Implementation for the lesson Compiling Engineering (2020 Spring) in Peking University.

Adapted from UCLA CS 132 Project.

Table of Contents:

- MiniJava-Compiler

- spim: a self-contained simulator that runs MIPS32 programs

- Java JDK with version >= 11

apt install -y spim default-jre default-jdkThat's easy! Just type these in your terminal:

./configure

make && make buildType make test to run all tests. Type make test -j<number of threads> for multithreading.

The works are divided into five parts, each of which is a homework of the course:

- Semantics analysis: type check a MiniJava program

- IR generation (1): compile a MiniJava program to Piglet

- IR generation (2): compile a Piglet program to Spiglet

- Register allocation: compile a Spiglet program to Kanga

- Native code generation: compile a Kanga program to MIPS

Below are the tools used in this project. The jar files are under the /deps folder.

JavaCC is an open-source parser generator and lexical analyzer generator written in the Java. It allows the use of more general grammars, although left-recursion is disallowed.

In fact, other tools like Lex can do the same work. But JavaCC works better with Java applications.

JTB is a syntax tree builder to be used with JavaCC. It proviodes a more convenient way to write lexical specification and the grammar specification.

What is more, JTB will generate a set of syntax tree classes based on the productions in the grammar. This is the killer feature of JTB. The classes utilize the Visitor design pattern and allows us to traverse the abstrct syntax tree with ease. The code below scans the code to find out all the class names in a MiniJava program. It only takes a few lines because the generated Vistor classes do most of the dirty work behind the scene.

class ScanForClassName<T extends ClassCollection> extends GJVoidDepthFirst<T> {

public void visit(final ClassDeclaration node, final T classes) {

// the class name

classes.add(node.f1.f0.tokenImage);

}

public void visit(final ClassExtendsDeclaration node, final T classes) {

// the class name

classes.add(node.f1.f0.tokenImage);

}

public void visit(final MainClass node, final T classes) {

classes.add(node.f1.f0.tokenImage);

}

}The Piglet interpreter.

The Spiglet checker. It only checks whether a program is written in Spiglet. To evaluate a Spiglet program, use the Piglet interpreter PGI, because Spiglet is the subset of Piglet.

The Kanga interpreter.

SPIM is a self-contained simulator that runs MIPS32 programs. It runs on Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux and provides simple debugger and minimal set of operating system services. In this project, we need to ask the operating system to print the result.

Note that SPIM does not execute binary (compiled) programs.

Because Java is a typed language, we should implement type checking for its subset (i.e., MiniJava).

For simplicity, we say that "type A matches with type B" if any one of the following conditions holds:

- A and B are the same type

- B is the superclass of A

Note that "A matches with B" does not imply "B matches with A".

The type checker should examinate each of the following type constrains:

- The type of a returned expression should match with the type of the method whose body contains the expression.

- The type of the right side of an assignment should match with the type of the left side.

- The type of the condition expression of a "if" statement or a "while" statement should be boolean.

- The types of comparison operants should be integer.

- A method should be invoked with a class type to which the method belongs.

- The type of method operants should match with the signature of that method.

The checker does the type checking in four passes:

- Collect all the class names.

- Infer the inheritance relations.

- Collect all the methods and their signatures.

- Traverse the AST to compute the type of each expression. In the same pass, the checker also check every type constrain.

Although MiniJava is a subset of Java, some programs that pass our typecheck can not pass the Java compiler because of the error "variable might not have been initialized". This is because Java has the rule to initialize the local variable before accessing or using them and this is checked at compile time, but our Minijava does not take such constrain into account. In this project, we choose to ignore that error. In fact, to detect uninitialized variable, we have to do the control-flow analysis (CFA), which is the major work of Part 4.

Our type structure is illustrated below.

