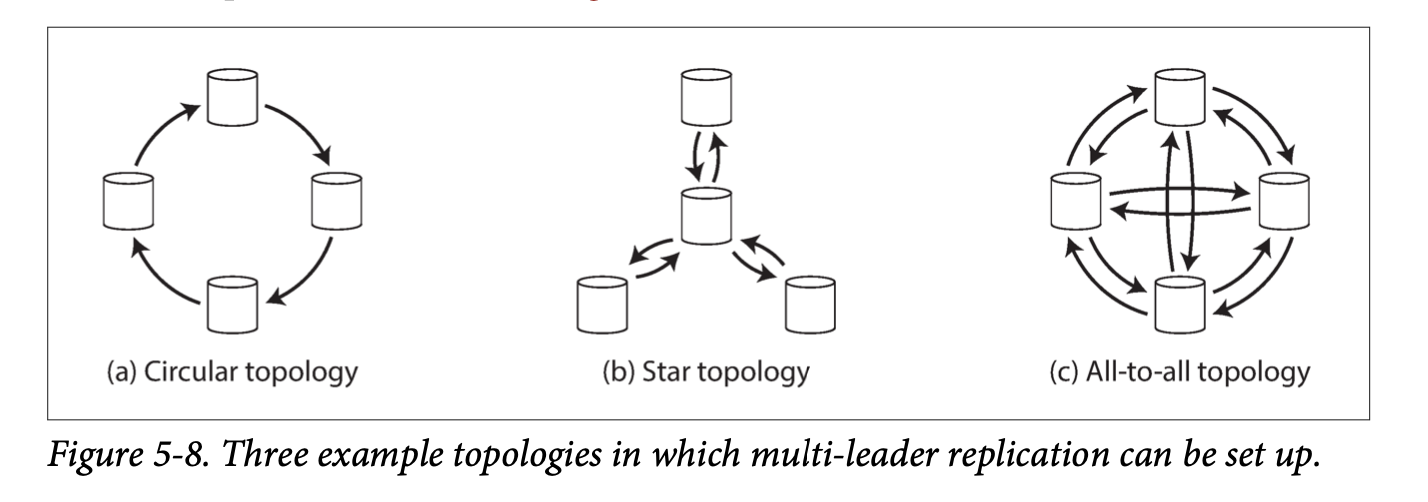

A replication topology is the path through which writes are propagated from one node to another. The most general topology is all-to-all, where each leader sends its writes to every other leader. Other types are circular topology and star topology.

All-to-all topology is more fault tolerant than the circular and star topologies because in those topologies, one node failing can interrupt the flow of replication messages across other nodes, making them unable to communicate until the node is fixed.

In this replication style, the concept of a leader is abandoned, and any replica can typically accept writes from clients directly.

This style is used by Amazon for its in-house Dynamo system. Riak, Cassandra and Voldermort also use this model. These are called Dynamo style systems.

In some leaderless implementations, the client writes directly to several replicas, while in others there's a coordinator node that does this on behalf of the client. Unlike a leader database though, this coordinator does not enforce any ordering of the writes.

