Jewish women in early modern period

Jewish women in the early modern period played a role in all Jewish societies, though they were often limited in the amount that they were permitted to participate in the community at large. The largest Jewish populations during this time were in Italy, Poland-Lithuania, and the Ottoman Empire. Women's rights and roles in their communities varied across countries and social classes.

In general, girls did not receive an education unless they had means to hire a private tutor. Many were illiterate in their native language, and even fewer could read Hebrew. To the extent that women and girls could participate in worship, they were restricted to a particular section of the synagogue separate from the men.

The professions that women could serve in were restricted, as was the degree to which women were permitted to work. Across Jewish societies, women were encouraged to partake in charitable activities. Some women worked as midwives, gynecologists, or other female-focused professions.

Prominent women of this period included Ester Handali, Esperanza Melchi, and Dona Gracia Mendes.

Jewish Women in Italy

[edit]Source:[1]

Public life

[edit]Professions

[edit]Some Italian Jewish women became published writers. One notable author was Sarra Copia Sullam (1592–1641). She was accused of plagiarism by men that wanted to undermine her written accomplishments.[2] Jewish women also acted as ritual slaughterers. Ritual slaughter can be defined as killing animals for meat, typically in a religious ritual. Although women could act as ritual slaughterers, they had limited circumstances in which they were able to slaughter animals. Only qualified women were allowed to, and usually only in cases in which they needed to provide food for their families.[2] Women also served in the business sphere of Italian society. They acted as financial agents for their husbands, moneylenders, manufacturers of buttons and silk, cosmetic developers, etc. Their business was conducted both privately and publicly. This practice of women in business was disputed by men in society, as they thought women had no place in business.[3]

Worship

[edit]Jewish women were not allowed to worship communally in Jewish Italy. However, they did have a separate women's section in synagogue where they could worship and take part in their faith. Those women that could read Hebrew prayed daily. Translations from Hebrew to a more common language later appeared for those that did not know Hebrew—men also benefitted from these translations, as not all could men could read Hebrew. Women played a big role during worship by disrupting it. They would yell curses on their male counterparts and aired grievances they had. Because Jewish Italian women could not access the Torah during worship, they made the mappot, which was a binder with Torah scrolls. Some women even participated in daily fasting, prayer, and even abstaining from all pleasures.[4]

Private life

[edit]Education

[edit]Some Jewish girls were lucky enough to receive a complete Jewish education in Italy. However, many in society feared educated girls, but realized that illiterate women would not make for good homemakers or mothers. Because of this realization, daughters were taught how to write in Italian and some even learned Hebrew. This education was mainly taken care of at home, but some girls attended school. Occasionally women became teachers of Hebrew—they were called rabbit or rabbinate. These teachers would also get involved with healing, midwifery, and other domestic practices, not just Hebrew teaching.[5]

Marriage

[edit]Almost as soon as a young woman would reach puberty, she would become engaged. The usual age of marriage for Italian Jewish women was between fourteen and eighteen, while the typical age of marriage for males was twenty-four to twenty-eight. Marriage typically occurred after an engagement period called the shiddukhin which could last about a year or more. The engagement process was determined by parents; fathers typically made the matches between young men and women. These engagements were considered to be binding legal contracts. Financial considerations were extremely important in determining enagagements, as women brought a dowry to the marriage, and grooms supplied monetary sums if the marriage ended in divorce, he went to jail, or he died. As such, the sums were determined in the engagement contracts.

After the marriage occurred, young women left her family to join her husband's. She then became a homemaker and was expected to have children. Jewish women in Italy were unable to initiate divorce, so in order to divorce her husband, a woman would have to either involve her rabbi, violate marital laws, or try to convert either herself or her husband to Christianity, as the marriage would then become null.[6]

Jewish women in Poland-Lithuania

[edit]Public life

[edit]Professions

[edit]Even though Jewish women in Poland-Lithuania were mainly secluded in their homes, they did have access to becoming economically independent and were able to hold jobs of their own in society. They performed as bankers, money-lenders, arendas, inn or tavern managers, peddlers, store owners, and craft-makers, where they would sell at markets under tight restrictions. Families were often dependent on the financial contribution Jewish women made by working in these areas of trade.[7]

