This is the new and integrated scene manipulation service, that also offers a lookup service.

- Make sure you have ROS2 and Rust installed.

- Make sure you have libclang installed. (e.g. libclang-dev on ubuntu)

- You need to source your ROS2 installation before building/running.

cd other_ws/src/

git pull https://github.com/sequenceplanner/scene_manipulation_service.git

cd ..

colcon build --cmake-args -DCARGO_CLEAN=ON

ros2 launch scene_manipulation_bringup sms_example.launch.py

A critical ROS tool that enables preparation, commissioning and control of intelligent automation systems is tf. In short, tf is a ROS package that lets the user keep track of multiple coordinate frames over time. It does so by maintaining relationships between coordinate frames in a tree structure buffered in time, and lets the user manipulate transforms between any two coordinate frames at any desired point in time. Usually, a global tf tree keeps track of all things in a system, however, in some cases it can be beneficial to have multiple trees to keep track of frames in certain subsystems.

In a nutshell, tf is a topic where information about coordinate frames of a system are published on. This is done with transforms, where each transform contains information about one relationship between two coordinate frames. This information is maintained as a tree structure, as all transforms define strict parent-child relationships between such frames. We like to look at tf as having two ways of getting information to its tree and maintaining coordinate frames:

- Static transform broadcasters

- Active transform broadcasters

Static transform broadcasters publish transforms that are static in time, i.e. the transformation between the frame and its parent is not expected to change over time. Because of this, the time dimension can be disregarded and the transforms can be published very sparsely. Examples of static transforms could be bolt holes defined in the engine frame, or a sensor defined in the camera’s mounting point. These transformations define where such frames are, relative to their parent frame, and they are not expected to ever change.

Active transform broadcasters publish transforms that are active in time, i.e. the transformation between the frame and its parent is expected to change over time. We now

have to publish the transform together with a timestamp, so that tf can keep track of changing transformations in time and provide us with the correct answer when we look

up the tf tree at a certain time point. Examples of active transforms range across mobile robot bases defined in a world coordinate frame, products that are transported on a conveyor belt, and multiple DoF manipulator links defined in their parents links via joints.

For preparation, commissioning and control of intelligent automation systems, we use the notion of scenarios. A scenario is represented by its resources, their arrangement and the task that they are going to execute. Preparing such scenarios is one of the first steps of realizing an intelligent automation system. In order to do that efficiently, we utilize tf to define and prepare scenarios, keep track of where things are in the world, and calculate relationships between those things.

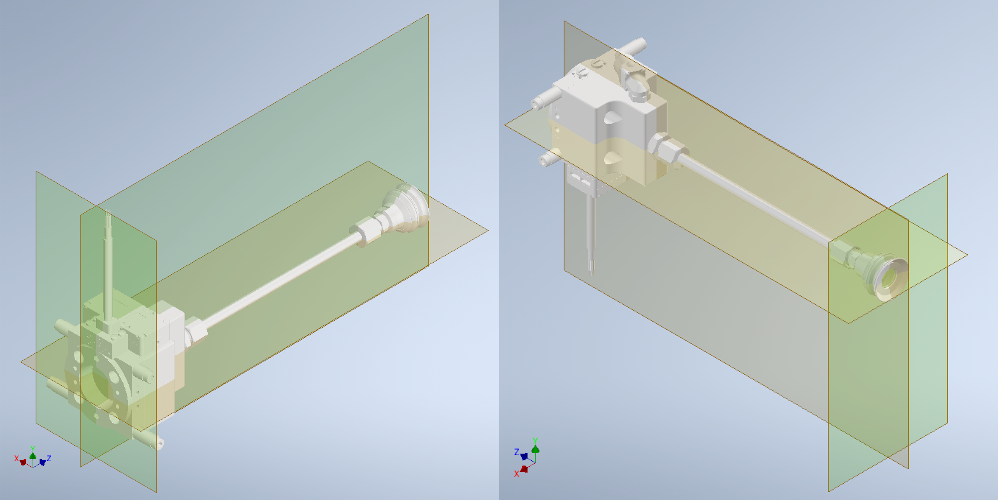

Let’s look at a pick and place and how we would prepare a scenario for picking some items. We can start with supplied original CAD files of components, and modify their coordinate frames having in mind how they should couple or interact with other components of the system. For example, a tool for picking certain items should have a tool center point frame at a correct place, as well as a main coupling frame. The left side of the figure below shows how the main frame of a suction tool was set, in order to properly couple with the robots rsp connector.

