-

C++11 compiler, e.g GNU g++ / Intel icc. In my experiments I used the Intel compiler for perfomance reasons.

-

FastFlow, a library offering high-performance parallel patterns and building blocks in C++.

Modify src/Makefile to provide the name of the chosen C++11 compiler and the home directory to FastFlow.

Then cd src/, and run make to compile the code for different configurations and version of the source code. Feel free to modify it with additional options for different architectures.

Once the code has been compiled, the generated binary code can be run provided with the following arguments <n> <m> <d>, where n is the size of the problem, i.e. the number of the queens, m is the number of workers and d is the depth where to stop sequential recursion.

The n-queens problems stems from a generalization of the eight queens puzzle.

In the following will be introduced two parallel implementations of a Divide-And-Conquer algorithm to solve the n-queens problem, using different computational models. The first using the FastFlow framework, and the second pure C++1 Threads. The experiments I made, were ran on an Intel Xeon architecture equipped with two Intel Xeon Phi co-processors.

Before going further into the details of the sequential algorithm, we introduce the following definition

Def.1: Let an abstract tree model all possible configurations, or states, a chessboard B of size n x n, and with n queens, it can assume. The root node, with height h=0, represents the empty configuration. A path from the root node to a generic internal node at height h > 0, represents a partial configuration of B with h <= n queens. Furthermore, the generic node represents the position (i, j) in B, assuming B to be indexed using a matrix-like notation, in which it can ben found a queen. Thus, the number of paths of size n, namely all possible permutations of the n queens is given by P\left(n\right) = \frac{n^{2}!}{\left(n^{2} - n\right)!n!}

The naive implementation of the sequential algorithm simply generates all the P(n) states to verify which solution satifies the constraints of the n-queens puzzle.

In order to reduce time complexity, it can be found that during the generation of the states, it can be forced to have that no queen can be found on the diagonal line or the horizontal line of any other queen. To that end, it can be used a simple array of size n. Let R be an array with n components such that

R: Q \rightarrow C

where Q = {1, ..., n} is the set of labels of the queens, and C = {1, ..., n} is the set of column indexes of the chessboard. Then, if R(i) = j then queen i is in position B_{ij}. By definition, only one queen can be found in every row and in every column. Then, it matters only of verifying which of the O(n!) permutations of array R satisfy the aforementioned constrain over the diagonals, namely

\| R(i+d) - R(i) \| \neq d, \forall i, d. i = 1, ..., n-d, d = 1, ..., n-1

The exploration of the tree of solutions proceeds only in the partial paths, i.e. of height h <= n, satisfying previousg equation. Also, at each step of the algorithm, R can be represented using a bit array (cols) as showed in the following image

Array cols encodes the information about which columns are available after i-th queen has been placed. Furthermore, as you can see in the above image, the information on which positions are free in the (i+1)-th row is given by the bit array poss, derived by cols and arrays ld and rd, indicating, respectively, the occupied left and right diagonals in the (i+1)-th row.

Thus, the sequential algorithm can be expressed as the following recursive function

void treeExploring(int ld, int cols, int rd){

if(cols == mask){

count++;

}

int poss = ~(ld | cols | rd) & mask;

while(poss){

int lsb = poss & -poss;

poss -= lsb;

treeExploring( (ld|lsb)<<1, (cols|lsb), (rd|lsb)>>1 );

}

}The computational cost is given by

t_{seq} = O(n!)

The sequential algorithm follows the Divide-and-Conquer (DaC) paradigm: the problem is recursively split into sub-problems until a base case condition on the size of the sub-problem is met for solving it sequentially. Such a paradigm is embarassingly parallel, to be parallelised we can use the master-work framework: there's a processing element (PE) named as the emitter (E), that recursively divides the problem into smaller and independent problems, i.e. easy to solve and with no dependence on the results of other sub-problems is required. The emitter node has to generate sub-trees (implicitly implemented by array R), each of size 2 <= d <= n. Such partial paths, are redistributed to m PE worker (w) that have to conquer such sub-problems, namely finding which of them satisfies the condition (2). Furthermore, there is a PE collector (C) that awaits for worker nodes to complete in order to combine (reduce) partial solutions, i.e. counting how many configurations of the chessboard solve the puzzle.