Women were not allowed to hold public office positions, due to male contempt for women. This did not mean, however, that they were unable to participate publicly. They could serve as court witnesses, petition signers, and bond guarantors.[7]

Charitable activities

[edit]In several communities in Poland-Lithuania, women were able to serve their communities and husbands as charity donation collectors. They participated in facilitating donations, monetary collecting, and giving money as well. As well as charity donations, older women in the community served as gynecologists for the town women. They would give exams, advice, and generally be consulted about many feminine problems women in town were experiencing. Women also acted charitably by advising other women about religious matters. These matters could include menstruation, adultery, and women's body preparation for burial.[8]

Private life

[edit]Women were excluded from almost all religious and intellectual parts of life in Poland-Lithuania.

Home

[edit]Jewish women in Poland-Lithuania tended to be secluded. They mainly stayed in their homes, and they were not allowed to have much contact with males (be they relatives or acquaintances) at all. Due to this seclusion, they had very limited access to traveling outside their home, and were told to go outside their homes only as "little as necessary".[7] Of course, this then meant that their professions were limited, as seen in the section above. Women were supposed to be second to their husbands in their own homes, and as subordinates, their husbands would be in control of all types of situations.[9] This led to the seclusion of women in their homes, applying to married and unmarried women.

Education

[edit]The education of Jewish girls was primarily done through privately hired tutors or a member of their family who had studied enough to pass on the knowledge. Girls would study religious readings instead of the more common Yiddish literature that were translated into Hebrew. Sometimes, girls studied in heder, which was why they were able to read Hebrew at all. However, most females in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth were illiterate, as female education was seen as much less important than male education.[7]

Worship

[edit]Women's worship was generally a private affair. They had synagogue access mainly on holidays and each Sabbath, however they had to sit separately from males during religious activity.[10] The synagogue was one of the acceptable public places for women to appear.[11] Worship for women consisted of prayer, including the Yiddish ttkines, or petitionary prayers. They're prayers depended on the time of year and even day, and could be modified for each individual reciting the prayers. This was due to each woman having own personal motivations and significance of religion, so the prayers needed to be unique to each and every one.[7] Some male rabbi even stated that women "were exempted from most of the commandments"[12] due to their status as women, so it is obvious that some were secluded from religious activity, however they had their own three "women's comandmants".[13]

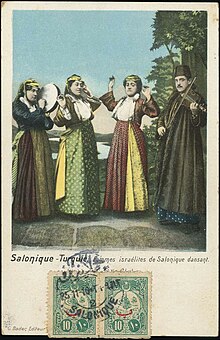

Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire

[edit]Education

[edit]The majority of the Jewish women in the Ottoman Empire came from Medieval Spain, where they predominantly spoke and used Ladino. Thus the language they used there traveled with them to the Middle East. Although men spoke Hebrew, many women could not, and were thus limited to Ladino.[14] Their illiteracy in the religious tongue restricted their religious practices and education, as most Jewish prayer and law books were written in Hebrew. Thus, women learned the laws of Judaism by modeling their mothers; their knowledge of Jewish law was limited to what they needed to know in order to run the domestic aspects of a Jewish household.[15] Although, men were responsible for teaching their wives and daughters Jewish law, specifically Hebrew prayers, they often lacked the motivation as most women were illiterate or learning took away time from children and household chores.[16] The only exception was daughters of rabbis, who would be surrounded by talmudic discourse at home and learn religious knowledge formally.[17]

During the Tanzimat Reforms, Jewish philanthropists began funding Jewish schools open to boys and girls. These schools' goal was to raise children in a modern, European fashion. Students were taught general subjects, along with Jewish History, Hebrew, and European languages. Formal education advanced girls' marriage prospects as they learned domestic skills, such as embroidery, along with hygiene and modern science.[18] Higher literacy rates among girls also changed their views on marriage; European books emphasized an ideal "love match" as opposed to a marriage of financial necessity.