- class Type

- class PrimitiveType

- class BoolType

- class IntType

- class ArrType

- class VoidType

- class ClassType

- class PrimitiveType

- class Method

- class StaticMethod

To check whether "type A matches with type B", we use the typeCastCheck function.

class Type {

static void typeCastCheck(final Type from, final Type to) {

if (from instanceof PrimitiveType) {

if (!from.getClass().equals(to.getClass())) {

Info.panic("incompatible primitive type " + from + " -> " + to);

}

} else if (to instanceof PrimitiveType) {

Info.panic("cast ClassType to PrimitiveType " + from + " -> " + to);

} else {

ClassType a = (ClassType) from;

final ClassType b = (ClassType) to;

while (a != null) {

if (a.name.equals(b.name)) {

return;

}

a = a.superclass;

}

Info.panic("cast to derived class failed " + from + " -> " + to);

}

}

}There are some corner cases that should be identified as Type Error when doing the semantics analysis. We are going to list them here.

- Circular inheritance. With simple graph theory, we can check whether a loop in the directed inheritance graph using Depth First Search tree within

$O(n)$ time, where the$n$ is the number of classes. - The overriding method has a different return type.

- A temporary variable declared in a method body has the same name with one of the method argument names.

In the first part of the IR generation, we are going to translate Minijava into Piglet that is an IR with structured scoping, or tree-based instruction (while we will sonn see Spiglet is an IR without structured scoping).

The most interesting part is the memory layout. We now discuss the integer arrays and objects.

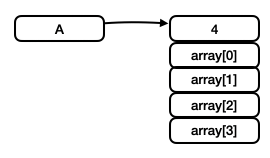

The memory representation of the code snippet below are shown in the figure. The variable is fundamentaly a pointer to a table. The first element of the table is the length of the array (in our example, the length is 4) and the others elements are the content of the array.

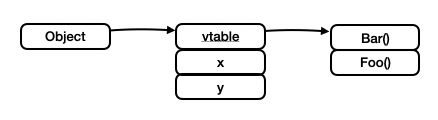

int[] A = new int[4];An instance of a class is also a pointer to a table. The first element of the table is another pointer to a vitrual table which is used for dynamically dispatch. The rest elements of the table are the field members of the instance.

class Base {

int x, y;

int Bar() { ... }

int Foo() { ... }

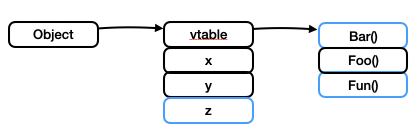

}When inherited from a base class, a class simply adds new field members to the table and modifies the vitural table conforming to the overriding rule. In the figure below, the differences between the drived class and the base class are highlighted in blue.

class Derived extends Base {

int z;

int Bar() { ... }

int Fun() { ... }

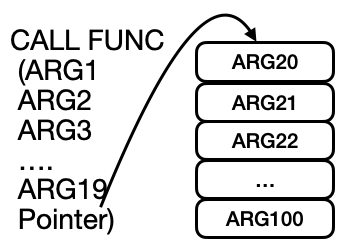

}When the number of arguments excceded 20, we have to find another way to pass the arguments because the Piglet interpreter support at most 20 arguments. Here is our solution. The first nineteen arguments are passed as usual, whereas others are stored in a new table. A pointer to the table is passed as the twentieth argument, as illustated in the figure.

In addition, we have to fill the uninitialized memory cells as zeros explicitily because the Piglet interpret forbid reading a memory cell until it is written to. To achieve this, we hard-code a memset function that will be appended to the generated result,

/* memset(start, length) */

__memset [2]

BEGIN

/* i = 0 */

MOVE TEMP 100 0

__memset_L2 NOOP

/* i < length */

CJUMP LT TEMP 100 TEMP 1 __memset_L1

HSTORE TEMP 0 0 0

MOVE TEMP 0 PLUS TEMP 0 4

MOVE TEMP 100 PLUS TEMP 100 1

JUMP __memset_L2

__memset_L1 NOOP

RETURN 0 END

and use this function to make zero-filled memory cells.

