Tampon

A tampon is a menstrual product designed to absorb blood and vaginal secretions by insertion into the vagina during menstruation. Unlike a pad, it is placed internally, inside of the vaginal canal.[1] Once inserted correctly, a tampon is held in place by the vagina and expands as it soaks up menstrual blood.

As tampons also absorb the vagina's natural lubrication and bacteria in addition to menstrual blood, they can increase the risk of toxic shock syndrome by changing the normal pH of the vagina and increasing the risk of infections from the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus.[1][2] TSS is a rare but life-threatening infection that requires immediate medical attention.[3]

The majority of tampons sold are made of blends of rayon and cotton, along with synthetic fibers.[4] Some tampons are made out of organic cotton. Tampons are available in several absorbency ratings.

Several countries regulate tampons as medical devices. In the United States, they are considered to be a Class II medical device by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[5] They are sometimes used for hemostasis in surgery.

Design and packaging

[edit]

Tampon design varies between companies and across product lines in order to offer a variety of applicators, materials and absorbencies.[6] There are two main categories of tampons based on the way of insertion – digital tampons inserted by finger, and applicator tampons. Tampon applicators may be made of plastic or cardboard, and are similar in design to a syringe. The applicator consists of two tubes, an "outer", or barrel, and "inner", or plunger. The outer tube has a smooth surface to aid insertion and sometimes comes with a rounded end that is petaled.[7][8]

Differences exist in the way tampons expand when in use: applicator tampons generally expand axially (increase in length), while digital tampons will expand radially (increase in diameter).[9] Most tampons have a cord or string for removal. The majority of tampons sold are made of rayon, or a blend of rayon and cotton. Organic cotton tampons are marketed as 100% cotton, but they may have plastic covering the cotton core.[10] Tampons may also come in scented or unscented varieties.[7]

Absorbency ratings

[edit]

In the US

[edit]Tampons are available in several absorbency ratings, which are consistent across manufacturers in the U.S. These differ in the amount of cotton in each product and are measured based on the amount of fluid they are able to absorb.[11] The absorbency rates required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for manufacturer labeling are listed below:[12]

| Ranges of absorbency in grams | Corresponding term of absorbency |

|---|---|

| 6 and under | Light absorbency |

| 6 to 9 | Regular absorbency |

| 9 to 12 | Super absorbency |

| 12 to 15 | Super plus absorbency |

| 15 to 18 | Ultra absorbency |

| Above 18 | No term |

In Europe

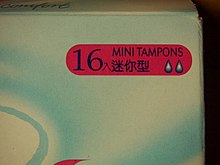

[edit]Absorbency ratings outside the US may be different. The majority of non-US manufacturers use absorbency rating and Code of Practice[13] recommended by EDANA (European Disposables and Nonwovens Association).

| Droplets | Grams | Alternative size description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 droplet | < 6 | |

| 2 droplets | 6–9 | Mini |

| 3 droplets | 9–12 | Regular |

| 4 droplets | 12–15 | Super |

| 5 droplets | 15–18 | |

| 6 droplets | 18–21 |

In the UK

[edit]In the UK, the Absorbent Hygiene Product Manufacturers Association (AHPMA) has written a Tampon Code of Practice which companies can follow on a volunteer basis.[14] According to this code, UK manufacturers should follow the (European) EDANA code (see above).

Testing

[edit]A piece of test equipment referred to as a Syngyna (short for synthetic vagina) is usually used to test absorbency. The machine uses a condom into which the tampon is inserted, and synthetic menstrual fluid is fed into the test chamber.[15]

A novel way of testing was developed by feminist medical experts after the toxic shock syndrome (TSS) crisis, and used blood – rather than the industry standard blue saline – as a test material.[16]

Labeling

[edit]The FDA requires the manufacturer to perform absorbency testing to determine the absorbency rating using the Syngyna method or other methods that are approved by the FDA. The manufacturer is also required to include on the package label the absorbency rating and a comparison to other absorbency ratings as an attempt to help consumers choose the right product and avoid complications of TSS. In addition, The following statement of association between tampons and TSS is required by the FDA to be on the package label as part of the labeling requirements: "Attention: Tampons are associated with Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS). TSS is a rare but serious disease that may cause death. Read and save the enclosed information."[12]

Such guidelines for package labeling are more lenient when it comes to tampons bought from vending machines. For example, tampons sold in vending machines are not required by the FDA to include labeling such as absorbency ratings or information about TSS.[12]

Costs

[edit]The average person who menstruates uses approximately 11,400 tampons in their lifetime, assuming exclusive use of tampons. Tampon prices have risen due to inflation and supply chain challenges. Currently, a box of tampons typically costs between $7 and $12 USD and contains 16 to 40 tampons, depending on the brand and size. This means users might spend between $63 and $108 annually on tampons alone, assuming the need for around 9 boxes per year. This corresponds to an average cost of approximately $0.22–$0.75 per tampon, reflecting price increases of up to 33% since the pandemic [17] [18] Activists call the problem some women have when not being able to afford products "period poverty". Also referred to as "tampon tax," where sales tax applies to menstrual products in certain U.S. states. As of 2024, 23 states exempt these products, while others impose taxes up to 7%. Local taxes can also apply, adding further costs. States like Texas recently abolished this tax. Some states provide free tampons and pads in public schools and prisons, helping alleviate period poverty.[19] [20]