Public life

[edit]Appearance

[edit]

Jewish women were conservatively dressed much like Muslims. When women went out in public, they covered themselves in a very large shawl that covered their whole body and wore a scarf on their heads.[19] All women wore the same type of clothing but the quality of their clothing implied whether or not they were wed. Married women had higher quality clothing.[20]

Professions

[edit]Women who worked in the Ottoman Empire were often not the breadwinners of their families but working out of necessity, due to being widowed or simply needing the extra money.[19] Peasant Jewish women tended to peddle at the marketplaces, selling chicken, eggs, wine, and other goods. Others worked in textile mills and craftwork.[21] These urban middle-class women were limited to jobs similar to peddling and farming. The poorest women worked as domestic help for wealthy Jews, in hopes of earning a dowry and marrying a man who could take care of them financially.[22]

Other, less common, professions Jewish women held were midwives and medical caregivers. Some women worked as healers. If a woman was ill (and common treatments were unsuccessful), a healer was hired to perform a ritual called indulco that involved the use of several substances including water, rosewater, honey, salt, and eggs. These women were popular in the Jewish community until they were banned by rabbis and public healthcare was established.[20]

Wealthier women living in the Ottoman Empire had greater options towards their occupations. These women acted as merchants, moneylenders, or real estate transactors, which allowed them to have some financial autonomy from their husbands, but also acquire personal liability.[23] Merchants sold silks, jewelry, and luxury goods to elites in the Ottoman Empire.[24] Money lenders and real estate transactors usually worked for their family business where these pursuits could be done from home. This was especially important in the Ottoman Empire as it was "undignified" for Sephardi women to be seen outside of their houses.[25] Jewish women also acted as intermediaries for Muslim women, as they faced even more restrictions regarding leaving their homes. Jewish women traded Muslim women's goods on their behalf in the market place and acted as brokers.[26] Jewish Women also had the privilege of being recognized as property owners.[24] This allowed them to lease their properties and earn their own living, independent of their husbands.[citation needed]

Women also participated in a lot of philanthropy for the community. Soup kitchens were stocked by more affluent women while breast milk was supplied to infants who were orphaned or in need by poorer women. They offered bread to people poorer than themselves as well as animals.[27]

Public places

[edit]Jewish women in the Ottoman Empire faced no legal restrictions to venture outside. However, most, especially those from wealthy families, chose to remain within their homes because of strict moral code.[28] Improper or inappropriate behavior could risk being the source of gossip and tarnish the family names. [28] However, lower-class women were forced to leave their homes to complete domestic work and sometimes business ventures. The public place is one where women would go to either do chores, such as using the oven for cooking, using the looms for spinning and weaving, or fetching water for laundry and cooking.[29] However, leaving the house was done in groups.[citation needed]

Especially in the Spanish Sephardic society, bath houses were attended regularly by Jewish women and were regarded as places of social gathering. In the Jewish community, the bath house is known as the mikveh. Women were obligated to go to the mikveh after their menses and after giving birth, to change their status of nidah. These women bathed with women of other religions at the mikveh such as Christians and Moslems. Occasionally, this practice was looked down upon by men, as they did not believe people of different religions should associate with each other.[30]

Worship

[edit]Jewish women were allowed to attend services in their synagogues. However, in the Spanish synagogues, women were separated from men during the services, a practice which was probably taken from Islam.[31] Though their presence at prayer services were permitted, most Jewish women could not read or understand Hebrew.[16] This placed a barrier on their participation and the fulfillment of this religious obligation as the service was typically conducted and recited in Hebrew.

