{{|>}}

Creators:

Marlen Fischer, Juliane Röder, Johannes Signer, Daniel Tschink, Tanja Weibulat, Ortrun Brand.

For more details about NFDI4Biodiversity and research data management for biodiversity data, visit www.nfdi4biodiversity.org.

{{|>}}

How to use this course

This is a LiaScript course. To follow the course in its intended format, please follow this link!

Only if you use the link, you will be able use all features of this course:

{{1}}

After each chapter, you can test your knowledge with questions. These questions only work in the LiaScript version, not in simple Markdown.

{{2}}

You can listen to the text by clicking on the little PLAY button on top of each page. Please note that this feature is used as commentary, this is not a tool to increase accessibility.

{{3}}

You can automatically translate the course with one click. However, please be aware that any automatic translation may contain mistakes and mistranslations of terms and concepts.

{{4}}

Please note that if you want to listen to a translation of the text, you should change the narrator voice in the html header in the raw version of this file.

For more details on the Markdown dialect LiaScript, see the LiaScript documentation.

{{|>}}

The NFDI4Biodiversity Self-Study Unit provides in-depth knowledge for both students and researchers specializing in biodiversity and environmental sciences. This course is based on the online course Selbstlerneinheit Forschungsdatenmanagement - eine Online-Einführung (HeFDI Data Learning Materials) of the Hessian Research Data Infrastructures (HeFDI). Developed in collaboration between several partners within NFDI4Biodiversity, this course offers essential domain-specific knowledge in research data management.

-

Prerequisites: No previous knowledge is required for this module. The chapters build on each other thematically, but can also be worked through individually. If information from other chapters is needed, they are linked.

-

Target audience: Master and PhD students and researchers in the field of biology and environmental sciences, especially those working with biodiversity data, who are looking for a first introduction to research data management.

-

Learning objectives: After completing this unit you will be able to understand the content and purpose of research data management and apply it in the field of biology. Learning objectives are given at the beginning of each chapter.

This course will be updated regularly, responding to feedback from the community for continuous improvement. For inquiries or additional information, please feel free to reach out to us by opening an issue or via our contact form: NFDI4Biodiversity Contact.

{{|>}}

- December 14, 2023; Version 1.0.0: https://zenodo.org/records/10377868

- December 22, 2023; Version 1.1.0: https://ilias.uni-marburg.de/goto.php?target=pg_443261_3276691&client_id=UNIMR

- June 6, 2024; Version 1.2.0: https://github.com/NFDI4Biodiversity/nfdi4biodiversity-sle/

{{|>}}

Biodiversity data encompass a vast and interdisciplinary collection of information, spanning all living species and the entire spectrum of life that has ever existed. This remarkable diversity within biodiversity data makes it a highly heterogeneous field. These datasets range from laboratory-generated data, such as results from chemical assays, biological tests, and DNA sequencing, to taxonomic records, as well as spatial and temporal data collected during field experiments, and comprehensive insights into entire ecosystems123 . Furthermore, biodiversity data extend their reach into time, including data collected from the distant past, like fossils, and continue into the present while even venturing into predictive models of the future. The complexity of biodiversity data doesn't stop there; these datasets manifest in various formats, including images, photographs, sounds, sensor data, and more. The confluence of this diversity, alongside the increasing automation processes and digitalization of data acquisition, has resulted in a deluge of heterogeneous data, necessitating progressively complex organisation, coordination, and analysis methods.

To address these challenges, Germany has established the National Research Data Infrastructure (NFDI), a pivotal initiative. Within this framework, the consortium "NFDI4Biodiversity" plays a central role. This collaborative effort brings together experts and resources to develop innovative strategies and tools for managing, coordinating, and extracting meaningful insights from the wealth of biodiversity data available today. These efforts are essential in supporting research and conservation endeavours in this field.

In the ever-evolving realms of ecology and environmental science, data play a pivotal role for generating new knowledge. From collecting data in the field to conducting experiments in the lab, researchers generate vast amounts of data. This data holds the key to understanding our natural world, from the intricate ecosystems that surround us to the impact of human activities on the environment. However, the value of this data is fully realised only when it is properly managed, organised, and shared, according to the FAIR4 and CARE-principles5. This self-learning unit is designed to empower you with the knowledge and skills you need to learn independently and effectively. Throughout this document, we will explore topics such as data collection best practices, data organisation and documentation, data storage and security, ethical considerations, and the importance of data sharing and collaboration in advancing ecological and environmental research. Whether you are a seasoned researcher looking to enhance your data management practices or a student taking your first steps into this exciting domain, you'll find valuable insights and practical guidance here, to promote data diversity for biodiversity.

As you progress through this unit, you'll become proficient in managing data effectively and contribute to the advancement of ecological and environmental science by ensuring that your research data is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. These skills are not only valuable for your work but also for the broader scientific community and society as a whole. Ecology and environmental science rely heavily on data to understand the natural world and address environmental challenges - data diversity for biodiversity.

{{|>}}

After completing this chapter, you will be able to...

{{1}}

...explain the relevance of research data management for biodiversity data

{{2}}

...name the four FAIR principles

{{3}}

...contextualise how biodiversity research may raise ethical concerns related to indigenous data

{{|>}}

Collecting biodiversity data takes a lot of energy and resources. This makes biodiversity data not only valuable for the scientist who collected it, but also to support further research and to inform policy on conservation, natural resources, land use, agriculture and more12. It is important to create a maximum output of this valuable data to protect nature, wildlife and endangered species, to prevent overfishing and extinctions as a way to counteract the climate crisis and biodiversity crisis3. Thus, biodiversity data need to be carefully handled, preserved, and shared, by making them Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR)4, and considering CARE-Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics)5.

To put good research practice6 and the FAIR principles into practice effective research data management (RDM) is needed. This requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses the planning, collection, storage, analysis, and collaborative sharing of diverse biodiversity data through a well-structured and coordinated research data management strategy7. For research in the biodiversity field, research data management is even more important as non-repeatability and the need to rely on old data, e.g. for trend analysis, is of utmost relevance.

!?This video by GFBio (2020) explains the challenges and solutions of dealing with heterogeneous data.

{{|>}}

The FAIR principles play a pivotal role in Research Data Management, emphasising the broad and diverse utilisation of research data while striving to minimise redundant research efforts. Consequently, research data should remain accessible without undue restrictions for an extended duration. This applies to the use of research data collected by the researchers themselves, but also to research data that researchers make available to each other.

The FAIR principles were developed in 2014 in a workshop at the Lorentz Center in the Netherlands and published for the first time in March 2016 in the journal Scientific Data1.

Data has to adhere to certain properties to be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable, for example machine-readability, being deposited in a trusted repository etc. The FAIR principles have been significantly refined recently2; in addition, tools have been developed to evaluate your data according to FAIR3. Ultimately, the entire research data management is geared towards fulfilling these concrete verge requirements of the FAIR principles.

{{|>}}

The CARE principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics), an addition to the FAIR principles, were introduced by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) in 2019 to address ethical concerns related to indigenous data1. They emphasise the rights of Indigenous Peoples in relation to their data, including information about their language, customs, and territories. It is true that the application of the CARE principles in Germany is still in its infancy. The Government has established the so called 3-way-strategy to provide for access, transparency and cooperation with regard to artefacts of indigenous provenance2. At the same time, they are certainly relevant for biodiversity data. For example, specimens from natural history museums have sometimes been acquired in such a way that they might contradict the CARE principles. The process of coming to terms with these relationships is just beginning and will certainly become more relevant to the biodiversity community in the future. These CARE Principles collectively aim to promote the responsible and ethical use of indigenous data, safeguarding the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples.

