This repository provides results and code for the project "Prediction of protein-protein binding affinity"

Authors:

- Anastasiia Kazovskaia (Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- Mikhail Polovinkin (Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia)

Supervisors:

- Olga Lebedenko (BioNMR laboratory, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- Nikolai Skrynnikov (BioNMR laboratory, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia)

Table of contents:

The binding constant is a value characterizing the complex sustainability, which is significantly important in drug design and mutation analysis. It is strongly related to the difference of free energies in the system before and after complex formation.

Goal: The main goal of this project is to develop a neural network model predicting a protein-protein interaction dissociation constant using the compound structure.

Objectives:

- Develop train-test pipeline for neural networks (NN)

- Predict electrostatic energy of randomly generated chain-like molecules

- Predict binding free energy of real dimer complexes obtained in MM/GBSA method

- Predict dissociation constant of real dimer complexes

|

|---|

| Figure 1. The main idea behind the study. |

Prior to implementing transfer learning procedure, we developed and adjusted train-test neural network pipeline with electrostatic energy prediction problem.

-

Electrostatic energy prediction. As a rough approximation of our problem, we considered a well-defined one: prediction of electrostatic energy for chain-like molecules. This problem has a direct solution, the Coulomb law, and it is suitable and convenient for pipeline development and model adjustment. The dataset consisted of chain-like molecules with electrostatic energy calculated for them. The self-avoiding random walk algorithm [2] was implemented to obtain structures of chain-like molecules, the distance between two adjacent atom-points was set to 1.53 A (the length of

$C$ -$C$ bond). After chain-like molecules generation we assigned charges from uniform distribution$U[-1;1]$ to all point-atoms in molecules. Targets were calculated for all chain-like molecules according to the Coulomb law. We implemented, trained and tested two types of neural networks to predict electrostatic energy: one consisting of several fully-connected layers (FC model) considered as a baseline and graph attention neural network with both vertex and edge convolutions (GAT). The FC model operated with the set of coordinates and charges of point-atoms. Prior to training the FC model, we augmented the dataset by rotating the chain-molecules to enforce the model to learn the rotational invariance. 15000 objects (3000 unique molecules) were in dataset for FC training. In case of the GAT model, the input data consisted of graphs corresponding to the chain-like molecules. For all generated chain-like molecules the complete graphs were created. The nodes corresponded to the point-atoms, the charge of a point-atom was the only node feature, a distance between point-atoms connected with the current edge was set as an edge feature. There were 5000 graphs in train sample. The molecules of length 2, 16 and 32 atoms were considered. - GBSA free energy prediction. As a more complex and consistent problem, we considered prediction of free energy of protein-protein complexes estimated with MM/GBSA method [3], [4]. The PDB ids of dimer complexes (both hetero- and homo- dimers) were obtained from Dockground database. To avoid redundancy in data we clustered complexes with respect to their amino acid sequences. To solve the clusterization problem we used RCSB database of sequence clusters with 30% similarity threshold. Both sequences in each complex were matched to their clusters with respect to RCSB database resulting in a pair of cluster numbers for complex, this unordered pair is thought to be a complex cluster label. Free energy (dG) was estimated with the GBSA method for all of the structures employing Amber package [5]. The calculation of dG for GBSA dataset adhered to the following pipeline. The raw PDBs were processed via biobb [6] to fix the heavy atom absence, and complex geometries were minimized employing the phenix package [7]. Hydrogens obtained from solving the structure were removed using Amber package. We used the PDB2PQR tool [8] to protonate complexes in target acidity (pH = 7.2). Finally, dG for complexes were calculated within the MM/GBSA method in Amber. The obtained dataset was then splitted into train, validation and test samples with respect to the clasterization. This guaranteed homogeneity of the data and absence of outliers in the samples. The dataset consisted of 10725 complexes in total: 5 668 complexes in the train, 3 188 in the validation, and 1 869 in the test sample. Protein-protein interaction interfaces were extracted from PDBs of complexes: a residue of one interacting chain belonged to the interface if distance between any of its atoms and any atom of other interacting chain was less than a cutoff parameter (cutoff = 5A). Large interfaces containing more than 1000 atoms were dropped from the datasets due to their high memory usage while training. Interfaces were then processed into graphs for a graph neural network. One-hot encoding technique with the respect to Amber atom types was applied to construct features for graph nodes, pairwise distances between connected atoms were used as edge features. We implemented, trained and tested one more type of graph neural networks to predict GBSA free energy: GAT model with both vertex and edge attention mechanisms. The internal embedding size was set to 16.

