Tourism in Thailand

This article needs to be updated. (May 2022) |

Tourism is an economic contributor to the Kingdom of Thailand. Estimates of tourism revenue directly contributing to the GDP of 12 trillion baht range from one trillion baht (2013) 2.53 trillion baht (2016), the equivalent of 9% to 17.7% of GDP.[1][2] When including indirect travel and tourism receipts, the 2014 total is estimated to be the equivalent of 19.3% (2.3 trillion baht) of Thailand's GDP.[3]: 1 According to the secretary-general of the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council in 2019, projections indicate the tourism sector will account for 30% of GDP by 2030, up from 20% in 2019, Thailand expects to receive 80 million visitors in 2027. [4]

Tourism worldwide in 2017 accounted for 10.4% of global GDP and 313 million jobs, or 9.9% of total employment.[5]: 1 Most governments view tourism as an easy moneymaker and a shortcut to economic development. Tourism success is measured by the number of visitors.[6]

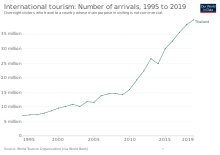

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand was ranked the world’s eighth most visited country by World Tourism rankings compiled by the United Nations World Tourism Organization. In 2019, Thailand received 39.8 million international tourists, ahead of United Kingdom and Germany.[7] and received fourth highest international tourism earning at 60.5 billion US dollar.

The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT), a state enterprise under the Ministry of Tourism and Sports, uses the slogan "Amazing Thailand" to promote Thailand internationally.[8] In 2015, this was supplemented by a "Discover Thainess" campaign.[9]

Overview

[edit]

Among the reasons for the increase in tourism in the 1960s were the stable political atmosphere and the development of Bangkok as a crossroads of international air transport.[10] The hotel industry and retail industry both expanded rapidly due to tourist demand. It was boosted by the presence of US GIs who arrived in the 1960s for rest and recuperation (R&R) during the Vietnam War.[11] During this time, international tourism was becoming the new trend as living standards increased throughout the world and travel became faster and more dependable with the introduction of new technology in the air transport sector.[12]

Tourist numbers have grown from 336,000 foreign visitors and 54,000 GIs on R&R in 1967[11] to 32.59 million foreign guests visiting Thailand in 2016.[13][14][15] The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) claims that the tourist industry earned 2.52 trillion baht (US$71.4 billion) in 2016, up 11% from 2015.[13] TAT officials said their revenue estimates, for foreign and domestic tourists combined, show that tourism revenue for all of 2017 may surpass earlier forecasts of 2.77 trillion baht (US$78.5 billion).[13]

In 2015, 6.7 million people arrived from ASEAN countries and the number is expected to grow to 8.3 million in 2016, generating 245 billion baht.[16] The largest numbers of Western tourists came from Russia (6.5%), the UK (3.7%), Australia (3.4%) and the US (3.1%).[17] Around 60% of Thailand's tourists are return visitors.[18]

In 2014, 4.6 million Chinese visitors travelled to Thailand.[17][19] In 2015, Chinese tourists numbered 7.9 million or 27% of all international tourist arrivals, 29.8 million; 8.75 million Chinese tourists visited Thailand in 2016.[20][16] In 2017, 27% of the tourists that came to Thailand came from China.[21] Thailand relies heavily on Chinese tourists to meet its tourism revenue target of 2.2 trillion baht in 2015 and 2.3 trillion in 2016. However, in 2020, it was reported that Chinese tourists now ranked Thailand as third most popular foreign tourist destination, having been the top previously.[22]

It is estimated that the average Chinese tourist remains in the country for one week and spends 30,000–40,000 baht (US$1,000–1,300) per person, per trip.[23] The average Chinese tourist spends 6,400 baht (US$180) per day—more than the average visitor's 5,690 baht (US$160).[16][19] According to Thailand's Tourism Authority, the number of Chinese tourists rose by 93% in the first quarter of 2013, an increase that was attributed to the popularity of the Chinese film Lost in Thailand that was filmed in the northern province of Chiang Mai. Chinese media outlets have claimed that Thailand superseded Hong Kong as the top destination for Chinese travellers during the 2013 May Day holiday.[24] In 2013, the Chinese National Tourism Administration published A Guide to Civilized Tourism which has specific statements regarding how to act as a tourist in Thailand.[25]

