Remember, a few hours of trial and error can save you several minutes of looking at the README.

This repository contains two documents:

-

This README in Markdown format. Using

pandocwith the Eisvogel template (more on that later), it is converted into a PDF and made available for download (see also the badge on top of the project homepage):The README covers git and Continuous Delivery, using Docker.

-

A LaTeX document, usable as a cookbook (different "recipes" to achieve various things in LaTeX) and also as a template.

The LaTeX Cookbook PDF covers LaTeX-specific topics. It is also available for download:

That being said, onto git. This README will not be exhaustive; there are numerous great tools to learn git out there. This is just a brief introduction. Eventually, following all the steps, a number of advantages will come to light:

-

SSOT: a Single Source Of Truth for data. No more file trees looking like this:

directory │ a.txt │ help.me.please │ Important-Document_2018_version1.pdf │ Important-Document_2018_version2.pdf │ Important-Document_2018_version3_final.pdf │ Important-Document_2018_version3_final_really.pdf │ Important-Document_2018_version3_final_really_I-promise.pdf │ Important-Document_2018_versionA.pdf │ Important-Document_2019-03-56.pdf │ Important-Document_2019-03-56_corrections_John-Doe.pdf │ Important-Document_2019-03-56_corrections_John-Doe_v2.pdf │ invoice.docx │ test - Copy (2).tex │ test - Copy.tex │ test.tex │ └───old_stuff Screenshot 1999-09-03-15-23-15(1).bmp Screenshot 1999-09-03-15-23-15(2).bmp Screenshot 1999-09-03-15-23-15(3).bmp Screenshot 1999-09-03-15-23-15(3)_edited.bmp Screenshot 1999-09-03-15-23-15.bmpInstead, there is one working copy looking like this:

directory │ .git (a hidden directory) │ a.txt │ Important-Document.pdf │ Properly-Named-Invoice.docxassuming that

a.txtis actually needed. All the old junk and redundant copies have been pruned. However, nothing was lost. The entire history is contained in git, a Version Control System. The history is readily summoned anytime, if so required. Git calls this its log. Git works best (some would say only) on text-based files, but it can deal with images, PDFs etc., too.The history and everything else git needs is contained in its

.gitdirectory, which is hidden on both Linux and Windows. Everything else indirectory, so in this casea.txt,Important-Document.pdfandProperly-Named-Invoice.docx, is accessible as usual. There is no difference to how you would normally work with these files. They are on your local disk. Together, they are called the working tree.Therefore (provided that git is used correctly):

- Duplicate files are gone,

- The art of cumbersome file naming will finally be forgotten,

- Old stuff can be safely deleted; this cleans up the working tree and makes it clear which files are no longer needed. Only the currently needed files are visible, the rest is (retrievable!) history.

-

File versioning and the ability to exactly match outputs (PDFs) to the source code that generated them.

-

Accelerated bug fixing through

git bisect, a binary search algorithm that helps pinpoint commits (stages of development) that introduced regressions. -

Collaboration: each contributor has a version of the source on their local machine. Adjustments are made there, and sent to a central, online repository if they are considered ready to be published. Git can also be used in a distributed fashion (its original strong suit), but we assume a remote repository on GitLab (which is very much similar to GitHub). Developers can then also fetch the latest changes from the remote and incorporate them into their local copy.

Do not confuse GitHub, GitLab and others with the tool itself, git. Microsoft's GitHub is not synonymous to git. A crude, mostly wrong analogy would be: OneDrive is the platform you do collaboration, version control and sharing on. This is like GitHub (GitLab, ...). Office programs like Microsoft Word are used to create original content. This is like source code, as created in some editor of your choice. Word's built-in revision history, in conjunction with the process of naming files, for example

2020-05-13_Invoice_John-Doe-Comments_Final.docx(ISO-8601 oh yeah baby), would be git. It "only" does the version control, but is not a platform for source code. -

The remote repository also serves as a back-up solution. So do all the distributed local copies. At all points, there will be a workable copy somewhere. In general, git makes losing data extremely hard. If, or rather when, you do get into a fight with git about merging, pulling, rebasing, conflicts and the like, think of it as git protecting you and your work. Often, the reason for git "misbehaving" and making a scene is because it flat-out refuses to conduct an operation that would destroy unsaved changes. In the long run, this behavior is the desired one, as opposed to losing unsaved (in the git-lingo: uncommitted) data.

