Industrial unionism

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations. De Leon believed that militarized Industrial unions would be the vehicle of class struggle.

Industrial unionism contrasts with craft unionism, which organizes workers along lines of their specific trades.[1]

History in the United States

[edit]Early history

[edit]In 1893, the American Railway Union (ARU) was formed in the United States, by Eugene Debs and other railway union leaders, as an industrial union in response to the perceived limitations of craft unions. Debs himself gave an example of the inadequacies that his fellows at the time felt towards organising by craft. He recounts, that in 1888, a strike was called by train drivers and railway firemen on the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railways, but other employees, particularly conductors, who were organised into a different unions did not join that strike, with strikebreakers brought on to help their employers.[2]

In June 1894, the ARU voted to join in solidarity with the ongoing Pullman Strike, and within hours of the union lending support to the boycott, traffic from the Pullman Company traffic ceased to move from Chicago to the Western United States. The sympathy strike then spread to the Southern and later the Eastern United States. A statement was issued by the chairman of the General Managers Association, which represented railway companies that were mainly situated around Chicago, admitted:

We can handle the railway brotherhoods, but we cannot handle the A.R.U.... We cannot handle Debs. We have got to wipe him out.[3]

The General Managers Association turned to the United States government, which immediately sent the United States Army and the United States Marshals to force an end to the strike.

Popularisation and radicalism

[edit]

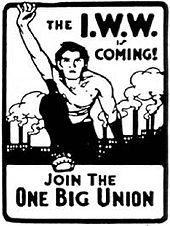

In 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was formed in Chicago at the First Annual Convention of the IWW, six weeks after the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League. It was created as a rejection of the craft unionism philosophy that the American Federation of Labor endorsed, and from its inception, the IWW would organize without regard to sex, skills, race, creed, or national origin unlike the Federation.[4][5] It argued for a mass-oriented labour movement, the One Big Union, and declared that "the working class and the employing class have nothing in common."[6][7]

The critiques of the Federation included the strikebreaking that member unions participated in against each other, jurisdictional squabbling, autocratic leadership,[8] and a strong relationship between union and business leaders in the National Civic Federation.[9]

After Debs' six month imprisonment after the ARU's dissolution, he, along with Ed Boyce, Bill Haywood and others, were instrumental in launching the Western Labor Union, soon renamed the American Labor Union, which was the precursor to the IWW. The new organisation was militant in its operations and housed revolutionary socialist and radical ideals, with Boyce proclaiming that labour must "abolish the wage system which is more destructive of human rights and liberty than any other slave system devised."[10] The preamble of the IWW's constitution further emphasised that "There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on...."[11]

Persecution

[edit]In the United States, IWW executive board officer Frank Little was lynched from a railway trestle.[12] Seventeen Wobblies in Tulsa were beaten by a mob and driven out of town.[12] In the third quarter of 1917, the New York Times ran sixty articles attacking the IWW.[12] The Justice Department launched raids on IWW headquarters across the country.[12] The New-York Tribune suggested that the IWW was a German front, responsible for acts of sabotage throughout the nation.[12]

Writing in 1919, Paul Brissenden quoted an IWW publication in Sydney, Australia:

All the machinery of the capitalist state has been turned against us. Our hall has been raided periodically as a matter of principle, our literature, our papers, pictures, and press have all been confiscated; our members and speakers have been arrested and charged with almost every crime on the calendar; the authorities are making unscrupulous, bitter and frantic attempts to stifle the propaganda of the I.W.W.[13]

Brissenden also recorded that:

...several laws have been enacted which have been more or less directly aimed at the Industrial Workers of the World. Australia led off with the "Unlawful Associations Act" passed by the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth in December, 1916... Within three months of the passage of the Australian Act, the American States of Minnesota and Idaho passed laws "defining criminal syndicalism and prohibiting the advocacy thereof." In February, 1918, the Montana legislature met in extraordinary session and enacted a similar statute.[14]

While Brissenden notes that IWW coal miners in Australia successfully used direct action to free imprisoned strike leaders and to win other demands, Wobbly opposition to conscription during World War I "became so obnoxious" to the Australian government that laws were passed which "practically made it a criminal offense to be a member of the I.W.W."[15]

One Big Union

[edit]

Historically, industrial unionism has frequently been associated with the concept of One Big Union. On July 12, 1919, The New England Worker published "The Principle of Industrial Union":

The principle on which industrial unionism takes its stand is the recognition of the never ending struggle between the employers of labor and the working class. [The industrial union] must educate its members to a complete understanding of the principles and causes underlying every struggle between the two opposing classes. This self-imposed drill, discipline and training will be the methods of the O. B. U.[16]