-

$K_d$ prediction. We decided to predict$\ln(K_d)$ to avoid issues with losses and metrics and make the problem a little closer to the previous one. In this part of our study we used GAT predicting model accepting as input features either embeddings extracted from GAT model trained on GBSA dataset, or from ProteinMPNN's encoder. ProteinMPNN model [9] is developed to predict the amino acid sequence by the structure of a protein or protein-protein complex. Therefore, its embeddings potentially contain the relevant information about the complex structure, so can be used to solve our problem. We extracted embeddings fromca_model_weights/v_48_002.ptmodel checkpoint. This model considers$C_\alpha$ atoms only. The embedding dimension is default and equals to 128. As a core of$K_d$ prediction dataset PDBbind database [10] was chosen. PDBbind contains complex ids, resolutions of structures, experimentally measured$K_d$ values, and other useful data. We filtered out the poorly solved structures in order to reduce the noise level in the data. Structures with resolution lower than 5A were dropped from the data. PDBs were then processed in order to extract interfaces (the same cutoff parameter) and construct graphs. The resulting dataset contained about 1300 objects (pairs of interface graph and$\ln(K_d)$ ) in total. Train, validation and test datasets were obtained by random splitting with relative sizes 0.7, 0.2 and 0.1, respectively.

Key packages and programs:

- the majority of scripts are written on

Python3and there are alsobashscripts slurm(20.11.8) cluster management and job scheduling system- pyxmolpp2 (1.6.0) in-house python library for processing molecular structures and MD trajectories

- pytorch (1.13.1+cu11.7) the core of NN workflow

- pytorch geometric (2.2.0) the core of graph NN models

- biobb software library for biomolecular simulation workflows

- phenix software package for macromolecular structure determination

- PDB2PQR a preparing structures for continuum solvation calculations library

- Amber20 (a build with MPI is employed and is highly preferrable)

- other python libraries used are listed in

requirements.txt

- PPINN contains core project files

-

data_preparation contains examples for data preparation from raw pdb-files for both GBSA and

$K_d$ prediction - electrostatics contains examples for electrostatic energy of chain-like molecules prediction

- figures contains figures for README.md you are currently reading

- gbsa contains examples for GBSA energy of real molecules prediction

-

kd contains examples for

$\ln(K_d)$ prediction

This section analyzes the serviceability of the proposed method to predict electrostatic energy, MM/GBSA free energy and

In case of electrostatic energy prediction of molecules of length 2, 16 and 32 atoms were considered. Distributions of electrostatic energies over the train samples are provided in the figure below.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Electrostatic energy distributions in the train, validation, and test samples, respectively. |

The distribution for pairs of charges corresponds to the theoretical predictions (the problem of distribution of product of two uniform distributions). Coulomb energy distributions in case of molecules with the bigger number of atoms are much more complex. These have peaks near zero energy and small non-zero kurtosis. Cases of 16 and 32 molecules are quite similar, but the bigger molecules have a wider conformation space and, as a result, more spread energy distribution. In further analysis some similarities in electrostatic energy and dG distributions were observed. These similarities can be explained by the presence of electrostatic interaction contribution in the free energy of complex binding.

|

|---|

| Figure 3. Electrostatic energy prediction: losses of the train and validation samples during training. |

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Electrostatic energy prediction: correlation plots on the test samples. |

In Figure 3 MSE-losses for the train and validation dependence on the epoch is presented for FC and GAT models. The correlation plots for the test samples are also provided (Figure 4). Both models learned to perfectly predict Coulomb law in case of two atom interactions, the correlations are equal to 1. With an increase of chain-like molecule size, the lack of FC model capacity appeared. Note that FC model struggled to learn rotational invariance: without the augmentation procedure the perfomance was even worse. GAT architecture, on the contrary, did not experience such issues. The results of testing on the samples of chain-like molecules with 16 and 32 atoms are the following: 0.69 and 0.50 for FC opposed to 0.94 and 0.84 for GAT, respectively. Hence, we could make a conclusion that predictive power of GAT architecture is significantly higher than the FC model’s one. In consequent tasks we employed GAT architectures due the higher perfomance.