Download for Windows here. Install it and spam Next without reading the installation and warning prompts, as you always do.

For Linux, apt update && apt install git or whatever.

You likely have it available already.

Then, somewhere on your machine:

# Create empty directory

$ mkdir test

# Go there

$ cd test

# Set up your git credentials; this will show as the 'Author' of your work

$ git config --global user.name "Foo Bar"

$ git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

# Initialize an empty git repository

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in ...

# Create some dummy file

$ echo "Hello World!" > test.txt

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

test.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

# Do as we are told, like good boys:

$ git add .

# There is now a change! The file is ready to be committed, aka "saved" into

# the history.

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: test.txt

$ git commit -m "Initial file!"

[master (root-commit) 3aaded0] Initial file!

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 test.txt

# Have a look at the history up to here:

$ git log --patch

commit 3aaded0365524e9c0cf7c3bc3cb72e1e993def74 (HEAD -> master)

Author: Foo Bar <[email protected]>

Date: Mon Sep 28 15:29:25 2020 +0200

Initial file!

diff --git a/test.txt b/test.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..de39eb0

Binary files /dev/null and b/test.txt differAnd that is the gist of it. Next, you would want to create a project on GitLab or similar and connect that to your local repository. You can then sync changes between the two, enabling collaboration (or a bunch of other advantages if you keep to yourself).

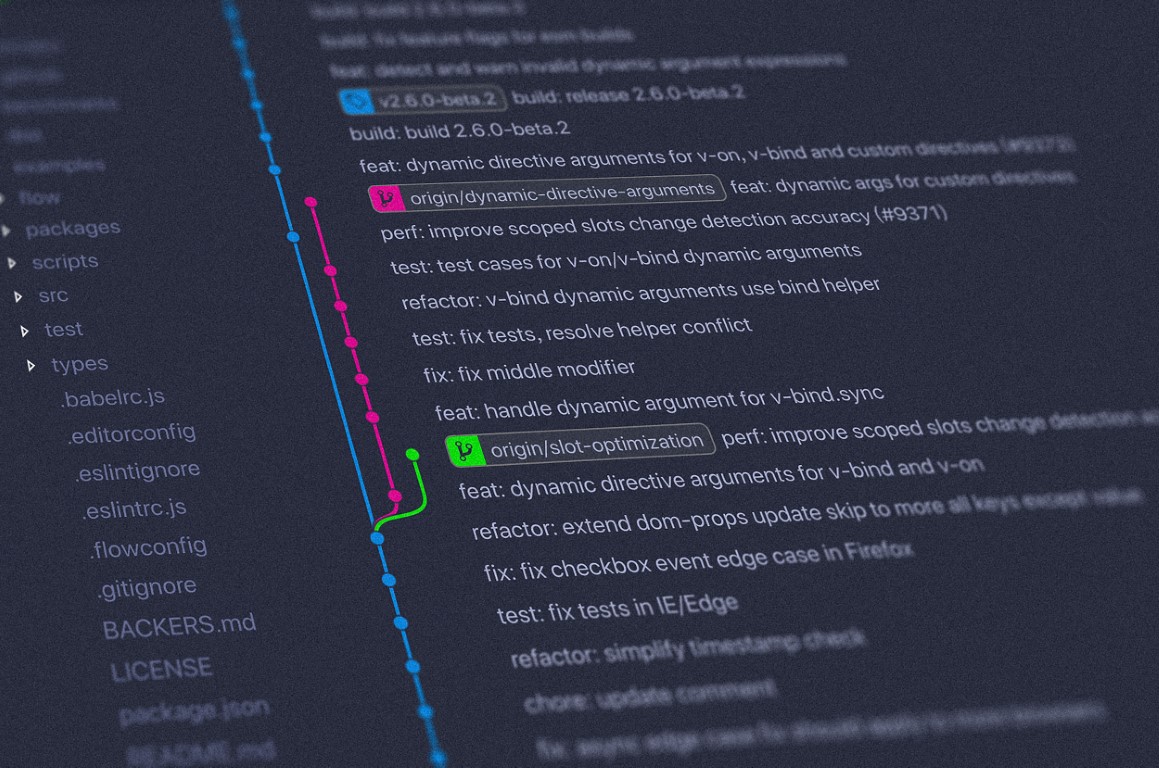

There are numerous git GUIs available. They are great at visualizing the commit history (which can get convoluted, if you're doing it wrong), but also offer all the regular CLI functionality in GUI form. I have nothing to recommend here and am going to distract from this fact using this pretty git GUI image from here:

GitLab is a platform to host git repositories. Projects on there can serve as git remotes. As mentioned, in this sense, it is like Microsoft's GitHub, the first large website to offer such a service (still by far the largest today). We use GitLab here because https://collaborating.tuhh.de/ is an instance of GitLab and therefore freely available to university members.