In 2015, Thailand hosted 1.43 million Japanese travellers, up 4.1% from 2015, generating 61.4 billion baht, up 6.3%. In 2016, Thailand expects 1.7 million Japanese tourists, generating 66.2 billion baht in revenue.[26]

TAT estimates that 1.9 million Indian tourists visited in 2019, up 22% from 2018, generating 84 billion baht in revenue, up 27%.[27]

To accommodate foreign visitors, the Thai government established a separate tourism police force with offices in the major tourist areas and its own central emergency telephone number.[28]

Since the opening of the Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos borders in the late 1900s, competition has increased because Thailand no longer has the monopoly on tourism in Southeast Asia.[29] Destinations like Angkor Wat, Luang Prabang and Halong Bay now rival Thailand's former monopoly in the Indochina region. To counter this, Thailand is targeting niche markets such as golf holidays, holidays combined with medical treatment or visits to military installations.[20] Thailand has also plans to become the hub of Buddhist tourism in the region.[30]

International rankings

[edit]In 2008, Pattaya was 23rd with 4,406,300 visitors, Phuket 31st with 3,344,700 visitors, and Chiang Mai ranked 78th place with 1,604,600 visitors.[31]

In a list released by Instagram that identified the ten most photographed locations worldwide in 2012, Suvarnabhumi Airport and Siam Paragon shopping mall were ranked number one and two respectively, more popular than New York City's Times Square or Paris's Eiffel Tower.[32]

In 2013, Thailand was the 10th "top tourist destination" in the world tourism rankings with 26.5 million international arrivals.[33]: 6

In the MasterCard 2014 and 2015 Global Destination Cities Index, Bangkok ranked the second of the world's top-20 most-visited cities, trailing only London.[34][35] The U.S. News' 2017 Best Countries report ranked Thailand at 4th globally for adventure value and 7th for cultural heritage.[36]

The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015 published by the World Economic Forum ranked Thailand 35 of 141 nations. Among the metrics used to arrive at the rankings, Thailand scored high on "Natural Resources" (16 of 141 nations) and "Tourist Service Infrastructure" (21 of 141), but low on "Environmental Sustainability" (116 of 141) and "Safety and Security" (132 of 141).[37][38]

In 2016, Bangkok ranked 1st surpassing London and New York in Euromonitor International's list of "Top City Destinations" with 21 million visitors.

In 2019, Bangkok ranked 1st surpassing Paris and London in Mastercard's list of "Global Destination Cities Index 2019" with 22.78 million visitors. Phuket was 14th with 9.89 million visitors and Pattaya 15th with 9.44 million visitors.[39]

-

Phuket ranked 14th with 9.89 million visitors

-

Pattaya ranked 15th with 9.44 million visitors

-

Chiang Mai with 6.38 million visitors [40]

Impact of political unrest

[edit]At the commencement of 2014, the Thai tourist industry suffered due to the political turmoil that erupted in October 2013. A shutdown of Bangkok's governmental offices on 13 January 2014 by anti-government protesters, prompted some tourists to avoid the Thai capital. TAT estimated that arrival numbers might drop by around five percent in the first quarter of 2014, with the total number of arrivals down by 260,000 from the original projection of 29.86 million. Tourism revenue is also expected to drop slightly from 1.44 trillion.[41]

Tourist arrivals in 2014 totalled 24.7 million, a drop of 6.6% from 2013. Revenues derived from tourism amounted to 1.13 trillion baht, down 5.8% from the previous year. Kobkarn Wattanavarangkul, Thailand's Minister of Tourism and Sports, attributed the decline to the political crisis in the first half of 2014 which dissuaded many potential visitors from visiting Thailand. Tourism officials also pointed to the dramatic fall in the value of the Russian ruble which has damaged the economies of popular Russian destinations such as Phuket and Pattaya.[42]

At the beginning of April 2015, Thailand ended martial law, to be replaced by Article 44 of the provisional constitution, granting unrestricted powers to the prime minister. The words "martial law" were toxic to foreign democracies, but, in terms of tourism, even more toxic to foreign travel insurance providers, who decline to provide insurance to those visiting nations under martial law. The tourism industry rebounded swiftly after the lifting of martial law. Deputy Prime Minister Pridiyathorn Devakula said that the arrival of high-spending tourists from Europe and the US is expected to increase.[43]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