Private life

[edit]

Marriage

[edit]It was common practice to be married off young as life expectancy was shorter than today.[20] Usually, daughters were married from oldest to youngest. They had to be well-rounded, respectable, virgin women whose family could offer a dowry.[20] The father of the bride took on the job of finding a good provider and was most concerned about finding a groom that was financially fit to care of his daughter. Usually, people married within their own social class, even if it was to their own relatives.[20] Moreover, elite women had to ability to refuse the spouses their parents chose for them and even initiate divorce.[32]

Jewish weddings in the Ottoman Empire had several components. Before the wedding, the bride went to a ritual bath, or Mikveh, to signify her purity in her upcoming nuptials. The women of her family attended the bath and assisted the bride. Throughout the ritual bath, songs were played to praise the bride.[20] Soon thereafter, the bride was led to the wedding and was taken by the man with a ring. She was not an active participant in the ceremony even though it's considered the most important thing in her life.[20]

After the couple was wedded, some sources say they moved in with the groom's family.[20] This sometimes led to tension and even divorce, as the women in the family would argue with each other.[20] Other sources indicate that the new couple moved in with the bride's family. This allowed the father to keep an eye on the groom and ensure that he was not taking advantage of or abusing his new wife.[32]

The Jewish doctrine of marriage was intended to protect women. The Ketubah allowed a woman to be financially secure and guaranteed that she could stay afloat in the case of divorce or widowhood.[33] It also defended women's rights against abusive husbands. Moreover, Jewish marriage contracts in the Ottoman Empire indicated that whatever a wife earns belongs to her. This assured a married woman's authority over her own assets.[34]

Household

[edit]Growing up, girls had to learn how to cook and take care of the home. If they did not, it would reflect badly upon their mothers who were supposed to teach them about domestic work. Women were judged by how they kept up the household. If they did everything that was expected of them with no complaints, did not ask for anything, and the home appeared clean and tidy, they would be known as a nikuchira, or a "good housewife who runs her home properly."[20] Women were expected to treat their husbands like royalty, or else he would find a new wife.[35] Many women were also restricted to their homes and many spent time in kortijo, or interior courtyards.[22] There, they would host guests and work on their chores and embroidering.

Pregnancy

[edit]In the middle of a woman's pregnancy, a cortar fashdura, or diaper-preparation ceremony occurred. Only women attended. The birth of a daughter would not be as welcomed as the birth of a boy because the family would now have to provide a dowry. The birth of a daughter also came with a fadamiento ceremony where the daughter would be named. The people that attended the daughter's ceremony would light candles to signify the daughters success in life. A new son would have a circumcision or Brit Milah ceremony.[20]

Status

[edit]The status of Jewish women was similar to other women in the Ottoman Empire. Generally speaking, a woman's status depended on the family she was born into and the family she married into.[32] Both of these factors largely focused on wealth in addition to whether or not the women was married.[citation needed] In both the Ottoman court and Beit Din, two women's witness testimony was equal to one man's.[36] Moreover, though women were highly dependent on men economically, Jewish women in the Ottoman Empire – like their Muslim counterparts – were recognized as legal property owners. Lastly, women also had marital privileges; elite women could initiate divorce and refuse spouses.[32] Additionally, they could also bring claims in Jewish and Ottoman court against their husbands.[citation needed] Their lives were centered around the home and domestic work, and they were usually always under the authority of men, but they nonetheless had rights.

Widows

[edit]A special status was given to Jewish widows in the Ottoman Empire. These women became heads of households if their husbands passed away. This new status was one of extreme independence, and it was regularly accepted in Ottoman society. Widows controlled their own dowry and inheritances; they also commonly joined the work force and were able to earn their own living.[34] This allowed them to be completely responsible for themselves and any children they had with their husband, giving widows immense power and freedom of movement in society.[37] In fact, many view widowhood as the greatest degree of freedom a woman could have in the Ottoman Empire.[38]

Notable Women

[edit]

Ester Handali was a Jewish Kira who provided services to the women in the Sultan's harem.[39] Handali not only supplied the women with personal goods,[40] but also acted as the intermediary between the secluded harem and the outside world.[41] She served Nurbanu Sultan and brought messages to foreign embassies. Though she began as a merchant to the harem, she was quickly promoted to a more diplomatic position.