GitLab offers various features for each project. This includes a Wiki, an issue tracker and pull request management. Pull requests (PRs for short; GitLab calls these Merge Requests) are requests from outside collaborators who have forked and subsequently worked on a project. Forking projects refers to creating a full copy of the project in the own user space of collaborators. As such, they can then work on it, or do whatever else they want. If for example they add a feature, their own copy is now ahead of the original by that feature. To incorporate the changes back to the original, the original repository's maintainers can be requested to pull in the changes. This way, anyone can collaborate and help, without ever interfering with the main development in the original.

Continuous Delivery refers to continuously shipping out the finished "product". In this case, these are the compiled PDFs. This is done with the help of so-called Docker containers. The advantages are:

-

collaborators no longer rely on their local tool chain, but on a unified, common, agreed-upon one. It is (usually) guaranteed to work and leads to the same, reproducible, predictable results for everyone.

Docker (also usable locally, not only on the GitLab platform) helps reproduce results:

-

across space: results from coworkers in your office or from half-way across the globe.

You no longer rely on some obscure, specific machine that happens to be the only one on which compilation (PDF production) works.

-

across time: if fixed versions are specified, Docker images allow programs, processes pipelines etc. from many years ago to run.

-

-

If LaTeX documents become very long, full compilation runs can take dozens of minutes. This is outsourced and silently done on the remote servers, if Continuous Delivery is used. As such, for example, every

git pushto the servers triggers a pipeline which compiles the PDF and offers it for download afterwards. The last part could be called Continuous Deployment, albeit a very basic version.

Docker is a tool providing so-called containers (though wrong, think of them as light-weight virtual machines). These containers provide isolated, well-defined environments for applications to run in. They are created from executing corresponding Docker images. These images are in turn generated using a script-like list of instructions, so-called Dockerfiles.

In summary:

-

a

Dockerfiletext document is created, containing instructions on how the image should look like (like what stuff to install, what to copy where, ...).As a baseline, these instructions often rely on a Debian distribution. As such, all the usual Debian/Linux tools can be accessed, like

bash.An (unrelated) example Dockerfile can look like:

# Dockerfile # Get the latest Debian Slim with Python installed FROM python:slim # Update the Debian package repositories and install a Debian package. # Agree to installation automatically (`-y`)! # This is required because Dockerfiles need to run without user interaction. RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y ffmpeg # Copy a file from the building host into the image COPY requirements.txt . # Run some shell command, as you would in a normal sh/bash environment. # This is a Python-specific command to install Python packages according to some # requirements. RUN pip install -r requirements.txt # Copy more stuff! COPY music-converter/ music-converter/ # This will be the command the image executes if run. # It runs this command as a process and terminates as soon as the process ends # (successfully or otherwise). # Docker is not like a virtual machine: it is intended to run *one* process, then # die. If you need to run it again, just create a new container (instance of a # Docker image). Treat containers as *cattle*, not as a *pet*. The # container-recreation process is light-weight, fast and the way to go. # # Of course, this does not stop anyone from running one *long-running* process # (as in infinity, `while True`-style). This is still a good use-case for Docker # (as are most things!). An example for this is a webserver. ENTRYPOINT [ "python", "-m", "music-converter", "/in", "--destination", "/out" ]

The Dockerfile this project uses for LaTeX stuff is here. It is not as simple, so not as suited for an example.

