Energy in Ireland

Ireland is a net energy importer. Ireland's import dependency decreased to 85% in 2014 (from 89% in 2013). The cost of all energy imports to Ireland was approximately €5.7 billion, down from €6.5 billion (revised) in 2013 due mainly to falling oil and, to a lesser extent, gas import prices.[1] Consumption of all fuels fell in 2014 with the exception of peat, renewables and non-renewable wastes.[1]

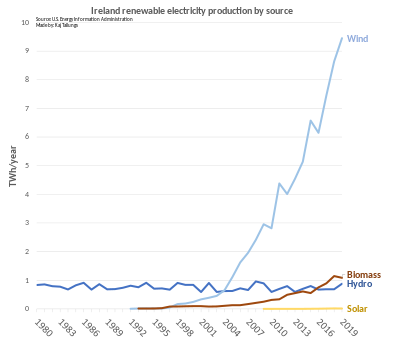

Final consumption of electricity in 2017 was 26 TWh, a 1.1% increase on the previous year. Renewable electricity generation, consisting of wind, hydro, landfill gas, biomass and biogas, accounted for 30.1% of gross electricity consumption.[2] In 2019, it was 31 TWh with renewables accounting for 37.6% of consumption.[3]

Energy-related CO2 emissions decreased by 2.1% in 2017 to a level 17% above 1990 levels. Energy-related CO2 emissions were 18% below 2005 levels.[2] 60% of Irish greenhouse gas emissions are caused by energy consumption.[4]

Statistics

[edit]

|

|

|

CO2 emissions: |

Energy plan

[edit]Ireland had a plan to reduce by 30% its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to 2005. This was improved, with a new target aiming for Ireland to achieve a 7% annual average reduction in greenhouse gas emissions between 2021 and 2030.[6]

Primary energy sources

[edit]Fossil fuels

[edit]Natural gas

[edit]There have been four commercial natural gas discoveries since exploration began offshore Ireland in the early 1970s; namely the Kinsale Head, Ballycotton and Seven Heads producing gas fields off the coast of Cork and the Corrib gas field off the coast of Mayo.[7]

The main natural gas/Fossil gas fields in Ireland are the Corrib gas project and Kinsale Head gas field. Since the Corrib gas field came on stream in 2016, Ireland reduced its energy import dependency from 88% in 2015 to 69% in 2016.[8]

The Corrib Gas Field was discovered off the west coast of Ireland in 1996. Approximately 70% of the size of the Kinsale Head field, it has an estimated producing life of just over 15 years.[citation needed] Production began in 2015.[9] The project was operated by Royal Dutch Shell until 2018, and from 2018 onwards by Vermilion Energy.[10]

The indigenous production of gas from 1990 to 2019 is shown on the graph. Figures are in thousand tonnes of oil equivalent.[11]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Since 1991 Ireland has imported natural gas by pipeline from the British National Transmission System in Scotland. This was from the Interconnector IC1 commissioned in 1991 and Interconnector IC2 commissioned in 2003.

The import of gas from 1990 to 2019 is shown on the graph. Figures are in thousand tonnes of oil equivalent.[11]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Peat

[edit]Ireland uses peat, a fuel composed of decayed plants and other organic matter which is usually found in swampy lowlands known as bogs, as energy which is not common in Europe. Peat in Ireland is used for two main purposes – to generate electricity and as a fuel for domestic heating. The raised bogs in Ireland are located mainly in the midlands.

Bord na Móna is a commercial semi-state company that was established under the Turf Development Act 1946. The company was responsible for the mechanised harvesting of peat in Ireland.[12] The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), under the remit of the Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage, deals with Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas under the Habitats Directive. Restrictions have been imposed on the harvesting of peat in certain areas under relevant designations.[12]

The West Offaly Power Station was refused permission to continue burning peat for electricity and closed in December 2020.[13]

Peat fired power stations will cease by 2023. Edenderry is the last peat fuelled power plant left operating in Ireland. Bord na Móna has been co-firing peat with biomass at Edenderry for more than 5 years.[12] From 2023 it will become solely Biomass.[14]

Coal

[edit]Coal remains an important solid fuel that is still used in home heating by a certain portion of households. In order to improve air quality, certain areas are banned from burning so-called 'smoky coal.' The regulations and policy relating to smoky fuel are dealt with by the Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications.[15]

Ireland has a single coal-fired power plant at Moneypoint, Co. Clare which is operated by ESB Power Generation. At 915MW output, it is Ireland's largest power station. The station was originally built in the 1980s as part of a fuel diversity strategy and was significantly refurbished during the 2000s to make it fit for purpose in terms of environmental regulations and standards. Moneypoint is considered to have a useful life until at least 2025[15] but ESB Power Generation has indicated that it intends to close Moneypoint and convert it to a green energy hub.[16]

Coal fired power stations will cease by 2025.[6]

Oil

[edit]There have been no commercial discoveries of oil in Ireland to date.[7]

One Irish oil explorer is Providence Resources, with CEO Tony O'Reilly, Junior and among the main owners Tony O'Reilly with a 40% stake.[17]

The oil industry in Ireland is based on the import, production and distribution of refined petroleum products. Oil and petroleum products are imported via oil terminals around the coast. Some crude oil is imported for processing at Ireland's only oil refinery at Whitegate Cork.[18]

Renewable Energy

[edit]| Achievement | Year | Achievement | Year | Achievement | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 2009 | 10% | 2017 | 15% | not achieved yet[5] |

Renewable energy includes wind, solar, biomass and geothermal energy sources.