/**

* new a()

*

* BEGIN MOVE TEMP 1 HALLOCATE $(size of a) MOVE TEMP 2 HALLOCATE $(size of

* vitrual table) HSTORE TEMP 1 0 TEMP 2 HSTORE TEMP 2 0 $(method1) HSTORE TEMP

* 2 4 $(method2) HSTORE TEMP 2 8 $(method3) ... RETURN TEMP 1 END

*/

public Type visit(final AllocationExpression n) {

final String name = n.f1.f0.tokenImage;

final ClassType type = classes.get(name);

final String temp1 = e.newTemp();

final String temp2 = e.newTemp();

e.emitOpen("/*new", name, "*/", "BEGIN");

// plus one for virtual table

final int field_size = type.sizeOfClass() + 1;

e.emit("MOVE", temp1, "HALLOCATE", e.numToOffset(field_size));

e.emit("MOVE", temp2, "CALL", "__memset", "(", temp1, Integer.toString(field_size), ")");

e.emit("MOVE", temp2, "HALLOCATE", e.numToOffset(type.sizeOfTable()));

e.emit("HSTORE", temp1, "0", temp2);

for (final ClassType.Method method : type.dynamicMethods) {

e.emit("HSTORE", temp2,

e.numToOffset(type.indexOfMethod(method.name)), method.getLabel());

}

e.emitClose("RETURN", temp1, "END");

return type;

}Beacuse Minijava and Piglet have similar structrue, we couple the IR generation design with semantic analysis for the coding convenience and readability. The code snippet below demonstrates our design.

/**

* a.length

*

* BEGIN HLOAD TEMP 1 a 0 RETURN TEMP 1 END

**/

public Type visit(final ArrayLength n) {

final String temp1 = e.newTemp();

e.emitOpen("/* .length */", "HLOAD", temp1);

final Type a = n.f0.accept(this);

e.emitBuf("0");

e.emitClose("RETURN", temp1, "END");

if (a instanceof ArrType) {

return new IntType();

} else {

Info.panic("ArrayLookup");

return null;

}

}As we see, this method accomplishes two core tasks. First, we type check the variable that .length is applied to is of type int[]. Second, we generation the Piglet code to fetch the length field of the array.

Our implementation output detailed comment on the Piglet code. This yields better readability and is much easier to debug. Below is a sample output.

MAIN

PRINT

CALL BEGIN

MOVE TEMP 201

/*new Fac */ BEGIN

MOVE TEMP 203 HALLOCATE 4

MOVE TEMP 204 HALLOCATE 4

HSTORE TEMP 203 0 TEMP 204

HSTORE TEMP 204 0 Fac_ComputeFac

RETURN TEMP 203 END

MOVE TEMP 205 10

HLOAD TEMP 202 TEMP 201 0

HLOAD TEMP 202 TEMP 202 0

RETURN TEMP 202 END (

TEMP 201

TEMP 205

)

/*PRINT*/

END

Fac_ComputeFac [ 2 ] BEGIN

/* if */ CJUMP LT TEMP 1 1 L101

MOVE TEMP 2 1

/* else */ JUMP L102

L101 MOVE TEMP 2 TIMES TEMP 1

CALL BEGIN

MOVE TEMP 206 TEMP 0 MOVE TEMP 208 MINUS TEMP 1 1

HLOAD TEMP 207 TEMP 206 0

HLOAD TEMP 207 TEMP 207 0

RETURN TEMP 207 END (

TEMP 206

TEMP 208

)

/* endif */ L102 NOOP

RETURN

TEMP 2

/* end Fac_ComputeFac */ END

In this task, we are going to transfer Piglet into Spiglet, which is a subset of Piglet. Spiglet is closer to three address code since it eliminates recursive code from Piglet.