Health aspects

[edit]Toxic shock syndrome

[edit]Menstrual toxic shock syndrome (mTSS) is a life-threatening disease most commonly caused by infection of superantigen-producing Staphylococcus aureus. The superantigen toxin secreted in S. aureus infections is TSS Toxin-1, or TSST-1. Incidence ranges from 0.03 to 0.50 cases per 100,000 people, with an overall mortality around 8%.[21] mTSS signs and symptoms include fever (greater than or equal to 38.9 °C), rash, desquamation, hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg), and multi-system organ involvement with at least three systems, such as gastrointestinal complications (vomiting), central nervous system (CNS) effects (disorientation), and myalgia.[22]

Toxic shock syndrome was named by James K. Todd in 1978.[23] Philip M. Tierno Jr., Director of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology at the NYU Langone Medical Center, helped determine that tampons were behind toxic shock syndrome (TSS) cases in the early 1980s. Tierno blames the introduction of higher-absorbency tampons made with rayon in 1978, as well as the relatively recent decision by manufacturers to recommend that tampons can be worn overnight, for the surge in cases of TSS.[24] However, a later meta-analysis found that the material composition of tampons is not directly correlated to the incidence of toxic shock syndrome, whereas oxygen and carbon dioxide content of menstrual fluid uptake is associated more strongly.[25][26][27]

In 1982, a liability case called Kehm v. Proctor & Gamble took place, where the family of Patricia Kehm sued Procter & Gamble for her death on September 6, 1982, from TSS, while using Rely brand tampons. The case was the first successful case to sue the company. Procter & Gamble paid $300,000 in compensatory damages to the Kehm family. This case can be attributed to the increase in regulations and safety protocol testing for current FDA requirements.[2]

Some risk factors identified for developing TSS include recent labor and delivery, tampon use, recent staphylococcus infection, recent surgery, and foreign objects inside the body.[28]

The FDA suggests the following guidelines for decreasing the risk of contracting TSS when using tampons:[29][30]

- Choose the lowest absorbency needed for one's flow (test of absorbency is approved by FDA)

- Follow package directions and guidelines for insertion and tampon usage (located on box's label)

- Change the tampon at least every 4 to 8 hours

- Alternate usage between tampons and pads

- Increase awareness of the warning signs of Toxic Shock Syndrome and other tampon-associated health risks (and remove the tampon as soon as a risk factor is noticed)

The FDA also advises those with a history of TSS not to use tampons and instead turn to other feminine hygiene products to control menstrual flow.[31] Other menstrual hygiene products available include pads, menstrual cups, menstrual discs, and reusable period underwear.[1]

Cases of tampon-connected TSS are very rare in the United Kingdom[32][33][34] and United States.[35][36] A controversial study by Tierno found that all-cotton tampons were less likely than rayon tampons to produce the conditions in which TSS can grow.[37] This was done using a direct comparison of 20 brands of tampons, including conventional cotton/rayon tampons and 100% organic cotton tampons.[38] In a series of studies conducted after this initial claim, it was shown that all tampons (regardless of composition) are similar in their effect on TSS and that tampons made with rayon do not have an increased incidence of TSS.[21] Instead, tampons should be selected based on minimum absorbency rating necessary to absorb flow corresponding to the individual.[30]

Sea sponges are also marketed as menstrual hygiene products. A 1980 study by the University of Iowa found that commercially sold sea sponges contained harmful materials like sand and bacteria.[39]

Studies have shown non-significantly higher mean levels of mercury in tampon users compared to non tampon users. No evidence showed an association between tampon use and inflammation biomarkers.[40]

Other considerations

[edit]Bleached products

[edit]According to the Women's Environmental Network research briefing on menstrual products made from wood pulp:[41]

The basic ingredient for menstrual pads is wood pulp, which begins life as a brown coloured product. Various 'purification' processes can be used to bleach it white. Measurable levels of dioxin have been found near paper pulping mills, where chlorine has been used to bleach the wood pulp. Dioxin is one of the most persistent and toxic chemicals, and can cause reproductive disorders, damage to the immune system and cancer (26). There are no safe levels and it builds up in our fat tissue and in our environment.

Marine pollution

[edit]In the UK, the Marine Conservation Society has researched the prevalence and problem of plastic tampon applicators found on beaches.[42]

Disposal and flushing

[edit]Disposal of tampons, especially flushing (which manufacturers warn against) may lead to clogged drains and waste management problems.[43]

Tampon-drug interactions

[edit]There are multiple cases in which the use of tampons may need medical advice from a healthcare professional. For example, as part of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Library of Medicine and its branch MedlinePlus advise against using tampons while being treated with any of several medications taken by the vaginal route such as vaginal suppositories and creams, as tampons may decrease the absorbance of these drugs by the body. Example of these medications include clindamycin,[44] terconazole,[45] miconazole,[46] clotrimazole,[47] when used as a vaginal cream or vaginal suppository, as well as butoconazole vaginal cream.[48]

Increased risk for infections

[edit]According to the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), tampons may be responsible for an increased risk of infection due to the erosions it causes in the tissue of the cervix and vagina, leaving the skin prone to infections. Thus, ASBMT advises hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients against using tampons while undergoing therapy.[49]

Other uses

[edit]Clinical use

[edit]Tampons are currently being used and tested to restore and/or maintain the normal microbiota of the vagina to treat bacterial vaginosis.[50] Some of these are available to the public but come with disclaimers.[51] The efficacy of the use of these probiotic tampons has not been established.

Tampons have also been used in cases of tooth extraction to reduce post-extraction bleeding.[52]

Tampons are currently being investigated as a possible use to detect endometrial cancer.[53] Endometrial cancer does not currently have effective cancer screening methods if an individual is not showing symptoms.[54] Tampons not only absorb menstrual blood, but also vaginal fluids. The vaginal fluids absorbed in the tampons would also contain the cancerous DNA, and possibly contain precancerous material, allowing for earlier detection of endometrial cancer.[55] Clinical trials are currently being conducted to evaluate the use of tampons as a screening method for early detection of endometrial cancer.

