Dependencies

- Visual Studio Build Tools 2017, including Windows SDK and Universal C Runtime.

- The

cl.execompiler andlink.exelinker in PATH.

Clone (or alternatively download) the repo.

$ git clone https://github.com/TusharRakheja/Autolang

Then navigate into the directory and from Command Prompt (not PowerShell) run:

$ vcvars64 & nmake

Autolang can be used either with a file, or interactively. The filename argument is optional.

$ .\auto.exe filename.al

The real joy of Autolang is its very math-oriented syntax. Here are some cool examples you can try.

- Containers

- Abstract Containers

- Automata

- Sources and Sinks (I/O)

- Functional Concepts

- Data as Code

- Loops and Conditionals

- Notes

Autolang has three primitve data types, int, char, and logical.

Standard 32-bit. The type keyword is int, as you've already probably seen.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare int i # Integers are initialized to 0 by default. Characters to '\0', and logicals to False.

>>> print i

0

>>> int j = 1 # A custom initialization is also possible.

>>> print j

1

>>> declare ints k, l # Using the type of the object in plural, multiple declarations can be made in one statement.

>>> print k, l # Print multiple space-separated objects using commas.

0 0Operations and Updates

Here is a brief list of examples illustrating operators and updaters that work with integers; in fact, with all primitive values in Autolang. For characters, they are basically the same. The operators (==, +, ^ etc), as noted, will implicitly cast values across them if need be. However, updaters (=, +=, ^= etc) will not.

>>> int i = 2

>>> print (1 + (3 * i)) / 7 # All the usual arithmetic operators work, but they have no order of precedence. Use parentheses.

1

>>> print i ^ 10 # The '^' signifies raising a number to an exponent (not the XOR operation).

1024

>>> let i += 2 # A simple update. One could similarly use -=, *=, ^= etc.

>>> print (i % 2) == 0 # All comparative operators are supported (<, >, <= etc).

True

>>> print |14| + |-13| # |n| is the modulus of n. Use |(n)| for an expression.

27Characters are quite similar to integers. They keyword is char. I'll illustrate the main situations in which they behave differently from integers.

Basic Syntax

They are declared and initialized like so:

>>> declare char null # All characters are initialized to '\0' by default.

>>> print null == '\0' # To define an escape character, use a backslash.

True

>>> char brace = '\}' # All braces, parentheses, and brackets also need to be preceded by the backslashes.

>>> print brace # This is to make sure the parser doesn't confuse if for a closing brace of a set or something.

}

>>> printr brace # To print a char in its 'raw' form, with quotes and all, use the printr command.

'\}'Operations and Updates

>>> print |'a'| # For characters, '|' prints the ASCII value.

97(For more, refer to section Operations and Updates under Integers)

Boolean values have the keyword logical, and the literals are represented by True and False.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare logical val # By default, logicals are initialized to False.

>>> print val

False

>>> logical comp = 1 < '1' # Custom initialization. ASCII value of '1' is used.

>>> print comp

TrueOperations and Updates

>>> print True V False # The logical OR (disjunction).

True

>>> print True & False # The logical AND (conjunction).

False

>>> print !True # Negation (a unary operator).

False

>>> logical val = (4 % 2) != 0 # To illustrate the updates.

>>> print val

False

>>> let val V= True # Semantically equivalent to `val = val V True`

>>> print val

True

>>> let val &= False # Semantically equivalent to `val = val & False`

>>> print val

False

>>> print 23 ^ False # Another example of automatic casting. Will give a one.

1(For more, refer to section Operations and Updates under Integers)

Autolang has four kinds of containers, viz sets, tuples, maps and strings.

The key data structure in Autolang is a set - a (possibly heterogeneous) collection of elements.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare set A # Declares an empty set A.

>>> print A

{}

>>> set easter = {27, 'J', 1996, A} # Initializes a set with these elements. Identifiers as well as literals allowed.

>>> print easter

{27, J, 1996, {}}

>>> printr easter # The printr command recursively prints the raw version of the elements.

{27, 'J', 1996, {}}

>>> print exprset = { 1 + 2, 3 + 4 } # The elements of a set can be expressions as well.

{3, 7}Basic Operations

>>> print {1, 2} U {1, 3} # Union of two sets.