Statistics

[edit]Foreign tourist arrivals in Thailand

[edit]| Country | 9/2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,254,764 | 3,521,095 | 273,567 | 13,043 | 1,251,498 | 10,997,338 | 10,535,241 | 9,806,260 | 8,757,646 | 7,936,795 | 4,636,298 | 4,637,335 | 2,786,860 | |

| 3,742,474 | 4,626,422 | 1,948,549 | 5,511 | 619,623 | 4,265,574 | 4,020,526 | 3,494,488 | 3,494,890 | 3,418,855 | 2,613,418 | 3,041,097 | 2,554,397 | |

| 1,536,196 | 1,628,542 | 997,913 | 6,544 | 263,659 | 1,996,842 | 1,598,346 | 1,415,197 | 1,194,508 | 1,069,422 | 932,603 | 1,050,889 | 1,013,308 | |

| 1,382,785 | 1,660,042 | 538,766 | 12,077 | 262,017 | 1,890,973 | 1,796,426 | 1,709,265 | 1,464,200 | 1,373,045 | 1,122,566 | 1,295,342 | 1,163,619 | |

| 1,159,758 | 1,482,611 | 435,008 | 30,759 | 590,151 | 1,483,337 | 1,472,789 | 1,346,338 | 1,090,083 | 884,136 | 1,606,430 | 1,746,565 | 1,316,564 | |

| 899,576 | 919,401 | 502,124 | 733 | 380,207 | 1,854,792 | 1,664,630 | 1,682,087 | 1,388,020 | 1,220,522 | 1,053,983 | 976,639 | 975,999 | |

| 813,255 | 724,594 | 94,834 | 1,675 | 117,511 | 790,039 | 687,748 | 573,077 | 522,273 | 552,699 | 394,149 | 502,176 | 394,225 | |

| 786,032 | 1,033,688 | 468,393 | 1,794 | 132,127 | 1,048,181 | 1,028,150 | 935,179 | 830,220 | 751,162 | 559,415 | 725,057 | 618,670 | |

| 762,648 | 805,768 | 290,146 | 9,461 | 322,677 | 1,806,438 | 1,656,101 | 1,544,442 | 1,439,510 | 1,381,702 | 1,267,886 | 1,536,425 | 1,373,716 | |

| 707,104 | 930,206 | 453,678 | 37,880 | 212,669 | 1,165,950 | 1,122,270 | 1,056,423 | 975,643 | 867,505 | 763,520 | 823,486 | 768,638 | |

| 697,886 | 1,027,424 | 614,627 | 5,931 | 126,771 | 1,059,484 | 1,069,867 | 1,032,647 | 967,550 | 938,385 | 844,133 | 955,468 | 831,215 | |

| 666,859 | 817,220 | 444,432 | 38,663 | 223,087 | 992,574 | 986,854 | 994,755 | 1,004,345 | 947,568 | 907,877 | 905,024 | 873,053 | |

| 665,174 | 802,368 | 162,240 | 1,657 | 124,518 | 1,045,361 | 1,015,749 | 821,064 | 751,264 | 669,617 | 483,131 | 588,335 | 473,666 | |

| 648,650 | 762,118 | 235,632 | 2,577 | 99,530 | 710,494 | 644,709 | 576,110 | 534,797 | 469,125 | 497,592 | 594,251 | 447,820 | |

| 588,298 | 729,163 | 365,030 | 45,874 | 231,782 | 852,481 | 886,523 | 850,139 | 837,885 | 761,819 | 715,240 | 737,658 | 682,419 | |

| 544,569 | 687,745 | 336,688 | 9,577 | 123,827 | 767,291 | 801,203 | 817,218 | 796,370 | 807,450 | 831,854 | 900,460 | 930,241 | |

| 515,228 | 545,003 | 268,587 | 23,461 | 237,317 | 745,346 | 749,556 | 740,190 | 738,878 | 681,114 | 635,073 | 611,582 | 576,106 | |

| 420,812 | 461,251 | 178,021 | 4,078 | 72,762 | 506,430 | 432,237 | 381,252 | 339,150 | 310,968 | 304,813 | 321,571 | 289,566 | |

| 414,920 | 583,708 | 379,665 | 4,914 | 165,027 | 910,696 | 948,824 | 840,871 | 674,975 | 537,950 | 550,339 | 481,595 | 423,642 | |

| 399,548 | 394,134 | 193,778 | 7,256 | 55,279 | 378,232 | 368,188 | 365,606 | 341,626 | 259,678 | 206,794 | 172,383 | 129,385 | |