{{|>}}

The data life cycle (DLC) is a conceptual tool which helps to understand the different steps that data follow from data generation to knowledge creation and specifically focuses on the role of data. It strongly suggests that a professional approach to research data management involves more than just collection and analysis, but begins with detailed planning. In order to cope with the heterogeneity of biological datasets, data users, and data producers, a large variety of DLC´s are commonly used within the community. DLC´s often include between 5 and 10 steps, depending on the institution and respective research mission. However, the message and content are quite similar across DLC´s and disciplines. All DLCs share the commonality of adhering to the FAIR principles at each individual step. The differentiation between research domains relates to specific tools and services that are used within the respective community. Figure 2 displays the exemplary DLC RDM-Kit developed by a diverse community of experts and educators spanning various disciplines within the life sciences. The RDM-Kit is a suitable DLC for introducing RDM to a wider audience. The seven phases of a data cycle according to the RDM-Kit are planning, collecting, processing, analysing, preserving, sharing and reusing; an unlimited number of subsequent cycles can follow. Each step of the DLC contains further explanations and specifications in order to cope with the challenges in biodiversity research. Ideally, the FAIR principles should be considered throughout the life cycle of research data. However, the realisation might vary depending on the type of conducted research, the type of collected data and the type of researchers. Here, we focus on the steps that are specifically important for researchers, which work with biodiversity and environmental data.

As a researcher, it is worthwhile to always consider all phases when making decisions and to find out at an early stage which tools and options are available to optimise your practice in dealing with research data. It starts with the planning, then the data is collected, processed and analysed. The life cycle continues with the preservation and sharing of data, until it re-enters the process by data reuse.

!?This video by the Ghent University Data Stewards (2020) explains the research data lifecycle.

{{|>}}

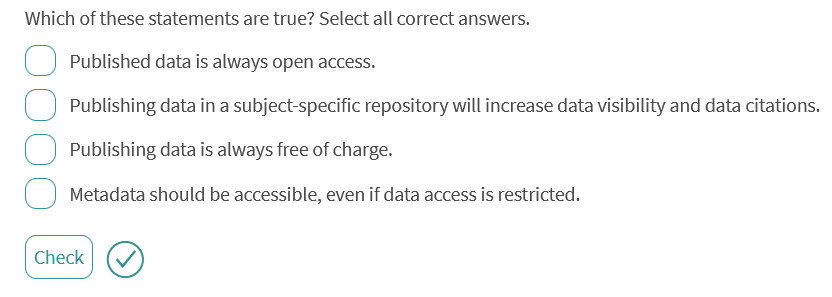

Which of the following statements is a goal of research data management? Choose the correct answer.

- [( )] Reducing the amount of research data

- [( )] Preventing active re-use of one's own research data by other researchers

- [( )] Making any research data available to all without technical restrictions

- [(X)] Minimising data loss

Correct! Minimising data loss is a goal of data security, which aims at the general protection of data and belongs to the area of data organisation. Data security doesn’t only include measures on the digital level (e.g. using anti-virus programmes or regular backups), but also on the analogue level (e.g. storing data media with very important data in fireproof boxes).

What is not part of this unit? Choose the correct answer.

- [( )] Principles to make data findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable

- [( )] Contents of a data management plan

- [(X)] Legally binding information on your research data

- [( )] Metadata and the use of metadata standards

Correct! No trained lawyers or research data officers were involved in the creation of this self-study unit, which is why legally binding information on research data cannot be given. It is merely information on the topic of “research data and law”, but it reflects common practice in research data management and is also taught by lawyers. If you need legally binding information, you should contact the legal department or/and the data protection officer of your institution.

Select the correct abbreviations.

- [[DLC] (ELN) (GBIF) (ROR) (NFDI) [FAIR] (EOSC)]

- [ (X) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ] Data Life Cycle

- [ ( ) (X) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ] Electronic Laboratory Notebook

- [ ( ) ( ) (X) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ] Global Biodiversity Information Facility

- [ ( ) ( ) ( ) (X) ( ) ( ) ( ) ] Research Organisation Registry

- [ ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) (X) ( ) ( ) ] Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur

- [ ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) (X) ( ) ] Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Re-usable

- [ ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) (X) ] European Open Science Cloud

{{|>}}

Let's have a look at the first step in the data life cycle: planning is essential for good results. This requires careful consideration, consultation, and research. A data management plan helps to organise and define the key issues.

After completing this chapter, you will be able to...

{{1}}

...define the key aspects of your planning process

{{2}}

...decide how to structure your data management plan

{{3}}

...find a suitable tool to help you create a data management plan

{{|>}}

When it comes to research data management, many research funders already require a so-called data management plan (DMP) when the application is submitted. However, even without explicit requirements, it is beneficial to document in advance exactly how the data are to be handled. This creates commitment and uniformity (especially in projects with several participants or partners) and can serve as a reference, a checklist, and as documentation.

In general, the following aspects could be relevant for planning:

- Determine study design

- Assemble project team and clarify roles

- Set up a schedule

- Plan data management (formats, storage locations, file naming, collaborative platforms, etc.)

- Review existing literature and data

- Reuse of existing data, if applicable and accessible

- Clarify authorship and data ownership

- Coordinate access possibilities and conditions

Creating a DMP for your research project is the initial step of the data life cycle and the starting point of your research data management12.

{{|>}}

In your data management plan (DMP), you define the strategy on how to manage your data and documentation during the whole project.

A DMP is a comprehensive document that outlines the activities to be performed and their implementation during all phases of the data life cycle to ensure the data remain accessible, usable, and comprehensible (understandable). Of course, this also includes basic information such as the project name, third-party funders, project partners, among others.

The DMP thus records how the research data are handled during and after the research project. To create a substantial DMP, it is necessary to systematically address topics such as data management, metadata (structured data that describe the data), data retention and data analysis. It makes sense to create the DMP before starting the data collection because it forms the basis for decisions concerning data storage, backup, and processing, among other aspects. Nevertheless, a DMP is not a static document, but rather a dynamic document that is constantly updated and provides assistance throughout your whole project.

The DMP contains general information about the project and the way of documentation, descriptions of the used and collected data, used metadata, and ontologies (Figure 3). Furthermore, it includes information about data storage, data security, and preservation during and after the project, sharing of the data, and publication. The responsibilities, costs, and resources needed are listed as well as information about ethical and legal issues1. This is also important to meet the Nagoya protocol needs, e.g. permits for collecting samples.

!?This video by GFBio (2020) explains why you should create a DMP at the beginning of your project.

{{|>}}

The DMP contains information about the data, the data format, how the data are handled and how the data are to be interpreted. Recently, a DFG checklist has provided further guidance on these aspects1. To decide which aspects should be included, the following questions can be helpful:

- What data are created?

- How and when do you collect the data? And, which legal regulations are relevant for your research project? For example, are permits required for collecting samples, is the Nagoya protocol relevant and permits to import or export samples are needed?

- How do you process the data?

- What format do you have for data storage and why?

- Do you use file naming standards?

- How do you ensure the quality of the data? This refers to the collection as well as to the analysis and processing

- Do you use existing data? If so, where does it come from? How will existing and newly collected data be combined and what is the relationship between them?