{1, 2, 3}

>>> print {1, 2} & {1, 3} # Intersection.

{1}

>>> print {1, 2} \ {1, 3} # Exclusion.

{2}Advanced Operations

>>> set A = {1, 2, 3} x {'A', 'B'} # Cartesian Product. The result is a set of tuples.

>>> print A

{(1, A), (1, B), (2, A), (2, B), (3, A), (3, B)}

>>> print |A| # Print the cardinality of set A (an integer).

6Subset Query

>>> print {(1, 'B')} c A # Is this set a subset of A?

TrueAccess Query

In addition to the standard set operations, it is possible to access a member of a set at a specific position, using the [] operator (may also be used with tuples).

>>> print A[1] # Access the element of A at index 1.

{(1, B)}

>>> print A[(1, 3)] # Access the subset of A between [1, 3).

{(1, B), (2, A)}An element of a set accessed via the [] operator can be used exactly like you'd expect. For instance:

>>> set A = {{1, 2}, {3, 4}} # A set of sets.

>>> let A[1] \= {4} # Directly update the set at index 1 of A.

>>> print A

{{1, 2}, {3}}Membership Query

The in operator returns a logical value if the left argument is present in the right argument. Just like the access query operator, it may also be used with tuples.

>>> print ('2' in {1, {'2'}, 3}[1]) # The 'in' and '[]' operators in action.

TrueBasically a lightweight container which works just like a set, but with a somewhat limited interface. A tuple doesn't have either operators or updaters of its own, unlike U, U= for sets and V, V= for logicals.

Basic Syntax

>>> tuple A = (1, ) # A single-element tuple needs a trailing comma.

>>> print A[0]

1

>>> declare tuple entry

>>> string given = "Tushar"

>>> string family = "Rakheja"

>>> let entry = (given, family) # Identifiers can be used as elements.

>>> print entry

("Tushar", "Rakheja")

>>> print |entry| # Print the dimension of the tuple.

2The rationale behind adding tuples was to provide support for generalized ordered pairs. The idea wasn't for them to be used as set-like containers, even though the underlying implementation is much the same (for now). Hence, to write code in the spirit of Autolang, tuples should be treated as immutable.

In order to help with that, we'll introduce a new operator.

Deep Copy

The deep copy operator . is a unary operator, that makes a copy of the expression to the right of it. It's called deep copy because if the expression is a container, all elements within the container will also be copied, recursively.

>>> int A = 1 # We'll use these two elements to illustrate.

>>> int B = 2

>>> tuple shallow = (A, B) # We're making a tuple that has `A` and `B` as its elements.

>>> tuple copy_AB = (.A, .B) # We're making a tuple that has 'copies' of A and B.

>>> tuple copy_shallow = . shallow # We're making a tuple that is a deep copy of shallow.

>>> let A += 3 # This will modify the contents of `shallow`, but not those of the two `copy` tuples.

>>> print shallow # This is because the tuple `shallow` has as its elements the 'objects' that A and B identify.

(4, 2)

>>> print copy_AB # Whereas, the tuple `copy_AB` was made with copies of those objects, which were not affected by the update.

(1, 2)

>>> print copy_shallow # The tuple `copy_shallow` was a copy of `shallow` made before the update. Since the '.' operator is recursive, it made copies of the objects inside of `shallow` as well.

(1, 2)So, this is how the . operator works. If ever one needs to use something inside a tuple as an rvalue, it will be preferable to use a deep copy there as well, in order to preserve the convention of tuple immutability. It is possible, however, to access individual elements in a tuple using the [] operator, both as lvalues and rvalues.

Container for a sequence of characters.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare string null # By default strings are initialized to "".

>>> print null == ""

True

>>> string str = "\(\n\)" # Just like in the case of characters, escape sequences are identified by \.

>>> print str

(

)

>>> printr str # Raw printng.

"\(\n\)"Operations and Updates

>>> string hello = "Hello"

>>> string world = "World"

>>> print hello + " " + world # Strings can be concatenated with the + operator.

>>> string hellow = hello

>>> let hellow += " " + world # The += updater will work as expected.

>>> let hellow += '!' # One can also append characters with it.

>>> print hellow

Hello World!Strings also support the [], in, and || operator.