| 194,091 | 217,084 | 146,293 | 14,038 | 29,444 | 195,856 | 188,788 | 173,673 | 161,579 | 141,031 | 138,778 | 134,874 | 129,551 | |

| 190,840 | 229,539 | 116,354 | 8,539 | 52,402 | 241,608 | 236,265 | 222,409 | 235,762 | 221,619 | 211,524 | 218,765 | 208,122 | |

| 181,425 | 191,983 | 85,254 | 5,322 | 60,602 | 272,374 | 279,905 | 264,524 | 265,597 | 246,094 | 219,875 | 207,192 | 200,703 | |

| 172,575 | 178,113 | 96,389 | 467 | 4,227 | 30,006 | 28,337 | 33,531 | 24,834 | 19,168 | 12,860 | 21,452 | 17,084 | |

| 172,521 | 214,264 | 90,608 | 6,440 | 58,499 | 273,214 | 276,094 | 258,494 | 244,869 | 227,601 | 211,059 | 229,897 | 219,354 | |

| 146,525 | 153,458 | 87,400 | 3,514 | 25,904 | 188,997 | 181,880 | 179,584 | 168,900 | 150,995 | 116,983 | 123,084 | 113,141 | |

| 136,235 | 138,934 | 65,857 | 4,061 | 7,492 | 130,158 | 128,270 | 137,218 | 130,941 | 124,719 | 117,907 | 123,926 | 113,547 | |

| 130,531 | 172,489 | ||||||||||||

| 130,138 | 178,259 | 97,378 | 17,094 | 111,994 | 287,341 | 311,949 | 323,736 | 332,895 | 321,690 | 324,865 | 341,398 | 364,681 | |

| 122,139 | 156,337 | 81,180 | 11,429 | 52,361 | 192,130 | 207,471 | 209,528 | 209,057 | 206,480 | 201,271 | 199,923 | 191,147 | |

| 112,440 | 121,700 | ||||||||||||

| 102,640 | 140,657 | 81,106 | 1,955 | 21,838 | 136,677 | 129,574 | 121,765 | 100,263 | 107,394 | 88,134 | 82,418 | 72,657 | |

| 98,248 | 115,224 | 64,249 | 8,480 | 66,848 | 162,456 | 169,373 | 161,920 | 165,581 | 159,435 | 160,977 | 163,186 | 167,499 | |

| 75,244 | 85,512 | 48,684 | 5,386 | 26,394 | 114,669 | 114,270 | 112,266 | 111,013 | 106,090 | 99,729 | 101,109 | 94,896 | |

| 74,018 | 88,706 | 42,683 | 5,486 | 36,381 | 111,428 | 116,656 | 104,784 | 100,373 | 97,869 | 100,968 | 106,278 | 94,667 | |

| 73,939 | 83,952 | 46,521 | 5,763 | 39,778 | 127,992 | 128,841 | 127,850 | 131,039 | 135,382 | 145,207 | 154,049 | 148,796 | |

| 68,612 | 85,897 | 35,900 | 1,151 | 15,709 | 112,680 | 116,726 | 117,962 | 111,595 | 112,411 | 108,081 | 118,395 | 113,871 | |

| 55,481 | 76,193 | 38,561 | 6,139 | 59,567 | 128,014 | 140,961 | 140,464 | 134,238 | 134,750 | 142,425 | 141,692 | 154,919 | |

| Total | 26,088,855 | 28,150,016 | 11,153,026 | 427,869 | 6,725,193 | 39,916,251 | 38,178,194 | 35,591,978 | 32,529,588 | 29,923,185 | 24,809,683 | 26,546,725 | 22,353,903 |

Past tourism statistics

[edit]| Year | Arrivals | % change |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 28,042,131 | |

| 2022 | 11,153,026 | |

| 2021 | 819,429 | |

| 2020 | 6,702,396 | |

| 2019 | 39,797,406 | |

| 2018 | 38,277,300 | |

| 2017 | 35,381,210 | |

| 2016 | 32,588,303 | |

| 2015 | 29,881,091 | |

| 2014 | 24,809,683 | |

| 2013 | 26,546,725 | |

| 2012 | 22,353,903 | |

| 2011 | 19,230,470 | |

| 2010 | 15,936,400 | |

| 2009 | 14,149,841 | |

| 2008 | 14,584,220 | |

| 2007 | 14,464,228 | |

| 2006 | 13,821,802 | |

| 2005 | 11,516,936 |

In their justifications for constructing a new coal-fired power plant in Krabi Province (2015), the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) presumes that by 2032 Thailand will receive more than 100 million tourists a year, 40% of them visiting Phuket and neighbouring areas such as Krabi. On average, the power consumption of a tourist is four times higher than that of a local resident.[52]