The selection of the parameter 2 <= d <= n, namely the base case in which to stop the recursion, is particularly important. To better understand that, let's see the cost model of the computational graph of the parallel application as described in the introduction to the parallel algorithm. The ideal service time of the parallel graph is given by

t_{farm} = max \{ t_{e}, \frac{t_{w}}{m}, t_{c} \}

where

t_{e} = O\left(d!\right)

t_{w} = O\left((n-d)!\right)

t_{c} = O\left(m\right)

they define, respectively, the service times of the emitter E, of the generic worker w_{j} and of the collector node C. In the case 2 <= d <= n/2, we have

t_{farm} = O\left( \frac{(n-d)!}{m} \right).

That means that the conquering part represents the bottleneck of the whole graph. We could relax the analysis of the problem, considering only the first part of the graph, i.e E-w, since the term introduced by node C is negligible. Under such hypotheses, and considering a round-robin policy to redistribute tasks among worker nodes, the following relation on the queues utilization factor holds

\rho = O\left( \frac{(n-d)!}{T_{A}} \right) \geq 1

where T_A = O\left( m t_{e} \right) being E a sequential node. Thus, from the previous equation, we have that the bottleneck can be eliminated if and only if the number of the worker is the following

m_{opt} = \left \lceil{\frac{(n-d)!}{d!}}\right \rceil .

In a more realistic setting, we expect the speedup to grow linearly in the number of available PEs. Instead, in the case n/2 <= d <= n, the computation tends to be more fine grained, but end up having t_{farm} \approx t_e.

Let now take into account the impact of the communication latencies. The threaded parallel application implements each of the m arcs {(E, w_j)} using queues: each worker shares a queue with the emitter E. Then we have

t_e = O(d!) + t_{synch}

t_w = O((n-d)!) + t_{synch}.

The term t_{synch} represents the latency given by the mechanisms of synchronization to access the shared memory between (E, w_j). The introduction of m shared queues makes possible to implement a round robin policy to redistribute tasks among workers, solving thus the load-balancing problem. It is worth mentioning, that both in the FastFlow and C++11 threaded version of the application, the generinc worker node accumulates the partial solutions in a counter in its local memory. And thus, the collector node C, after all worker have been terminated, reduces all partial accumulated solutions simply by accessing all the local memories of the single worker nodes. In that way, communications latencies are reduced to the minimum, without incurring into synchronization mechanisms, making thus the conquering part totally independent. That solution, is motivated also in part by the fact that the reduce operation is negligible.

