Sonny Greer

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2010) |

Sonny Greer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | William Alexander Greer |

| Born | December 13, 1895 Long Branch, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | March 23, 1982 (aged 86) New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation | Musician |

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1910–1966 |

| Formerly of | Elmer Snowden, Duke Ellington, Washingtonians |

William Alexander "Sonny" Greer (December 13, c. 1895 – March 23, 1982)[1] was an American jazz drummer and vocalist, best known for his work with Duke Ellington.

Early Life and Career

[edit]Greer was born in Long Branch, New Jersey. There has been long-standing confusion about his birth year since he tried to maintain a youthful image in the public eye, but his birth year ranges from 1895 to 1904.[2] Greer lived in Asbury Park, New Jersey as a child with his father, an electrician with the Pennsylvania Road, and mother, a modiste, and his younger brother and sister. As a child, he worked many side jobs as a caddy, fish peddler, and newspaper deliverer.[3]

Greer started getting into music and taught himself how to sing and drum with the help of only one mentor, drummer Eugene “Peggy” Holland, who played with composer, J. Rosamond Johnson for two weeks.[3] The vaudeville drummer gave him a few lessons but also advice not just with music, but also with life as a man and how one should carry himself.[2]

Greer started his career in his mid-teens when he began playing at resort hotels along the Jersey Shore with local orchestras. After a performance in the Plaza Hotel, he received an invitation to appear in Washington, D.C. with the Howard Theatre where he played for three years until he met Duke Ellington. Greer was balancing his commitments with Ellington and the Howard Theatre until the mid-1920s when he worked exclusively with Ellington.[4]

Ellington Years

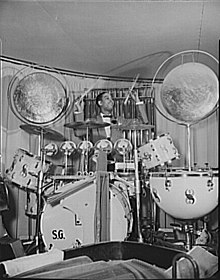

[edit]Greer was Ellington's first drummer, playing with his quintet, the Washingtonians, and moved with Ellington into the Cotton Club.[1] As a result of his job as a designer with the Leedy Drum Company of Indiana, Greer was able to build up a huge drum kit worth over a then-considerable $3,000, including chimes, a gong, timpani, and vibes.[5]

Greer was constantly on tour with the Ellington Orchestra and was there for its rise to fame in the 1930s and 1940s. Greer took the spotlight during the performances as the organization of his drum set drew the audience’s eyes.[4] Music critic for the New York Times, John S. Wilson, wrote that Greer was “enthroned on a stand on which he was surrounded by a glittering array of paraphernalia."[6] Wilson continues to write that this included instruments such as chimes, tom-toms, snare drums, bass drums, and a gong that was “set up in back of him as though to form a massive halo.”[6]

Greer was a substantial contributor to the Ellington Orchestra. Trombonist, Lawrence Brown, states that when he joined the band in 1932, it became clear to him how important of a contributor Greer was. Brown states, “He was almost as popular as Ellington. Not only did he have excellent musical instincts and natural ability as a player, he was very genial and served as contact man for Duke.”[2] Brown continues to say that Greer got to be knowledgeable about music by simply “performing and absorbing what was happening around him.”[2] Mercer Ellington, the son of Duke, states that Greer “was one of the few people from whom Ellington readily took advice” from and that he had a “great ear and unusual reflexes.”[2]

Even with the orchestra’s and Greer’s achievements, Greer had his hardships with Ellington due to his heavy drinking, but he was able to let his habits leave his talent and skill unaffected for years. He did have occasions where his performance was affected by his drinking, but Ellington was able to keep him on track until the late 1940s and early 1950s when his performance significantly worsened.[4] In 1950, Ellington responded to his drinking and occasional unreliability by taking a second drummer, Butch Ballard, with them on a tour of Scandinavia.[1] This decision and his behavior eventually progressed to his dismissal from the Ellington Orchestra in 1951.[2]