The grammar for Spiglet differs from that of Piglet in the following ways:

-

The recursive expression is prohibited

-

There are only four types of expression

Exp:- Simple expression

SimpleExp, which consists of temporary variableTemp, integer literalIntegerLiteral, and labelLabel. - Function calling

Call - Memory allocation

HAllocate - Binary operation

BinOp

- Simple expression

-

Note that

StmtExpis no longer an expressionExpin Spiglet. The main challenge in this task is to transferStmtExpinto a series of equivalent instructions. -

Here we summarize all the BNFs that are different in Piglet and Spiglet:

Piglet Spiglet CJumpStmt ::= "CJUMP" Exp Label CJumpStmt ::= "CJUMP" Temp Label HStoreStmt ::= "HSTORE" Exp IntegerLiteral Exp HStoreStmt ::= "HSTORE" Temp IntegerLiteral Exp HLoadStmt := "HLOAD" Temp Exp IntegerLiteral HLoadStmt := "HLOAD" Temp Temp IntegerLiteral PrintStmt ::= "PRINT" Exp PrintStmt ::= "PRINT" SimpleExp Exp ::= StmtExp | Call | HAllocate | BinOp | Temp | IntegerLiteral | Label Exp ::= Call | HAllocate | BinOp | SimpleExp StmtExp ::= "BEGIN" StmtList "RETURN" Exp "END" StmtExp ::= "BEGIN" StmtList "RETURN" SimpleExp "END" Call ::= "CALL" Exp "(" ( Exp )* ")" Call ::= "CALL" SimpleExp "(" ( Temp )* ")" HAllocate ::= "HALLOCATE" Exp HAllocate ::= "HALLOCATE" SimpleExp BinOp ::= Operator Exp Exp BinOp ::= Operator Temp SimpleExp SimpleExp ::= Temp | IntegerLiteral | Label From this chart, we can see only move statement

MoveStmtcan use expressionExpas a source. Printing statementPrintStmtuses simple expressionSimpleExpas a source. Other statements use temporary variables for they resemble registers in the following section.

Firstly, since we may use new temporary variables, we scan the whole program and find the next available temporary variable index.

Secondly, we scan the whole abstract syntax tree again. In this pass, the main challenge is that at any node whose BNF consists of Exp, we should judge whether this Exp should be transform to SimpleExp or TEMP. If so, we should leverage MOVE statement to transfer the result of this Exp into newly added temporary variable, and the replace the this Exp in original statement by this new temporary variable.

In our implementation, we scan the whole abstract tree in depth-first order. The difference from the common depth-first visitor is that, when visiting any node, a parameter is carried in to identify the expected return token of this node. Certainly, for some node types like Goal and PrintStmt, we don’t have expected return token. However, for other node types like StmtExp, we have an expected return token.

To be specified, all the tokens are derived from an interface with method ToString(), which return the corresponding string form of the token. The classification of the expected token is the same as that of Exp.

- Token

- ExpToken

- SimpleExpToken

- TempToken

- IntegerLiteralToken

- LabelToken

- CallToken

- HAllocateToken

- BinOpToken

- SimpleExpToken

- ExpToken

/**

* Spiglet Token

*/

interface Token {

public String toString();

}

class ExpToken implements Token {

}

class SimpleExpToken extends ExpToken {

}

class CallToken extends ExpToken {

String tokenImage;

CallToken(String tokenImage) {

this.tokenImage = tokenImage;

}

public String toString() {

return tokenImage;

}

}

class HAllocateToken extends ExpToken {

String tokenImage;

HAllocateToken(String tokenImage) {

this.tokenImage = tokenImage;

}

public String toString() {

return tokenImage;

}

}

class BinOpToken extends ExpToken {

String tokenImage;

BinOpToken(String tokenImage) {

this.tokenImage = tokenImage;

}

public String toString() {

return tokenImage;

}

}

class TempToken extends SimpleExpToken {

String tokenImage;

TempToken() {

}

TempToken(String tokenImage) {

this.tokenImage = tokenImage;

}

TempToken(Temp n) {

this.tokenImage = "TEMP " + n.f1.f0.toString();

}

public String toString() {

return tokenImage;

}

}

class IntegerLiteralToken extends SimpleExpToken {

int integerLiteral;

IntegerLiteralToken(IntegerLiteral n) {

this.integerLiteral = Integer.parseInt(n.f0.toString());