Esperanza Melchi also served the Sultan's harem as a Kira and acted as an intermediary between the harem and foreign emissaries.[40] Originally she just brought Jewels and luxury goods to the Ottoman royalty. Eventually, she translated and wrote letters for Safiye, the Valide Sultan, to be delivered to Queen Elizabeth I.[40]

Doña Gracia Mendes was one of the wealthiest Jewish women in the Ottoman Empire and a great philanthropist. After being widowed, Mendes took over her husband's banking business and went into the international trade alongside her brother in-law.[22][41] She established a widespread financial and conmmercial network and worked with the Sultan to build business enterprises throughout the empire.[41][26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Adelman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. pp. 150–168. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ a b Adleman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Adelman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Adelman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. pp. 153–154. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Adelman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 156. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Adelman, Howard (1998). Italian Jewish Women. Wayne State University Press. pp. 156–159. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ a b c d e "Poland: Early Modern (1500–1795) | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-0878204595.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0878204595.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0878204595.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0878204595.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0878204595.

- ^ Fram, Edward (2007). My Dear Daughter. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0878204595.

woman's commandments

- ^ Schwarzwald, Ora (Rodrigue) (2017). "The Status of 16th Century Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire According to Seder Nashim and Shulḥan Hapanim in Ladino". Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal. 14 (1): 2. ISSN 1209-9392.

- ^ Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry: From the Golden Age of Spain to Modern Times. New York: New York University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0814797059.

- ^ a b Schwarzwald, Ora (2017). "The Status of 16th Century Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire According to Seder Nashim and Shulḥan Hapanim in Ladino". Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal. 12 (1): 3 – via Research Gate.

- ^ Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : from the Golden Age of Spain to modern times. New York: New York University Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : from the Golden Age of Spain to modern times. New York: New York University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ a b "Levant: Women in the Jewish Communities after the Ottoman Conquest of 1517". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hadar, Gila (2022). "Turkey: Ottoman and Post Ottoman". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Lamdan, Ruth (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 50. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 154993431.

- ^ a b c Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : From the Golden Age of Spain to Modern Times. New York: New York University Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ Lamdan, Ruth (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 55. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 154993431.

- ^ a b Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : from the Golden Age of Spain to modern times. New York: New York University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ Lamdan, Ruth (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 51. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 154993431.

- ^ a b Lamdan, Ruth (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 57. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 154993431.

- ^ "Turkey: Ottoman and Post Ottoman". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ a b Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : from the Golden Age of Spain to modern times. New York: New York University Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ Levine Melammed, Renee (1991). "Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods". In Baskin, Judith (ed.). Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. pp. 119–121. ISBN 0-8143-2091-0. OCLC 246799502.

- ^ Levine Melammed, Renee (1191). "Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Period". In Baskin, Judith (ed.). Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-8143-2713-3. OCLC 39307316.

- ^ Levine Melammed, Renee (1991). "Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods". In Baskin, Judith (ed.). Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Detroit, Milchigen: Wayne State University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ a b c d Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry : from the Golden Age of Spain to modern times. New York: New York University Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.

- ^ "Art of the Ketubah: Decorated Jewish Marriage Contracts". Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ a b Lamdan, Ruth (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 52. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. S2CID 154993431.

- ^ Lamdan, Ruth (2000). A Separate People : Jewish Women in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt in the Sixteenth Century. Boston: Brill. p. 98. ISBN 90-04-11747-4. OCLC 43903771.

- ^ Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry: From the Golden Age of Spain to Modern Times. New York: New York University Press. p. 219. ISBN 0814797059.

- ^ Melammed, Renee (1998). Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods. Wayne State University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Melammed, Renee L. (1998). "Sephardi Women in the Medieval and early Modern Periods". In Judith, Baskin (ed.). Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0814327133.

- ^ Levine Melammed, Renee (1991). "Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods". In Baskin, Judith (ed.). Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Judith Reesa Baskin. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-8143-2713-3. OCLC 39307316.

- ^ a b c Lamdan (2007). "Jewish Women as Providers in the Generations Following the Expulsion from Spain". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (13): 58–59. doi:10.2979/nas.2007.-.13.49. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 154993431 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Sezgin, Pamela (2005). "Jewish Women in the Ottoman Empire". In Zohar, Zion (ed.). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry: From the Golden Age of Spain to Modern Times. New York: New York University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9. OCLC 57514982.