- Who is responsible for data management?

- Are there any obligations, e.g. by third-party funding bodies or other institutions, regarding the sharing of the data created? (legal requirements also play a role here)

- How will the research data be shared? From when on, and for how long will it be available?

- How will the research data and objects be archived and is it mandatory (e.g. DFG requires storing data)? (When you plan to add your data and objects to a collection, curators should be already contacted during the planning phase, also keep the storage regulations for physical objects in mind).

- What costs arise for the RDM (these include e.g. personnel costs, hardware and software costs, possible costs for a repository) and how are these costs covered?

- What ethical and data protection issues need to be taken into account?

- Is it necessary for political, commercial, or patent reasons to make the research data accessible only after a certain blocking period (Embargo)?

- How will the data be used in the future?

- In what way should the data be cited? Can the data be made unambiguous and permanently traceable using a persistent identifier?

There are different DMP templates available which you can use. Before writing your DMP check with your funding agency or institution whether a specific DMP template is required. If not, here are two examples:

- GFBio services provide expert guidance and assistance on standards and suitable archives. You can use the GFBio DMP Tool online, or refer to the GFBio Model Data Management Plan (DMP) for basic structuring.

- The HU Berlin offers standardised DMP templates for different funders (Horizon 2020, BMBF, DFG, Volkswagenstiftung).

{{|>}}

A DMP will make your project more efficient, simplify your own reuse of the data, and help you make your data findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable, also called FAIR. It will help you to plan the costs of equipment and resources, identify problems and find solutions at an early stage. It will also clarify responsibilities and roles in the project team and facilitate data preservation, sharing and reuse. It is good research practice to write a data management plan and thus take care of your research data. Currently, it is frequently a requirement by research organisations and funders12.

Overall, the DMP will save you time later on in the publishing process and prevents data loss - the main winner of creating a DMP is you! If you consider in advance how the data should be processed, stored, and filed, you probably won't have to reorganise your data. If, for example, it is already clear during data collection how the data is to be archived later, it can be formatted and stored right away in such a way that the transfer to the later archive is as simple as possible. Some domain-specific data centers strongly encourage you to contact them early on in a project to determine concrete requirements for taking on your data. There is a strong benefit of going towards FAIRness with a DMP: A DMP will allow you to gather in one document how to deal with the heterogeneous biodiversity data from collections, research, etc. and will serve as a model for understanding this information and disseminating it.

{{|>}}

There is now a whole range of tools to support researchers during each step of the data lifecycle. Data Management Planning tools, for example, facilitate the creation of data management plans either using text modules (RDMO Organiser on GitHub, RDMO University Marburg) or one is guided through a catalogue of questions. There are usually different templates for different funders and purposes that often provide web-based DMP tools that help you to draft your own suitable DMP1. GFBio, for instance, offers a Data Management Plan Tool (GFBio DMP-Tool, DMP Tool, DMP online) that is tailored to create customised DMPs according to DFG guidelines based on the requirements of biodiversity, ecological, and environmental projects. Further, GFBio offers professional support. Thus, your DMP will be cross-checked by experts in the field.

Furthermore, there are data management tools which support data management during the active project phase. Data management tools are software applications or platforms designed to efficiently collect, store, organise, process, and analyse data, but they often have to be set up and hosted by your institution or project partners. Here's a brief explanation of key aspects of data management tools:

Data Collection: Data management tools often provide capabilities to collect data from various sources, including databases, sensors, forms, and external APIs. They streamline the process of gathering information and ensure data is standardised for consistency.

Data Storage: These tools often provide storage solutions, such as databases, data warehouses, or cloud-based storage. Data is typically organised into structured formats for easy retrieval.

Data Organisation: Data management tools allow users to categorise and label data, assign metadata (information about the data), and create data dictionaries to maintain order and accessibility.

Data Processing: Many tools include data transformation and processing features for tasks like cleaning, aggregating, and merging data. This ensures data is accurate and ready for analysis.

Data Analysis: Advanced data management tools often integrate with analytics and visualisation tools, enabling users to derive insights, generate reports, and make data-driven decisions.

Data Security: Security features like encryption, access control, and authentication are critical to protect sensitive data from unauthorised access or breaches.

Data Backup and Recovery: Reliable tools include data backup and recovery mechanisms to prevent data loss due to accidents or system failures.

Data Compliance: Data management tools often assist in compliance with data regulations by providing features for data anonymization, audit trails, and consent management.

Data Collaboration: Some tools offer collaboration features, allowing teams to work together on data-related tasks, share insights, and maintain version control.

Data Governance: Data governance features help organisations establish policies, standards, and procedures for managing data, ensuring data quality, and maintaining data integrity.

Integration: Data management tools often integrate with other software and systems, enhancing their capabilities and enabling data flow between different parts of an organisation.

GFBio recommends two major systems with tools for biodiversity data management: Diversity Workbench (DWB) and BEXIS2 and offers training for both. DWB facilitates efficient data entry, storage, and management for biodiversity research, encompassing various data types. It enforces data standardisation to maintain consistency. BEXIS2 specialises in managing large-scale biodiversity data, integrating diverse sources for easier analysis. It emphasises metadata and documentation to provide context for datasets. Both systems can further help you during data collection. In addition, various tools exist which help you collecting and managing your data in the lLab as well as in the field such as Smatrix, RightField and Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) or Electronic Lab Notebooks2345. Smatrix and RightField aid in data collection and structuring, while LIMS systems provide comprehensive solutions for data organisation and management within laboratory environments. ELNs, on the other hand, offer digital platforms for recording, storing, and sharing experimental findings, streamlining the research process. Together, these tools play a pivotal role in advancing data management capabilities.

{{|>}}

Which of these aspects are part of a data management plan?

- [[X]] Naming those responsible for data management

- [[ ]] Vote of an ethics committee

- [[X]] Information on data archiving

- [[X]] Costs of data management and data storage

- [[X]] Information on storage and backup during the project

- [[ ]] Description of the benefits of the data management plan

- [[X]] Information on data publication

Right! There is of course much more information that should also be mentioned in a DMP, such as information on the data formats produced, data types and the estimated amount of data, in projects with several participants also information on how the data is shared within the project, or information on legal features, if existing.

Which statement is true?

- [(X)] A data management plan saves time and helps me to minimize data loss.

- [( )] I only need to create a DMP if I expect large amounts of data.

- [( )] The DMP is primarily a control instrument for funding institutions.

Right! Also, a DMP created before or with the start of the project will help you organise the research data management for you and your team. Remember, however, that it is a living document that might need adjustments at regular intervals. A well-maintained DMP can also facilitate the onboarding of new project staff with regard to research data management.

{{|>}}

Data collection is an important step of the data life cycle as it is the basis of knowledge creation. Data is collected regarding specific methods, settings and instruments. To generate comprehensible and reusable data, it is necessary to document data acquisition using metadata.

It is also possible to reuse already collected data and to integrate it into your own project. However, be aware that data integration can be very tedious. This can be data from your previous research project or data from repositories12.

Since in biology, taxonomic designations can vary depending on the source and concept used, harmonisation is necessary in some cases.

After completing this chapter, you will be able to...

