Lysanias

Lysanias /laɪˈseɪniəs/ was the ruler of a small realm on the western slopes of Mount Hermon, mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus and in coins from c. 40 BC. There is also mention of a Lysanias in Luke's Gospel.

Lysanias in Josephus

[edit]Lysanias was the ruler of a tetrarchy, centered on the town of Abila. This has been referred to by various names including Abilene, Chalcis and Iturea, from about 40-36 BC. Josephus is our main source for his life.

The father of Lysanias was Ptolemy, son of Mennaeus, who ruled the tetrarchy before him. Ptolemy was married to Alexandra, one of the sisters of Antigonus,[1] and he helped his brother-in-law during the latter's successful attempt to claim the throne of Judea in 40 BC with the military support of the Parthians. Ptolemy had previously supported Antigonus's unsuccessful attempt to take the throne of Judea in 42 BC.

Josephus says in The Jewish War that Lysanias offered the Parthian satrap Barzapharnes a thousand talents and 500 women to bring Antigonus back and raise him to the throne, after deposing Hyrcanus[2] though in his later work, the Jewish Antiquities, he says the offer was made by Antigonus.[3] In 33 BC Lysanias was put to death by Mark Antony for his Parthian sympathies, at the instigation of Cleopatra, who had eyes on his territories.[4]

Coins from his reign indicate that he was "tetrarch and high priest". The same description can be found on the coins of his father, Ptolemy son of Mennaeus and on those of his son Zenodorus who held the territory in 23–20 BC.[5]

Lysanias in Luke

[edit]Luke 3:1 mentions a Lysanias (Greek: Λυσανίας) as tetrarch of Abilene in the time of John the Baptist.[6]

According to Josephus the emperor Claudius in 42 AD confirmed Agrippa I in the possession of Abila of Lysanias already bestowed upon him by Caligula, elsewhere described as Abila, which had formed the tetrarchy of Lysanias:[6]

- "He added to it the kingdom of Lysanias, and that province of Abilene"[7]

Archaeological Lysanias

[edit]

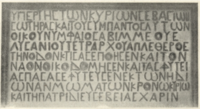

Two inscriptions have been ascribed to Lysanias.[8] The name is conjectural in the latter case.[citation needed]

The first, a temple inscription found at Abila, named Lysanias as the Tetrarch of the locality.[9]

The temple inscription reads:

| Inscription | Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| Huper tes ton kurion Se[baston] | For the salvation of the Au[gust] lords | |

| soterias kai tou sum[pantos] | and of [all] their household, | |

| auton oikou, Numphaios Ae[tou] | Nymphaeus, free[dman] of Ea[gle] | |

| Lusianiou tetrarchou apele[utheors] | Lysanias tetrarch established | |

| ten odon ktisas k.t.l | this street and other things. |

It has been thought that the reference to August lords as a joint title was given only to the emperor Tiberius (adopted son of Augustus) and his mother Livia (widow of Augustus).[10] If this analysis is correct, this reference would establish the date of the inscription to between 14 AD (when Tiberius began to reign) and 29 AD (when Livia died), and thus could not be reasonably interpreted as referring to the ruler executed by Mark Antony in 36 BC. However, Livia received suitable honors while Augustus was still alive, such as "Benefactor Goddess" (Θεα Εύεργέτις) at a temple at Thassos,[11] so there would be no clear reason that "August Lords" could not be Augustus and Livia.

Possible identity of the two figures

[edit]The reference to Lysanias in Luke 3:1, dated to the fifteenth year of Tiberius, has caused some debate over whether this Lysanias is the same person son of Ptolemy, or some different person.

Some say that the Lysanias whose tetrarchy was given to Agrippa cannot be the Lysanias executed by Antony, since his paternal inheritance, even allowing for some curtailment by Pompey, must have been of far greater extent.[6] Therefore, the Lysanias in Luke (28–29) is a younger Lysanias, tetrarch of Abilene only, one of the districts into which the original kingdom was split up after the death of Lysanias I. This younger Lysanias may have been a son of the latter, and identical with, or the father of, the Claudian Lysanias.[6]

But Josephus does not refer to a second Lysanias. It is therefore suggested by others[6] that he really does refer to the original Lysanias, even though the latter died decades earlier. In The Jewish War Josephus refers to the realm as being "called the kingdom of Lysanias",[12] while Ptolemy writing c. 120 in his Geography Bk 5 refers to Abila as "called of Lysanias"[13]

The explanation given by M. Krenkel (Josephus und Lucas, Leipzig, 1894, p. 97)[6] is that Josephus does not mean to imply that Abila was the only possession of Lysanias, and that he calls it the tetrarchy or kingdom of Lysanias because it was the last remnant of the domain of Lysanias which remained under direct Roman administration until the time of Agrippa.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 14.126 (14.7.4)

- ^ The Jewish War 1.248 (Whiston translation

- ^ Jewish Antiquities 14.330-331 (Whiston translation)

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 15.92.

- ^ The coins available on internet change frequently, though one should always be able to find examples on Wildwinds [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 182.

- ^ Josephus Jewish War Book 2, 12:8 and Antiquities xix.5, 1

- ^ P. Bockh, Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum 4521 and 4523.

- ^ John Hogg, "On the City of Abila, and the District Called Abilene near Mount Lebanon, and on a Latin Inscription at the River Lycus, in the North of Syria", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 20 (1850), p. 43; Raphaël Savignac, “Texte complet de l’inscription d’Abila relative a Lysanias,” Revue Biblique 9.4 (1912): 533-540 [for an English translation of this article, click here].

- ^ F.F.Bruce, New Testament Documents, chapter 7 Archived 2006-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gertrude Grether, "Livia and the Roman Imperial Cult", The American Journal of Philology, 67/3 (1946), p.231.

- ^ The Jewish War 2.215

- ^ Cited in Hogg, loc. cit., p.42

- WRIGHT, N.L. 2013: “Ituraean coinage in context.” Numismatic Chronicle 173: 55–71. (available online here)