Environment and waste

[edit]

Appropriate disposal of used tampons is still lacking in many countries. Because the lack of menstrual management practices in some countries, many sanitary pads or other menstrual products will be disposed into domestic solid wastes or garbage bins that eventually becomes part of a solid wastes.[56]

The issue that underlies the governance or implementation of menstrual waste management is how country categorizes menstrual waste. This waste could be considered as a common household waste, hazardous household waste (which will required to be segregated from routine household waste), biomedical waste given amount of blood it contains, or plastic waste given the plastic content in many commercial disposal pads (some only the outer case of the tampon or pads).[57]

Ecological impact varies according to disposal method (whether a tampon is flushed down the toilet or placed in a garbage bin – the latter is the recommended option). Factors such as tampon composition will likewise impact sewage treatment plants or waste processing.[58] The average use of tampons in menstruation may add up to approximately 11,400 tampons in someone's lifetime (if they use only tampons rather than other products).[59] Tampons are made of cotton, rayon, polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, and fiber finishes. Aside from the cotton, rayon and fiber finishes, these materials are not biodegradable. Organic cotton tampons are biodegradable, but must be composted to ensure they break down in a reasonable amount of time. Rayon was found to be more biodegradable than cotton.[60]

Environmentally friendly alternatives to using tampons are the menstrual cup, reusable sanitary pads, menstrual sponges, reusable tampons,[61] and reusable absorbent underwear.[62][63][64]

The Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm carried out a life-cycle assessment (LCA) comparison of the environmental impact of tampons and sanitary pads. They found that the main environmental impact of the products was in fact caused by the processing of raw materials, particularly LDPE (low density polyethylene) – or the plastics used in the backing of pads and tampon applicators, and cellulose production. As production of these plastics requires a lot of energy and creates long-lasting waste, the main impact from the life cycle of these products is fossil fuel use, though the waste produced is significant in its own right.[65]

The menstrual material was disposed according to the type of product, and even based on cultural beliefs. This was done regardless of giving any importance to the location and proper techniques of disposal. In some areas of the world, menstrual waste is disposed into pit latrines, as burning and burial were difficult due to limited private space.[56]

History

[edit]Women have used tampons during menstruation for thousands of years. In her book Everything You Must Know About Tampons (1981), Nancy Friedman writes,[66]

[T]here is evidence of tampon use throughout history in a multitude of cultures. The oldest printed medical document, Ebers Papyrus, refers to the use of soft papyrus tampons by Egyptian women in the fifteenth century B.C. Roman women used wool tampons. Women in ancient Japan fashioned tampons out of paper, held them in place with a bandage, and changed them 10 to 12 times a day. Traditional Hawaiian women used the furry part of a native fern called hapu'u; and grasses, mosses and other plants are still used by women in parts of Asia and Africa.

R. G. Mayne defined a tampon in 1860 as: "a less inelegant term for the plug, whether made up of portions of rag, sponge, or a silk handkerchief, where plugging the vagina is had recourse to in cases of hemorrhage."[67]

Earle Haas patented the first modern tampon, Tampax, with the tube-within-a-tube applicator. Gertrude Schulte Tenderich (née Voss) bought the patent rights to her company trademark Tampax and started as a seller, manufacturer, and spokesperson in 1933.[68] Tenderich hired women to manufacture the item and then hired two sales associates to market the product to drugstores in Colorado and Wyoming, and nurses to give public lectures on the benefits of the creation, and was also instrumental in inducing newspapers to run advertisements.

In 1945, Tampax presented a number of studies to prove the safety of tampons. A 1965 study by the Rock Reproductive Clinic stated that the use of tampons "has no physiological or clinical undesired side effects".[23]

During her study of female anatomy, German gynecologist Judith Esser-Mittag developed a digital-style tampon, which was made to be inserted without an applicator. In the late 1940s, Carl Hahn and Heinz Mittag worked on the mass production of this tampon. Hahn sold his company to Johnson & Johnson in 1974.[69]

In 1992, Congress found an internal FDA memo about the presence of dioxin, a known carcinogen, in tampons.[70] Dioxin is one of the toxic chemicals produced when wood pulp is bleached with chlorine.[71] Congressional hearings were held and tampon manufacturers assured Congress that the trace levels of dioxin in tampons was well below EPA level. The EPA has stated there is no acceptable level of dioxin.[70] Following this, major commercial tampon brands began switching from dioxin-producing chlorine gas bleaching methods to either elemental "chlorine-free" or "totally chlorine free" bleaching processes.[72]

In the United States, the Tampon Safety and Research Act was introduced to Congress in 1997 in an attempt to create transparency between tampon manufacturers and consumers. The bill would mandate the conduct or support of research on the extent to which additives in feminine hygiene products pose any risks to the health of women or to the children of women who use those products during or before the pregnancies involved.[73] Although yet to be passed, the bill has been continually reintroduced, most recently in 2019 as the Robin Danielson Feminine Hygiene Product Safety Act.[74] Data would also be required from manufacturers regarding the presence of dioxins, synthetic fibers, chlorine, and other components (including contaminants and substances used as fragrances, colorants, dyes, and preservatives) in their feminine hygiene products.