-

The image is then built accordingly, resulting in a large-ish file that contains an executable environment. For example, if we install a comprehensive

TeXLivedistribution, the image can be more than 2 GB in size.This Docker image can be distributed. In fact, there is Docker Hub, which exists for just this purpose. If you just instruct to run an image called e.g.

alexpovel/latex, without specifying a full URL to somewhere, Docker will look on the Hub for an image of that name (and find it here). All participants of a project can pull images from there, and everyone will be on the same page (alternatively, you can build the image from the Dockerfile).For example, the LaTeX environment for this project requires a whole bunch of setting-up. This can take hours to read up upon, understand, explain, implement and getting to run. In some cases, it will be impossible if some required part of a project conflicts with a pre-existing condition on your machine. For example, project A requires

perlin version6.9.0, but project B requires version4.2.0. This is what Docker is all about: isolation. Whatever is present on your system does not matter, only the Docker image/container contents are relevant.If project member X has version

6.6.6and they proclaim "works for me", but you have1.3.37and it doesn't, and you both cannot change your versions for some other reason... tough luck. This is what Docker is for.Further, if you for example specify

FROM python:3.8.6as your base image, aka provided a so-called tag of3.8.6, it will be that tag in ten years' time still. As such, you nailed the version your process takes place in and requires. Once set up, this will run on virtually any computer running Docker, be it your laptop now or whatever your machine is in ten years. This is especially important for the reproducibility of research. -

Once the image is created, it can be run, creating a container. We can then enter the container and use it like a pretty normal (usually Linux) machine, for example to compile our

texfiles. Other, single commands can also be executed. For example, to compilecookbook.texin PowerShell when thealexpovel/lateximage is available after installing Docker and getting the image (docker pull alexpovel/latex-- if you don't run this beforehand, it will be downloaded automatically when it is missing), run:docker run --rm --volume ${PWD}:/tex alexpovel/latex

Done! For more info, especially the details of the above command, see here. For this to work, you do not have to have anything installed on your machine, only Docker.

One concrete workflow to employ this chain is to have a Dockerfile repository on GitHub,

like this one.

GitHub then integrates with DockerHub.

It allows users to share images.

As such, there is an image called

alexpovel/latex

on DockerHub.

This image was built using the above GitHub Dockerfile and can be downloaded and run,

yielding a live container.

On every git push (that is, on every change) in the GitHub repo, this image is rebuilt.

Given the size of TeXLive, this takes about on hour.

Refer to the

Dockerfile itself

(that Dockerfile is used to compile this very README to PDF via pandoc)

for more details.

For more information on the LaTeX packages mentioned in the Dockerfile repository, refer to the accompanying LaTeX cookbook.

To get the same, or at least a very similar environment running on Windows, the elements can be installed individually:

- MiKTeX; for a closer match to the Docker, install

TeXLive instead:

for a LaTeX distribution with the

lualatex,biber,bib2gls,latexmketc. programs, as well as all LaTeX packages. - Java Runtime Environment:

for

bib2gls, which is in turn used byglossaries-extra. - InkScape:

for the

svgpackage to convert SVGs automatically (absolutely none of thePDF/PDF_TEXnonsense anymore!) - gnuplot:

for

pgfplotsto generate contour plots. - Perl:

for

latexmkto work

(see how annoying, manual and laborious this list is? ... use Docker!)

These are required to compile the LaTeX document.

If InkScape and gnuplot ask to put their respective binaries into the $PATH

environment variable, hit yes.

If they do not, add the path yourself to the directory containing the binaries

(.exe) in Edit environment variables for your account -> Path -> Edit... -> New.

To build anything, we need someone to build for us.

GitLab calls these build-servers runners.

Such a runner does not materialize out of thin air.

Luckily, in the case of collaborating.tuhh.de, runner tanis is available to us.

Enable it (him? her?) for the project on the GitLab project homepage:

Settings -> CI/CD -> Runners -> Enable Shared Runners.

Otherwise, the build process will get 'stuck' indefinitely.