Under the original 2009 Renewable Energy Directive Ireland had set a target of producing 16% of all its energy needs from renewable energy sources by 2020 but that has been updated by a second Renewable Energy Directive whose targets are 32% by 2030. Between 2005 and 2014 the percentage of energy from renewable energy sources grew from just 3.1% to 8.6% of total final consumption. By 2020 the overall renewable energy share was 13.5%, short of its Renewable Energy Drive target of 16%.[19] Renewable electricity accounted for 69% of all renewable energy used in 2020, up from two thirds (66.8%) in 2019.[19]

The country has a large and growing installed wind power capacity at 4,405 MW by the end of 2021 producing 31% of all its electricity needs in that year.[20] By February 2024, there was 1GW of solar PV capacity connected to the grid.[21] By April 2024, the grid had 1GW of storage capacity with almost 750MW of that capacity in the form of battery storage[22] the rest supplied by Turlough Hill.Biomass power

[edit]Non-renewable energy refers to energy generated from domestic and commercial waste in Energy-from-Waste plants. The Dublin Waste-to-Energy Facility burns waste to provide heat to generate electricity and provide district heating for areas of Dublin.

The contribution of non-renewable energy to Ireland’s energy supply is show by the graph. The quantity of energy is in thousand tonnes of oil equivalent.[11]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Solar power

[edit]Photovoltaic (PV) modules on domestic roofs are becoming more common, following the removal of VAT and an increase in grants, with 60,000 homes fitted by summer 2023, increasing at 500 per week, with a 2023 capacity of 700MW that is generating 600,000Mwh. A University College Cork satellite survey identified 1 million homes with a suitable orientation to suit 10 roof panels. [23]

Wind power

[edit]

Wood

[edit]The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine have responsibility for the Forest Service and forestry policy in Ireland. Coillte (a commercial state company operating in forestry, land based businesses, renewable energy and panel products) and Coford (the Council for Forest Research and Development) also fall under that Department's remit.

Wood is used by households that rely on solid fuels for home heating. It is used in open fireplaces, stoves and biomass boilers.

In 2014, the Department produced a draft bioenergy strategy. In compiling the strategy, the Department worked closely with the Department of Agriculture in terms of the potential of sustainable wood biomass for energy purposes.[27]

Electricity

[edit]Final consumption of electricity in 2014 was 24 TWh. Electricity demand which peaked in 2008 has since returned to 2004 levels. Renewable electricity generation, consisting of wind, hydro, landfill gas, biomass and biogas, accounted for 22.7% of gross electricity consumption.[1]

The use of renewables in electricity generation in 2014 reduced CO2 emissions by 2.6 Mt. In 2014, wind generation accounted for 18.2% of electricity generated and as such was the second largest source of electricity generation after natural gas.[1]

The carbon intensity of electricity fell by 49% since 1990 to a new low of 457 g CO2/kWh in 2014.[1]

Ireland is connected to the adjacent UK National Grid at an electricity interconnection level of 9% (transmission capacity relative to production capacity).[28] In 2016, Ireland and France agreed to advance the planning of the Celtic Interconnector, which if realized will provide the two countries with a 700 MW transmission capacity by 2025.[29]

Energy storage

[edit]The utility ESB operates a pumped storage station in Co. Wicklow called Turlough Hill with 292 MW peak power capacity.[30] A Compressed air energy storage project in salt caverns near Larne received €15m of funding from EU. It won a further €90m from the EU in 2017 as a project of common interest (PCI).[31] It was intended to provide a 250-330 MW buffer for 6–8 hours in the electricity system.[32] This project has since been cancelled due to the company in charge of the project, Gaelectric, entering administration in 2017.[31]

Statkraft completed a 11MW, 5.6MWh lithium-ion battery energy storage system in April 2020.[33] ESB has developed a battery facility on the site of its Aghada gas-fired power station in Co. Cork.