Society and culture

[edit]Tampon tax

[edit]"Tampon tax" refers to tampons' lack of tax exempt status that is often in place for other basic need products. Several political statements have been made in regards to tampon use. In 2000, a 10% goods and services tax (GST) was introduced in Australia. While lubricant, condoms, incontinence pads and numerous medical items were regarded as essential and exempt from the tax, tampons continue to be charged GST. Prior to the introduction of GST, several states also applied a luxury tax to tampons at a higher rate than GST. Specific petitions such as "Axe the Tampon Tax" have been created to oppose this tax, and the tax was removed in 2019.[75] In the UK, tampons are subject to a zero rate of value added tax (VAT), as opposed to the standard rate of 20% applied to the vast majority of products sold in the country.[76] The UK was previously bound by the EU VAT directive, which required a minimum of 5% VAT on sanitary products. Since 1 January 2021, VAT applied to menstrual sanitary products has been 0%.

In Canada, the federal government has removed the goods and services tax (GST) and harmonized sales tax (HST) from tampons and other menstrual hygiene products as of 1 July 2015.[77]

In the US, access to menstrual products such as pads and tampons and taxes added on these products, have also been controversial topics especially when it comes to people with low income.[78] Laws for exempting such taxes differ vastly from state to state.[78] The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has published a report discussing these laws and listing the different guidelines followed by institutions such as schools, shelters, and prisons when providing menstrual goods.[78]

The report by ACLU also discusses the case of Kimberly Haven who was a former prisoner that had a hysterectomy after she had experienced toxic shock syndrome (TSS) due to using handmade tampons from toilet paper in prison.[79][78] Her testimony supported a Maryland bill that is intended to increase access of menstrual products for imprisoned women.[78]

Etymology

[edit]Historically, the word "tampon" originated from the medieval French word "tampion", meaning a piece of cloth to stop a hole, a stamp, plug, or stopper.[80]

Virginity

[edit]There is a misconception described as sexist[81][82] that using a tampon rids a person of their virginity. This is because some cultures regard virginity as indicated by whether the hymen is still intact, and may believe that inserting a tampon breaks the hymen. However, this belief is not rooted in medical science. The hymen, a thin membrane partially covering the vaginal opening, varies greatly in thickness, elasticity, and shape from person to person. It almost never blocks the entire vaginal opening, stretches and thins naturally over time, and can stretch or break due to non-sexual everyday activities such as exercise;[83][84] conversely, it may not break even after penetrative sexual intercourse, as it is able to stretch.[85] Therefore, the presence or condition of the hymen is not an indicator of virginity.

Medical professionals have pointed out that misconceptions about the hymen lead to medically unfounded and harmful practices such as virginity testing and hymenoplasty.[86]

In popular culture

[edit]In Stephen King's novel Carrie, the title character is bullied for menstruating and is bombarded with tampons and pads by her peers.

In 1985, Tampon Applicator Creative Klubs International (TACKI) was established to develop creative uses for discarded, non-biodegradable, plastic feminine hygiene products, commonly referred to as "beach whistles". TACKI President Jay Critchley launched his corporation in order to develop a global folk art movement and cottage industry, promote awareness of these throwaway objects washed up on beaches worldwide from faulty sewage systems, create the world's largest collection of discarded plastic tampon applicators, and ban their manufacture and sale through legislative action. The project and artwork was carried out during numerous site-specific performances and installations.[87]

Intersectionality

[edit]Gender Inclusion

[edit]Tampons are traditionally marketed as products for women, conserving the idea that menstruation only affects cisgender women, or women who were assigned female at birth and continue to identify with that label. This framing marginalizes transgender men, nonbinary individuals, and genderqueer people who menstruate. This makes their experiences with menstruation largely invisible in public discourse, marketing, and product design. Addressing gender inclusion in the context of tampons involves examining societal stigmas, access challenges, and evolving efforts to create more inclusive spaces for all people who menstruate. In recent years, when discussing periods, academia has shifted terminology to be more inclusive, thus beginning to use the term "menstruators" instead of "women."[88]

Additionally, public restrooms often reinforce a binary understanding of gender. Men’s restrooms rarely, if ever, provide menstrual product dispensers, leaving many queer people without access to tampons when needed.[89] When using the women's bathroom in attempt to have access to period products, transgender and nonbinary individuals may face safety concerns or harassment for accessing restrooms that align with their gender identity.

Some menstrual product companies, such as Aunt Flow and Thinx, have started using inclusive language like “menstrual products” instead of “feminine hygiene products.” These efforts aim to normalize menstruation for all individuals who experience it, regardless of gender. In marketing, efforts to redesign tampon packaging to be more gender-neutral help make these products less alienating for trans and nonbinary users. [90] Removing pink or floral designs, for example, makes them more approachable.

Socioeconomic Disparities

[edit]Access to tampons is shaped by significant socioeconomic disparities, with systemic barriers disproportionately affecting individuals from low-income backgrounds. These disparities show up in various ways, including affordability challenges, stigmatization, and inadequate infrastructure.[91] Addressing these issues requires recognizing how economic inequality intersects with social factors to restrict access to menstrual products like tampons.

A large issue in our society is period poverty, which refers to the lack of access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, and education due to financial constraints. It is a prevalent issue in both developing and developed countries, where many people cannot afford tampons and other menstrual products. In many low-income communities, individuals often miss school, work, or social activities due to a lack of menstrual products. This contributes to cycles of poverty, as menstruation becomes a barrier to education and economic opportunities.[92] Globally, an estimated 500 million people face period poverty. In United States, studies have shown that one in five students have struggled to afford menstrual products.[93]

Many schools, shelters, and prisons fail to provide tampons for free or in sufficient quantities.[94] Low-income students, in particular, may resort to unsafe alternatives like paper towels or rags, which can lead to health risks such as infections. Homeless menstruators face unique challenges, as they often lack both the financial means to purchase tampons and access to clean facilities for changing them.[95] Nonprofits like The Homeless Period Project work to distribute tampons to these populations, but systemic support is still lacking.

