Utter the words “Burning Man,” and a debate may immediately follow. The annual nine-day event just before Labor Day in the Black Rock Desert (or Middle of Nowhere, Nevada) almost always inspires an ocean of opinions—passionate, provocative, and perhaps polarizing.

For instance, a 2014 article in the New York Times acknowledged the perception that Burning Man is “a white-hot desert filled with 50,000 stoned, half-naked hippies doing sun salutations while techno music thumps through the air”—and called this perception “mostly correct.”

On the other hand, a 2015 article in the business magazine Inc. claimed that Burning Man had become a must-see event for “Silicon Valley’s wealthiest tech entrepreneurs [who] escape for a week over Labor Day weekend.” One of those entrepreneurs, Elon Musk, reportedly observed, “If you haven’t been, you just don’t get it.”

And when the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum created a pioneering exhibition titled No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man, it referred to Burning Man as “a hotbed of artistic ingenuity . . . both a cultural movement and an annual event, [which] remains one of the most influential phenomenons in contemporary American art and culture.”

As someone who previously knew very little about Burning Man, but who had heard mostly the New York Times perspective, I visited the Renwick exhibition in April 2018 and was both amazed and fascinated. One delight for me was to learn about the Ten Principles, which aim to guide the “ethos and culture” of the Burning Man community. Nearly all of the principles—and particularly civic responsibility, decommodification, gifting, leaving no trace, and radical self-reliance—struck a responsive chord.

Moreover, as a folklorist, I was particularly intrigued by the notion that Burning Man was primarily a folk group, in which tens of thousands of participants—known as Burners—join together for one week in the Nevada desert to create a community based on a shared identity and shared values. According to Mary Hufford’s definition, cited by the American Folklore Society, “Folklife is community life and values, artfully expressed in myriad forms and interactions.” I figured that if I could ever get to Burning Man, I would try to investigate and document the folk culture of this very distinctive community.

Almost exactly one year after marveling at the Renwick exhibition, I entered Burning Man’s Main Ticket Sale with low expectations. The population of Burning Man is capped at roughly 80,000, with tickets sold to some 70,000 individuals. If you’ve previously been part of a “proven collaborative group,” you can purchase one of 32,000 tickets sold through the Directed Group Sale, which takes place two months earlier. The Main Sale offers 23,000 tickets—usually gone within thirty minutes—to the general public, some of them first-timers like me. This year’s Main Sale experienced technical glitches that brought the system to a near halt, as thousands watched a spinning icon for hours. Somehow I got lucky: I had to wait only two hours and thirty minutes for the coveted ticket-purchase page to pop up on my computer screen.

One of the criticisms justly leveled at Burning Man is that it is expensive. My Main Sale ticket cost $425. Adding Nevada state tax, delivery fee, and credit card fee brought the price to nearly $500. Then there’s the cost of getting there, which for me meant round-trip airfare to Reno; hotel rooms near the Reno Airport for both the inbound and outbound trips; the Burner Express Bus from the Reno Airport to Black Rock City; renting a bicycle to navigate the vast distances of the Playa (Spanish for beach, which describes the dried prehistoric lakebed where Burning Man takes place); and providing everything one needs—primarily shelter, water, and food—for the duration.

Critics maintain that these costs make Burning Man an event primarily for the well-to-do. Certainly, there are wealthy people there, some of whom stay in RVs that have flush toilets and showers. However, on the Playa you don’t know who those people are. Everyone is equally covered by the fine alkaline particles known as Playa Dust. Burning Man does sell some 4,500 low-income tickets, but even these cost $210. Many of the Burners with whom I spoke told me that they carefully save money throughout the year in order to afford the trip, or that they are able to attend only every other year. Moreover, on the Playa itself, I could find only two places where money is exchanged: the building known as Arctica, which sells bags of ice; and the Center Café, which sells coffee. Nearly everywhere else, the principle of gifting is paramount.