{{1}}

...select appropriate tools to assist you in the data collection process

{{2}}

...recognise metadata and the benefits of metadata

{{3}}

...name important categories of metadata

{{4}}

...name selected metadata standards

{{5}}

...create your own metadata

{{6}}

...select a suitable tool for handling metadata

{{7}}

...describe your research data via metadata so that your research data can be used in the future and by machine-reading systems

{{8}}

...name the important elements of taxonomic information that are necessary to merge different species data sets

{{|>}}

Often, already existing data can help answer your research question. Searching for such data is easier with well-maintained and annotated (= enriched with metadata) data. This applies for both data providers and subsequent users. Making research data available beyond a research project allows other researchers and research groups to retrieve the data when it has become relevant for research again.

If you want to reuse already existing data, you can use different search tools, including:

-

GBIF - Free and open access to biodiversity data (especially occurrence data)

-

PANGAEA - Earth, environmental and biodiversity data

-

BacDive - Database for standardised bacterial information

It is always important to check the copyrights and licences before reusing data and seek permission when necessary.

{{|>}}

Overall, the data collection should cover the following aspects:

-

Standardised sampling protocols

-

Carrying out the experiments, observations, measurements, simulations, etc.

-

at the same time: metadata collection and creation

-

at the same time: documentation of the data collection

-

-

Generation of digital raw data (e.g. by digitising or transcribing)

-

Storage of the data in a uniform format

-

Systematic and consistent folder structure

-

Backup and management of data

It is important to create an experimental design in advance with a collection strategy on which data will be collected (What? Where? When? Who? How?) including calibration, controls, repetitions, randomisation, etc. You need to determine suitable metadata standards and methodologies, and to consider how and where to store the data and how to capture provenance (e.g. of samples and instruments). Be always aware of the data quality. If you work with sensitive, confidential, or human-related data, consider aspects such as permissions or consent, data protection, and data security.

In addition, errors occurring during data collection affect the downstream research process and in the worst-case lead to incorrect results without notice. This makes it all the more important to be careful during the data collection phase.

{{|>}}

An Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) is a software tool, which replicates a page in a paper lab notebook. You can write your observations, notes, protocols and more using your computer. An ELN has several advantages: Your notes are conserved and your colleagues or followers can repeat the same experiments, data can easily be linked with the experiment, are more traceable, more secure as well as reusable. Hence, good data management and implementation of the FAIR principles is facilitated. Some ELNs can also benefit your teamwork, for example, handle equipment use and booking, or manage inventories of supplies, chemicals or samples. There are different ELNs, with advantages and disadvantages. Some are generic, some are specialised for certain disciplines or provide specific functions e.g. drawing of chemical structures1. However, there is no ELN specifically for biodiversity and environmental data. The establishment of an ELN depends to a large extent on the individual possibilities in the working group/institution and, above all, on its own data types. The ELN Finder can help you decide which ELN fits your requirements2. A free and very flexible solution that has proven itself in the natural sciences is the cloud-based ELN eLabFTW.

!?This video published by NCSU BIT (2017) shows you how to use electronic lab notebooks.

eLabFTW is a free, secure and open source ELN for research teams. You can document your experiments and manage your lab. There is a big github community, where you can find a lot of information.

!?This video by The NOMAD Laboratory (2022) shows you how to set up eLabFTW.

{{|>}}

A crucial step in RDM is to describe your data in a way that you and other researchers can understand, find, reuse and properly cite your data. Making your data FAIR means that you need to describe the data in a structured and detailed way. A structured description of the data is called metadata. It contains information about the subject and the creator of the data, such as why, how, where and when the data was generated and what the content of the data is. To avoid errors and to create compatible and interoperable metadata, specific metadata standards can be used12.

{{|>}}

Metadata describes your data in detail. It should contain the technical details (names of datasets and data files, the file formats) and information about the data structure and processing (versioning, hard- and software, methods, tools, instruments, etc.). The descriptive metadata should further contain information about scientists/collectors and contact persons involved as well as the scientific background of the data: the hypothesis, standards, calibrations, spatial and temporal information, units, formats, codes and abbreviations12. Furthermore, each data set is accompanied by administrative information such as stakeholders, funding, access rights, etc.

Metadata ensures that research data can continue to be used today and in the future, even if the people involved in the experiments at the time are now busy with other research priorities or no longer available to provide more detailed information about the earlier experiments. Without metadata, such research data is often worthless, as it is incoherent and incomprehensible.

In order to assign metadata correctly and to be able to continue to use your data correctly and in an orderly manner, it is best to document metadata right from the start of the research project. However, metadata must be created at the latest when your research data is to be deposited in a repository, published, or archived for the long term.

Often, however, it is no longer possible to create certain metadata retrospectively. This can be the case, for example, in a long project when it is necessary to explain the provenance (origin) of the data precisely for others.

{{|>}}

Metadata always have a certain internal structure, even though the actual application can take different forms (e.g. from a simple text document to a table form to a very formalised form as an XML file that follows a certain metadata standard). The structure itself depends on the described data (for example, use of headers and legends in Excel spreadsheets versus a formalised description of a literary work in an OPAC), the intended use and the standards used. Generally speaking, metadata describe (digital) objects in a formalised and structured way. Such digital objects also include research data.

It makes sense, but is not absolutely necessary, for metadata to be readable not only by humans, but also by machines, so that research data can be processed by machines and automatically. Machines are primarily computers in this case, which is why one can also speak more precisely of readability for a computer. To achieve this, the metadata must be available in a machine-readable markup language. Research-specific standards in the markup language XML (Extensible Markup Language) are often used for this, but there are also others such as JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). When submitting (research data) publications, in most cases there is the option of entering the metadata directly into a prefabricated online form. Often it can take a substantial amount of time until a publication is submitted. Thus, it is important that metadata are collected and stored right when data are collected. A detailed knowledge of XML, JSON or other markup languages is therefore not necessarily required when creating metadata for your own project, but it can contribute to understanding how the research data is processed.

Machine readability is an essential point and becomes important, for example, when related research data are to be found by keyword search or compared with each other. A machine-readable file can be created using special programs. In the section "How do I create my metadata" you will be introduced to appropriate programs.

{{|>}}

There are many categories that can and often need to be described by metadata (Figure 4). Depending on the field and research data, these categories can differ greatly, but some are considered standard categories for all disciplines.

In the context of a citable publication, the inclusion of a 'persistent identifier' (PID) within the metadata is essential. An identifier is used for permanent and unmistakable identification (see chapter 6.4). Furthermore, the metadata should indicate who the author of the data is. In the case of research groups, all those involved in the work or who may have rights to the research data should be named. The latter should, of course, include third-party funders like the DFG, BMBF or companies that may have contributed to the funding of the research. Always make sure that the names are complete and unambiguous. If a researcher ID (e.g. ORCID) is available, this should be mentioned (see chapter 6.4).

The research topic should be described in as much detail as necessary. For best findability of the research data, it can also be useful to mention keywords that can then be used in a digital database search to achieve better results. Keywords should complement the publication title, not repeat it.

Furthermore, for the traceability of the research data, clear information is needed for parameters such as place/time/temperature/social setting, and any other conditions that make sense for the data. This also includes instruments and devices used with their exact configurations.

If specific software was used to create the research data, the name of the software must also be mentioned in the metadata. Of course, this also includes naming the software version used, as this makes it easier for researchers to repeat analyses e.g. with older versions of R, or to understand later why this data can no longer be reproduced or opened in the case of very old data.