Racial Inequities

[edit]Racial inequities in access to menstrual products are shaped by a complex interplay of systemic racism, socioeconomic disparities, cultural stigmas, and healthcare inequality. These inequities disproportionately affect menstruators from marginalized backgrounds, limiting their access to essential products.

Menstruators from racialized communities are more likely to live in poverty due to historical economic inequities. This economic disadvantage makes purchasing tampons and other menstrual products a financial burden.[96] This is because in some predominantly Black and Brown communities, menstrual products may be sold at higher prices due to fewer retail options and the "poverty tax," where essential goods cost more in underserved areas.

Cultural stigmas around menstruation can be particularly pronounced in certain racial and ethnic communities, where periods may be considered taboo or inappropriate to discuss openly.[97] This silence can discourage menstruators from seeking tampons or advocating for their needs. In some cultures, tampons are viewed with suspicion. They are linked to myths about virginity or seen as inappropriate for younger menstruators. These beliefs can limit the willingness or ability of individuals in certain racial groups to access tampons.

Additionally, schools in marginalized racial communities often lack comprehensive menstrual education programs. This lack of education can leave menstruators unaware of the variety of menstrual products available, or unsure how to use them safely. On top of that, racial biases in the education system may contribute to a lack of attention to the menstrual health needs of students from different racial groups.[98]

There are many other aspects of racial inequity when it comes to menstrual product education and accessibility. People of color are less likely to have access to adequate gynecological care, and more likely to face discrimination in the health world regardless of their health issue. To add onto that, the diverse needs of people from ethnic backgrounds have historically been neglected by marketing companies.[99] When advertising does attempt to include people of color, it often fails to address the unique cultural stigmas, challenges, or values that shape their experiences with menstruation.

Tampons and Disability

[edit]Individuals with conditions that affect fine motor skills or hand strength (e.g., arthritis, cerebral palsy, or multiple sclerosis) may find it difficult to unwrap, insert, or remove tampons.[100] The small size of tampons and their applicators can be a significant barrier. Most tampons are designed with the assumption of able-bodied users, lacking features like ergonomic grips, adaptive applicators, or designs that accommodate reduced hand mobility. Public restrooms, especially those not compliant with accessibility standards, may not provide sufficient space or the necessary support structures (e.g., grab bars) for disabled individuals to manage tampon insertion or removal. People who struggle with vision may encounter difficulties identifying tampon sizes, brands, or instructions due to the lack of braille on packaging or tactile features on the products themselves. For menstruators with hearing impairments, they may miss out on important product usage information if it is only provided through audio formats or poorly captioned content.

People with intellectual or developmental disabilities may require additional support to learn how to use tampons safely and effectively. Complex instructions, such as proper insertion angles and removal timing, can be challenging to navigate without guidance. Caregivers or support workers may need to assist disabled menstruators with tampon usage. However, this raises concerns about autonomy, privacy, and dignity, as menstruation is a deeply personal experience.

Certain disabilities or chronic illnesses (e.g., endometriosis, pelvic floor disorders, or interstitial cystitis) may make tampon use uncomfortable or painful. These conditions can limit access to tampons as a viable option for menstrual care. Some disabled individuals have heightened sensitivity to tampon materials (e.g., rayon, chlorine bleach, or fragrances), which can increase discomfort or lead to allergic reactions.

Disabled menstruators often face compounded stigma, as society tends to marginalize both disabled individuals and discussions around menstruation.[101] This can lead to isolation and discomfort in seeking out appropriate menstrual products.

Activism and Advocacy

[edit]Advocacy around tampons intersects with broader movements for menstrual equity. These movements aim to dismantle the societal, economic, and cultural barriers that perpetuate inequality. Activism plays a critical role in shaping policy and ensuring that tampons are accessible and affordable for all menstruators. Many advocacy groups campaign to remove sales tax on tampons and other menstrual products, arguing that these items are essential healthcare products rather than luxury goods.[102] Success stories include states and countries that have already abolished the tax, setting a precedent for global change.[103]

Campaigns also work to normalize conversations about menstruation, dismantling stigma that has historically silenced discussions around menstrual products. Destigmatization efforts include public education campaigns, art installations, and social media movements aimed at reframing menstruation as a natural aspect of human health.[104] Advocates are pushing for the portrayal of menstruation in mainstream media, emphasizing diverse menstruators’ experiences and highlighting the role of tampons in empowering individuals to manage their periods effectively.

Organizations like Period: The Menstrual Movement and Menstrual Equity for All are working to raise awareness about the need for inclusivity in menstruation-related discussions. Advocating for free menstrual products in schools, prisons, and public spaces, particularly in areas serving predominantly racialized populations, can help bridge gaps in access. Schools and healthcare providers must offer menstrual care that reflect the cultural challenges faced by diverse racial groups, ensuring that tampons are accessible to all.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Period Products: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". UT Health Austin. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ a b Vostral, Sharra L. (December 2011). "Rely and Toxic Shock Syndrome: A Technological Health Crisis". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 84 (4): 447–459. ISSN 0044-0086. PMC 3238331. PMID 22180682.

- ^ "Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)". Saint Luke's Health System. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ Nadia Kounang (13 November 2015). "What's in your pad or tampon?". CNN. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ "Product Classification". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ "Tampons". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b "Using Tampons: Facts And Myths". SteadyHealth. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Lynda Madaras (8 June 2007). What's Happening to My Body? Book for Girls: Revised Edition. Newmarket Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-55704-768-7.