In short the Industrial Union, is bent upon forming one grand united working class organization and doing away with all the divisions that weaken the solidarity of the workers to better their conditions.[16]

Revolutionary Industrial Unionism, that is the proposition that all wage workers come together in organization according to industry; the groupings of the workers in each of the big divisions of industry as a whole into local, national, and international industrial unions; all to be interlocked, dovetailed, welded into One Big Union for all wage workers; a big union bent on aggressively forging ahead and compelling shorter hours, more wages and better conditions in and out of the work shop... until the working class is able to take possession and control of the machinery, premises, and materials of production right from the capitalists' hands...[16]

Industrial unionism by country

[edit]Australia

[edit]Verity Burgmann asserts in Revolutionary industrial unionism that the IWW in Australia provided an alternate form of labour organising, to be contrasted with the Labourism of the Australian Labor Party and the Bolshevik Communism of the Communist Party of Australia. Revolutionary industrial unionism, for Burgmann, was much like revolutionary syndicalism, but focused much more strongly on the industrial nature of unionism. Burgmann saw Australian syndicalism, particularly anarcho-syndicalism, as focused on mythic small shop organisation. For Burgmann, the IWW's vision was always a totalising vision of a revolutionary society: the Industrial Commonwealth.[17]

Korea

[edit]The theory and practice of industrial unionism is not confined to the western or the English-speaking world. The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) is committed to reorganizing their current union structure along the lines of industrial unionism.[18]

South Africa

[edit]The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) is also organized along the lines of industrial unionism.[19]

United Kingdom

[edit]Marion Dutton Savage associates the spirit of industrial unionism with "the aspiration of workers for the control of industry" inspired by Robert Owen in 1833-34. The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (GCTU) recruited skilled and unskilled workers from many industries, with membership growing to half a million within a few weeks. Frantic opposition forced the GCTU to collapse after a few months, but the ideals of the movement lingered for a time. After Chartism failed, British unions began to organize only skilled workers, and began to limit their goals in tacit support of the existing organization of industry.[20]

A new union movement that was "distinctly class conscious and vaguely Socialistic" began to organize unskilled workers in 1889.[21]

Industrial unionism thence proceeded primarily by combining craft unions into industrial formations, rather than through the birth of new industrial organizations. Industrial organizations prior to 1922 included the National Transport Workers' Federation, the National Union of Railwaymen, and the Miners' Federation of Great Britain.[22]

In 1910 Tom Mann went to France and became acquainted with syndicalism. He returned to Britain and helped to organize the Workers' International Industrial Union, which was similar to the IWW from North America.[23]

United States

[edit]In 1904, the Western Federation of Miners was under significant pressure from military and employer violence in the Colorado Labor Wars. Its labour federation the American Labor Union had not gained significant membership. The AFL was the largest organized labour federation, and the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE) felt isolated. When they applied to the AFL for a charter, the Scranton Declaration of 1901 was the AFL's guiding principle.[24]

Gompers had promised that each trade and craft would have its own union. The Scranton Declaration acknowledged that one affiliate, the United Mine Workers was formed as an industrial union but that other skilled trades—carpenters, machinists, etc. were organized as powerful craft unions. These craft unions refused to allow any encroachment upon their "turf" by the industrial unionists. The concept came to be known as voluntarism.

The federation turned the UBRE down in accord with the voluntarism principle. The Scranton Declaration acknowledging voluntarism was adhered to, even though the craft-based railway brotherhoods had not yet joined the AFL.[25] The AFL was holding the door open for craft unions that might join, and slamming it in the face of the industrial unions who wanted to join. The following year, the 2000-member UBRE joined the organizing convention of the IWW.

Before Herbert Hoover became president, he befriended AFL President Gompers. Hoover, as the former United States Food Administrator, president of the Federated Engineering Societies, and then Secretary of Commerce in the Harding Cabinet in 1921, invited the heads of several "forward-looking" major corporations to meet with him.