-

1 / 6The author at Burning ManPhoto by Tyler Nelson

-

2 / 6Photo by Tyler Nelson

-

3 / 6Photo by Tyler Nelson

-

4 / 6Photo by Tyler Nelson

-

5 / 6Photo by Tyler Nelson

-

6 / 6Photo by Tyler Nelson

One of those gifts seems to be the gift of gab. Striking up conversations with fellow Burners—almost all of whom were complete strangers—was not only the highlight of my Burning Man experience, but also perhaps the defining characteristic of this particular folk community. As Lara, a helicopter pilot from Louisiana, told me, “This is a very special place. It is bleak and hard, but it also brings hope. It’s a judgement-free zone, where you don’t have to justify yourself. So many people come here and find an extraordinary power in the people and the place that can accomplish marvelous things. Magical things can happen, and you have to be open to accept those things.”

To facilitate this acceptance of new things and new experiences, many Burners have a Playa Name, which they use (sometimes exclusively) for their life on the Playa. “Your Playa Name allows you to start anew,” King Mango, an artist-activist from Florida, told me. According to tradition, you do not get to pick your Playa Name; rather someone else gives it to you. Marshmallow, an otolaryngologist from Southern California, told me she has no idea how she got her Playa Name. Her husband’s is No Pants, which is more easily explicated.

From a folkloristic perspective, a Playa Name is an example of folk speech, which refers to the expressions, pronunciations, and grammatical forms shared by members of a particular folk group—whether the group is based on region, religion, ethnicity, occupation, kinship, or gender identity. The citizens of Black Rock City form one such group, and have a distinctive vocabulary that is shared among themselves. Among the favorites that I heard:

- MOOP—an acronym for Matter Out Of Place, meaning litter or anything that did not originate on the Playa

- Sparkle pony—“Derogatory term for a participant who fails to embrace the principle of radical self-reliance, and is overly reliant on the resources of friends, campmates, and the community at large to enable their Burning Man experience. Often fashionably attired, since they packed nothing but costumes,” according to the Burning Man glossary.

- Sparkle donkey—a less beautiful version of the sparkle pony, but equally unprepared for life on the Playa. Burners take very seriously the principles of radical self-reliance and gifting, for which the ponies and donkeys are apparently unprepared.

Other forms of folk speech at Burning Man include proverbs and/or aphorisms. One of my favorites, which I heard from several sources is “The Playa provides.” As Lara explained to me, “Whenever I have needed something, it has just manifested itself.” King Mango shared with me a similar expression: “Out of nothing, we make everything,” which some attribute to Larry Harvey, the cofounder of Burning Man.

Two other examples, which I heard from Mojito Molly, an archivist and folklorist in the D.C. area, are “Next year was better” and “Safety third.” Finally, according to curator Nora Atkinson, the title of the Renwick exhibition, No Spectators is “a long-standing saying on Playa. You are encouraged to fully participate. It’s all about being there, being fully present, and not just observing. Two of the ten principles of Burning Man are radical participation and radical inclusivity, meaning that there are no outsiders. Everyone is part of the experience.”