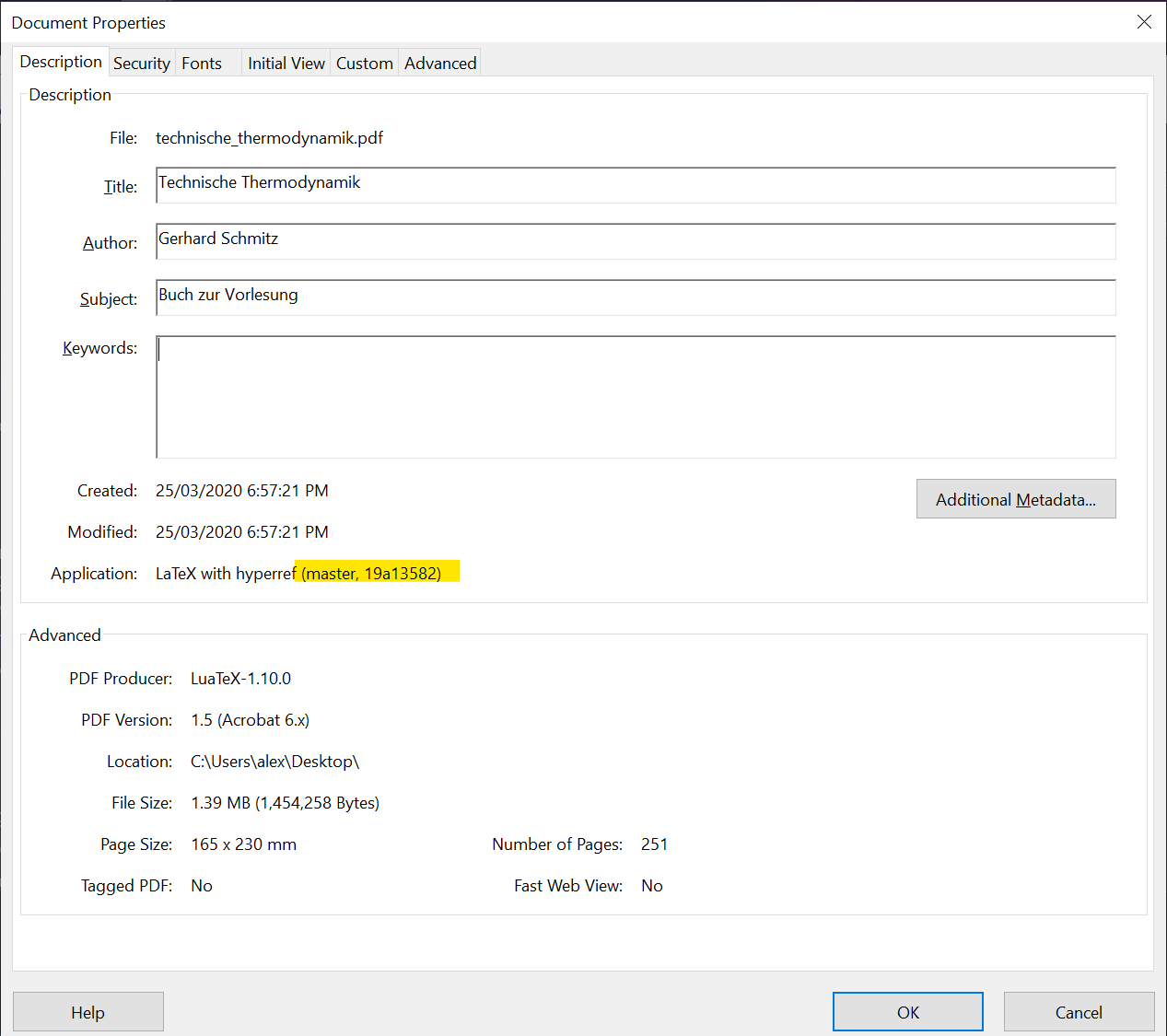

After retrieving a built PDF, it might get lost in the nether. That is, the downloader loses track of what commit it belongs to, or even what release. This is circumvented by injecting the git SHA into the PDF metadata. This allows you to freely hand out PDFs to people, for example for proof-reading or to editors of journals. You will be able to associate and pinpoint their remarks to a specific, reproducible version of the document. Note though that such a revision process is (much, much) better done using Pull Requests, provided the other party uses git and GitLab.

To identify versions in git, every object is uniquely identified by its hash (SHA256):

412ba291b6980ab21f912b5cdf01a13c6268d0ed

It is convenient to abbreviate the full SHA to a short version:

412ba291

Since a collision of even short hashes is essentially impossible in most use cases,

we can uniquely identify states of the project by this short SHA.

This is why commands like git show 412ba291 work (try it out; the SHA exists in this repository!).

(As a side note: GitLab picks up on those hashes automatically, as shown in

commit ccedcda0.)

So if we have this SHA available in the PDF, never again will there be confusion about versions.

The PDF will be be assignable to an exact commit.

It can look like this (in Adobe Reader, evoke file properties with CTRL + D):

Using this approach, it is hidden and will not show up in print. You can of course also add the info to the document itself, so that it will be printed. But how do we get it there?