Late Career

[edit]After his firing from the Ellington Orchestra, Greer appeared in a group of a former Ellington saxophonist, Jonny Hodges.[4] He stayed in the band for some time and helped create the albums Castle Rock (Norgan, 1955) and Creamy (Norgan, 1955). After his work with Hodges, Greer began to work many short-term engagements with many collaborators in New York City, such as Red Allen, J. C. Higginbotham, and Tyree Glenn.[4]

Greer featured in the 1958 black-and-white photograph by Art Kane known as "A Great Day in Harlem". He was part of a tribute to Ellington in 1974, which achieved great success throughout the United States. Greer even led his own trio, but he nearly always focused on live performance after his collaborations. His only exception during this period was his work with Brooks Kerr and saxophonist Russel Procope. Greer helped him complete the Soda Fountain Rag: The Music of Duke Ellington album in 1975.[4] After Procope’s death, the two men still continued to play.[3]

Personal Life and Death

[edit]Greer was married for over 50 years to his wife Millicent, who was a Cotton Club dancer. They had a daughter, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great grandchildren.[3]

Greer continued to play in New York jazz clubs until he reached his 70s where he was forced to stop as he was diagnosed with cancer.[4] This disease led him to his eventual death at the time St. Luke’s Hospital, Manhattan, New York on March 23, 1982. His funeral service was held on March 28, 1982, at St. Peter’s Church and he was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.[6]

Discography

[edit]With Duke Ellington

- Duke Ellington (RCA Victor, 1957)

- The Duke in London (Decca, 1957)

- At the Cotton Club (RCA Camden, 1958)

- Caravan (RCA Victor, 1958)

- Jazz Cocktail (Columbia, 1958)

- Johnny Come Lately (RCA Victor, 1967)

- The Duke Elington Carnegie Hall Concerts, January 1943 (Prestige, 1977)

With Johnny Hodges

- Castle Rock (Norgran, 1955)

- Creamy (Norgran, 1955)

With others

- Bernard Addison, High in a Basement (77 Records, 1961)

- Louis Armstrong, Town Hall (RCA Victor, 1957)

- Earl Hines, Once Upon a Time (Impulse!, 1966)

- Lionel Hampton, Lionel Hampton (RCA Victor, 1958)

- Lonnie Johnson, Playing with the Strings (JSP, 2004)

- Brooks Kerr, Soda Fountain Rag (Chiaroscuro, 1974)

- Oscar Pettiford, Oscar Rides Again (Proper, 2008)

- Rex Stewart, Cootie Williams, Tea and Trumpets (His Master's Voice, 1955)

- Victoria Spivey, The Queen and Her Knights (Spivey, 1965)

- Josh White, Sings Ballads, Blues (Elektra, 1957)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. 174. ISBN 0-85112-580-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Korall, Burt. "Other Major Figures." Drummin' Men: The Heartbeat of Jazz The Swing Years. Oxford University Press, 1st ed., 2002, Oxford Academic, pp. 305-332.

- ^ a b c d Balliet, Whitney. "Sonny Greer" The New Yorker, 12 April 1982, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1982/04/12/sonny-greer. Accessed 12 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kugler. "Sonny Greer 1903(?)-1982." Contemporary Black Biography, edited by Margaret Mazukiewicz, vol. 127, Gale, 2016, Gale EBooks, pp. 38-40

- ^ "Drummerworld: Sonny Greer". Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ^ a b c Wilson, John S. (1982-03-25). "SONNY GREER, 78, ELLINGTON DRUMMER, IS DEAD". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-12-12.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ian Carr, Digby Fairweather & Brian Priestley. Jazz: The Rough Guide. ISBN 1-85828-528-3

External links

[edit]- Sonny Greer — brief biography by Scott Yanow, for Allmusic (also contains a discography)

- Sonny Greer at Drummerworld.com

- Sonny Greer at IMDb

- Sonny Greer recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.