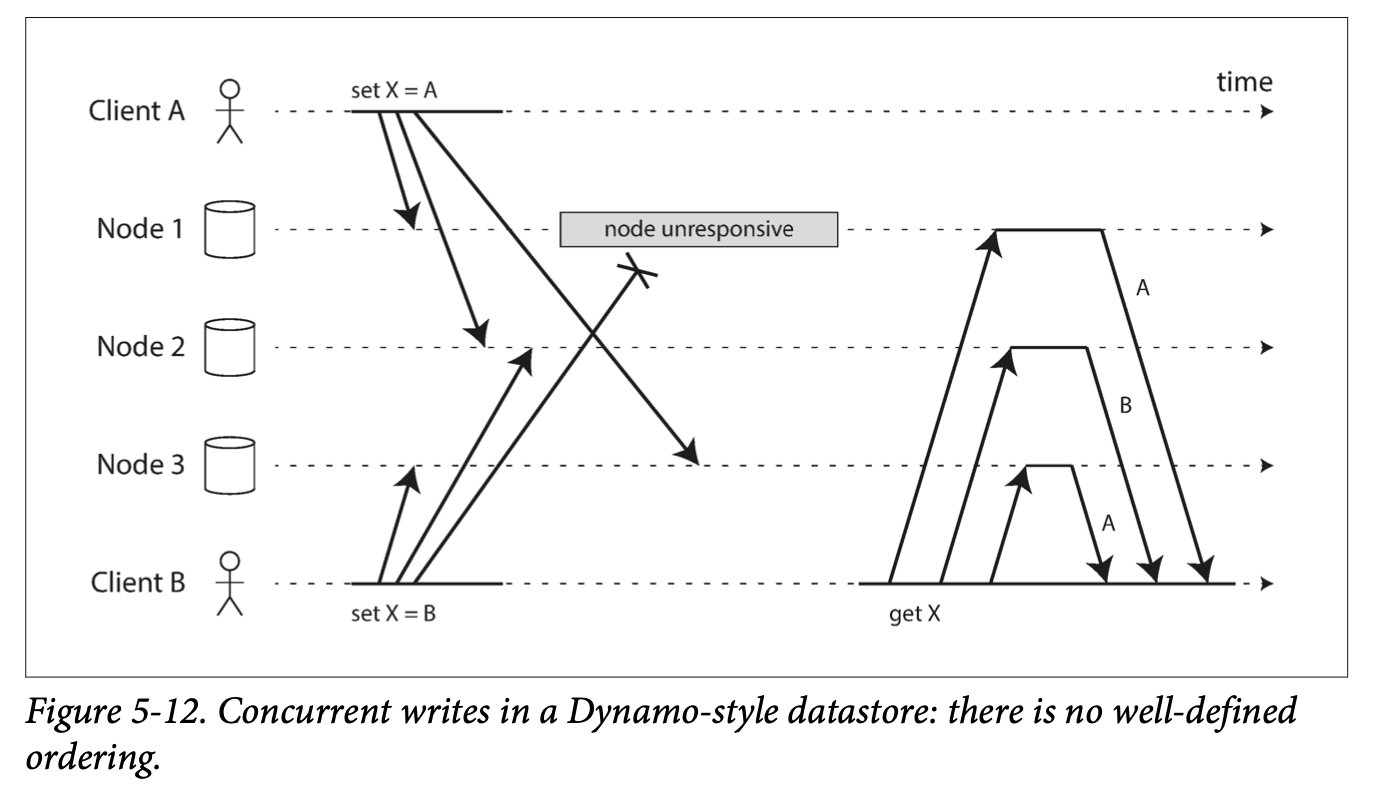

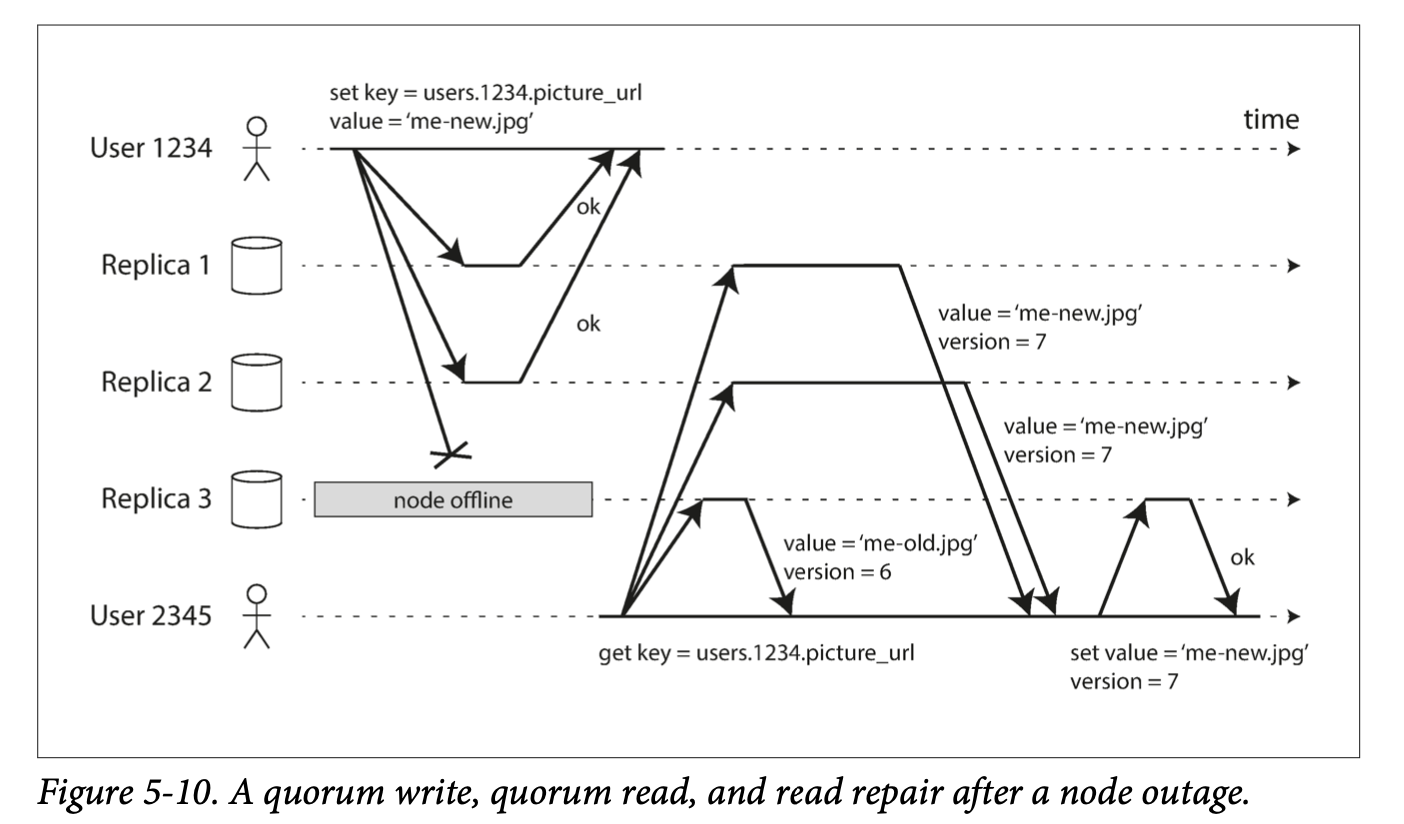

Say there are 3 replicas and one of the replicas goes down. A client could write to the system and have 2 of the replicas successfully acknowledge the write. However, when the offline node gets back up, anyone who reads from it may get stale responses.

To prevent stale reads, as well as writing to multiple replicas, the client also reads from multiple replicas in parallel. Version numbers are attached to the result to determine which value is newer.

When offline nodes come back up, the replication system must ensure that all data is eventually copied to every replica. Two mechanisms used in Dynamo-style datastores are:

Read repair: When data is read from multiple replicas and the system detects that one of the replicas has a lower version number, the data could be copied to it immediately. This