In 2015 some segments of Thailand's hospitality industry enjoyed their best year in over two decades, according to research firm STR Global. Thailand closed the year with an overall hotel occupancy of 73.4%, an increase of 13.6% over 2014, as arrivals rose to near the 30 million mark, driven by demand from the Chinese market. December 2015 was a particularly strong month as occupancy levels reached 77.4%, the highest level since 1995.[53]

Despite the increasing number of tourist arrivals, some businesses catering to the tourist trade report declining numbers. Mr Sompoch Sukkaew, chief legal counsel of the Patong Entertainment Business Association (PEBA) in Phuket, said in January 2016 that entertainment businesses are suffering. "Over the past three years, most bars were averaging about B90,000 revenue per day at this time of year,...now they're making just B40,000. Small bars...used to average B40,000 to B50,000 a day, now they're down to just B10,000 per day....PEBA members generated about B1.5 million per day during the peak season. Now it's down to about B540,000 per day." PEBA members number 500 in Patong, with about 200 businesses in the Bangla Road entertainment area. PEBA President Weerawit Kuresombat attributed the decline to the rise in Chinese tourism. "...most of them [Chinese tourists] come on complete tour packages....This means they spend very little on extras....They rarely venture out for the nightlife or even visit independent restaurants. They just don't spend much", he said.[54]

The Thai government expects revenue from foreign tourists to increase by 8.5% to 1.78 trillion baht (US$49.8 billion) in 2017. Deputy Prime Minister Thanasak Patimaprakorn attributed the increase to the improving outlook for global tourism as well as Thailand's investments in infrastructure. In 2016, Thailand had 32.6 million visitors, a rise of nearly nine percent from 2015. In 2017 the number of tourists visiting Thailand exceeded 35 million.[55] Thanasak expects daily tourist spending to increase to 5,200 baht per person in 2017, up from 5,100 baht in 2016.[51] Local tourists are expected to contribute an additional 950 billion baht in tourism revenues in 2017.[56]

According to the Ministry of Tourism and Sports (MOTS, Citation2021a) and the National Statistical Office of Thailand (Citation2016), the number of international tourists that visited Thailand climbed significantly from 9.51 million in 2000 to 39.92 million in 2019. Meanwhile, inbound tourism revenue climbed gradually from USD 9,500 million to USD 63,727 million, representing an almost 700% rise.[57]

Sex tourism

[edit]Kobkarn Wattanavrangkul, named Thailand's first female tourism minister in 2014, has pledged to eradicate Thailand's sex industry. "We want Thailand to be about quality tourism. We want the sex industry gone," Ms Kobkarn told Reuters. "Tourists don't come to Thailand for sex. They come here for our beautiful culture." She has named Pattaya, with its thousands of bars, brothels, and massage parlours, her "pilot project" in the cleanup campaign.[58] Kobkarn was replaced as tourism minister in November 2017.[59]

On 21 February 2017, Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha announced that he will order the police to dismantle Pattaya's sex industry. "I don't support prostitution", said Prayut.[60]

Medical tourism

[edit]As of 2019[update], with 64 accredited hospitals, Thailand is currently among the top 10 medical tourism destinations in the world. In 2017, Thailand registered 3.3 million visits by foreigners seeking specialised medical treatment. In 2018, this number grew to 3.5 million.[61][62] As of 2019[update] Thai medical centres are serving increasing numbers of Chinese medical tourists in tandem with increasing overall Chinese tourism.[63] All numbers reported by the government must be viewed with some skepticism according to the authors of a 2010 study.[which?] The Thai government reported that in 2006, 1.2 million medical tourists were treated in Thailand. But the 2010 study of five private hospitals that serve more than 60% of foreign medical tourists concluded that there were 167,000 medical tourists in Thailand in 2010, far below the government estimate. Most came for minor elective (cosmetic) surgery.[62]