The right side of the figure above shows how the tool center point was set in order to match the frames of items to be picked up with this tool. Such frames have unique names in order for tf to be able to keep track of them. Let’s call the main frame svt, short for small vacuum tool, and the tool center point frame svt_tcp. The svt_tcp is defined in the main svt frame as a static transform since it is not expected for the transformation between them to change. On the other hand, the main svt frame is expected to be picked up by the robot or left at the tool stand, so let’s define the svt frame as an active transform with an initial parent at the tool stand. As the tool is expected to have a home position when released by the robot, let’s call this frame svt_home.

To define these relationships, our current scenario has a collection of frame description files in a .json format. Let’s look at the descriptions of these two frames:

svt.json: svt_tcp.json:

{ {

"active": true, "active": false,

"child_frame_id": "svt", "child_frame_id": "svt_tcp",

"parent_frame_id": "svt_home", "parent_frame_id": "svt",

"transform": { "transform": {

"translation": { "translation": {

"x": 0.0, "x": 0.0,

"y": 0.0, "y": 0.0,

"z": 0.0 "z": 0.313365

}, },

"rotation": { "rotation": {

"x": 0.0, "x": 1.0,

"y": 0.0, "y": 0.0,

"z": 0.0, "z": 0.0,

"w": 1.0 "w": 0.0

} }

} }

} }

The measurements in these description files are taken directly from Inventor when preparing the tool frames. As such, if the CAD file exactly matches the real tool, we can be quite confident that the tf tree will be an accurate representation of the real world. As we have prepared the tool frames, we can use the same technique to prepare everything else in the scenario, including the items that have to be picked by the robot.

Keeping track of where things are in a reliable and continuous way is of utmost importance for realizing truly flexible automation systems. This is where we rely on tf and the scene manipulation service.

As previously mentioned, the ROS package tf plays a crucial role in the way we develop and control intelligent automation systems. In a tf instance of a running scenario, all the frames of a system that are either directly tracked or estimated, are maintained in a tree structure. In general, each node can have several children and exactly one parent, except for the root or leaf nodes which don’t have any parents or children, respectively.

Usually, such a tree structure has a defined topology where frames can change the active transformation relationships, but not their parent-child relationships. This is a safety feature as defining additional parents for a node and generating loops in the tree is forbidden. However, when executed correctly and the tree structure is maintained, forcing changes in parent-child relationships can unlock additional

features. We call this scene manipulation service.