- ^ "Pain While Inserting A Tampon". Steadyhealth.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "What Are Organic Tampons and Are They Worth Buying?". Consumer Reports. 2024-07-08. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ "Tampon Absorbency Ratings - Which Tampon is Right for You". Pms.about.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ "Edana Code of Practice for tampons placed on the European market" (PDF). EDANA. September 2020.

- ^ "Tampon Code of Practice". AHPMA. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.ahpma.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-07. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Vostral, Sharra (2017-05-23). "Toxic shock syndrome, tampons and laboratory standard–setting". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 189 (20): E726–E728. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161479. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 5436965. PMID 28536130.

- ^ "It's not just you: Tampons are harder to find — and pricier". 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Cost of Having Your Period in Every Country and U.S. State".

- ^ "What is the "tampon tax"?".

- ^ "Tampon Tax: An Additional Economic Burden for Those Who Menstruate: Women's Health Education Program Blog". 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Berger, Selina; Kunerl, Anika; Wasmuth, Stefan; Tierno, Philip; Wagner, Karoline; Brügger, Jan (September 2019). "Menstrual toxic shock syndrome: case report and systematic review of the literature". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (9): e313–e321. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30041-6. ISSN 1474-4457. PMID 31151811. S2CID 172138016.

- ^ "Toxic Shock Syndrome (Other Than Streptococcal) | 2011 Case Definition". wwwn.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ a b Delaney, Janice; Lupton, Mary Jane; Toth, Emily (1988). The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252014529.

- ^ "A new generation faces toxic shock syndrome". The Seattle Times. January 26, 2005.

- ^ Lanes, Stephan F.; Rothman, Kenneth J. (1990). "Tampon absorbency, composition and oxygen content and risk of toxic shock syndrome". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 43 (12): 1379–1385. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(90)90105-X. ISSN 0895-4356. PMID 2254775.

- ^ Ross, R. A.; Onderdonk, A. B. (2000). "Production of Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin 1 by Staphylococcus aureus Requires Both Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide". Infection and Immunity. 68 (9): 5205–5209. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.9.5205-5209.2000. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 101779. PMID 10948145.

- ^ Schlievert, Patrick M.; Davis, Catherine C. (2020-05-27). "Device-Associated Menstrual Toxic Shock Syndrome". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 33 (3): e00032–19, /cmr/33/3/CMR.00032–19.atom. doi:10.1128/CMR.00032-19. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 7254860. PMID 32461307.

- ^ "Toxic shock syndrome: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "e-CFR: Title 21: Food and Drugs Administration". Code of Federal Regulations. Section 801.430: User labeling for menstrual tampons: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Commissioner, Office of the (2019-02-09). "The Facts on Tampons—and How to Use Them Safely". FDA.

- ^ "Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Kent, Ellie (2019-02-07). "I nearly died from toxic shock syndrome and never used a tampon". BBC Three. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ "TSS: Continuing Professional Development". Toxic Shock Syndrome Information Service. 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ Mosanya, Lola (2017-02-14). "Recognising the symptoms of toxic shock syndrome saved my life". BBC Newsbeat. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ "Toxic Shock Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015-02-11. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ "What You Need To Know About Toxic Shock Syndrome". University of Utah Health. 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- ^ Tierno, Philip M.; Hanna, Bruce A. (1985-02-01). "Amplification of Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin-1 by Intravaginal Devices". Contraception. 31 (2): 185–194. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(85)90033-2. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 3987281.

- ^ Tierno, Philip M.; Hanna, Bruce A. (1998-03-01). "Viscose Rayon versus Cotton Tampons". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 177 (3): 824–825. doi:10.1086/517804. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 9498476.

- ^ Affairs, Office of Regulatory (2021-05-05). "CPG Sec. 345.300 Menstrual Sponges". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ Singh, Jessica; Mumford, Sunni L.; Pollack, Anna Z.; Schisterman, Enrique F.; Weisskopf, Marc G.; Navas-Acien, Ana; Kioumourtzoglou, Marianthi-Anna (11 February 2019). "Tampon use, environmental chemicals and oxidative stress in the BioCycle study". Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source. 18 (1): 11. Bibcode:2019EnvHe..18...11S. doi:10.1186/s12940-019-0452-z. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 6371574. PMID 30744632.

- ^ "Seeing Red: Menstruation & The Environment" (PDF) (Report). Women's Environmental Network. 2018.

- ^ O'Neill, Erin (28 August 2019). "Campaigning for plastic-free periods". Marine Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020.

- ^ Agencies NA of CW. International Water Industry Position Statement on non-flushable and flushable labelledproducts. 2016; Available from:https://www.nacwa.org/docs/default-source/resources---public/2016-11-29wipesposition3dd68e567b5865518798ff0000de1666.pdf

- ^ "Clindamycin Vaginal: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Terconazole Vaginal Cream, Vaginal Suppositories: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Miconazole Vaginal: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Clotrimazole Vaginal: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Butoconazole Vaginal Cream: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Guidelines for Preventing Opportunistic Infections Among Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ Zespoł Ekspertów Polskiego Towarzystwa Ginekologicznego (2012). "Statement of the Polish Gynecological Society Expert Group on the use of ellen probiotic tampon". Ginekol. Pol. (in Polish). 83 (8): 633–8. PMID 23342891.

- ^ "Markets absorbed by probiotic Swedish tampons". The Local. 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ^ Kalantar Motamedi, M H; Navi, F; Shams Koushki, E; Rouhipour, R; Jafari, S M (June 2012). "Hemostatic Tampon to Reduce Bleeding following Tooth Extraction". Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 14 (6): 386–388. ISSN 2074-1804. PMC 3420033. PMID 22924121.