works for frequently read values, but has the downside that any data that is not frequently read may be missing from some replicas and thus have reduced durability. Anti-entropy process: In addition to the above, some databases have a background process that looks for differences in data between replicas and copies any missing data from one replica to another. This process does not copy writes in any particular order, and there may be a notable delay before data is copied.

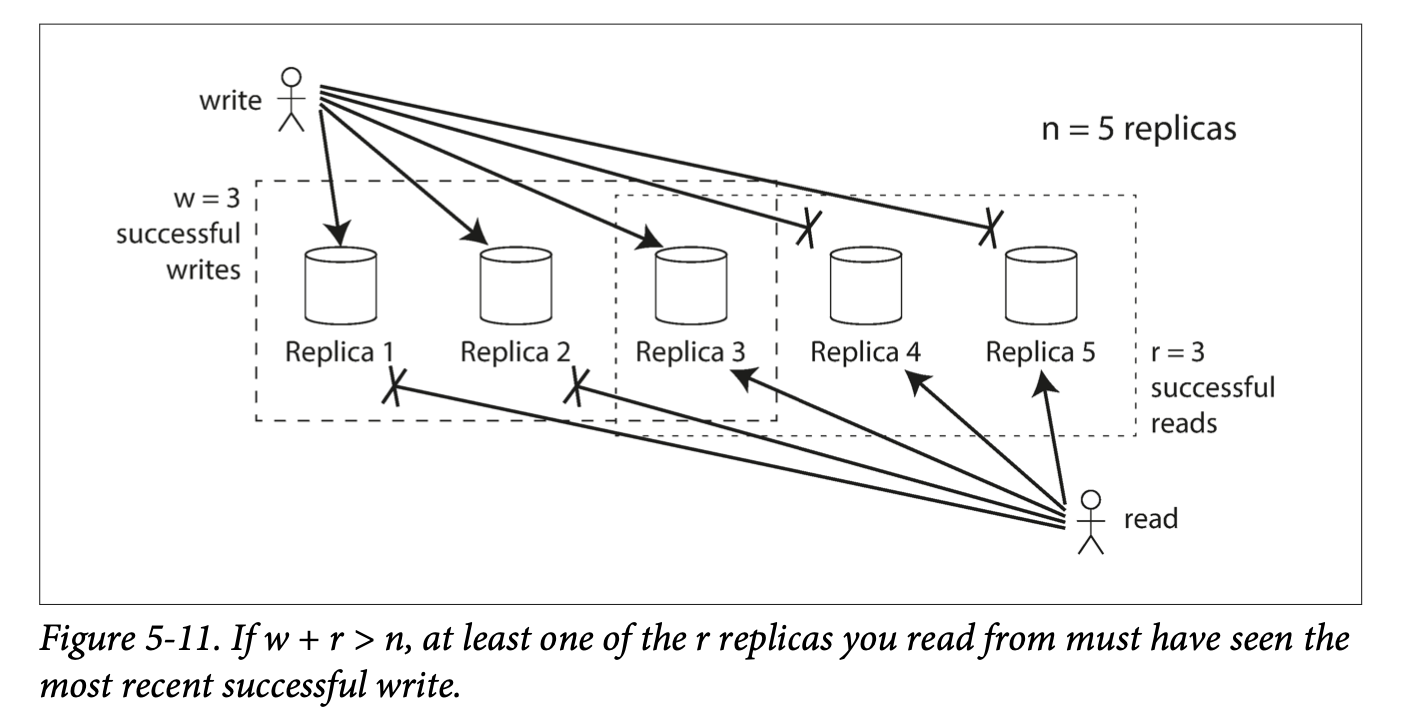

Quorum reads and writes refer to the minimum number of votes for a read or a write to be valid. If there are n replicas, every write must be confirmed by at least w nodes to be considered successful, and every read must be confirmed by at least r nodes to be successful. The general rule that the number chosen for r and w should obey is that:

w + r > n.