Some metadata requirements are always the same. This also applies to the categories just listed, which are very generic. For such cases, there are subject-independent metadata standards. Other requirements can differ greatly between different disciplines. Therefore, there are subject-specific standards that cover these requirements.

, but on the other hand there is also subject-specific metadata that depends on the research area or even the research subject.

Imagine that research group 1 has created a lot of research data over several experiments of the same kind with different room temperatures. Research group 2 has conducted the same experiment with the same substances at the same room temperature and different levels of oxygen in the air and has also created research data. Research group 1 refers to the parameter "room temperature" as "rtemp" in their metadata, but research group 2 only refers to it as "temp". How do the researchers of research group 1 and how does a computer system know that the value "temp" of research group 2 is the value "rtemp" of research group 1? It's just not easily possible and thus reduces the usefulness of the data.

So how can it be ensured that both research groups use the same vocabulary (= terminology) when describing their metadata, so that in the end it is not only readable but also interpretable? For such cases, metadata standards have been and are being developed by various research communities to ensure that all researchers in a scientific discipline use the same descriptive vocabulary. This ensures interoperability between research data, which plays a crucial role in expanding knowledge when working with data.

Metadata standards thus enable a uniform design of metadata. They are a formal definition, based on the conventions of a research community, about how metadata should be collected and recorded. Despite this claim, metadata standards do not represent a static collection of rules for collecting metadata. They are dynamic and adaptable to individual needs. This is particularly necessary because research data in projects with new research methods can be very project-specific and therefore the demands on their metadata are just as strongly project-specific.

There are many different metadata standards, some are more generic (e.g. Dublin Core), others are for specific disciplines (e.g. ABCD, Darwin Core, EML, MIxS or SDD for biological data) or data types (e.g. MIABIS for biosamples, MIAME for microarrays, MIAPPE for plant phenotyping experiments). To decide which standard to use, you can have a look at the repository where you want to deposit your data, to see if they have guidelines, checklists or best practices. Some repositories (e.g. GenBank). If you are unsure which repository you are going to use, you can check the following websites for more information about the right metadata1:

-

Digital Curation Centre (DCC) -- List of Disciplinary Metadata Standards

-

Data submission templates for biodiversity, ecological and collection data - GFBio Data Centers

{{|>}}

As you have seen so far, metadata standards define the categories with which data can be described in more detail. On the one hand, these include interdisciplinary categories such as title, author, date of publication, type of study, etc., but on the other hand they also include subject-specific categories such as substance temperature in chemistry or materials science. However, there is no definition or validity check of how you fill the respective categories with information.

What date format do you use? Is the temperature given in Celsius or Fahrenheit and with "°" or "degrees"? Is it a "survey" or a "questionnaire"? These questions seem superficial at first glance, but predefined and uniform terms and formats are closely related to machine processing, search results and linkage with other research data. For example, if the date format does not correspond to the format a search system works with, the research data with the incompatible format will not be found. If questionnaires are searched for, but the term "survey" is used in the metadata, it is not certain that the associated research data will also be found.

For the purpose of linguistic standardisation in the description of metadata, so-called controlled vocabularies have been developed. In the simplest form, these can be pure word lists that regulate the use of language in the description of metadata, but also complex, structured thesauri. Thesauri are word networks that contain words and their semantic relations to other words. This makes it possible, among other things, to unambiguously resolve polysemous (ambiguous) terms (see e.g. Thesaurus of Plant Traits). A semantic thesaurus, often referred to as a semantic network, is a structured vocabulary or knowledge representation system that goes beyond traditional thesauri by capturing not only hierarchical relationships (such as broader terms and narrower terms) between concepts or terms but also semantic relationships, associations, and meaning. It is designed to provide a richer and more contextually meaningful representation of the terms or concepts within a specific domain or knowledge area. Thesauri primarily focus on managing and facilitating the retrieval of words or terms used in documents or databases. Their main purpose is to help users find synonyms, related terms, and broader or narrower terms to improve information retrieval and search. In contrast, ontologies, such as ENVO or the unit ontologies (e.g. UO) are used to represent and define complex relationships and concepts within a specific domain. They aim to capture the semantics and meaning of concepts, enabling a more comprehensive understanding within a specific domain or subject area. They serve as a formal and standardised framework for organising and categorising information, making data more accessible, interoperable, and understandable across various applications and disciplines. By providing a common vocabulary and a set of defined relationships, ontologies are invaluable tools in fields such as information retrieval, data integration, artificial intelligence, and the Semantic Web. They enable researchers and systems to achieve a shared understanding of complex domains, fostering more efficient data management and knowledge exchange.

!?This video by GFBio (2017) explains the importance of semantic search engines to find relevant data.

Ontologies and thesauri are distinct systems for structuring and categorising information. Ontologies serve to represent complex relationships and concepts within a specific domain. In contrast, thesauri primarily aid in word or term retrieval, offering synonyms, related terms, and hierarchical relationships to enhance information search and indexing. Ontologies provide a comprehensive, detailed representation of knowledge, while thesauri are more focused on managing and organising terms for search and categorization. The choice between the two depends on the specific needs and goals of a given project or application.

As a researcher or research group, how can you ensure the use of consistent terms and formats? As an individual in a scientific discipline, it is worth asking about controlled vocabularies within that discipline at the beginning of a research project. A simple search on the internet is usually enough. Even in a research group with a research project lasting several years, a controlled vocabulary should be searched for before the project begins and before the first analysis. If none can be found, it is worthwhile, depending on the number of researchers involved in the project and the number of sites involved, to create an internal project document for the uniform coordination of the terms and technical terms used, which should be used in the respective metadata categories.

GFBio provides a Terminology Service containing a collection of terminologies that are relevant in the field of biology and environmental sciences. This service acts as a resource, providing researchers with a common framework for defining and categorising various aspects of biodiversity, including species names, ecological interactions, and ecosystem processes. By utilising GFBio's Terminology Service, scientists can ensure consistency and precision in their research, promoting clarity and enabling seamless integration and comparison of biodiversity data across different studies. This unified approach to vocabulary and terminology strengthens collaboration and understanding within the scientific community, advancing our knowledge and conservation efforts in the diverse and intricate world of biodiversity.

In addition to controlled vocabularies, there are also many authority files which, in addition to uniform naming, make many entities uniquely referenceable. For example ORCID, short for Open Researcher and Contributor ID, which identifies academic and scientific authors via a unique code. The specification of such an ID distinguishes any frequently occurring and therefore ambiguous names and should hence be used as a matter of preference.

Probably the best-known standards file in Germany is the Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND, eng. Integrated Authority File), which is maintained by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNB, eng. German National Library), among others. It describes not only persons, but also "corporate bodies, conferences, geographies, subject terms and works related to cultural and scientific collections". Each entity in the GND is given its own GND ID, which uniquely references that entity. For example, Charles Darwin has the ID 118523813 and Alfred Russel Wallace has the ID 118806009 in the GND. These IDs can be used to reference Darwin and Wallace unambiguously in metadata with reference to the GND (e.g. Darwin in the DNB, Wallace in Wikidata). Another example from research is the so-called Research Organization Registry (ROR), that provides an unique identifier for each research organisation.

GeoNames is an online encyclopaedia of places, also called a gazetteer. It contains all countries and more than 11 million place names that are assigned a unique ID. This makes it possible, for example, to directly distinguish between places with the same name without knowing the officially assigned municipality code (in Germany, the postcode). For example, Manchester in the UK (2643123), Manchester in the state of New Hampshire in the US (5089178) and Manchester in the state of Connecticut in the US (4838174) can be clearly distinguished.