>>> string test = "ABCD"

>>> print test[1] # Returns the character at index 1.

B

>>> print |test| # Returns an int = the size of the string.

4

>>> print test[(1, 3)] # Returns the substring between [1, 3).

BC

>>> logical val = ('A' in test) & ("BCD" in test)

>>> print val # The 'in' op can take strings and chars both.

TrueA thing to keep in mind is that the [] operator for strings follows value semantics, unlike in the case of sets and tuples. It does not return references to characters of the string, but instead, returns new copies of those characters.

Typeof operator

typeof is a unary operator that takes in an expression, and return a string denoting it's type.

>>> print typeof 1

int

>>> printr typeof (True V False)

"logical"Containers that store mappings between two sets of elements are called maps. Their syntax is inspired by the mathematical definition of a function.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare map fog # Declare a map fog

>>> map f : {"One", "Zero"} -> {True, False} # Initialize a map with a given domain and codomain.

>>> under f : "One" -> True # `Under f, "One" goes to True.`

>>> under f : "Zero" -> False

>>> print f

{(One, True), (Zero, False)}Operations and Updates

Maps can be queried for their mappings using the [] operator, and just like regular mathematical functions, maps can be composed with each other, using the o operator (given that the domains and ranges of the arguments match appropriately).

>>> print f["One"] # Maps can be queried this way.

True

>>> map g : {1, 0} -> {"One", "Zero"}

>>> under g : 1 -> "One"

>>> under g : 0 -> "Zero"

>>> print |g| # Prints the number of mappings in the map.

2

>>> let fog = f o g # Let fog = the composition of maps f and g.

>>> print fog

{(1, True), (0, False)}

>>> let f o= g # The compose-update. Equiv. to `f = f o g`.

>>> print f[1]

TrueAutolang also supports the notion of functional powers. Maps are kind of a translation of the mathematical notion of a function as a mapping between two sets. Hence, it only makes sense that if composition is supported, powers should be too.

For instance, for a map F, F3 is equivalent to F o F o F ( i.e, F composed with itself twice).

>>> declare map fcube # Will be used for illustration.

>>> map f : {1, 2, 3} -> {1, 2, 3}

>>> under f : 1 -> 2

>>> under f : 2 -> 3

>>> under f : 3 -> 1

>>> print f

{(1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 1)}

>>> let fcube = f ^ 3 # `fcube` is the map `f` composed with itself once.

>>> print fcube

{(1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3)}

>>> let f ^= 2 # The power update also works on maps.

>>> print f

{(1, 3), (2, 1), (3, 2)} Maps have many uses. For instance, they can be used to implement associative arrays. See the Examples directory for an example.

Autolang has two abstract containers, sets and maps. Abstract containers are preceded by the abstract keyword during declaration/initialization.

One very powerful concept Autolang supports is that of an abstract set. Unlike a normal set, an abstract set does not have fixed members, but rather, an input format and a membership criteria.

The input format describes the structure of a generic element in/query on the set. The membership criteria is supposed to be a logical expression, which is evaluated for every query on the set when needed.

Basic Syntax

For example, let us say we want to make an abstract set that contains sets that:

- Have strictly two elements, and

- The product of the two elements is even.

>>> declare abstract set EvenP # Abstract sets are declared just like normal sets, but with the abstract keyword.

>>> let EvenP = { {a, b} | ((a * b) % 2) == 0 } # This is an abstract set literal.

>>> print {1, 2} in EvenP

True

>>> print {1, 3} in EvenP

False

>>> print EvenP

{ {a, b} | ((a * b) % 2) == 0 }The input format can be arbitrarily complex or deep, but must not contain any operators. Also, a placeholder will override an identifier if they have the same name.

>>> int l = 4000

>>> abstract set Test = { l | l < 2000 }

>>> print 3 in Test # The local placeholder 'l' will override the int 'l'.

TrueThe format is also strictly binding, in that the program will raise an error (or sometimes, crash! *gasp*) if the input doesn't match.

If you get creative, there's a lot that suddenly became possible with abstract sets. For instance.

>>> set A = {1, 2, 3} # Autolang also supports the notion of 'abstract' sets.

>>> abstract set PowA = { elem | elem c A } # Define the PowA as the power set of A.