}

public String toString() {

return Integer.toString(integerLiteral);

}

}

class LabelToken extends SimpleExpToken {

String label;

LabelToken() {

}

LabelToken(String label) {

this.label = label;

}

LabelToken(Label n) {

this.label = n.f0.toString();

}

public String toString() {

return label;

}

}Take HLoadStmt statement as an example. The BNFs of HLoadStmt in these two IR are:

- Piglet syntax

HLoadStmt ::= "HLOAD" Temp Exp IntegerLiteral - Spiglet syntax

HLoadStmt ::= "HLOAD" Temp Temp IntegerLiteral

/**

* Piglet syntax: HLoadStmt ::= "HLOAD" Temp Exp IntegerLiteral

* Spiglet syntax: HLoadStmt ::= "HLOAD" Temp Temp IntegerLiteral

*/

public Token visit(HLoadStmt n, PigletTranslatorAugs argus) {

Emitter e = argus.getEmitter();

Token expectedToken = argus.getExpectedToken();

if (expectedToken == null) {

Token token1 = n.f1.accept(this, new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new TempToken()));

Token token2 = n.f2.accept(this, new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new TempToken()));

e.emitBuf(n.f0.toString(), token1.toString(), token2.toString(), n.f3.f0.toString());

return null;

}

Info.panic("Never reach here!");

return null;

}In above code snippet, n refers to current HLoadStmt Node in AST. We expect the n.f1 to be an temporary variable, so we visit n.f1 with parameters new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new TempToken()). The same goes for n.f2.

Token token1 = n.f1.accept(this, new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new TempToken()));

Token token2 = n.f2.accept(this, new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new TempToken()));Then we call the ToString() method of the return token token1 and token2, without knowing whether the corresponding subtree in AST is Temp or not. Note that the transfer have been emitted during the visit to the subtree.

Let's see what happens when the expected return token is different from the current type. If current return token type is not derived from the expected return token type, we should adjust the current node through a series of instructions and return the expected token by the move statement. For example, when visiting Hallocate node,

public Token visit(HAllocate n, PigletTranslatorAugs argus) {

Emitter e = argus.getEmitter();

Token expectedToken = argus.getExpectedToken();

Token token1 = n.f1.accept(this, new PigletTranslatorAugs(e, new SimpleExpToken()));

StringBuffer buf = new StringBuffer();

buf.append("HALLOCATE", token1.toString());

if (expectedToken == null) {

e.emit(buf.toString());

return null;

} else if (expectedToken.getClass().isAssignableFrom(HAllocateToken.class)) {

return new HAllocateToken(buf.toString());

} else {

/**

* MOVE TEMP 1 HALLOCATE SimpleExp

*/

Token rv = new TempToken(e.newTemp());

buf.prepend(rv.toString());

buf.prepend("MOVE");

e.emit(buf.toString());

return rv;

}

}-

If no expected return token, return

null:if (expectedToken == null) { e.emit(buf.toString()); return null; }

-

if the expected return token is derived from

HallocateToken, returnHallocateTokendirectly.else if (expectedToken.getClass().isAssignableFrom(HAllocateToken.class)) { return new HAllocateToken(buf.toString()); }

-

Otherwise, we leverage

MOVEstatement to transfer the result of thisExpinto newly added temporary variable, and return the this newly added temporary variable.else { /** * MOVE TEMP 1 CAll SimpleExp (...) */ Token rv = new TempToken(e.newTemp()); buf.prepend(rv.toString()); buf.prepend("MOVE"); e.emit(buf.toString()); return rv; }

Since we visit the AST in depth first order, as for recursive statement, we will emit its internal statement firstly during on-the-fly translation.

Register allocation is one of the most fundamental problems in compiler design. This is because every machine has a finite (usually scarce) number of registers to hold the temporal variables in the IR code. Therefore, if there are one or more temporal variables that can be assigned a machine register, we have to spill some of temporaries in memory instead of registers.