This way, we can typically expect an up-to-date value when reading because at least one of the r nodes we're reading from must overlap with the w nodes (barring sloppy quorums which are discussed below)

The parameters n, w, and r are typically configurable. A common choice is to make n an odd number such that w = r = (n + 1)/2. These numbers can be varied though. For a workload with few writes and many reads, it may make sense to set w = n and r = 1. Of course this has the disadvantage of reduced availability for writes if just one node fails.

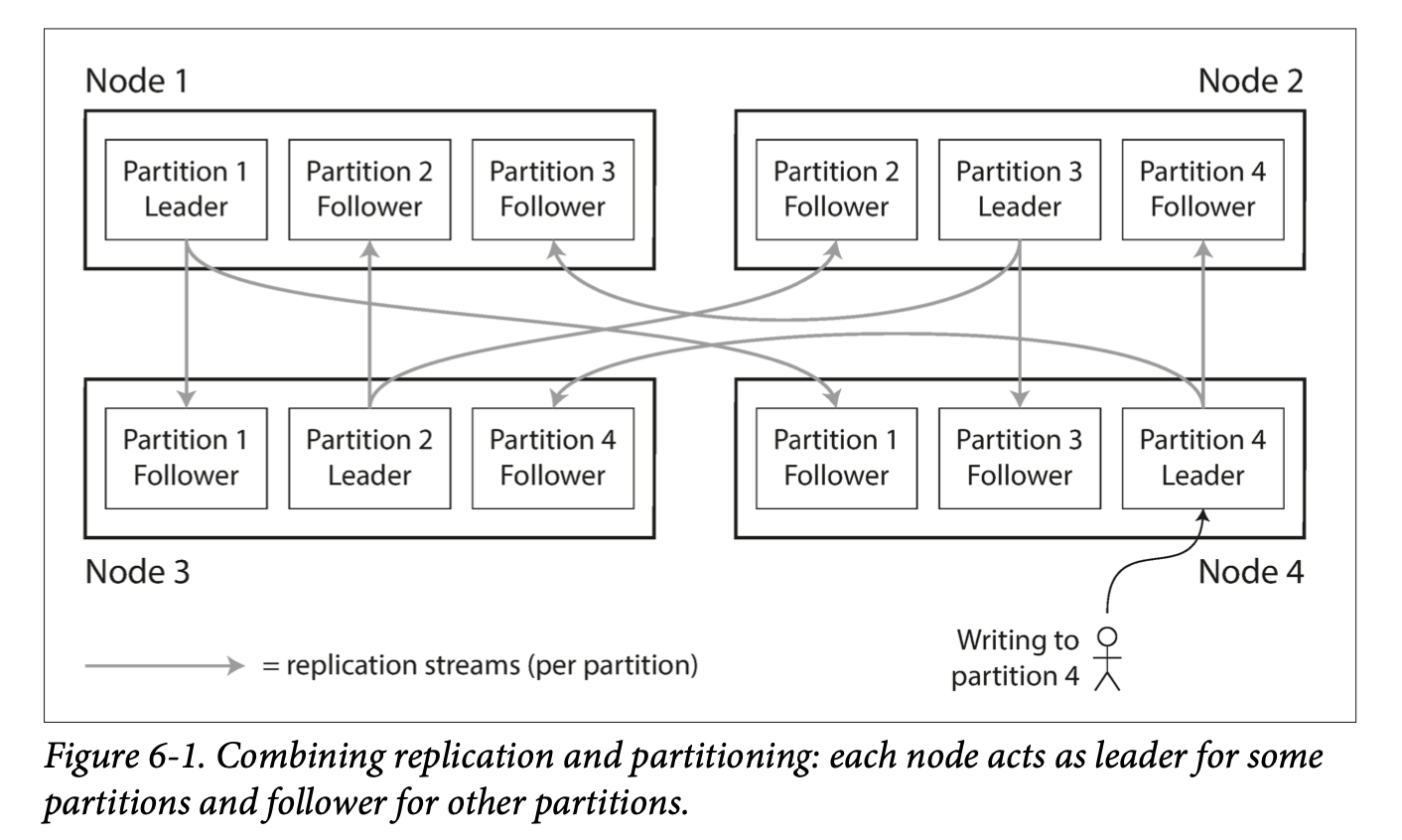

Note that n does not always refer to the number of nodes in the cluster, it may just be the number of nodes that any given value must be stored on. This allows datasets to be partitioned. Partitioning is discussed in Chapter 6.

Note: With w and r being less than n, we can still process writes if a node is unavailable. Reads and writes are always sent to all n replicas in parallel, w and r determine how many nodes we wait for i.e. how many nodes need to report success before we consider the read or write to be successful.