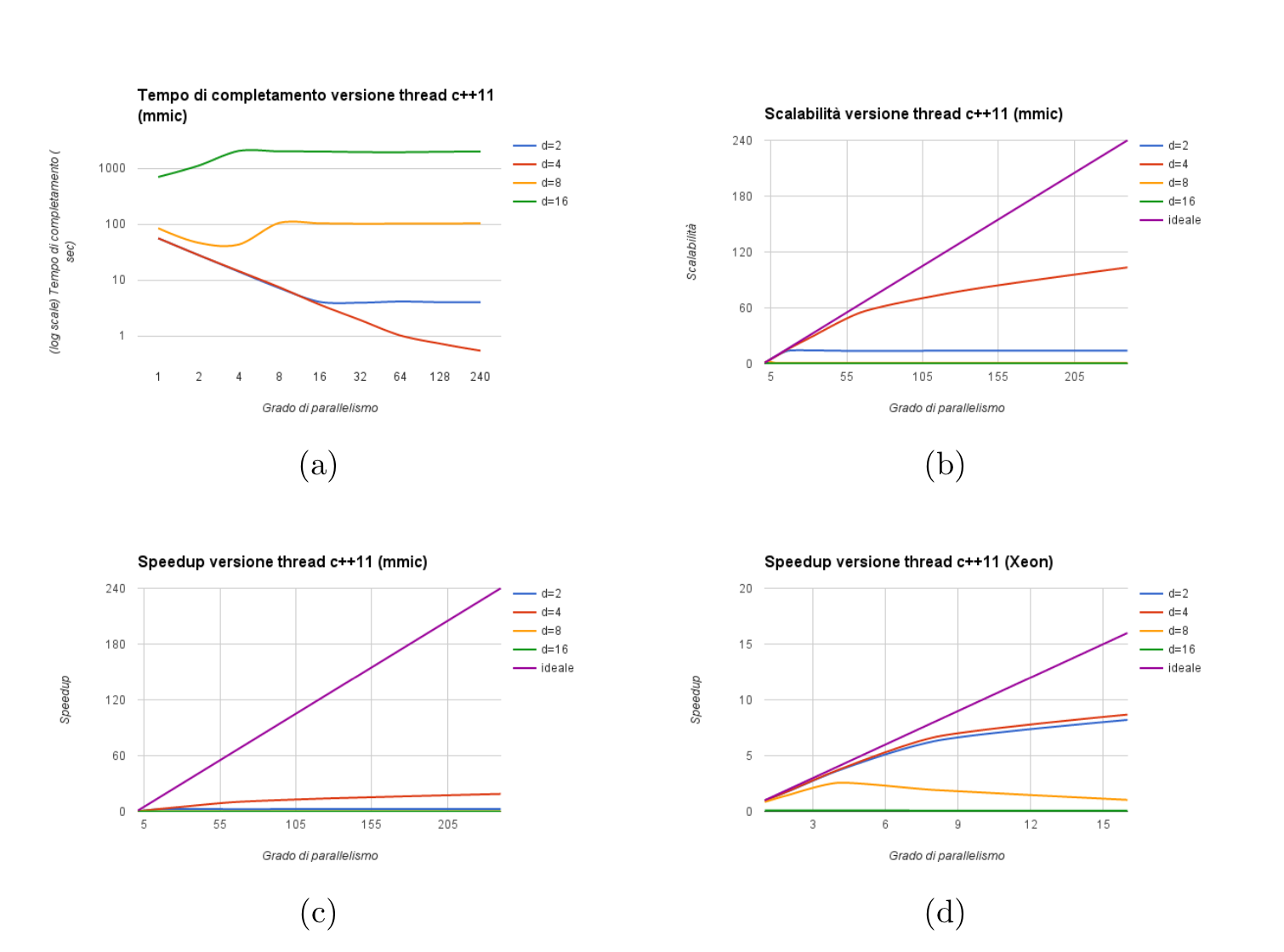

Experiments were run on an Intel Xeon architecture equipped with 8 cores @ 2Ghz, and with hyperthreading can be allocated up to 16 threads. Such an architecture hosts 2 co-processors based on the Intel Many Integrated Core (mic) architecture, named as Xeon Phi. Each co-processor is equipped with 60 cores @ 1Ghz, and with hyperthreading can be allocated a total of 240 threads. The parallel application, both the FastFlow and C++11 Threaded versions, has been compiled using the Intel compiler (ic) ver. 15.0.2. The size of the problem is n=16 with different values of d=2,4,8,16. Below the plots relative to the completion time, the scalability and the speedup on the mic (a,b,c) architecture, and the speedup on the host (d) architecture.

In the following image can be seen, instead, the efficiency of the FastFlow parallel application on the mic (a) and the host (b) architecture.