It is not an easy task to minimize the number of temporaries that have to be spilled. The difficulty rises from the fact that this job is a NPC problem. To see why, consider a register interference graph (RIG) in which each node represents a temporary value and each edge (

Generally, linear scan and second-chance bin packing are two popular approaches that widely used in practice. The major advantage is simplicity. It runs in linear time and produce good code in many circumstances (e.g., JIT compilers like Java HotSpot). Unfortunately, these methods trade some performance for simplicity and efficiency.

The Chaitin's Algorithm, a method based on RIG, outperforms linear scan and second-chance bin packing. It is used in production compilers like GCC. Although this algorithm a based on the NP-hard graph coloring problem, it produces excellent assignment of variables to registers. It intelligently and heuristically gives an approximation to the NPC problem.

In the lab, we are going to implement a variant of Chaitin's Algorithm for the translation form Spiglet language to Kanga language. In the example testcases, our implementation always produces shorter and cleaner code than the example output.

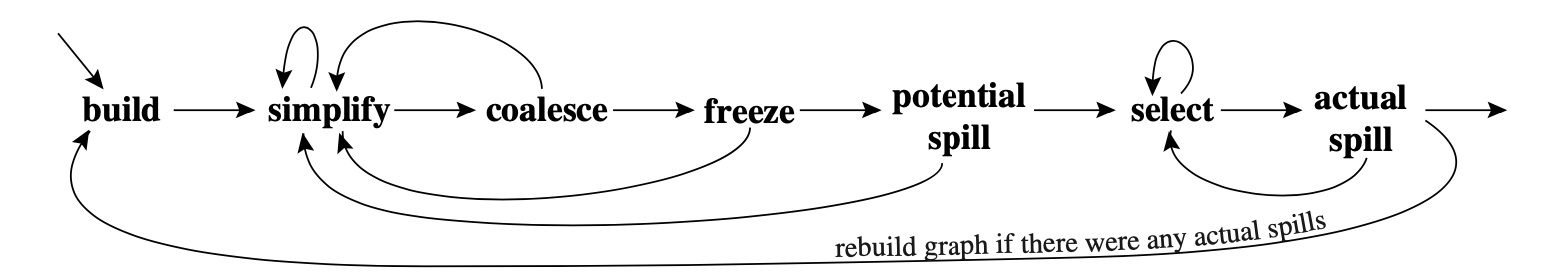

Most of our implementation design aspects follow what is described in Modern Compiler Implementation in Java (2nd edition). The main phases are shown in the figure below.

Build: First we have to do the liveness analysis. We takes each instruction as a basic block and solve the following equations:

Then we build the RIG. Add an edge for two temporaries if they are in the same

One the flip side, we must takes pre-allocated registers (a.k.a pre-colored nodes) into consideration. There are two rules for these registers. First, pre-allocated registers interfere with each other. Second, temporaries that live across a function call interfere with all caller-saved registers. Below is the code snippet.

// pre-allocated registers

for (int i = 0; i < TempReg.NUM_REG; i++) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < TempReg.NUM_REG; j++) {

TempReg ri = TempReg.getSpecial(i);

TempReg rj = TempReg.getSpecial(j);

rig.addInterference(ri, rj);

}

}

// caller-saved registers

for (Instruction i = dummyFirst.next; i != dummyLast; i = i.next) {

if (i instanceof InstrCall) {

for (TempReg r : i.in) {

if (i.out.contains(r) && !i.def.contains(r)) {

for (int j = TempReg.CALLEE_SAVED_REG; j < TempReg.NUM_REG; j++) {

rig.addInterference(r, TempReg.getSpecial(j));

}

}

}

}

}In addition, we leverage the algorithm to save the callee-save registers intelligently by moving a callee-save register to a fresh temporary. If there is register pressure in a function, the temporary will spill; otherwise it will be coalesced with the corresponding callee-save register and the MOVE instructions will be eliminated by the procedure that we will soon introduce.