Quorums don't necessarily have to be majorities i.e. w + r > n. What matters is that the sets of nodes used by the read and write operations overlap in at least one node.

We could also set w and r to smaller numbers, so that w + r ≤ n. With this, reads and writes are still sent to n nodes, but a smaller number of successful responses is required for the operation to succeed. However, you are also more likely to read stale values, as it's more likely that a read did not include the node with the latest value. The upside of the approach though is that it allows lower latency and higher availability: if there's a network interruption and many replicas become unreachable, there's a higher chance that reads and writes can still be processed.

Even if we configure our database such that w + r > n , there are still edge cases where stale values may be returned. Possible scenarios are:

- If a sloppy quorum is used, the nodes for reading and writing may not overlap. Sloppy quorums are discussed further down.

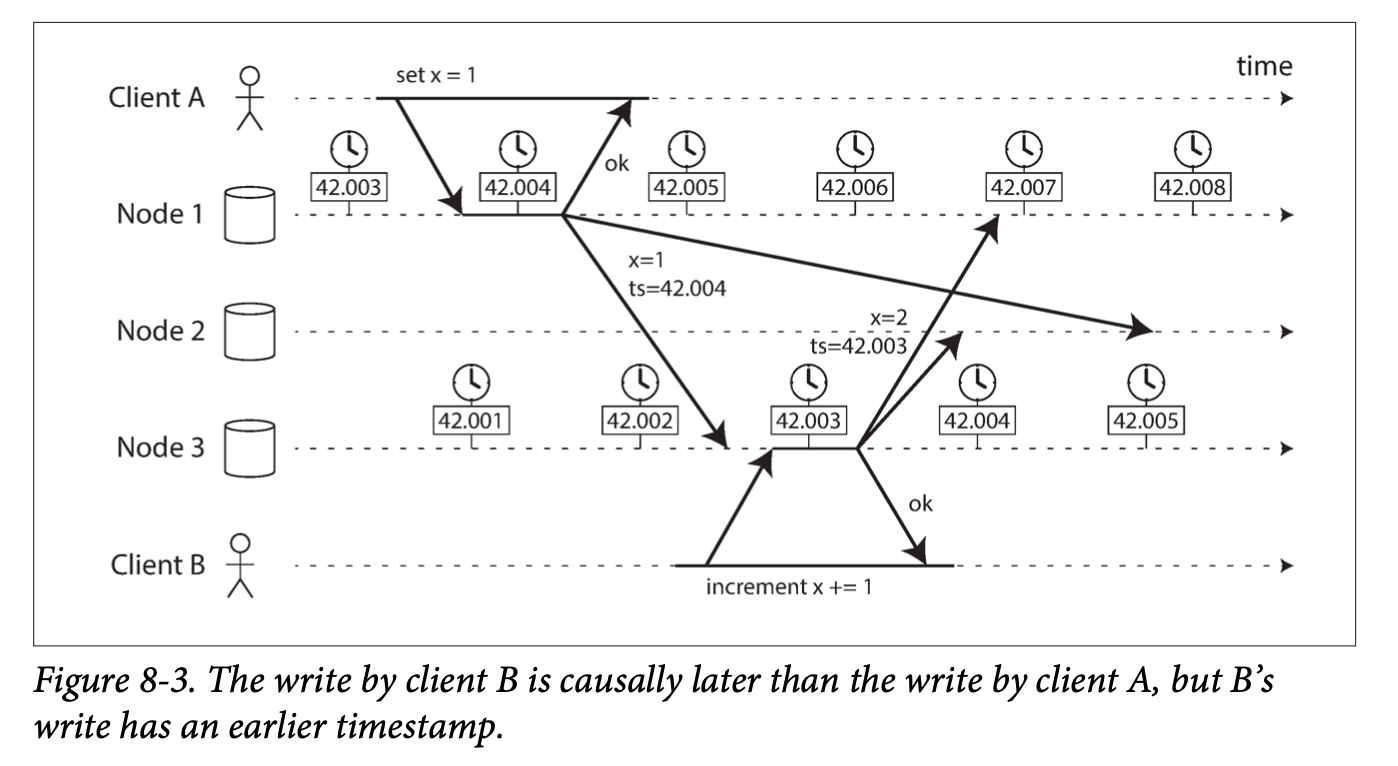

- If two writes occur concurrently, it's still not clear which happened first. Therefore, the database may wrongly return the more stale one. If we pick a winner based on a timestamp (last write wins), writes can be lost due to clock skew.

- If a write happens concurrently with a read, the write may be reflected on only some of the replicas. It's unclear whether the read will return the old or new value.

- In a non-transaction model, if a write succeeds on some replicas but fails on others, it is not rolled back on the replicas where it succeeded. From these points and others not listed, there is no absolute guarantee that quorum reads return the latest written value. These style of databases are optimized for use cases that can tolerate eventual consistency. Stronger guarantees require transactions or consensus.

It's important to monitor whether databases are returning up-to-date results, even if the application can tolerate stale reads. If a replica falls behind significantly, the database should alert you so that you can investigate the cause.