[Hoover] asked these men why their companies didn't sit down with Gompers and try to work out an amicable relationship with organized labor. Such a relationship, in Hoover's opinion, would be a bulwark against the spread of radicalism reflected in the rise of the "Wobblies," the Industrial Workers of the World. The Hoover initiative got no encouragement from those at the meeting. The obstacles that Hoover did not comprehend, [Cyrus] Ching recorded in his memoir, were that Gompers had no standing in the affairs of any company except to the extent that AFL unions had organized the workers, and that the federation's focus on craft unionism precluded any effective organization of the mass-production industries by [the AFL's] affiliates.[26]

The craft-based AFL had been slow to organize industrial workers, and the federation remained steadfastly committed to craft unionism. This changed in the mid-1930s when, after passage of the National Labor Relations Act, workers began to clamor for union membership. In competition with the CIO movement, the AFL established Federal Labor Unions (FLUs), which were local industrial unions affiliated directly with the AFL,[27] a concept initially envisioned in the 1886 AFL Constitution. FLUs were conceived as temporary unions, many of which were organized on an industrial basis. In keeping with the craft concept, FLUs were designed primarily for organizing purposes, with the membership destined to be distributed among the AFL's craft unions after the majority of workers in an industry were organized.

In the United States, the conception of industrial unionism in the 1920s certainly differed from that of the 1930s, for example. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) primarily practiced a form of industrial unionism prior to its 1955 merger with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which was mostly craft unions. Unions in the resulting federation, the AFL–CIO, sometimes have a mixture of tendencies.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Savage 1922, p. 3.

- ^ Brissenden 1919, p. 86.

- ^ Rayback 1966, p. 201.

- ^ Solidarity Forever—An oral history of the IWW, Stewart Bird, Dan Georgakas, Deborah Shaffer, 1985, page 140.

- ^ Cahn 1972, p. 201.

- ^ Fusfeld 1985, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Constitution and By-Laws of the Industrial Workers of the World, Preamble, 1905, https://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/constitution/1905const.html Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ Brissenden 1919, p. 87.

- ^ Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Dubofsky 2000, p. 40.

- ^ Preamble to the Constitution, Industrial Workers of the World, 1905, https://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/constitution/1905const.html retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b c d e Starr 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Brissenden 1919, p. 340, quoting a March 17, 1917 Solidarity reprint of Direct Action (Sydney).

- ^ Brissenden 1919, p. 280.

- ^ Brissenden 1919, pp. 341–342.

- ^ a b c Daniel Bloomfield, Selected Articles on Modern Industrial Movements, H.W. Wilson Co., 1919, pages 39–40.

- ^ Burgmann 1995.

- ^ This is KCTU, Building Industrial Unionism https://kctu.org/2003/html/sub_01.php Archived 2005-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ About Cosatu, One industry, one union - one country, one federation "About Cosatu". Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ Savage 1922, p. 6.

- ^ Savage 1922, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Savage 1922, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Savage 1922, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Thompson & Murfin 1976, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Raskin 1989.

- ^ Cahn 1972, pp. 253–254.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bohn, William E. (1912). "The Industrial Workers of the World". The Survey: Social, Charitable, Civic: A Journal of Constructive Philanthropy. 28. New York: The Charity Organization Society: 220–225. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- Brissenden, Paul Frederick (1919). The I.W.W.: A Study of American Syndicalism. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Burgmann, Verity (1995). Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47123-7.

- Cahn, William (1972). A Pictorial History of American Labor: The Contributions of the Working Man and Woman to America's Growth, from Colonial Times to Present. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-50040-8.

- Cannon, James P. (1955). "The I.W.W." (PDF). Fourth International. 16 (3). New York: Fourth International Publishing Association: 75–86. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Carlson, Peter (1983). Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01621-5.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn (1987). 'Big Bill' Haywood. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312012724.

- — (2000). McCartin, Joseph A. (ed.). We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. The Working Class in American History (abridged ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06905-5.

- Friedman, Morris (1907). The Pinkerton Labor Spy. New York: Wilshire Book Co. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Fusfeld, Daniel R. (1985). The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company.

- Grob, Gerald N. (1961). Workers and Utopia: A Study of Ideological Conflict in the American Labor Movement, 1865–1900. Northwestern University Studies in History. Vol. 2. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

- Raskin, A. H. (1989). "Cyrus S. Ching: Pioneer in Industrial Peacemaking" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. 112 (8). Washington: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: 22–35. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Rayback, Joseph G. (1966). A History of American Labor. New York: Free Press.

- Savage, Marion Dutton (1922). Industrial Unionism in America. New York: The Ronald Press Company. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Starr, Kevin (1997) [1996]. Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511802-5.

- Thompson, Fred W.; Murfin, Patrick (1976). The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years, 1905–1975. Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World.

- Tuck, J. Hugh (1983). "The United Brotherhood of Railway Employees in Western Canada, 1898–1905". Labour / Le Travail. 11: 63–88. doi:10.2307/25140201. JSTOR 25140201.