FOO [2][0][0]

MOVE TEMP 1 s0

MOVE TEMP 2 s1

MOVE TEMP 3 s2

... // the body of the function

MOVE s2 TEMP 3

MOVE s1 TEMP 2

MOVE s0 TEMP 1

Simplify: Remove the nodes that is less than MOVE r1 r2 (r1 and r2 are registers).

Coalesce: Coalescing means merge two nodes into a new node whose edges are the union of those of the nodes being replaced. This approach is important for eliminating move instructions. We wish to coalesce only where it is safe to do so, that is, where the coalescing will not render the graph uncolorable. Both of the following strategies are safe:

- Briggs: Nodes

aandbcan be coalesced if the resulting nodeabwill have fewer than$K$ neighbors. - George: Nodes

aandbcan be coalesced if, for every neighbortofa, eithertalready interferes withb.

To maintain the coalescing relation, we resort to disjoint set union (DSU) that is a data structure tracking a set of elements partitioned into a number of disjoint (non-overlapping) subsets. Here the "elements" are all the original nodes and the "disjoint subset" is the union of the coalesced nodes. We use the field alias to represent "the parent" of a subset.

static class MoveRelated {

Node n1, n2;

MoveRelated(Node n1, Node n2) {

this.n1 = n1;

this.n2 = n2;

}

void update() {

while (n1.alias != null) {

n1 = n1.alias;

}

while (n2.alias != null) {

n2 = n2.alias;

}

}

}Freeze: give up hope of coalescing a move and "simplify" may continue.

Spill: select a node for potential spilling and push it on the stack.

Select: Pop the entire stack, assigning colors.

Actual Spill: If we cannot assign a color to node n, we rewrite the program to spill the corresponding temporary. First, we spare a new address for store/fetch the temporary. Second, add store it on the stack after it is defined and fetch it before it is used by an expression. Below is an example:

MOVE TEMP 1 ADD TEMP 2 TEMP 1

After TEMP 1 is spilled (assume we use a brand new temporary TEMP 5 for this spilling and the memory address is SPILLEDARG 10):

ALOAD TEMP 5 SPILLEDARG 10

MOVE TEMP5 ADD TEMP2 TEMP 5

ASTORE SPILLEDARG 10 TEMP 5

In the example testcases, our implementation always produces shorter and cleaner code than the example output. This mainly thanks to the coalescing operation. For code,

Tree_SetRight [2]

BEGIN

HSTORE TEMP 0 8 TEMP 1

MOVE TEMP 446 1

RETURN

TEMP 446

END

the example gives:

Tree_SetRight [2][2][0]

ASTORE SPILLEDARG 0 s0

ASTORE SPILLEDARG 1 s1

MOVE s0 a0

MOVE s1 a1

HSTORE s0 8 s1

MOVE t0 1

MOVE v0 t0

ALOAD s0 SPILLEDARG 0

ALOAD s1 SPILLEDARG 1

END

ours yields code:

Tree_SetRight [2] [0] [0]

HSTORE a0 8 a1

MOVE v0 1

END

We can see that our algorithm efficiently uses the valuable registers.

Label Rewrite: Rewrite the code

JUMP L2

...

JUMP L1

...

L2 NOOP

L1 NOOP

as

JUMP L3

...

JUMP L3

...

L3 NOOP

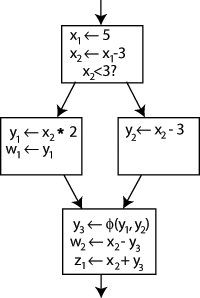

Static Single-Assignment (SSA) form: Rewrite the program so that each variable has only one definition in the program text.

It is clear which definition each use is referring to, except for one case: both uses of y in the bottom block could be referring to either y1 or y2, depending on which path the control flow took.

To resolve this, a special statement is inserted in the last block, called a

$\phi$ function. This statement will generate a new definition of y called y3 by "choosing" either y1 or y2, depending on the control flow in the past. (Wikipedia)

Heuristic Spilling: Our implementation spill the first node that can be colored. In fact, we can select the node to be spilled in a heuristic manner. That is, we first calculate spill priorities and spill the node with lowest priorities. The priority can be defined as $$ \frac {\text{uses outsides loop}+\text{uses insides loop} \times 10} {\text{Degree}} $$

The priority value represents the gained performance if we don't spill this node.