>>> print {1, 3} in PowA

True

>>> print {1, 4} in PowA

FalseOperations and Updates

Most set operations will also work with abstract sets, except the [] operator (since an abstract set can be potentially uncountably infinite in size). However, an operation between an abstract set and a normal set is not possible (for now), except a subset operation (which, (un)interestingly, cannot be performed on two abstract sets).

>>> abstract set Inter = PowA & EvenP # Take the intersection of two abstract sets.

>>> print {1, 2} in Inter

True

>>> print {1, 3} in Inter

False

>>> print {{1, 2}, {2, 3}} c Inter # A subset op between a normal and an abstract set.

TrueOf course, one can make new abstract sets by taking unions, exclusions, and cartesian products of two abstract sets as well, as well as perform the corresponding updates.

The operand sets can have the same placeholders too, Autolang takes care of that by modifying the placeholders.

Some built-in abstract sets

If you take the keyword representing a data type and capitalize the first letter (ASet and AMap for abstract sets and maps resepectively), you get an abstract set containing all objects with that data type. The All abstract set will return True for every membership query. These are useful for restricting the domains and codomains/ranges of abstract maps.

Interesting: The abstract set ASet is an abstract set containing all abstract sets. So, it contains itself!

>>> print ASet in ASet

TrueWe have established that certain objects can contain themselves. So what if we define a set as follows:

>>> abstract set S = { obj | ! (obj in obj) } S contains all objects that do not contain themselves. So, ASet would not be in S. But,

is S in S? Turns out, S in S ↔ ! (S in S).

This is called Russell's Paradox, and the expression S in S results in a stack overflow in Autolang.

Just like abstract sets, abstract maps do not store mappings, but rather, have an input format and a mapping scheme, which generate the image for an incoming pre-image query.

Basic Syntax

>>> declare abstract map add # Abstract maps can be declared the same way as normal maps, with the 'abstract' keyword.

>>> under add : (a, b) -> a + b # Take in a tuple of two objects, add them up.

>>> print add[(1, 2)]

3

>>> print add[("A", "B")]

ABThe mapping scheme can include a recursive call to the map itself.

>>> abstract map fact : Int -> Int # The domain and codomain of abstract maps have to be abstract sets.

>>> under fact : n -> (n < 2) ? 1 : (n * fact[n - 1])

>>> print fact[5]

120We used a conditional operator ?: in the fact map, which is the only ternary operator in Autolang. Abstract maps can be composed with the o operator and the o= updater too, but since the subset operation cannot be performed on their domains and codomains, any composition between two abstract maps is possible. However, a composition between an abstract and a normal map is not possible (for now).

It's a good time to remember that abstract maps are also objects, just like regular maps, and hence can be part of sets and tuples.

Operations and Updates

>>> declare abstract maps square, octa # If the domain and range are not specified, no restriction on input/output.

>>> set pmaps = { square, octa } # Make a set of abstract maps.

>>> under pmaps[0] : n -> n ^ 2 # Assign a mapping scheme to pmaps[0], which is the map `square`.

>>> print pmaps[0][3] # Print the square of 3.

9

>>> let pmaps[1] = pmaps[0] ^ 3 # Let the map `octa` be the cube of the map `square`.

>>> print octa[2] # Query the abstract map.

256Automata are the inspiration behind Autolang - both, the name as well as the language itself (at least the initial decision to make it). For now, Autolang supports only Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA), but NFA will be coming soon. (and then some more!)

The keyword for DFA is auto. Since (deterministic finite) automata are formally describes as quintuples, the syntax reflects that.

Basic Syntax

Typically before initializing an automaton, a lot of work needs to be done. An automaton M = (S, Σ, s0, δ, A), where S is the set of states, Σ is the input alphabet, s0 is the starting state, δ is the transition function, and A is the set of accepting states.

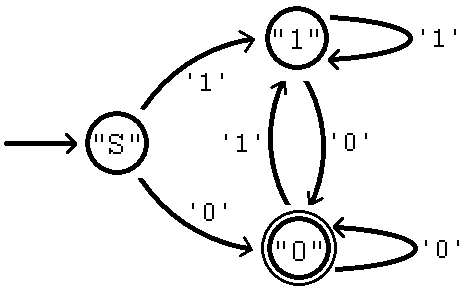

Let's write code to implement this automaton.