In general, investigate about specific requirements as soon as you know where you want to store or publish your research data. Once you know these requirements, you can create your own metadata. When referring to specific commonly known entities, always try to use a unique ID, specifying the thesaurus used.

If you want to know whether a controlled vocabulary or ontology already exists for your scientific discipline or a specific subject area, you can carry out a search at BARTOC, the "Basic Register of Thesauri, Ontologies & Classifications" as a first step. As a second step, BioPortal and the EMBL-EBI Ontology Lookup Service are very suitable resources for our domain.

{{|>}}

Metadata can be created manually or using specific tools. Tools, also for subject-specific metadata, are available online and often free to use. However, ask colleagues or data managers at your institution about established routines or licences for proprietary software commonly used in your research area. The following tools for creating metadata are only a selection (also Table 2). Maintaining tools and software packages is a lot of work, so some tools may be discontinued after a while. The important step is to add metadata to your data. Which tools you use is secondary.

A simple way to create metadata is to use a table with the elements of your chosen metadata standard as columns. You can use any spreadsheet software to set this up. For example, GBIF provides templates for occurrence data, checklist data, sampling event data and resource metadata following the metadata standard Darwin Core, an extension of Dublin Core that facilitates the sharing of information about biological diversity. GFBio provides more specific templates which also prepare sample depositions in German data centers for different sample types and taxa (organisms, tissue, molecular data, etc.). All of these templates are spreadsheets with details on minimum metadata requirements.

RightField is an open-source tool which sets up or helps you fill in simple spreadsheet tables depending on the metadata standard you choose. Ontologies can either be imported from local file systems, the web, or from the BioPortal ontology repository. RightField translates these ontologies into a spreadsheet table, and you only have to choose from the predefined terms to create your standardised metadata. You can build your own templates, too, but we highly recommend using an existing, widespread metadata standard to make your metadata findable and interoperable.

Tools with simple graphical user interfaces are not available for all metadata standards. Therefore, if you want or need to work directly with an existing XML metadata standard, you should either use the free editor Notepad++ or the paid software oXygen, if licences are available at your institution. Both editors offer better usage and display options to make content and element labels visible separately.

To create metadata in the XML metadata standard EML (Ecological Metadata Language), you can use the online tool ezEML. ezEML is free of charge and only requires a registration. It can be used as a "wizard" to guide you step-by-step through the creation of your EML document. However, ezEML also offers a range of other workflows, such as data table upload, and checking your EML document for correctness and completeness.

The open source online tool CEDAR Workbench allows online templates based on metadata standards to be created via a graphical user interface, filled in and also shared with other users. At the same time, templates created by other users can also be used for one's own research. All you need to do is register free of charge. If you are working with biodiversity survey or monitoring data, you can use the ADVANCE template in CEDAR based on a controlled vocabulary integrating terrestrial, freshwater, and marine monitoring metadata to facilitate data interoperability and analyses across realms.

The ISA framework (Investigation, Study, Assay) is suitable for experiments in the life sciences and environmental research. It is open source and consists of several programmes that can help in the management of experiments from planning and conduction to the final description. You can start with the ISA Creator, which is used to create files in the ISA-TAB format. This format is explicitly required, for example, by the Scientific Data Journal of the Nature publishing house.

Which programmes are suitable for your metadata depends very much on the type of research data and your wishes for use (also see Table 2 & Table 3). It is therefore worthwhile to talk to other researchers in advance to find the best way to create metadata for yourself. Familiarising yourself with the metadata standard relevant to you and searching for programmes that use this standard can have an advantage in terms of automatic processing of the data and later publication. At the very least, the use of a simple, subject-independent metadata standard such as Dublin Core should be considered. Of course, you should try to use the most suitable metadata standard, especially with respect to the recommendations of the chosen repository; however, there is no such thing as a perfect choice. Overall, huge effort is invested in making metadata standards interoperable in the future.

{{|>}}

Biodiversity encompasses different approaches that are related to the underlying data and organisational type such as genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity. In practice, biodiversity data is predominantly associated with species, whether you are working with proteins, genes, or ecosystem functions. Species, as fundamental biological entities, and their nomenclature serve as the backbone for the integration and synthesis needed for biodiversity research and the decision-making processes in nature conservation1.

However, species names and concepts are not static; they evolve across both space and time. Harmonising species names from various datasets is an essential aspect of data integration in the field of biological sciences2. The main reason for the diversity of taxonomies lies in the existence of multiple scientifically sound methods for defining a species. Diverse institutions and academic traditions curate a multitude of taxonomic frameworks for a wide range of taxa. These differing species concepts can diverge markedly when it comes to determining which populations should be included or excluded in the characterization of a species. It's essential to recognize that no single concept comprehensively accounts for all facets of diversity across all organisms. Equally important is understanding which taxonomic reference databases are suitable for specific taxa.

{{|>}}

The concept of a species is a multifaceted and often controversial matter, as illustrated by Charles Darwin's observation in 1859 that the distinction between species and varieties can be somewhat vague and arbitrary1. Main concepts on defining species include:

-

Biological Species Concept: This approach defines a species as a group of natural populations that either interbreed or have the potential to do so2, while being reproductively isolated from other such groups. It suits sexually reproducing organisms but is insufficient in cases like asexual reproduction, fossils, hybridization, species complexes.

-

Morphological Species Concept: Species are identified based on similar physical traits3. While intuitive, this method can be subjective due to varying trait expressions, phenotypic plasticity, and cryptic species with nearly identical appearances.

-

Phylogenetic Species Concept: It defines a species as the smallest aggregation of populations or lineages distinguishable by unique genetic characteristics4. It is well-suited for asexual species but might lead to "taxonomic inflation" and conservation challenges.

-

DNA Barcoding: DNA barcoding relies on genetic sequences, using markers like cytochrome c oxidase for animals, 16S rRNA for bacteria, and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 28S rRNA for fungi. It's a powerful tool for species identification, including eDNA5. However, it relies on reference sequences and can suffer from incomplete databases and misidentified species.

Other noteworthy concepts include the evolutionarily significant unit (conservation purposes), recognition and cohesion species (behavioural isolation), chronospecies in paleobiology, and ecological species occupying the same niche.

These concepts illuminate the diverse ways species are defined and have significant implications in various fields of biology and conservation.

{{|>}}

A species name is a hypothesis about the evolutionary relationships and distinctive characteristics between groups of organisms. The binomial nomenclature, i.e. the scientific name of a species, carries a lot of information, provided it is reported in full: Genus epithet Authority Year, e.g. Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758 (ASM Mammal Diversity Database #1005943) fetched 2023-10-09. Mammal Diversity Database. 2023.

The authority and year point to the publication of the respective species description. This publication reports a distinct set of morphological, (phylo-)genetic, geographical and/or behavioural characteristics to define a new species. Furthermore, it specifies the type, i.e. the actual specimen or group of specimens that was used to describe the new species. The type specimens are used as physical reference and usually incorporated into institutional scientific collections to facilitate long-term preservation, curation and public access. There are institutions that govern the process of naming species such as International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) or International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), but these institutions do not regulate what constitutes a species (see species concepts).