For leader-based replication, databases expose metrics for the replication lag. It's possible to do this because writes are applied to the leader and followers in the same order. We can determine how far behind a follower has fallen from a leader by subtracting it's position from the leader's current position.

This is more difficult in leaderless replication systems as there is no fixed order in which writes are applied. There's some research into this, but it's not common practice yet.

Databases with leaderless replication are appealing for use cases where high availability and low latency is required, as well as the ability to tolerate occasional stale reads. This is because they can tolerate failure of individual nodes without needing to failover since they're not relying on one node. They can also tolerate individual nodes going slow, as long as w or r nodes have responded.

Note that the quorums described so far are not as fault tolerant as they can be. If any of the designated n nodes is unavailable for whatever reason, it's less likely that you'll be able to have w or r nodes reachable, making the system unavailable. Nodes being unavailable can be caused by anything, even something as simple as a network interruption.

To make the system more fault tolerant, instead of returning errors to all requests for which can't reach a quorum of w or r nodes, the system could accept reads and writes on nodes that are reachable, even if they are not among the designated n nodes on which the value usually lives. This concept is known as a sloppy quorum.

With a sloppy quorum, during network interruptions, reads and writes still require r and w successful responses, but they do not have to be among the designated n "home" nodes for a value. These are like temporary homes for the value.