>>> declare auto binall # We'll use it later.

>>> set states = { "S", "1", "0" } # The set of states for the automaton.

>>> set sigma = { '1', '0' } # The input alphabet.

>>> map delta : states x sigma -> states # The transition map for the automaton.

>>> under delta : ("S", '0') -> "0" # The mappings are such that ...

>>> under delta : ("S", '1') -> "1" # ... the resulting automaton ...

>>> under delta : ("0", '0') -> "0" # ... will accept all strings ...

>>> under delta : ("0", '1') -> "1" # ... that are binary representations ...

>>> under delta : ("1", '0') -> "0" # ... of even integers, and ...

>>> under delta : ("1", '1') -> "1" # ... will reject all others.

>>> auto bineven = (states, sigma, states[0], delta, states[(2, 3)]) Operators and Updates

Automata can be queried using the [] operator. Standard set operations, like U, & and \ can also be used to generate automata that accept strings accepted by either, strictly both, or strictly one of the two automata.

>>> print bineven["100"] # Automata can be queried using the [] operator.

True

>>> print bineven["101"] # If a string is accepted, the result is True. Else False.

False

>>> auto binodd = (states, sigma, states[0], delta, states[(1, 2)])

>>> let binall = bineven U binodd # Let binall accept L(bineven) U L(binodd).

>>> print binall["100"]

True

>>> print binall["101"]

TrueThe corresponding updates will also work, but it's hard to imagine when they'll ever be useful.

Languages of Automata

The language of an automaton M, L(M), is defined as the set of all strings accepted by M. A simple abstract set ought to be enough to implement this idea.

>>> abstract set l_even = { elem | bineven[elem] } # Will evaluate to true for strings accepted by bineven.

>>> print "100" in l_even

True

>>> print "101" in l_even

FalseData is to computer science, what energy is to physics. Autolang calls all sources of input sources, and all those of output sinks (of data).

A file source is a 2-tuple, where the first element is the path of the file to be treated as a source, and the second element is the delimiter for strings.

Basic Syntax: Source

For example, consider a file data.txt:

1 minute.

{4, 'l'}

(5, 'l')

True | story.

Now consider this piece of code that reads it. source is the type-specifying keyword.

>>> source data = ("data.txt", '\n') # (filepath, delimiter)

>>> print data # Prints all the file's contents.

1 minute.

{4, 'l'}

(5, 'l')

True | story.Operators and Updates: Source

Printing out the source exhausts it. So we need to reset it before trying to read data.

>>> print !data # Prints True if the source is in an unreadable state.

True

>>> let data += 0 # The += and -= operators offset the source by the specified number of bytes, and reset it if needed.

>>> print |data| # The source should now ready to read, from the very top. So the number of bytes we've already is 0.

0

>>> int readone <- data # Variables can be initialized directly with data coming from a source, using the `<-` updater.

>>> print readone # The delimiter is not used when reading ints and chars.

1

>>> let data[1] = '.' # The delimiter is a part of the source's tuple and can be accessed intuitively.

>>> declare string sample # To read data into pre-existing variables,

>>> get sample <- data # the '<-' updater can be used with the 'get' keyword.

>>> print sample # The delimiter is not read into the string, and the source moves past it.

minute

>>> let data -= |sample| # To re-read some data we just read, we can use the -= update to send the source back by some amount.

>>> get sample <- data # And then simply read it again.

>>> print sample

minute

>>> let data += 1 # We can just skip/move past the '\n' in the file after '.'.

>>> let data[1] = '\n' # The next data we read will be read till a newline.

>>> set newsample <- data # Sets can also be initialized with data coming in from a stream.

>>> print newsample

{4, l}

>>> tuple another <- data # Tuples also, obviously.

>>> print another

(5, l)

>>> let data[1] = '|' # Even though logicals 'can' be read in from sources, it's not advised. At all.

>>> logical true <- True # If you must, set the delimiter to something you're sure will give a clean literal.

>>> print true # I suggest reading integers instead of logicals and casting.

True

>>> print |data| # Phew, we've read in 65 bytes of data!