We have a chicken-and-egg problem: if we want to insert the current SHA into the current source files, we can't. While building the current PDF, we can only know the SHA of the previous commit. But, fear not, for GitLab has you covered:

During build-time, GitLab provides environment variables.

These include things like CI_COMMIT_SHORT_SHA, which is exactly what we want.

Now, we only need to get the contents of that variable into the LaTeX source,

and finally the compiled PDF.

The LaTeX package hyperref can modify PDF metadata.

In the LaTeX preamble, we can then use, for example,

\usepackage[pdfusetitle]{hyperref}% pdfusetitle reads from \author and \title

\hypersetup{%

pdfcreator={LaTeX with hyperref (\GitRefName{}, \GitShortSHA{})},

}to get metadata like in the PDF above.

Navigate to the hyperref line in the class file to the see

current implementation.

Note that in LaTeX, you likely used \author{<author's name>} and \title{<document title>}

somewhere in the preamble to generate a title page.

hyperref's pdfusetitle option will use those values for the PDF metadata.

Lastly, pdfcreator will fill the Application field we see above.

However, \GitRefName{} and \GitShortSHA{}} need to be defined first.

This happens earlier in the preamble:

\directlua{

dofile("lib/lua/envvar_newcommands.lua")

}This runs, with the help of LuaTeX's Lua integration,

some Lua code directly in LaTeX.

Within Lua, os.getenv(<string> name) lets us retrieve environment variables, which are

then turned into macros/control sequences (\newcommand) of a given name using

token.set_macro(<string> csname, <string> content), see the LuaTeX reference

on all the included Lua functionality provided by LuaTeX, on top of regular Lua.

On the top of the project page, we can add badges. That's how GitLab calls the small, clickable buttons. For real software developers, these might display code coverage and similar things. For, well... us, they can be used as a convenient way to download the built PDF. It can look like this (center left):

A little image (svg format) can be generated using shields.io.

That only needs to be done once, and if you want to reuse the existing ones, here they are:

They have been embedded directly into the repository to not have to download them

each time.

They could also be embedded via their URL, for example

https://img.shields.io/badge/Cookbook-Download-informational.svg.

To add them to the project, go to:

Settings -> General -> Badges.

Give it a Name, enter the above file path or URL for the Badge image URL

(or do whatever you want here), and finally enter the Link.

This part is a bit tricky, since we need a dynamic URL that adapts to our path.

For this, GitLab provides variables like %{project_path}.

As such, the URL is (the hyphen in the middle is intentional):

https://collaborating.tuhh.de/%{project_path}/-/jobs/artifacts/%{default_branch}/raw/<filename>.pdf?job=build_pdfThe project_path is clear, the default_branch is just master.

It visits the job artifacts on master and gets the PDF with the supplied filename.

This filename has to be adjusted accordingly.

Note that the download is unavailable while a job is running.

To avoid this, work on a git branch and leave master alone.

Treat the PDF (or whatever it is) on master as the current stable version that only changes sometimes,

not with every commit.

For example, you can do your continuous business on a dev branch and then add a second button,

https://collaborating.tuhh.de/%{project_path}/-/jobs/artifacts/dev/raw/<filename>.pdf?job=build_pdfMany nights were lost over issues involving GitLab CI/CD, but also plain LaTeX. Here is a non-exhaustive list --- a bit like a gallery of failure --- of the most common ones. Hopefully, it spares you some despair.

-

You run into a similar error as:

! Package pgfplots Error: Sorry, the requested column number '1' in table 'dat. csv' does not exist!? Please verify you used the correct index 0 <= i < N..This can happen if you use

pgfplotstablefor plotting from tabular data, be it inline or from an outside file. If you usematlab2tikz, you might also run into the above error, since it potentially uses inline tables.In the class file, there is a line reading:

\pgfplotstableset{col sep=comma}% If ALL files/tables are comma-separated

This is a global default for all tables, assuming that they are comma-separated. The default is whitespace, which

matlab2tikzuses, hence it breaks. You can override the column separator either in the above global option, or manually for each plot:% See https://tex.stackexchange.com/a/251245/120853 \addplot3[surf] table [col sep=comma] {dat.csv};