Here we provide the results of training GAT model on the GBSA problem.

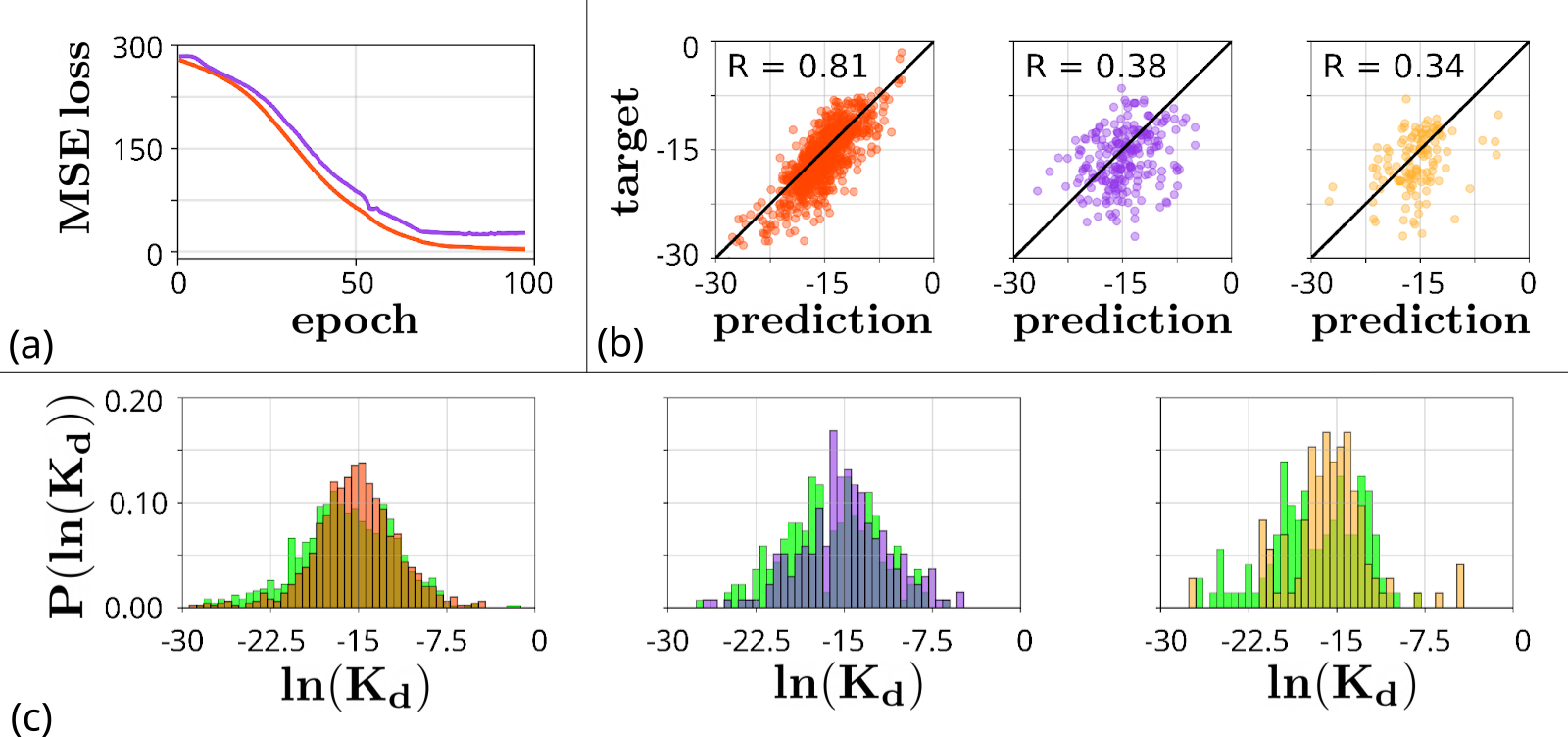

Despite the fact that GAT model did not manage to achieve zero MSE-loss while training (Figure 5(a)), it demonstrated a consistent correlation on the test sample. Thanksgiving to careful and crafty dataset splitting into train, validation and test samples, the GAT model fitted the train sample well averting an overfitting issue. Green charts at the back of the graphs corresponding to target dG distributions (for train, validation and test samples) are identical and are accurately spanned with red, purple, and yellow prediction distributions (for train, validation and test samples, respectively), which is presented in Figure 5(c). Contiguous correlation coefficients together with quite precise prediction distributions attest the fact that the model trained without overfitting: 0.74 on the train sample, 0.74 on the validation sample, and 0.72 on the test sample (Figure 5(b)). These results let us consider GBSA prediction task properly solved.

We expected embeddings to be capable of capturing all of the necessary information about the interfaces, and so, we were able to proceed to the main

Alternatively, to predict

As can be seen from Figure 6(a), the model tended to overfit: MSE-loss decreased faster in the train sample than in the validation one. Correlation coefficients also attest this: 0.81 on the train sample, 0.38 on the validation sample, and 0.34 on the test sample (Figure 6(b)). We deem this result is due to a random splitting into train, validation and test samples:

All the assigned goals were accomplished. Indeed, our results verify a common insight on graph neural networks: this kind of models is an extremely powerful and robust method for predicting physical characteristics of molecules. In our project we successfully predicted energy of electrostatic interaction for a set of charged points and binding free energy for protein-protein complexes within the MM/GBSA approximation. We also proposed an exceedingly promising approach to

We intend to continue the project. In our opinion, there is a groundwork for improving our result. First of all, we demand to expand the

[1] Kastritis P.L. and Bonvin A.M. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: daring to ask why proteins interact. 2012. J. R. Soc. Interface. 10(79):20120835. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0835.