Understanding species and subspecies is crucial in conservation efforts, aiding in the organisation of breeding programs, protection of endangered species (IUCN), and wildlife trade regulation through conventions like Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). For instance, the discovery of the critically endangered Tampanuli orangutan underscored the immediate need for preservation due to habitat loss from industrial projects. CITES plays a pivotal role in regulating the international trade of over 40,000 species. Customs officers rely on databases with species names, references, synonyms, and vernacular names to enforce these regulations. The German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) provides a similar online database (WISIA) covering all species that are protected under German national or international law. Again, the database contains species names, the nomenclature references for each species or taxon, synonyms and vernacular names. Species names and respective references are also considered in many laws, ranging from fishing quotas in the Baltic Sea, compulsory environmental impact studies and mitigation efforts accompanying large building projects, to the prevention, minimisation and mitigation of the enormous detrimental effects of invasive alien species to both biodiversity and economy. In biological sciences, the integration of taxonomic data is vital for ecological research, global biodiversity trends, and decision-making. It supports initiatives like the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), which provides policy-relevant knowledge, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). This integration enhances the scientific foundation of such reports and contributes to essential functions like food security, disease prevention, carbon storage, and climate regulation12

In summary, species data integration is pivotal in safeguarding biodiversity and making informed decisions with far-reaching implications.

{{|>}}

What could possibly go wrong when you try to integrate two data sets with species names? This GBIF blog post highlights some pitfalls of matching species names from new data sets to the GBIF taxonomic backbone.

In the following there are common pitfalls:

{{1}}

Variable spelling of species name

-

Data set 1: Carabus arvensis Herbst 1784 (valid name)

-

Data set 2: Carabus arcensis Herbst 1784 (Synonym)

-

Data set 3: Carabus aruensis Herbst 1784 (misspelt epithet)

{{2}}

Variable spelling of authority

-

Data set 1: Carabus arvensis Herbst 1784

-

Data set 2: Carabus arvensis Hbst., 1784 (official abbreviation of authority)

-

Data set 3: Carabus arvensis Hrst. 1784 (misspelt abbreviation of authority)

{{3}}

Missing authority

-

Data set 1: Glocianus punctiger

-

Synonym of Rhynchaenus punctiger Sahlb., 1834-39

-

Data set 2: Glocianus punctiger

-

Synonym of Ceuthorhynchus punctiger Gyllenhal, 1837

{{4}} Mismatch of ranks

-

Data set 1: Carabus arvensis Herbst 1784

-

Data set 2 (Red List Germany 2009 ff., red-list status was evaluated for three subspecies):

-

Carabus arvensis arvensis Herbst, 1784 - Vorwarnliste (similar to IUCN Red List Near threatened (NT), but different methodology)

-

Carabus arvensis noricus Sokolar, 1910 - Ungefährdet (similar to IUCN Red List Least concern (LC), but different methodology)

-

Carabus arvensis sylvaticus Dejean, 1826 - Gefährdet (similar to IUCN Red List Endangered (ED), but different methodology)

-

Data set 3: Carabus sp.

-

Data set 4: Carabidae sp. 4

{{|>}}

To integrate taxonomic data sets for your own purposes, you should match the two sets of species names against a taxonomic reference database. Many databases are using alphanumeric unique taxon identifiers (UTI) additionally to species names to facilitate taxonomic data integration. A multitude of software tools and R packages helps to access and use these taxonomic databases, matching both UTIs and species names. Many research teams are working hard to improve taxonomic integration at all levels of data curation: Schellenberger Costa et al. (2023) compared four global authoritative checklists for vascular plants and proposed workflows to better integrate these important databases in the future1, Grenié et al. (2021) compiled a living database of taxonomic databases and R packages2 and gave an overview of tools, databases and best practices for matching species names3, and Sandall et al. (2023) proposed key elements of a global integrated structure of taxonomy (GIST) to reconcile different aspects, approaches and cultures of taxonomy4.

Taxonomic databases serve specific tasks and encompass different aspects of biodiversity. The suitability of a particular database for your project depends on the type of data you are looking for 4:

-

Databases creating new taxonomic frameworks: Examples include FishBase, Avibase, Amphibian Species of the World (ASW). These databases develop novel taxonomic backbones.

-

Databases aggregating primary taxonomic lists and linking databases: Notable databases in this category are the Catalogue of Life (COL+), Encyclopedia of Life (EoL). They bring together primary taxonomic information and link various databases.

-

Databases combining new frameworks and taxonomic lists: Databases like ITIS and WoRMS fall into this category. They not only produce new taxonomic backbones but also integrate primary taxonomic lists.

-

Databases focused on biodiversity data aggregation: This group includes databases like GBIF, OBIS, Map of Life (MOL), INSDC and IUCN. While not primarily taxonomic, their main purpose is to aggregate and provide comprehensive biodiversity data.

Understanding the nature and focus of these databases is essential in choosing the right one for your research or project. If you are re-using taxonomic data collected by others, you should therefore take care for

-

Find out which taxonomic reference was used to identify the species

-

Consider the possibility of misidentification (e.g. if a genetic sequence is not linked to a voucher specimen, or if the authority is missing)

-

Consider the possibility of misspelling of both species names and authority names

-

Select a taxonomic backbone that is complete and suitable for your taxon of interest for taxonomic harmonisation

If you are collecting new taxonomic data yourself, or in collaboration with taxonomic experts, you should additionally take care to

-

Note the scientific name and authority of a species

-

Note the identification literature that was used to identify specimens and the person(s) who identified specimens (when working with taxonomic experts: ask them which reference literature they used)

-

Note the taxonomic references for each taxon, i.e. which taxonomic references the used identification literature is based on

-

Note the place and date when you found a specimen

-

Note details about the method used to record an occurrence

Species names connect physical, functional, spatial, and genetic data sets. Providing detailed taxonomic metadata will help to keep your data alive and re-usable for your own and for others research.

{{|>}}

How do I collect metadata?

- [(X)] I enquire about suitable metadata standards before starting research and collect as much metadata as possible to ensure that the data can also be understood by other researchers.

- [( )] I simply transfer the metadata from another project.

- [( )] I always follow the same scheme, no matter what type of research data it is.

Correct! But it really won't hurt to ask colleagues of the same discipline whether there are any known suitable metadata standards and how they should be applied.

When should the associated metadata be deleted if research data is deleted from a repository?

- [(X)] Preferably not at all. If research data is withdrawn, the metadata provides an overview of the project and possibly why the data was withdrawn.

- [( )] The metadata is deleted together with the research data.

- [( )] For legal reasons, the metadata must remain in the repository for at least one year.

Correct! One reason, above all, is the obligation to provide proof of research data. If, for example, a text was published in 2017 that examined data from 2015, but in 2019 it turns out that the data collected at that time violated certain legal requirements, the text must still retain evidence that this research data actually still existed and was accessible at the time of publication, and also information about what this data contained.

What exactly is metadata?

- [(X)] Metadata describes other data of any kind in a structured way and helps to understand this data.

- [( )] Metadata is data that stores information about files in encrypted form.

- [( )] Metadata is used to make the actual research data available, as it would otherwise not be accessible.

Correct! Metadata is data about data. Metadata therefore contain descriptive information to understand another or the described data set. Understanding the described data is mostly dependent on already having expertise in dealing with this type of data through one's own research or studies.

How should metadata ideally be stored?

- [( )] I create metadata according to my own schema according to the requirements of my own research data.

- [(X)] Metadata should be created according to specific metadata standards.

- [( )]Metadata should only be readable by myself in order to protect my research data.