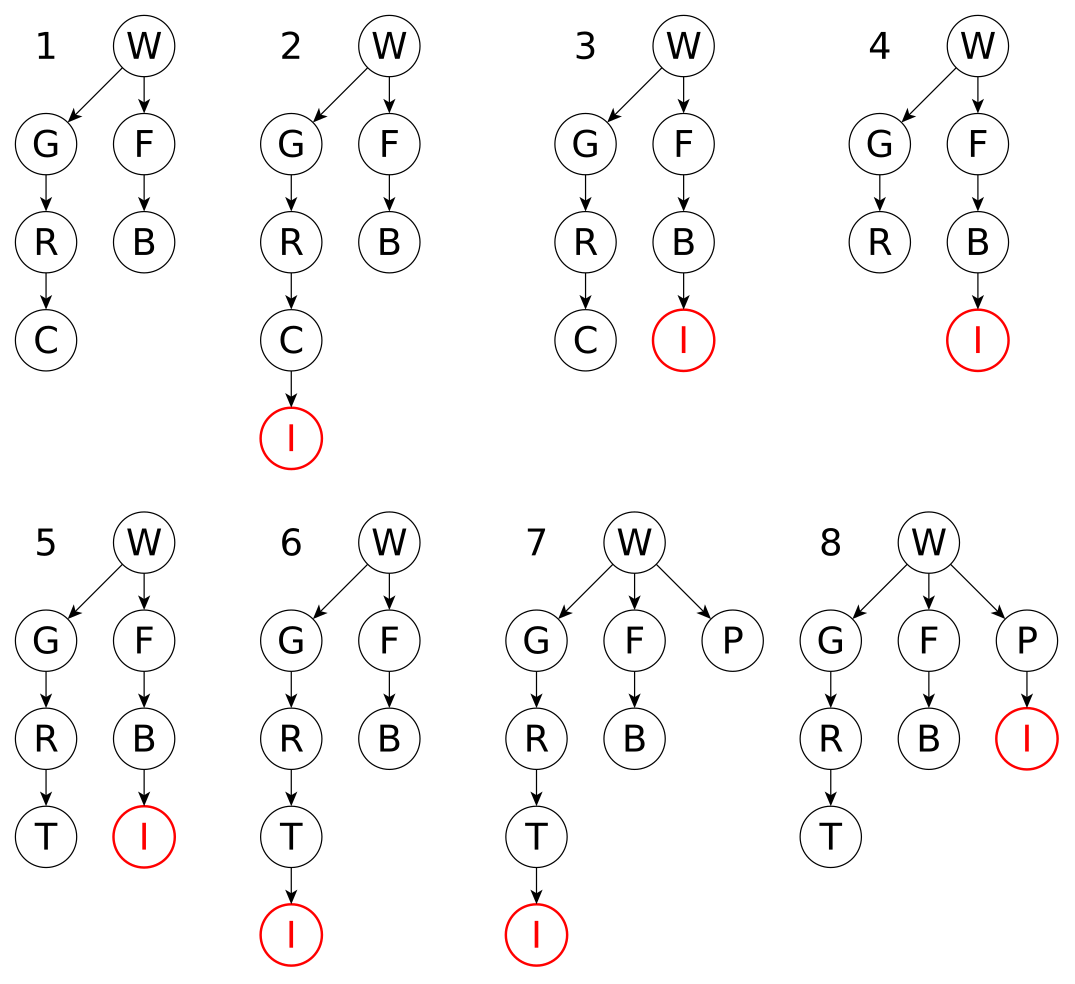

Let’s look at an example about how we keep track of an item that is scanned, picked, and then put on a moving platform. Shown on the figure below is an example tf tree that is being manipulated in order to estimate where the actual item is in the real world. Starting from the top left of the figure, we have a simple tf tree with the following nodes: W - world, G - gantry, F - facade, R - robot, B - bin, and C - camera.

After detecting an item, it is put into the tf tree as a child node of the camera frame, as shown with I - item, in step 2 of the figure above. As the robot has to move in order to leave the camera and attach the tool, we re-parent the item frame

to the bin frame, as seen at step 3. Steps 4 and 5 show the leaving of the camera and attaching the tool, shown with T- tool. At step 6, the tool detects that it is picking an item, and at that point the parent of the item frame is changed to that tool. The moving platform appears in the scene and added into the world frame as P - platform. At step 8, the tool leaves the item on the platform.

The scene manipulation service has three main features:

- Broadcasting frames

- A lookup service

- A manipulation service

In order to enable all of these three feature in one node, we maintain our own local buffer. Since we are not doing any path planning, i.e. we don't need any frame interpolation in time to generate trajectories, the buffer that is maintained here is simpler than the buffer that one would use for motion planning. Contrary to keeping all incomming frames in the buffer for DEFAULT_BUFFER_TIMESPAN which is 10 seconds, the buffer is a simple hashmap which overwrites the previous value if a fresher one comes in.

Nevertheless, the frames should expire if not published with an adequate frequency, so we limit the ammount of time we keep the active frames in our buffer for ACTIVE_FRAME_LIFETIME and the static frames for STATIC_FRAME_LIFETIME. The buffer is maintained at a refresh rate of BUFFER_MAINTAIN_RATE.

Frames are broadcasted from two places: loaded from a folder using .json descriptions, or received from clients using the scene manipulation service. Both are kept in one hashmap named broadcasted_frames so that duplicates are avoided. If frames are added, changed or removed from the folder manually, that will be reflected in the tf world as well (as long as such frames are defined as active).

The path of this folder, i.e. where the scenario is loaded from, should be specified when launching the scene manipulation service with the scenario_path parameter. There are two options here for convenience. If one wishes not to manipulate the frames manually by adding, changing or removing .json files, the more convenient option is to install the scenario directiory when building the package and using FindPackageShare to locate the scenario folder. Otherwise, it is more convenient to specify the absolute path to such a scenario folder. Look at the sms_example.launch.py in the scene_manipulation_bringup package for examples.