In this task, we are going to transfer IR representation Kanga into assembly language MIPS. There are two main challenges in this task: system call(HALLOCATE, PRINT, ERROR)and stack maintenance. We will explain the respective solutions towards these challenges in the following sections.

There are three types of instructions in Kanga that must be implemented by system call, namely heap memory allocation HALLOCATE, printing instruction PRINT and error instruction ERROR. Generally, the function number and the parameter of the system call are specified by register v0 and a0 respectively. Meanwhile, the return value is stored in register v0 if any.

| Function | Function Number v0 |

Parameter | Return Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Print Integer | 1 | a0 = integer to be printed |

N/A |

| Print String | 4 | a0 = first address of the string to be printed |

N/A |

| Allocate Heap Memory | 9 | a0 = number of bytes to be allocated |

v0 = first address of allocated memory |

| Exit | 10 | N/A | N/A |

.text

.globl _halloc

_halloc :

li $v0, 9

syscall

j $ra

.text

.globl _print

_print :

li $v0, 1

syscall

la $a0, newl

li $v0, 4

syscall

j $ra

.text

.globl _error

_error :

la $a0, str_er

li $v0, 4

syscall

li $v0, 10

syscall

.data

.align 0

newl :

.asciiz "\n"

.data

.align 0

str_er :

.asciiz " ERROR: abnormal termination\n" In our implementation, these system calls are wrapped into procedures. For example, ERROR instruction is translated into

la $a0, str_er # the first address of error string

li $v0, 4 # function number(Print String)

syscall

li $v0, 10 # function number(Exit)

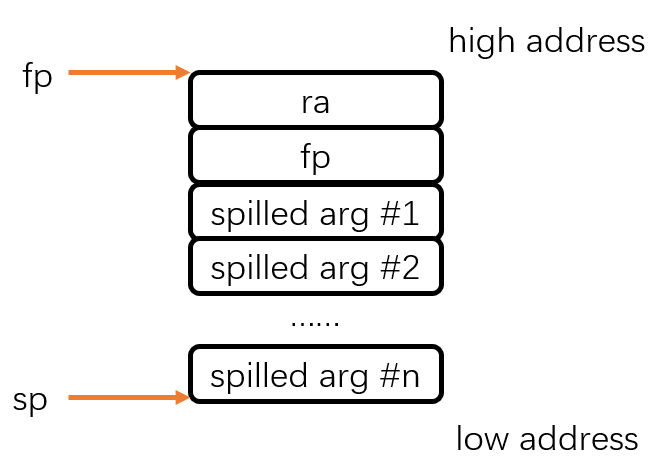

syscallAn interesting question about stack maintenance is the the order of spilled parameters stored in stack from low address to high address.

Should we store the spilled parameters in order from lower address to higher address?

Note that the spilled parameters are passed vis PassArgStmt before CallStmt. According to halting problem, actually we have no idea what is the following running continuation after PassArgStmt, so we actually couldn’t find which CallStmt this spilled parameter is passed into, let alone the totally number of the spilled parameters of the called procedure.

Therefore, it is unreasonable to store the the spilled parameters in order from lower address to higher address. The spilled parameters should stored in reversed order as in following illustration.

The layout of stack frame is:

Take the procedure Fac_ComputeFac [2][3][2] as an example, when entering this procedure:

.text

.globl Fac_ComputeFac

Fac_ComputeFac :

sw $fp, -8($sp)

move $fp, $sp

subu $sp, $sp, 20

sw $ra, -4($fp) When leaving this procedure:

lw $ra, -4($fp)

lw $fp, 12($sp)

addu $sp, $sp, 20

j $ra - Gettysburg CS 374

- Software and Documentation

- Standford cs143

- Modern Compiler Implementation in Java (2nd edition)