Correct. Ideally, metadata should be available as subject-specific standards. However, this is not always the case, so depending on the research project, metadata sometimes has to be created.

What is the correct order of a species name?

[[lowii | J. E. Gray | (Ptilocercus) | 1848 ]][[ 1848 | Ptilocercus | J. E. Gray | (lowii) ]][[ 1848 | (J. E. Gray) | lowii| Ptilocercus ]][[ J. E. Gray | Ptilocercus | lowii | (1848) ]]

Correct! Species names consist of Genus, epithet, authority, and year of publication of the species description.

The pen-tailed treeshrew (Ptilocercus lowii J. E. Gray, 1848) is a treeshrew of the family Ptilocercidae native to southern Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, and some Indonesian islands. In a study of wild pen-tailed treeshrews, the animals frequently consumed large amounts of fermented nectar, equivalent of 10–12 glasses of wine adjusted to body weight with an alcohol content up to 3.8%. The pen-tailed treeshrews did not show any signs of intoxication, probably because they use a different pathway to metabolize alcohol compared to humans.

What is the correct order of a species name?

[[ Fresen | oligospora | (Arthrobotrys) | 1850 ]] [[ Arthrobotrys | 1850 | Fresen | (oligospora) ]] [[ 1850 | oligospora |Arthrobotrys | (Fresen) |]] [[ Arthrobotrys | (1850) | Fresen | oligospora ]]

Correct! Species names consist of Genus, epithet, authority, and year of publication of the species description.

Arthrobotrys oligospora Fresen. (1850) is a nematode-capturing fungus. In low nitrogen environments, it grows sticky nets from hyphae and attracts nematodes with semiochemicals1 that nematodes use to communicate with each other. Small nematodes can be caught with a single loop. The more the nematodes struggle to escape, the more they are glued to the net. Finally, the nematodes are paralysed and digested by hyphae growing into their bodies.

What is the correct order of a species name?

[[ (Cymothoa) | exigua | Schiødte & Meinert | 1884 ]] [[ Cymothoa | (exigua) | Schiødte & Meinert | 1884 ]][[ Cymothoa | exigua | (Schiødte & Meinert) | 1884 ]] [[ Cymothoa | exigua | Schiødte & Meinert | (1884) ]]

Correct! Species names consist of Genus, epithet, authority, and year of publication of the species description.

Cymothoa exigua (Schiødte & Meinert, 1884), the tongue-eating louse, is a parasitic isopod of the family Cymothoidae. Females attach to the tongue and sever the blood vessels. When the tongue falls off, the female attaches itself to the remaining stub of tongue and the parasite itself effectively serves as the fish's new "tongue". The parasite feeds on the host's blood and mucus. Juveniles likely first attach to the gills of a fish and become males. As they mature, they become females, with mating likely occurring on the gills.

What is the correct order of a species name?

[[ (Ailanthus) | altissima | Mill. | Swingle ]][[ Ailanthus | (altissima) | Mill. | Swingle ]][[ Ailanthus | altissima | (Mill.) | Swingle ]][[ Ailanthus | altissima | Mill. | (Swingle) ]]

Correct! Species names of plants consist of Genus, epithet, and authority.

Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle is a deciduous tree native to northeast and central China, and Taiwan. The tree grows rapidly and is very tolerant of pollution. It is considered to be one of the worst invasive species in Europe and North America. It spreads aggressively both by seeds and vegetatively by very long root sprouts, often "tunneling" even below wide streets and crossroads. This "tree of heaven" inhibits the growth of other plants in their sourroundings. Oh, and the male flowers have a very distinctive smell...

{{|>}}

Data analysis enables you to uncover hidden insights and correlations within the data, ultimately leading to the creation of knowledge. The nature of this analysis can vary significantly, depending on the heterogeneity of the data at hand. You, as the data analyst, are best equipped to determine the most appropriate methods for your specific dataset. However, it's imperative to adhere to and document the standards and methods commonly accepted within your field. You may employ a range of tools and software, including application-specific software or programming languages like Python and R123.

Given that data analysis yields critical research outcomes, it's of utmost importance that the entire analysis workflow is thoroughly documented, published, and aligns with FAIR principles. This approach ensures the reproducibility of your results456. In our data-driven world, effective data analysis is paramount for informed decision-making across diverse domains. However, access to data alone is insufficient; it must be managed and analysed in a manner that guarantees it meets the criteria of being FAIR. This can be assured by providing code you used/produced for your analysis, execution environments, and data analysis workflows.

After completing this chapter, you will be able to...

{{1}}

...name useful tools to document your data analysis workflow

{{2}}

...explain why code management helps to make your data analyses more transparent

{{|>}}

Code Management: A fundamental aspect of FAIR analysis is the organisation, accessibility, and version control of your code. Git repositories are invaluable for effective code management. Here are key considerations:

-

Git Basics: Familiarise yourself with Git, including core concepts like commits, branches, and pull requests. You could e.g. start with the introductory course on version control by the Software Carpentries or this tutorial.

-

Repository Structure: Maintain a clear and structured directory layout for your codebase. Suggestions and examples for useful structures are here, here and here.

-

Documentation: Thoroughly document your code to ensure it's comprehensible to others. Here are some basic suggestions. Advanced R users can e.g. use package roxygen2.

{{|>}}

Execution Environment: Enhance your code's accessibility and reproducibility by embracing package and environment management systems. These specialised tools empower fellow researchers to seamlessly install the precise tool versions, including older ones, within a controlled environment. This ensures that they can execute your code in an equivalent computational setup, complete with all necessary dependencies, such as the correct version of R and specific libraries and packages:

-

Bioconda: Bioconda is a specialised distribution of bioinformatics software that simplifies the installation and management of tools and packages for biological data analysis. Here is a tutorial to get started.

-

mybinder.org: MyBinder enables the creation of interactive and executable environments directly from your code repositories, simplifying the process for others to replicate your analyses. Here is a tutorial to get started. You can also follow the novice Python lesson by the Software Carpentry which uses binder.

{{|>}}

Data Analysis Workflows: To conduct FAIR analysis, it's essential to select appropriate data analysis workflows. Tools such as Jupyter Notebook and R Markdown facilitate transparent and reproducible analyses:

-

Jupyter Notebooks: Jupyter provides an interactive environment for data exploration and analysis, allowing you to seamlessly blend code (such as R, Julia, Python), visualisations, and narrative explanations in a single document. You can try Jupyter Notebooks in your browser with a programming language of your choice.

-

R Markdown: R Markdown combines R code with markdown text, empowering you to create dynamic reports and documents that are easily shareable and reproducible.

{{|>}}

By embracing these principles and utilising tools like Git, Bioconda, mybinder.org, Jupyter, and R Markdown, you'll be better equipped to perform data analysis that not only adheres to FAIR principles but also fosters transparency, accessibility, and collaboration. This approach contributes to the advancement of research and science in our data-driven era. An illustrative example of FAIR analysis was produced in the context of the NFDI4Biodiversity and GfÖ Winter School 2022 in the form of a Jupyter Notebook.

{{|>}}

Which of these are tools to organize your data analysis?

- [[Tools for data analysis] (Not a tool for data analysis)]

- [ (X) ( ) ] Jupyter

- [ (X) ( ) ] Binder

- [ (X) ( ) ] Git

- [ (X) ( ) ] RMarkdown

- [ (X) ( ) ] Python