- ^ Fiegl, Heidi; Gattringer, Conny; Widschwendter, Andreas; Schneitter, Alois; Ramoni, Angela; Sarlay, Daniela; Gaugg, Inge; Goebel, Georg; Müller, Hannes M.; Mueller-Holzner, Elisabeth; Marth, Christian (2004-05-01). "Methylated DNA Collected by Tampons—A New Tool to Detect Endometrial Cancer". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 13 (5): 882–888. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.882.13.5. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 15159323. S2CID 6352434.

- ^ Matteson, Kristen A.; Robison, Katina; Jacoby, Vanessa L. (2018-09-01). "Opportunities for Early Detection of Endometrial Cancer in Women With Postmenopausal Bleeding". JAMA Internal Medicine. 178 (9): 1222–1223. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2819. ISSN 2168-6106. PMID 30083765. S2CID 51928791.

- ^ "Women's Wellness: Tampon test for endometrial cancer". 14 December 2016. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ a b Kaur, Rajanbir; Kaur, Kanwaljit; Kaur, Rajinder (2018-02-20). "Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries". Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2018: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2018/1730964. ISSN 1687-9805. PMC 5838436. PMID 29675047.

- ^ Elledge, Myles F.; Muralidharan, Arundati; Parker, Alison; Ravndal, Kristin T.; Siddiqui, Mariam; Toolaram, Anju P.; Woodward, Katherine P. (November 2018). "Menstrual Hygiene Management and Waste Disposal in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Review of the Literature". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (11): 2562. doi:10.3390/ijerph15112562. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 6266558. PMID 30445767.

- ^ Rastogi, Nina (2010-03-16). "What's the environmental impact of my period?". Slate.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Nicole, Wendee (March 2014). "A Question for Women's Health: Chemicals in Feminine Hygiene Products and Personal Lubricants". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (3): A70–5. doi:10.1289/ehp.122-A70. PMC 3948026. PMID 24583634.

- ^ Park, Chung Hee; Kang, Yun Kyung; Im, Seung Soon (2004-09-15). "Biodegradability of cellulose fabrics". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 94 (1): 248–253. doi:10.1002/app.20879. ISSN 1097-4628.

- ^ "How Reusable Tampons Work". Elite Daily.

- ^ Sanghani, Radhika (3 June 2015). "Period nappies: The only new sanitary product in 45 years. Seriously - Telegraph". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ Kirstie McCrum (4 June 2015). "Could 'period-proof pants' spell the end for tampons and sanitary towels?". mirror.

- ^ Spinks, Rosie (2015-04-27). "Disposable tampons aren't sustainable, but do women want to talk about it?". the Guardian.

- ^ "The Environmental Impact of Everyday Things". The Chic Ecologist. 2010-04-05.

- ^ Who invented tampons? 6 June 2006, The Straight Dope

- ^ Mayne, R. G. (1860). An Expository Lexicon of the Terms, Ancient and Modern, in Medical and General Science including a Complete Medico-Legal Vocabulary. London: John Churchill. p. 1249.

- ^ "The History of Tampax". tampax.com. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Johnson & Johnson History". Funding Universe. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b Houppert, Karen (1999). The Curse (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. pp. 18–21. ISBN 0374273669.

- ^ Sharma, Nirmal; Bhardwaj, Nishi K.; Singh, Ram Bhushan Prashad (2020-05-20). "Environmental issues of pulp bleaching and prospects of peracetic acid pulp bleaching: A review". Journal of Cleaner Production. 256: 120338. Bibcode:2020JCPro.25620338S. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120338. ISSN 0959-6526. S2CID 214154074.

- ^ Bobel, Chris (2006-11-02). ""Our Revolution Has Style": Contemporary Menstrual Product Activists "Doing Feminism" in the Third Wave". Sex Roles. 54 (5–6): 331–345. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9001-7. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 17610463.

- ^ Maloney, Carolyn B. (1997-11-14). "H.R.2900 - 105th Congress (1997-1998): Tampon Safety and Research Act of 1997". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ Maloney, Carolyn B. (2019-07-22). "Text - H.R.3865 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Robin Danielson Feminine Hygiene Product Safety Act of 2019". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ "The tampon tax is gone: what now?". Kin Fertility. Australia.

- ^ "Tampon Tax Abolished From Today". HM Treasury. 2021-01-01. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ "Federal government taking the tax off tampons and other feminine hygiene products, effective July 1". National Post. 2015-05-28. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e "The Unequal Price of Periods". American Civil Liberties Union. November 2019. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "No tampons in prison? #MeToo helps shine light on issue". AP NEWS. 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "Oxford Languages | The Home of Language Data". languages.oup.com.

- ^ van Brunnersum, Sou-Jie (15 October 2019). "Asia's tampon taboo – DW – 10/15/2019". dw.com. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ "Using Tampons | How To Put In A Tampon Correctly". The Mix. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ "Debunking 10 Major Myths about Tampons". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ "Hymen: Overview, Function & Anatomy". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Mishori, R; Ferdowsian, H; Naimer, K; Volpellier, M; McHale, T (3 June 2019). "The little tissue that couldn't - dispelling myths about the Hymen's role in determining sexual history and assault". Reproductive Health. 16 (1): 74. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0731-8. PMC 6547601. PMID 31159818.

Ultimately, evaluation of the hymen tissue, if visible, in and of itself, without supportive history, physical examination, or other forensic findings, could never answer the question of whether an individual – child or adult – had consensual or nonconsensual sex.

- ^ Moussaoui, Dehlia; Abdulcadir, Jasmine; Yaron, Michal (March 2022). "Hymen and virginity: What every paediatrician should know". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 58 (3): 382–387. doi:10.1111/jpc.15887. PMC 9306936. PMID 35000235.