65

>>> quit # Quitting is advisable. If you exit your terminal directly, the next time you source this file, it'll have weird bits. You'll need to reset it. Now, what about writing to a file? We can do that with a sink. A sink has a much simpler interface, no new updaters. It's a 3-tuple - The first element is the filepath. The second element is True if the existing data in the file needs to be preserved, and False otherwise. The third element is True if the objects to be written to the file will be in their 'raw' form, and False otherwise.

Basic Syntax, Operators and Updates: Sink

>>> sink data = ("data.txt", True, False) # (filepath, append?, raw print?)

>>> string putdata = "\nSee?" # We'll append this string to the file.

>>> let data += putdata # Print the string in it's processed format.

>>> let data[2] = True # Set the raw flag to True.

>>> let data += putdata # Now the string will be written in it's raw format.

>>> quit # And that's it! Sinks offer only this interfact for now.After this, the file will look like this:

1 minute.

{4, 'l'}

(5, 'l')

True | story.

See?"\nSee?"

NOTE: Please do NOT make deep copies of sources and sinks. It won't work the way you expect, but it will work enough that your program won't crash right away. Not advised!

You've seen how the print and printr commands work. That's basically how console is used as a sink. Nothing more to the interface!

However, console sourcing is a new thing we haven't talked about. In interactive mode it's obviously not needed. But if you're interpreting an Autolang source file, here's how you should use console sourcing.

Strings are not sources (no mutual = updates possible), but they can be used as sources.

Basic Syntax

>>> string num = "123"

>>> int getnum <- num

>>> print getnum

123

>>> char getch <- num # Semantically equivalent to char getch = num[0]

>>> print getch

1

>>> logical g1 <- num # True iff the source string 'contains' "True".

>>> print g1

FalseThough Autolang is not pure functional language, it does support a variety of functional concepts.

Lambda expressions (λs) in Autolang are denoted with the :: symbol. Their syntax comprises of an input format and a mapping scheme, just like an abstract map. In fact, internally, they are treated like abstract map 'literals', if you will.

>>> print :: (a, b) -> a + b ::[(9, 9)]

18Using the let keyword, we can bind λs to existing abstract map identifiers.

>>> declare abstract map add

>>> let add = :: (a, b) -> a + b ::

>>> print add[("Brooklyn", " Nine-Nine")]

>>> Brooklyn Nine-NineHigher-order functions are functions that can take one or more functions as arguments.

As a demonstration of Autolang's functional capabilities, I've implemented two higher-order functions typically found in functional languages, namely map (as apply), and reduce (as fold). apply takes a map and applies it to every member of a set, and fold takes a binary operator-map and 'folds' or 'reduces' all the set members under that operator.

>>> print fold[(add, {1, 2, 3, 4})] # computes 1 + 2 + 3 + 4.

10

>>> print fold[(mult, {1, 2, 3, 4})] # computes 1 * 2 * 3 * 4.

24

>>> print apply[(:: n -> n ^ 2 ::, {1, 2, 3, 4})] # A λ in place of a map will do just fine.

{1, 4, 9, 16}Their implementation has been left as an ... nah, I wouldn't do that. I hate it. Really.

"No, I don't need you to tell me what IS and what isn't an exercise for me, you condescending narcissist. Fuck you!"

-Rex, to every cocky mathematician in the world.

>>> under apply : (am, s) -> (|s| == 1) ? { am[s[0]] } : ({ am[s[0]] } U apply[(am, s[(1, |s|)])])

>>> under fold : (am, s) -> (|s| == 1) ? (s[0]) : (am[(s[0], fold[(am, s[(1, |s|)])])])They do come built-in with the interpreter though, so you won't need to write them again. Another criteria for higher-order functions is sometimes said to be that they return a function. That's not a problem, since that can be done.

>>> declare abstract map binop

>>> under binop : name -> (name == "mult") ? mult : ::(a, b) -> a + b::

>>> print binop["mult"][(3, 3)]

9

>>> print binop["dflt"][(3, 3)] # A lambda expression can be returned as well.

6This one is more subtle and kind of indirect. It is possible to write purely pure functions (maps) in Autolang, if you:

-

Only use literals or immutable copies with the domain and codomain.