Gastronomical tourism

[edit]The governor of the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT), said the agency aims to increase income from the gastronomy business from 20% of total tourism income forecasted for 2017 to 25% in 2018. In 2017, TAT aims for 2.77 trillion baht in tourism revenue, 20% of which is projected to come from gastronomy. In 2018, tourism revenue is expected to climb to three trillion baht, with gastronomy accounting for 750 billion baht. Thailand's 103,000 street food vendors alone generated 270 billion baht in revenues in 2017. Suvit Maesincee, Minister of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, expects the Thai street food segment to grow by six to seven percent annually.[64]

TAT, in early-2017, approved a budget of 144 million baht to commission the Michelin Guide to rate restaurants in Thailand for the five-year period 2017–2021. The first guide, Michelin Guide to Bangkok, was released on 6 December 2017. It bestowed Michelin stars on 17 Bangkok restaurants, ten of which do not serve Thai food.[65] Guides to other cities will follow.

In 2016, gastronomy was Thailand's fourth-largest tranche (20%) of tourism income, after accommodation (29%), transport (27%), and shopping and souvenirs (24%). TAT estimates that Chinese tourists spent 83.3 billion baht on food in Thailand in 2016, followed by Russians at 20.8 billion baht, Britons at 18.4 billion baht, Malaysians at 16.1 billion baht, and Americans at 13.9 billion baht.[66]

Elephant tourism

[edit]Elephant trekking has been an attraction for tourists in Thailand for decades. Ever since logging in Thailand was banned in 1989, elephants were brought into camps to put on shows for tourists and to give them rides. The majority of these elephants once used to work in the logging industry. After the government banned logging,[67] many mahouts were then unable to care for their elephants and left them in the wild. After tourism in the country rose, elephants came back into demand. The tourism boom gave elephants a place to work and be cared for. Today there are an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 domesticated elephants in the country.[68]

However, concerns were raised regarding their welfare. Elephants can sustain injuries related to giving rides, or going on treks, with tourists. The elephant's spine is curved and not optimised to carry heavy loads—the weight of two or more tourists at a time. The chairs or benches often used for the tourists to sit on upon it can also cause abrasions and chafing on its back, sides, and torso. During treks mahouts control the elephants with hooks and can use excessive force, resulting in puncture wounds.[68] Common training practices include being chained, cut, stabbed, burned and hit to varying degrees. Inexperienced mahouts are more likely to further harm their elephants and beat them into submission.[68] Hooks are the common tool used to discipline and guide an elephant during treks.[67]

Sport tourism

[edit]

Muay Thai is the national sport of Thailand, and a trip to a stadium to witness the 'science of the eight limbs' is an essential experience for many tourists.[69] Studying Muay Thai is a main activity for Thai sport tourism, which the government promotes.[70]

In 2016, there were 11,219 British people, 6,800 Australians, and 5,852 French nationals who visited Thailand to take lessons in the classical martial art. Thirty-eight percent of all people signing up for Muay Thai classes chose Phuket as their study destination, 28% chose Bangkok, and 16% chose Surat Thani.[71]

Tourism authority and initiatives

[edit]In order to reignite growth in Thailand's tourist industry, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) has embarked on a new campaign for 2015 entitled "2015: Discover Thainess".[9][72] TAT Governor Thawatchai Arunyik said the campaign will incorporate the "twelve values" that Thai junta leader and Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha wants all Thais to practice.[42] TAT officials foresee a large increase in tourist numbers due to the "Discover Thainess" campaign. Ms Somrudi Chanchai, Director of the TAT Northeastern Office, has forecasted that tourists to her Isan region will increase by 27.9 million [sic] visitors, generating 65 billion baht in revenue.[73]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

Safety concerns

[edit]Thailand has problems of ensuring adequate safety for foreign tourists, as there were many cases of murder.[74] The high profile Koh Tao murders in 2014 gained the island the nickname "Death Island".[75]

See also

[edit]- Visa policy of Thailand

- Tourism in Bangkok

- Markets in Bangkok

- Responsible Tourism in Thailand

- List of shopping malls in Thailand

- List of Thai dishes

- Banana Pancake Trail

- MICE in Thailand

References

[edit]- ^ Theparat, Chatrudee (17 February 2017). "Tourism to continue growth spurt in 2017". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Government moves to head off tourist fears". Bangkok Post. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Turner, Rochelle (2015). Travel & Tourism, Economic Impact 2015, Thailand (PDF). London: World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Theparat, Chatrudee (19 September 2019). "Prayut: Zones vital for growth". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ Global Travel & Tourism Economic Impact World 2018 (PDF). London: World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). March 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (2 December 2017). "Only governments can stem the tide of tourism sweeping the globe". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, December 2020 | World Tourism Organization". UNWTO World Tourism Barometer (English Version). 18 (7): 1–36. 18 December 2020. doi:10.18111/wtobarometereng.2020.18.1.7. S2CID 241989515.