- ^ "TACKI - Tampon Application Creative Klubs International". Jay Critchley. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Babbar, Karan; Martin, Jennifer; Varanasi, Pratyusha; Avendano, Ivett (March 20, 2023). "Inclusion means everyone: standing up for transgender and non-binary individuals who menstruate worldwide". The Lancet Regional Health. Southeast Asia. 13. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100177. PMC 10305890. PMID 37383557.

- ^ Frank, Sarah E. (2020). "Queering Menstruation: Trans and Non-Binary Identity and Body Politics". Sociological Inquiry. 90 (2): 371–404. doi:10.1111/soin.12355. ISSN 1475-682X.

- ^ Cozac, Ioana-Mihaela (2024-06-18). "With Great Product Comes Great Responsibility: Marketing Gender and Eco-Responsibility". Journal of the Austrian Association for American Studies. 5 (2): 269–77. doi:10.47060/jaaas.v5i2.189. ISSN 2616-9533.

- ^ Michel, Janet; Mettler, Annette; Schönenberger, Silvia; Gunz, Daniela (2022-02-22). "Period poverty: why it should be everybody's business". Journal of Global Health Reports. 6: e2022009. doi:10.29392/001c.32436.

- ^ Rossouw, Laura; Ross, Hana (January 2021). "Understanding Period Poverty: Socio-Economic Inequalities in Menstrual Hygiene Management in Eight Low- and Middle-Income Countries". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (5): 2571. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052571. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7967348. PMID 33806590.

- ^ Magazine, Harvard Public Health; Burtka, Allison Torres (2023-06-12). ""It's a dignity issue": Inside the movement tackling period poverty in the U.S." Harvard Public Health Magazine. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ O'Shea Carney, Mitchell (2020). "Cycles of Punishment: The Constitutionality of Restricting Access to Menstrual Health Products in Prisons". Boston College Law Review. 61: 2541.

- ^ DeMaria, Andrea L.; Martinez, Rebecca; Otten, Emily; Schnolis, Emma; Hrubiak, Sofia; Frank, Jaclyn; Cromer, Risa; Ruiz, Yumary; Rodriguez, Natalia M. (2024-03-27). "Menstruating while homeless: navigating access to products, spaces, and services". BMC Public Health. 24 (1): 909. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-18379-z. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 10976832. PMID 38539114.

- ^ Damle, Karuna; Riley, Jaz (2023-11-30). "Period poverty's impact on the futures of its most marginalized groups: How the upward mobility of women and girls in the US is influenced by period poverty". Journal of Student Research. 12 (4). doi:10.47611/jsrhs.v12i4.5877. ISSN 2167-1907.

- ^ Montgomery, Rita E. (1974). "A Cross-Cultural Study of Menstruation, Menstrual Taboos, and Related Social Variables". Ethos. 2 (2): 137–170. doi:10.1525/eth.1974.2.2.02a00030. ISSN 0091-2131. JSTOR 639905.

- ^ Martinez, L. Virginia (2020-05-01). Racial Injustices: The Menstrual Health Experiences of African American and Latina Women (Thesis thesis).

- ^ Francis, June N.P. (2022-01-01). "Rescuing marketing from its colonial roots: a decolonial anti-racist agenda". Journal of Consumer Marketing. 40 (5): 558–570. doi:10.1108/JCM-07-2021-4752. ISSN 0736-3761.

- ^ Wilbur, Jane; Torondel, Belen; Hameed, Shaffa; Mahon, Thérèse; Kuper, Hannah (2019-02-06). "Systematic review of menstrual hygiene management requirements, its barriers and strategies for disabled people". PLOS ONE. 14 (2): e0210974. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1410974W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210974. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6365059. PMID 30726254.

- ^ Sibel, Caynak; Zeynep, Ozer; Ilkay, Keser (2022). "Stigma for disabled individuals and their family: A systematic review". EBSCO. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ Crays, Allyson (2023). "Limitations of Current Menstrual Equity Advocacy and a Path Towards Justice". UCLA Journal of Gender and Law. 30 (1). doi:10.5070/L330161547.

- ^ Fox, Susan (2020-09-19). "Advocating for Affordability: The Story of Menstrual Hygiene Product Tax Advocacy in Four Countries". Gates Open Res. 4 (134): 134. doi:10.21955/gatesopenres.1116669.1.

- ^ Olson, Mary M.; Alhelou, Nay; Kavattur, Purvaja S.; Rountree, Lillian; Winkler, Inga T. (2022-07-14). "The persistent power of stigma: A critical review of policy initiatives to break the menstrual silence and advance menstrual literacy". PLOS Global Public Health. 2 (7): e0000070. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0000070. ISSN 2767-3375. PMC 10021325. PMID 36962272.

External links

[edit]- Myths About Tampons (web article)

- Original patent by Earle Haas

- Tampon Related Patents (archived)

- Can Tampons Cause a UTI by TamponsAndMenstrualCups.com

- ^ Magarey, Susan (2014), "The tampon", Dangerous Ideas, Women’s Liberation – Women’s Studies – Around the World, University of Adelaide Press, pp. 147–158, doi:10.20851/j.ctt1t305d7.14?searchtext=magarey,+susan.+"the+tampon."&searchuri=/action/dobasicsearch?query=magarey,+susan.+“the+tampon.”&so=rel&ab_segments=0/basic_phrase_search/control&refreqid=fastly-default:71c77770f797e413d95bcea0eb5258d6&seq=5 (inactive 2024-11-28), ISBN 978-1-922064-94-3, JSTOR 10.20851/j.ctt1t305d7.14, retrieved 2024-11-21

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)