This means writing

f : {1, 2} -> {3, 4}or.A -> .BoverA -> B. This way, the domain and codomain offwill be unaffected by any changes that happen to A or B over the course of the program, or -

Never use the

letandgetkeywords with the identifiers associated with these maps (and if the identifier is a map, noundereither).Writing

s -> s U .Ain place ofs -> s U Awould be ineffective in ensuring the same result for the sames, since it will simply make a deep copy of whatever A is at the time of the call, not at the time of definition.

As such, Autolang makes a distinction between 'operators' and 'updaters'. Operators by themselves cannot change data, only create it. The operands are not affected, so an operator applied to the same operands will always give the same result. By extension, a map using only operators will always give the same result with the same arguments (referential transparency). To fully realize this, though, the two conditions above must be met.

In fact, as such, all maps and abstract maps are half-pure by nature, in that they have no side-effects. What I mean by that is, the computation of a mapping operation, can never change any data by itself. Because updaters (=, +=, <- etc) are not allowed in a mapping scheme. They must, invariably, occur with the let or get keyword, if they are to change data (= and <- can occur with initializations too, but they aren't changing data then. They are creating it).

So, as long as the two conditions stated above are met, the map will be pure. It will be referentially transparent, and have no side-effects.

Some entities in Autolang have a way to internally call Autolang's expression parser. You guessed it, Abstract Sets and Abstract Maps. Along with sourcing, this allows us to create abstract maps and sets at runtime.

Let us say a file unpack.txt has this data.

# unpack : Unpacks tuples of the form (a, (b, c)) into (a, b, c).

(e, (f, g)) -> (e, f, g);

# unpackall : From a set of tuples of the form (a, (b, c)), return a set of (a, b, c).

s -> (|s| == 1) ? { unpack[s[0]] } : ({ unpack[s[0]] } U unpackall[s[(1, |s|)]]);

Clearly, the file contains mapping schemes for abstract maps. We can use these to make maps in Autolang. Here's how.

>>> source maps = ("unpack.txt", '\n') # Open file.

>>> string junk <- maps # Eat comments and blank lines.

>>> let maps[1] = ';' # Now it's time to read a scheme.

>>> abstract map unpack <- maps # Make an abstract map using the scheme.

>>> let maps[1] = '\n' # Time to read more junk.

>>> get junk <- maps # Eat the '\n' after the previous ';'

>>> get junk <- maps # Eat the blank line.

>>> get junk <- maps # Eat the comment.

>>> let maps[1] = ';' # Time to read another scheme.

>>> abstract map unpackall <- maps # Make the map.

>>> print unpack[(1, (2, 3))] # Time to test, yay!

(1, 2, 3)

>>> print unpackall[{1, 2} x {'A', 'B'} x {True}]

{(1, A, True), (1, B, True), (2, A, True), (2, B, True)}Interesting: Of course, the source can be console too! Which means, effectively, a client running an Autolang program can also write parts of the program, at run-time.

To see an example of how the while loop (the only looping construct in the language, right now) and the if statements work, check Examples/Example7.al out. A language specification is coming soon.

The while loop doesn't work in interactive mode.

Operators in Autolang are always right-associative by default. There is no concept of operator precedence currently. Hence, parentheses are important to get the results you need.

More generally, a thing to keep in mind is that though Autolang tries to approximate mathematical notation wherever possible, certain expressions may be tricky. For instance:

>>> set P = {1, 2} x {'a', 'b'} x {True} # We have tuples of the form (e, (f, g)), not (e, f, g) as expected.

>>> print P

{(1, ('a', True)), (1, ('b', True)), (2, ('a', True)), (2, ('b', True))}

>>> print |(P[0])| # Will not print 3, but 2.

2Depending on your moral values and whether or not you believe there is any justice in the world, this may or may not have been what you expected. But for now, this is the result.

We can adjust this particular result using the unpack map mentioned in Data as Code. Likewise, we may have to come up with such 'hacks' every now and then.

Autolang is imperfect. The parser is brittle, there are memory leaks etc. But perfection is the goal. And perfection, is a journey unto itself.

-

Lexical scoping.

-

Support for graphics.

-

Support for modularity.

-

Abstract Maps.

-

λ Expressions.

-

Abstract Sets.

-

Automatic memory management.

Copyright (c) 2016 Tushar Rakheja (The MIT License)