-

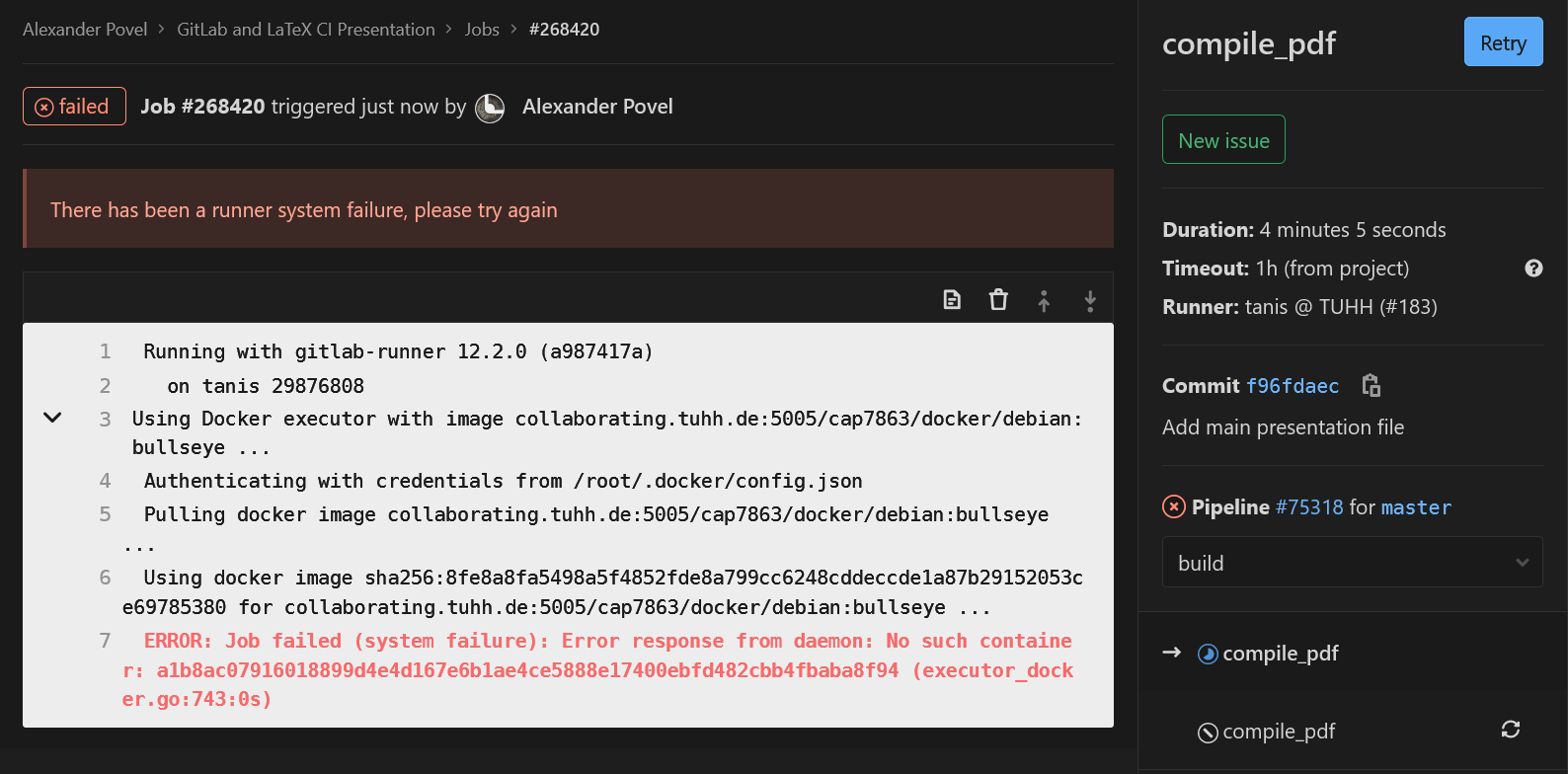

The job is working on

Pulling docker imagelink to docker imagefor a while, and finally fails withERROR: Job failed (system failure): Error response from daemon: No such container <some long container ID>

Since, after we ensured the image indeed exists, know that cannot be the case, we Retry the job from the job page's top right corner:

It should work afterwards (it never failed to restart after retrying for me). This will happen once in a while for some reason, perhaps caching. This has been an active issue for over two years now, with (at time of writing) the most recent comment within the last 24 hours. So, it is still in active discussion. It seems to have to do with caching. There does not seem to be a solution yet.