The scene manipulation service node can also be launched without a provided scenario_path parameter. Then the load_scenario service can be used to forward such a path and point to a folder during runtime, using the LoadScenario service message. This can also be used to re-load or change the scenario during runtime, though cases where that is needed are rare.

As the scene manipulation service node maintains its own buffer, it is easy to lookup relationships between frames stored in that buffer. This is offered with the lookup_transform service using the LookupTransform service message. Asking for all transforms currently maintained in the local buffer is possible through the get_all_transforms service using the GetAllTransforms service message.

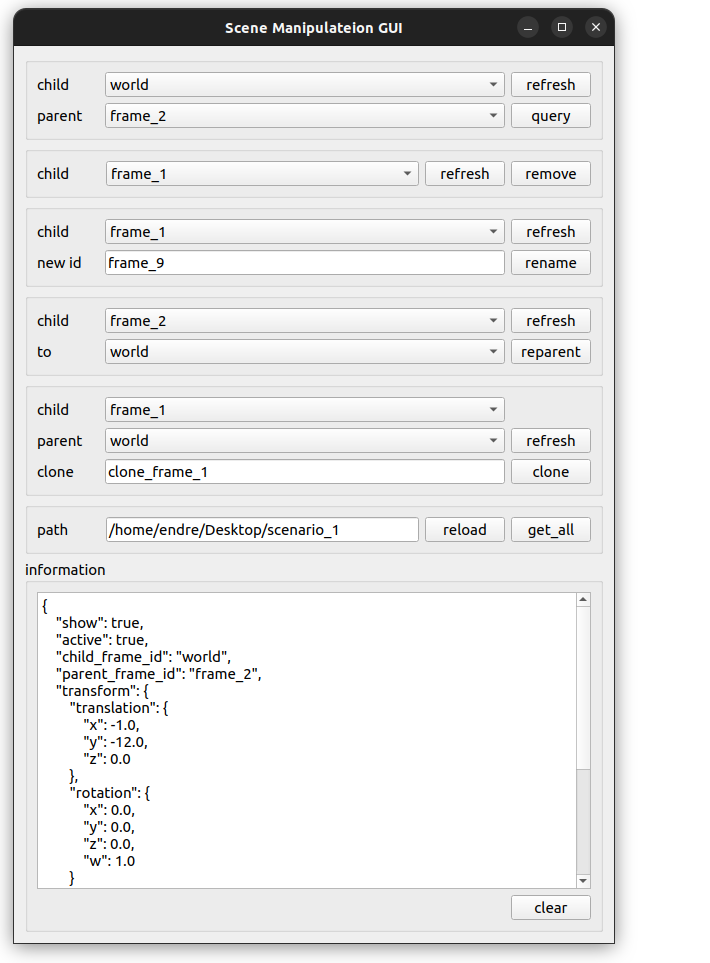

The scene manipulation service allows adding, removing, renaming, moving, reparenting and cloning frames in a scenario. It is done throught the manipulate_scene service using the ManipulateScene service message. Here is what the following commands do:

add- If a frame is not published by smss broadcaster nor does it exist in its buffer, it can be added using theaddcommand. With this command, the full transform should be provided in the message, and the frame will then be put in the providedparent_frame_id.remove- Enables removing a frame from the broadcaster. If the frame is published elsewhere, it can not be removed.CAUTION:child frames of the removed frame will be orphaned.rename- Enables renaming a frame from the broadcaster, with the provided new namenew_frame_id. If the frame is published elsewhere, it can not be renamed.CAUTION:child frames of the renamed frame could be orphaned if they don't know that their parent was renamed.move- Enables moving a frame using the specified transform from the message. In this case, the parent will remain the same so theparent_frame_idis not considered.reparent- Enables changing the parent of a frame to another parent. In this case, only theparent_frame_idis considered as the position of the frame will remain the same in the world.clone- Enables dupliacting thechild_frame_idframe and naming it withnew_frame_id. The frame will remain in the same position, but the parent of the clone can be specified withparent_frame_id.

Flowcharts that depict how the manipulation is performed and what can happen can be found in the description.

The scene manipulation GUI can be launched with:

ros2 launch scene_manipulation_bringup sms_example_with_gui.launch.py

ros2 run rviz2 rviz2

Christian Larsen (sms concept) - Fraunhofer Chalmers Centre

Martin Dahl (r2r) - Chalmers University of Technology

Kristofer Bengtsson (supervision) - Volvo AB