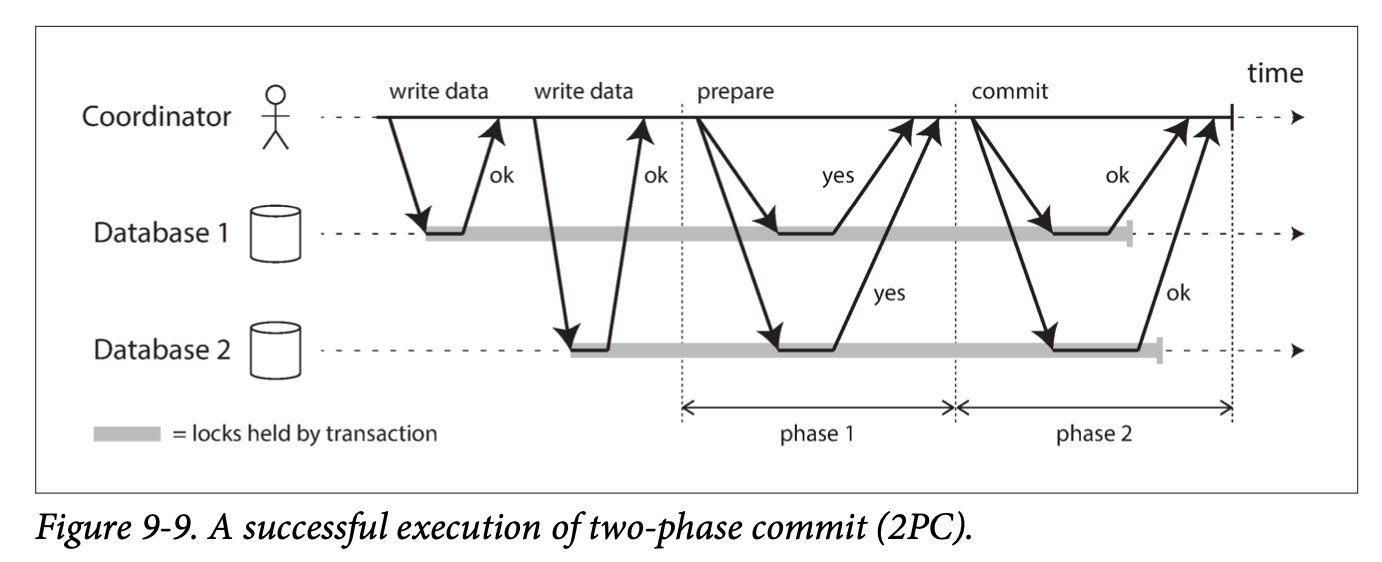

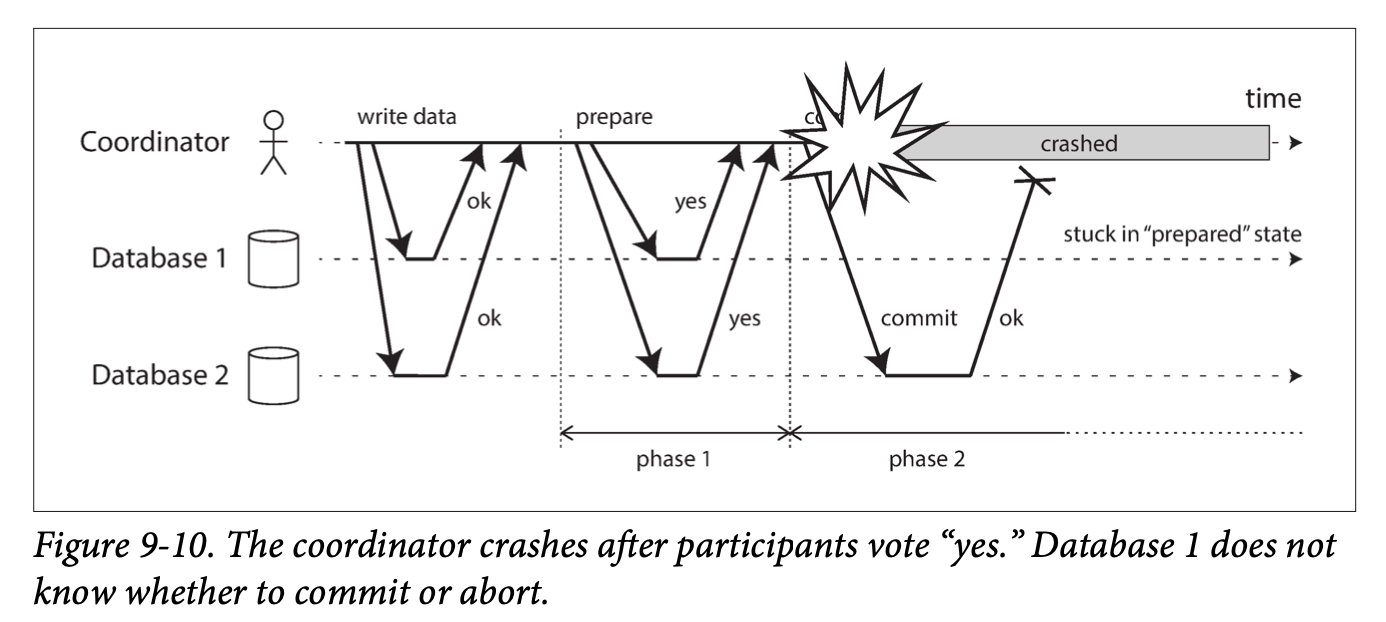

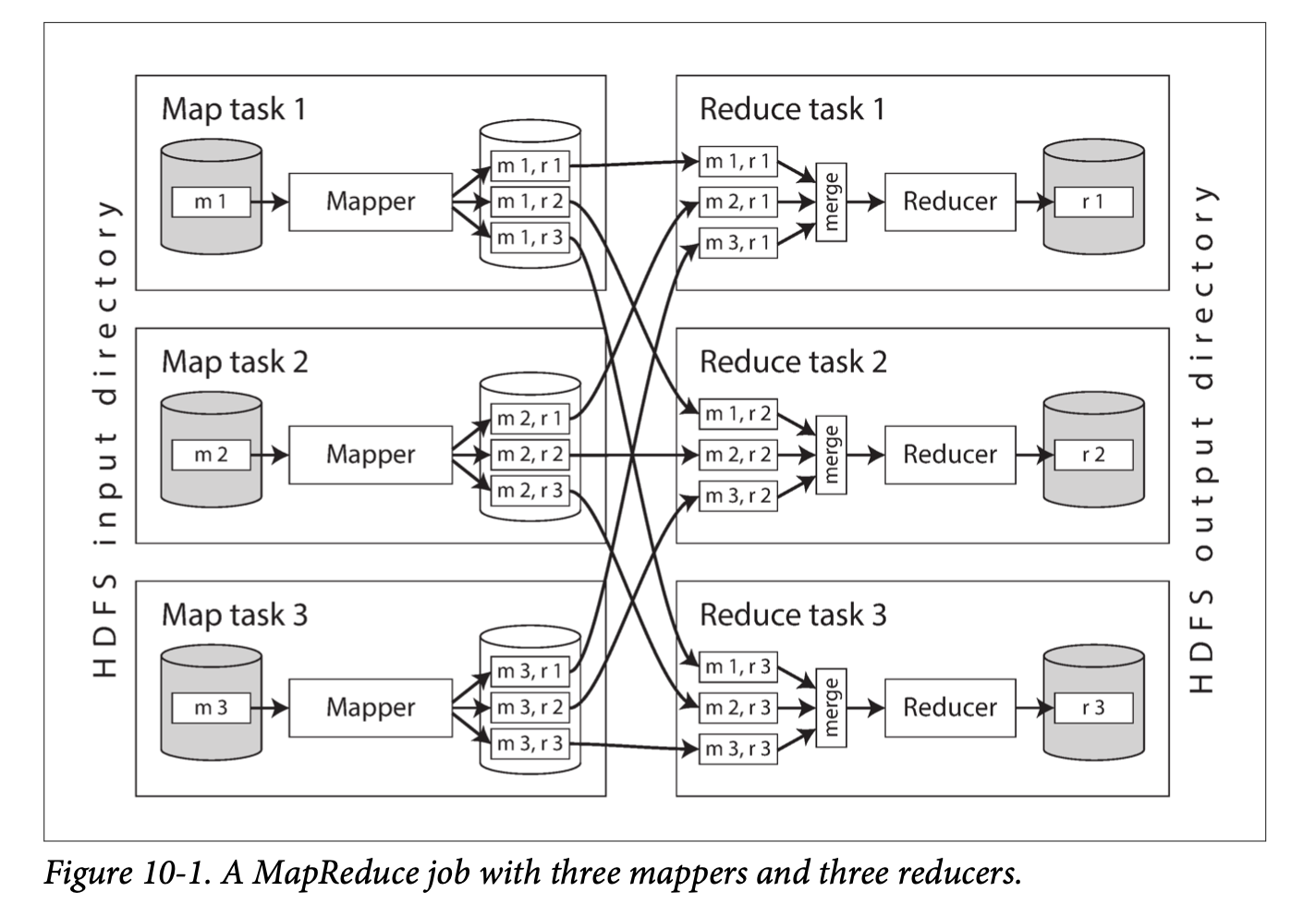

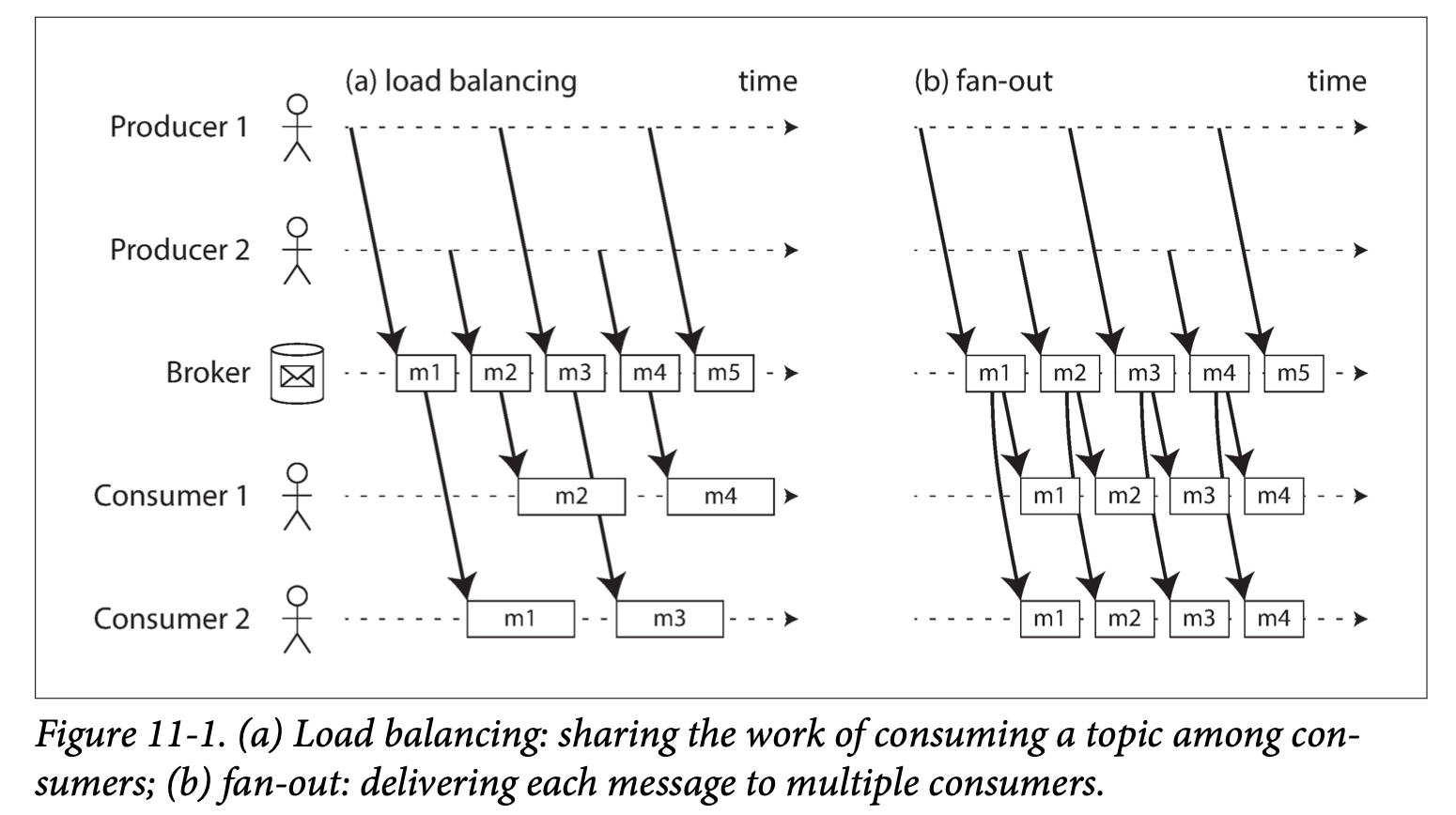

When the network interruption is fixed, the writes that were temporarily accepted on behalf of another node are sent to the appropriate "home" node. This is hinted handoff.