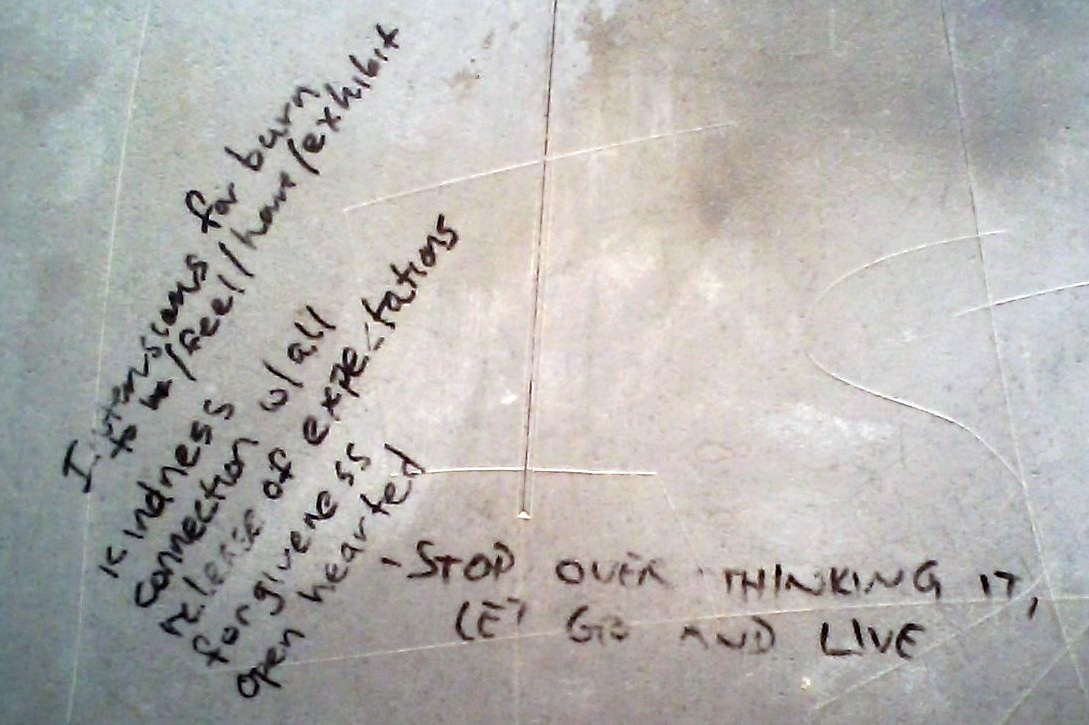

Still another form of folk speech clearly evident at Burning Man is latrinalia, which refers to inscriptions or graffiti written on the walls of latrines or toilets, often in conversation. Defecation or urination on the Playa is strictly prohibited—as it would violate the principle of leaving no trace—so portable toilets proliferate throughout Black Rock City. One of my favorite examples of latrinalia was “I have dust in weird places.” But the one that perhaps best represents the spirit of Burning Man was the following exchange:

One hand had written,

Intensions [sic] for burn

to be / feel / have / exhibit

kindness

connection w/all

release of expectations

forgiveness

open hearted

To which another hand responded,

Stop over-thinking it, let go and live.