Plots relative to the completion time, scalability and speedup of the C++11 threaded version of the parallel application, are showed below

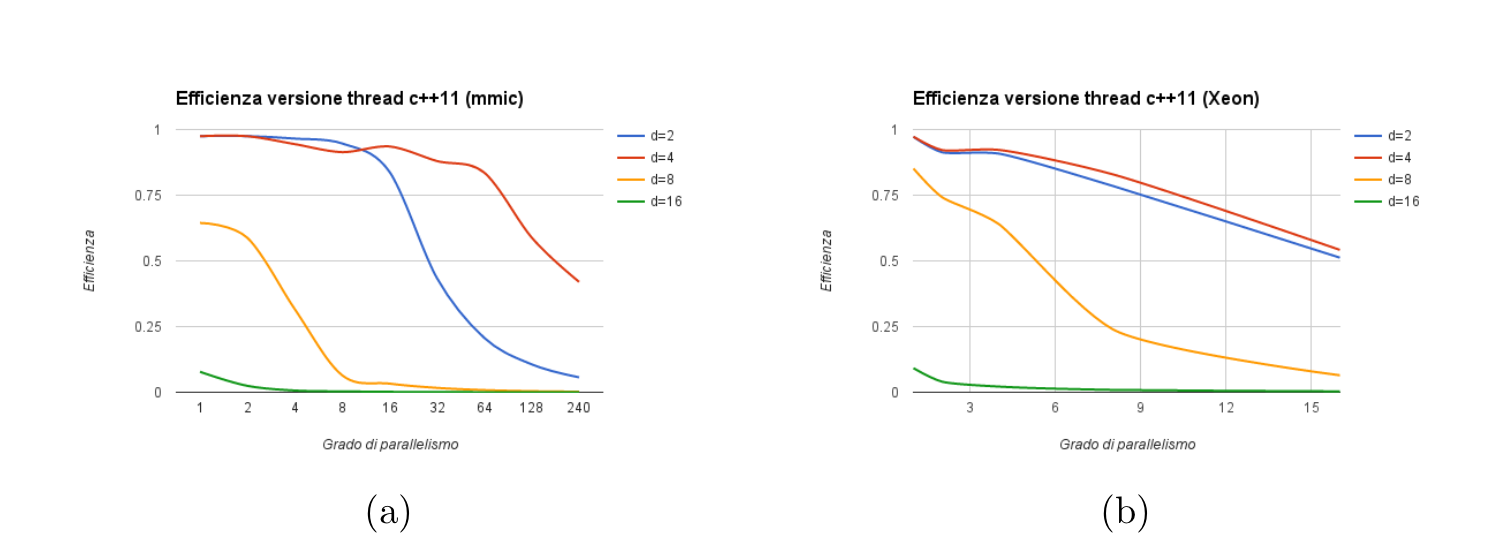

As for the FastFlow version, we also show the efficiency of the threaded version as can be seen in the following plots