- ^ Battle, Velma (5 May 2022). "Quick View Into Thailand Tourism And The Thailand Tourism Organization".

- ^ a b "History". TATnews.org. Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "How Thailand Became a Tourist Hotspot during the 60's". Bloomberg (Video). Thailand Business News. 30 August 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ a b Ouyyanont, Porphant (2001). "The Vietnam War and Tourism in Bangkok's Development, 1960–70" (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies. 39 (2): 157–187.

- ^ Fuller, Ed. "Thailand: The Land Of Smiles Is Still Smiling After All These Years". Forbes. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Record 32.59 Million Foreign Tourists Visit Thailand in 2016". Voice of America. Associated Press. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Tore, Ozgur (23 December 2015). "Thailand greets 29 millionth visitor in 2015". FTN News. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ^ "Thailand hoping to attract wealthier travellers". The Nation. 25 December 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Chinmaneevong, Chadamas (3 March 2016). "TAT aims to attract rich Chinese tourists". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b "International Tourist Arrivals to Thailand 2014 (by nationality)". Department of Tourism (Thailand). Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Tourism in Thailand". Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Chinese tourists boost Thai economy but stir outrage". The Nation. 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ a b "TAT to lure Chinese tourists with military facilities". Bangkok Post. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Thailand Tourism Statistics. Tourist Arrivals from 2000 till 2017. Influence of Epidemics, Political Events (Military Coup), Floods, Economic Downturn on Tourist Arrivals". www.thaiwebsites.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Thailand no longer top overseas destination for Chinese tourists". Bangkok Post. Bloomberg News. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Wanwisa Ngamsangchaikit (18 February 2013). "Chinese spend more in Thailand". TTR Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Julie Zhu (3 May 2013). "Chinese tourists flock to Thailand thanks to hit comedy film". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Guide to Civilised Tourism" (PDF). whiterabbitcollection.org. September 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Suchiva, Nanat (21 February 2017). "Ministry seeks to court more Japanese women". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ Worrachaddejchai, Dusida (8 January 2020). "TAT eagerly awaits Indian tourist surge". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Tourist Police in Thailand Archived 3 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Amazing-Thailand.com. Retrieved on 16 September 2010.

- ^ "Tourism industry in Thailand | MMH In Asia Master Class in Bangkok". blogs.cornell.edu. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Phuket Itinerary | Big Buddha, Phuket Night Markets & Bangla Road". Wanderlust Storytellers | Family Travel Blog. 19 August 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Euromonitor International (January 2010). "Euromonitor International's Top City Destination Ranking". Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Jon Russell (28 December 2012). "Suvarnabhumi Airport in Thailand tops Instagram's list of most photographed places in 2012". The Next Web. The Next Web, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "UNWTO Tourism Highlights". UNWTO (2014 ed.). Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Hedrick-Wong, Yuwa; Choong, Desmond (2014). MasterCard 2014 Global Destination Cities Index. MasterCard. p. 3.

- ^ Hedrick-Wong, Yuwa; Choong, Desmond (2015). "MasterCard 2015 Global Destination Cities Index" (PDF). MasterCard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Best Countries 2017" (PDF). US News. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021.

- ^ The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015. Geneva: World Economic Forum (WEF). 2015. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-92-95044-48-7. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Poor safety record limits Thailand in world tourism rankings". Bangkok Post. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Global Destination Cities Index 2019" (PDF).

- ^ Worrachaddejchai, Dusida (7 October 2019). "Chiang Mai braced for barren hotels". Bangkok Post.