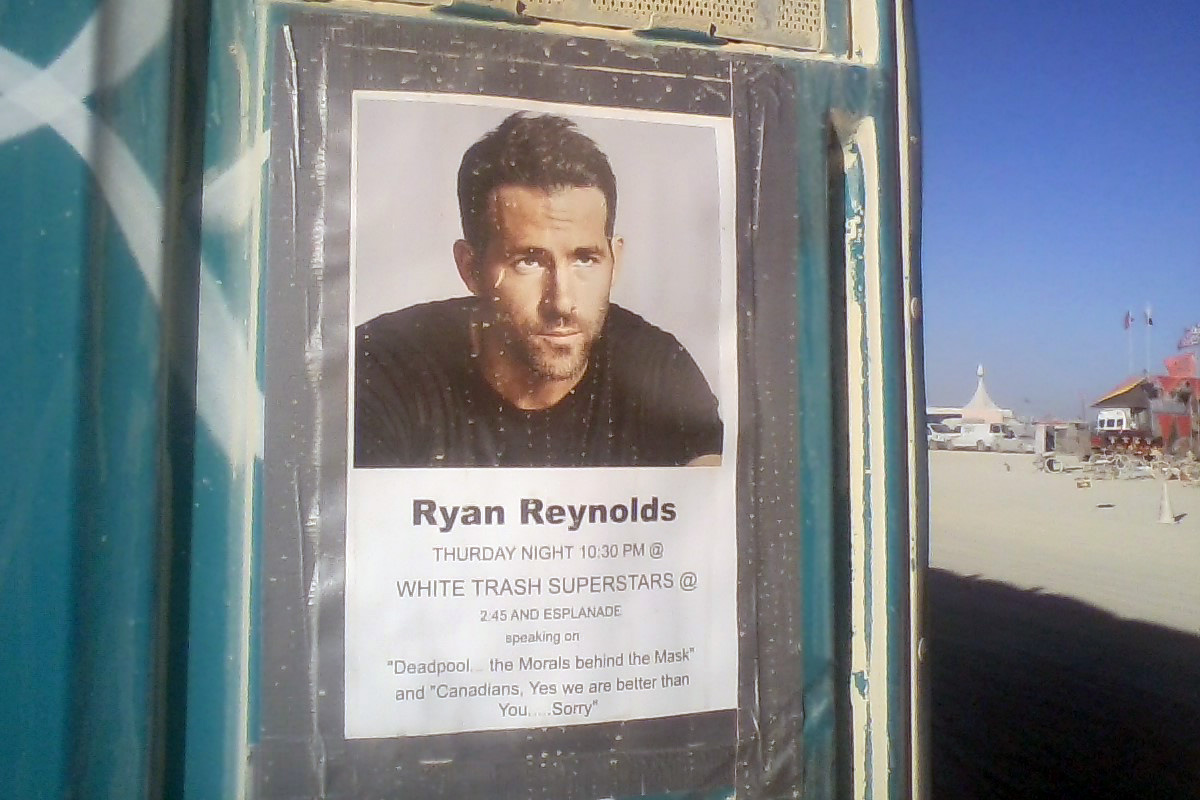

Legends constitute one of the most common folk genres. As defined by folklorists, legends are stories believed to be true, which are always set in real time and in the real world—in contrast to myths, which take place before the beginning of time and before the world (as we know it) was created. One of the legends I heard this year at Burning Man concerned the Nevada water moccasin, which purportedly lurk inside the portable toilets, waiting to strike. However, Joey X, a Burner since the mid-1990s who does post-production advertising in New York, told me that this particular legend may have been invented by pranksters in the Playa Rumor Society. And I honestly don’t know if there really is a Playa Rumor Society. Another legend—disseminated via poster—was that film and television star Ryan Reynolds would be speaking at Burning Man.

Perhaps the folk genre most closely associated with Burning Man is ritual, which is based on traditional beliefs and customs. Indeed, cofounder Larry Harvey often used the word ritual to describe the annual burning of the Man, which began almost spontaneously in 1986 on Baker Beach in San Francisco. But ever since the Burning Man event moved to the Black Rock Desert in 1990, the rituals have become more entrenched. For instance, all first-timers are asked to make a dust angel in the Playa Dust and ring a bell to signal their arrival. Burners howl and cheer when they see both the sun rise and the sun set. They go to the Temple for contemplation, mourning, and leaving behind memories for those who have passed.

“Burning Man is about the embracing of ritual,” said Gary, a retired engineer from Seattle who now produces art on the Playa. “I gave up the rituals of religion, but I like the rituals of Burning Man. I have to visit the Temple and I have to see the Man burn. There is a desire here to adapt rituals. You have people here who are highly individualistic, but they also want to be wearing the right thing. They always wear a tutu on Tutu Tuesday.”

Joey X provided additional examples: “On the night of the Burn, we get dressed up and sit together. Once the Man burns, there are hugs and kisses, and wishes of ‘Happy Burn Day.’ We hold hands and walk around the ashes on the perimeter. We meet back at our camp for pancakes, bacon, eggs, and champagne. And then we reflect upon the week we have experienced on the Playa.”

Leaving the Playa after the burning of the Man on Saturday night and the burning of the Temple on Sunday night is another ritual, known as the Exodus. As a passenger on the Burner Express Bus, I avoided the long lines of waiting to depart because the buses are given priority. However, I had to laugh when boarding the bus to see all of the seats encased in plastic to avoid contamination from Playa Dust. Similarly, the baggage counters at the Reno-Tahoe International Airport are prepared to wrap everything coming from Burning Man in large plastic bags.

I have found that it’s nearly impossible to wash all the Playa Dust out of my clothes, my tent, and everything else I brought with me. Perhaps I can reuse them if I am able to return to Black Rock City next summer, when I might try to collect additional folk genres, such as music, costume, and art. In the meantime, however, I want to keep some of that dust—like many of my Playa memories—with me. Even though Burning Man is intended to be physically ephemeral—returning the Playa to the same condition in which it was found—the values and principles are meant to be taken home and shared in order to spread more widely.

I must admit that returning to a place with a bed and shower has considerable appeal. But I will also always remember what Marshmallow told me, “I get depressed when I leave the Playa because the rest of the world is not as nice as Burning Man.”

James Deutsch is a program curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. His Playa Name is Jean Black—given to him by Mojito Molly because he wears only black jeans, even in the ninety-plus-degree heat of Black Rock City.