This should be fixed now (at least, ever since the fix was applied, the issue no longer occurred), see here. This relies on the

retrykeyword in GitLab CI. -

When using package

fontspec(or its derivativeunicode-math), compilation fails with! error: (type 2): cannot find file '' ! ==> Fatal error occurred, no output PDF file produced!It is possible that the font cache is corrupted after moving fonts around. For example, if previously all fonts were in a flat

./fonts/subdirectory of your document root, and then you decide to sort them into./fonts/sans/etc., the luatex cache will still point to the old ones.See here and also, similarly, here for a solution: delete the

.luaand.lucfiles of the fonts in question fromluatex-cache/generic/fonts/. For MiKTeX 2.9 on Windows 10, this was found in%USERPROFILE%\AppData\Local\MiKTeX\2.9\luatex-cache. -

When using package

pgf-spectracompilation fails withLaTeX Error: File 'spectra.data.tex' not found.For a solution, see here, where it says:

Hi

texlive/2016/texmf-dist/tex/latex/pgf-spectra/pgf-spectra.sty

ends with

\input{spectra.data.tex}

which generates a missing file error if the package is used, the data file is on ctan but it's misplaced in texlive as

texlive/2016/texmf-dist/doc/latex/pgf-spectra/spectra.data.tex

It should be in the tex tree not doc,

David

So, get

spectra.data.texfrom CTAN and place it accordingly. This can mean placing it in the project root. It would be better to put it next to the package file itself,pgf-spectra.sty, but this did not work even after refreshing the package database. This occurred on MiKTeX 2.9. TeXLive seemed fine in version 2019. -

The error is or is similar to:

! Undefined control sequence. l.52 \glsxtr@rWith an

*.auxfile mentioned in the error message as well. Here, an auxiliary file got corrupted in an unsuccessful run and simply needs to be deleted. Do this manually or usinglatexmk -c. -

Concerning

glossaries-extra:-

Using

\glssetcategoryattribute{<category>}{indexonlyfirst}{true}. For all items in<category>, it is meant to only add the very first reference to the printed glossary. If this reference is within a float, this breaks, and nothing shows up in the '##2' column.The way the document was set up, most symbols are currently affected. However, in an actual document, it is highly unlikely you will be referencing/using (with

\gls{<symbol>}) symbols the first time in floating objects. Therefore, this problem is likely not a realistic issue. -

In conjunction with

subimport: That package introduces a neat structure to have subdirectories and do nested imports of*.texfiles. But that might not be worth it, since it breaks many referencing functionalities in for example TeXStudio.More importantly, it seems to cause

glossaries-extrato no longer recognize which references have occurred. We currently callselection=allin\GlsXtrLoadResourcesto load all stuff found in the respective*.bibfile, regardless of whether it has actually been called at some point (using\gls{}etc.). This is a bit like ifbiblatexdid not recognize cite commands and we just pulled every single item in the bibliography file. Some people use gigantic*.bibfiles, shared among their projects. If suddenly every entry showed up in the printed document despite not being referenced (be it a glossary or a bibliography item), chaos would ensue.

-

These are valid not only for LaTeX files, but most text-based source files:

- For the love of God, use

UTF-8or higher for text encoding. Stop usingWindows 1252,Latinetc. Existing files can be easily updated to UTF-8 without much danger for regression (i.e., introducing errors). - Put each sentence, or even part of a sentence, and each instruction onto its own line.

This is very important to

difffiles properly, akagit diff. Generally, keep lines short. - In a similar vein, use indentation appropriately. Indent using 4 spaces. There are schools of thought that advocate two spaces, or also one tab. Ultimately, that does not really matter. 'Four spaces' just seems to generally win the fight for a common coding style, bringing us to the next point.

- Be consistent. Even if you pull your own custom stuff, at least be consistent in doing so.

This makes things predictable, the code will be easier to read, and also more easily

changed programmatically.

GNU/Linux and by extension Windows using

Windows Subsystem for Linux

has a very wide range of tools that make search, and search-and-replace, and various other

operations for plain text files easy.

The same is true for similar tools in IDEs.

However, if the text is scattered and the style was mangled and fragmented into various

sub-styles, this becomes very hard.

For example, one person might use

$<math>$for inline-LaTeX math, another the (preferred)\(<math>\)style. Suddenly, you would have to search for both versions to find all inline-math. So stay consistent. If you work on pre-existing documents, use the established style. If you change it, change it fully, and not just for newly added work.