- ^ Amnatcharoenrit, Bamrung (4 January 2014). "Tourist help centres to be set up across the city ahead of shutdown". The Nation. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ a b "2014 Tourist Arrivals in Thailand Drop By 6.6 Percent". Khaosod English. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Tourism rebounds after martial law ended". ThaiVisa. 5 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "สถิตินักท่องเที่ยว Visitor Statistics, 1998–2016". Department of Tourism Thailand (in Thai). Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "สถิติด้านการท่องเที่ยว ปี 2560 (Tourism Statistics 2017)". Ministry of Tourism & Sports. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "International Tourist Arrivals to Thailand (2018)". Ministry of Tourism & Sports. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "สถิตินักท่องเที่ยวชาวต่างชาติที่เดินทางเข้าประเทศไทย ( International Tourist Arrivals to Thailand)". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ a b "สถิตินักท่องเที่ยวชาวต่างชาติที่เดินทางเข้าประเทศไทย ( International Tourist Arrivals to Thailand)". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "สถิติด้านการท่องเที่ยว ปี 2563 (Tourism Statistics 2020)". Ministry of Tourism & Sports. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "สถิติด้านการท่องเที่ยว ปี 2562 (Tourism Statistics 2019)". Ministry of Tourism & Sports. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ a b Hariraksapitak, Pracha; Temphairojana, Pairat (9 January 2017). "Thailand expects tourism revenue of nearly $50 billion in 2017". Reuters. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Future of Krabi's power plant unclear". Bangkok Post. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ "Thailand's hotel occupancy hits 20-year high". eTN Global Travel Industry News. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Sakoot, Tanyaluk (22 January 2016). "Going Down: Businesses on Phuket's famed Bangla Rd suffer as clientele dries up". Phuket News. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Thailand celebrates New Year with 35 million visitors in 2017 – Tourism". Thailand Business News. 2 January 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Flash floods rain down on holidays". Bangkok Post. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Fakfare, Pipatpong; Lee, Jin-Soo; Han, Heesup (12 February 2022). "Thailand tourism: a systematic review". Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 39 (2): 188–214. doi:10.1080/10548408.2022.2061674. hdl:10397/94014. ISSN 1054-8408.

- ^ Marszal, Andrew (17 July 2016). "'Thailand is closed to sex trade', says country's first female tourism minister". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Hamdi, Raini (28 November 2017). "A familiar face helms Thai tourism but Kobkarn will be missed". TTG Asia. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Junta to purge Pattaya of prostitution". Prachatai English. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ Otage, Stephen (12 February 2019). "Uganda: What Uganda Can Learn From Thailand's Medical Tourism". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ a b Noree, Thinakorn; Hanefeld, Johanna; Smith, Richard (2016). "Medical tourism in Thailand: a cross-sectional study" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 94 (1): 30–36. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.152165 (inactive 1 December 2024). PMC 4709795. PMID 26769994. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Luythong, Chettayakhom (9 July 2018). "Healthy Outlook". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Hutasingh, Onnucha (17 February 2020). "Smart food cart to aid gastronomic tourism". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Pandey, Umesh (10 December 2017). "Michelin guide leaves sour taste". Editorial. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Sritama, Suchat (29 November 2017). "Michelin Guide set to hit Thai tables". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b Chatkupt, Thomas T; Aollod, Albert E; Sarobol, Sinth (1999). "Elephants in Thailand: Determinants of Health and Welfare in Working Populations". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 2 (3): 187–203. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0203_2. PMID 16363921.

- ^ a b c Kontogeorgopoulos, Nick (2009). "The Role of Tourism in Elephant Welfare in Northern Thailand" (PDF). Journal of Tourism. 10 (2). Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "A tourist's guide to watching Muay Thai in Thailand". travelwireasia.com. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Tourism and Sports Ministry to support Muay Thai training for foreigners". thephuketnews. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Muay thai tourism by the numbers". nationmultimedia. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "2015 Discover Thainess". Amazing Thailand. Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "More tourists travel "Isan"". National News Bureau of Thailand (NNT). NNT. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "The shame of Thai tourism". Bangkok Post. 7 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Paddock, Richard C.; Suhartono, Muktita (3 November 2018). "Thai Paradise Gains Reputation as 'Death Island'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

External links

[edit]- Tourism Authority of Thailand

- Thailand Tourism Directory

- Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT)

- Ministry of Tourism and Sports

- Thailand Now

- Thailand Convention & Exhibition Bureau (TCEB)

- Thailand Tourism Updates

![Chiang Mai with 6.38 million visitors [40]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dc/%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%81%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%82%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%A5%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%87%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%8A%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A7_%E0%B9%83%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%8A%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%B2.jpg/170px-%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%81%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%82%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%A5%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%87%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%8A%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A7_%E0%B9%83%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%8A%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%B2.jpg)