[2] Rosenbluth M. and Rosenbluth A. Monte Carlo Calculation of the Average Extension of Molecular Chains. 1995. J. Chem. Phys. 23(2): 356–359. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1741967

[3] Kollman, P. A., Massova, I., Reyes, C. et al. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. 2000. Accounts of Chemical Research. 33(12): 889-897. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar000033j

[4] Genheden, S. and Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. 2015. Expert opinion on drug discovery. 10(5): 1-13 https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936

[5] D.A. Case, H.M. Aktulga, K. Belfon et al. 2023. Amber 2023, University of California, San Francisco.

[6] Andrio, P., Hospital, A., Conejero, J. et al. BioExcel Building Blocks, a software library for interoperable biomolecular simulation workflows. 2019. Sci Data. 6, 169. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0177-4

[7] Liebschner, D., Afonine, P. V., Baker, M. L. et al. 2019. Macromolecular structure determination using x-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 75, 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2059798319011471

[8] Dolinsky, T. D., Czodrowski, P., Li, H. et al. 2007. PDB2PQR: expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. 2007. Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 35, Issue suppl_2, 1 July , Pages W522–W525, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm276

[9] Dauparas, J., Anishchenko, I., Bennett, N., et al. 2022. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science. 378: 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add2187

[10] Su, M., Yang, Q., Du, Y. et al. Comparative Assessment of Scoring Functions: The CASF-2016 Update. 2019. Journal of chemical information and modeling, 59(2): 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00545

[11] Jankauskaitė, J., Jiménez-García, B., Dapkūnas, J., Fernández-Recio, J., Moal, I.H. 2019. SKEMPI 2.0: an updated benchmark of changes in protein–protein binding energy, kinetics and thermodynamics upon mutation. Bioinformatics 35: 462–469 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty635

[12] Ridha, F., Kulandaisamy, A., Gromiha, M. M. MPAD: A Database for Binding Affinity of Membrane Protein–protein Complexes and their Mutants. 2022. Journal of Molecular Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167870