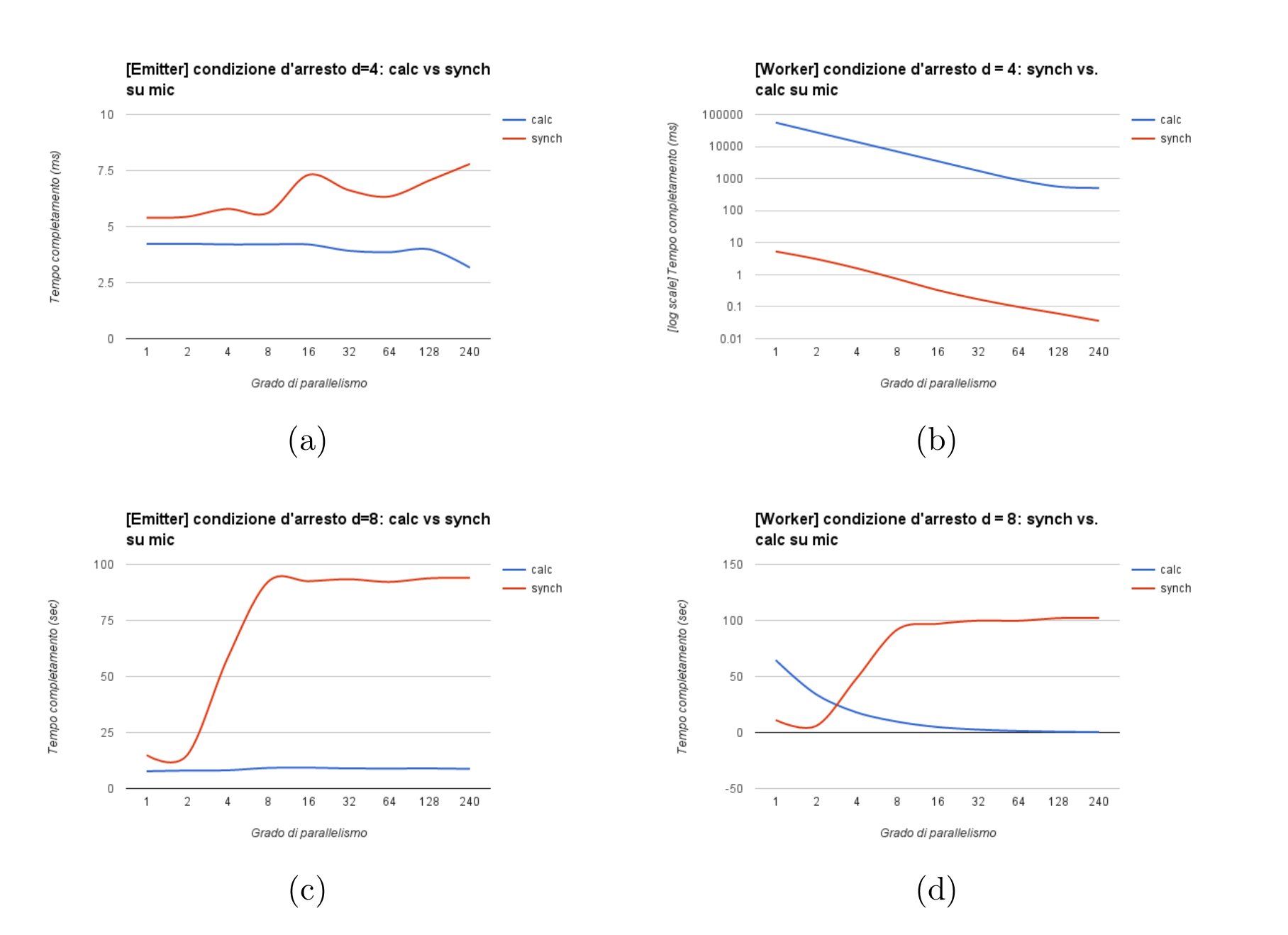

For both the versions, the best sequential time (necessary to compute the scalability) has been chosen to be the one obtained on the host architecture. As we expected, the maximum scalability is obtained for d < n/2. Sadly, the theoretical optimum can't be reached due to intrinsic reasons of the architecture were the code is run, and as we can observe, from the time the hyperthreading shows up the scalability starts decreasing, thus no more than 40% to 50% of the available computing resources are used. For d >= n/2, instead, there is no scalability, in fact, as we have seen in the theoretical cost model, the computational graph behaves as single sequential module. In the following plots, we show the results of the impact of communication latencies in the C++11 threaded version.

As we can see, for d=4, we have t_{synch} \approx 0, namely, in the completion time of the generic worker the cost communication is completely negligible. Instead, for d=8, we have t_e, t_w \approx t_{synch}, namely, the generic worker spends more time waiting for new tasks than to conquer the problem. In conclusion, we can say that in the attempt to make the computation more fine grained, namely for increasing values of parameter d, the number of needed PEs tends to decrease. That is a consequence of the fact that the computational graph behaves, for increasing values of d, as a sequential module. Furthermore, the communication latancies are the dominant factor.