Several other battery energy storage systems are in development. ESB and partner company Fluence are developing a further 60 MWh of battery capacity at Inchicore in Dublin, a 150 MWh / 75 MW plant in Poolbeg, Dublin,[34] and a 38 MWh plant at Aghada. These facilities are primarily aimed at providing ancillary grid services.[35]

The depleted Kinsale gas field was used as a natural gas storage facility until its closure in 2017.[36] Since then, there has been no dedicated large-scale natural gas storage capacity in the country. A government-commissioned report on security of energy supply recommended the development of a strategic gas storage facility or the use of a Floating Storage and Regasification Unit.[37]

Imported crude oil and petroleum products are stored at oil terminals around the coast.[38] A strategic reserve of petroleum products, equivalent to 90 days usage, is stored at some of these terminals. The National Oil Reserves Agency is responsible for the strategic reserve.[39] The largest energy store in Ireland is the coal reserve for Moneypoint power station.[16]

Carbon Tax

[edit]In 2010 the country's carbon tax was introduced[40] at €15 per tonne of CO2 emissions[41] (approx. US$20 per tonne).[42]

The tax applies to kerosene, marked gas oil, liquid petroleum gas, fuel oil, and natural gas. The tax does not apply to electricity because the cost of electricity is already included in pricing under the Single Electricity Market (SEM). Similarly, natural gas users are exempt if they can prove they are using the gas to "generate electricity, for chemical reduction, or for electrolytic or metallurgical processes".[43] Partial relief is granted for natural gas covered by a greenhouse gas emissions permit issued by the Environmental Protection Agency. Such gas will be taxed at the minimum rate specified in the EU Energy Tax Directive, which is €0.54 per megawatt-hour at gross calorific value."[44] Pure biofuels are also exempt.[45] The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) estimated costs between €2 and €3 a week per household:[46] a survey from the Central Statistics Office reports that Ireland's average disposable income was almost €48,000 in 2007.[47]

Activist group Active Retirement Ireland proposed a pensioner's allowance of €4 per week for the 30 weeks currently covered by the fuel allowance and that home heating oil be covered under the Household Benefit Package.[48]

The tax is paid by companies. Payment for the first accounting period was due in July 2010. Fraudulent violation is punishable by jail or a fine.[49]

The NGO Irish Rural Link[50] noted that according to ESRI a carbon tax would weigh more heavily on rural households.[51] They claim that other countries have shown that carbon taxation succeeds only if it is part of a comprehensive package that includes reducing other taxes.[52]

In 2011, the coalition government of Fine Gael and Labour raised the tax to €20/tonne. Farmers were granted tax relief.[53]

The Minister for Finance introduced, with effect from 1 May 2013, a solid fuel carbon tax (SFCT). The Revenue Commissioners have responsibility for administering the tax. It applies to coal and peat and is chargeable per tonne of product.[12]

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI)

[edit]The Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) was established as Ireland's national energy authority under the Sustainable Energy Act 2002. SEAI's mission is to play a leading role in transforming Ireland into a society based on sustainable energy structures, technologies and practices. To fulfil this mission SEAI aims to advise the Government, and deliver a range of programmes aimed at a wide range of stakeholders.[54]

Nuclear energy

[edit]The Single Electricity Market encompassing the entire island of Ireland does not, and has never, produced any electricity from nuclear power stations. The production of electricity for the Irish national grid (Eirgrid), by nuclear fission, is prohibited in the Republic of Ireland by the Electricity Regulation Act, 1999 (Section 18).[55] The enforcement of this law is only possible within the borders of Ireland, and it does not prohibit consumption. Since 2001 in Northern Ireland and 2012 in the Republic, the grid has become increasingly interconnected with the neighbouring electric grid of Britain, and therefore Ireland is now partly powered by overseas nuclear fission stations.[56][57]

A ‘Eurobarometer’ survey in 2007 indicated that 27 percent of the citizens of Ireland were in favour of an “increased use” of nuclear energy.[58]

As of 2014, a Generation IV nuclear station was envisaged in competition with a biomass burning facility to succeed Ireland's single largest source of greenhouse gases, the coal burning Moneypoint power station, when it retires, c. 2025.[59][60]

In 2015 a National Energy Forum was founded to decide upon generation mixes to be deployed in the Republic of Ireland,[61] out to 2030. This forum has yet to be convened (Oct 2016).See also

[edit]- Electricity sector in Ireland

- Renewable energy in the Republic of Ireland

- List of power stations in the Republic of Ireland

- Oil terminals in Ireland

- Whitegate refinery

- Renewable energy by country

- United Kingdom–Ireland natural gas interconnectors

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Energy in Ireland 1990-2014" (PDF). Energy in Ireland 1990-2014. SEAI. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Energy In Ireland 2018" (PDF). SEAI. 2018.

- ^ "Energy In Ireland 2020" (PDF). SEAI. 2020.

- ^ "CO2 emissions". SEAI. 2019.

- ^ a b "Energy consumption in Ireland". 2020.

- ^ a b "National Energy & Climate Plan 2021-2030" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Oil and Gas (Exploration & Production)". Oil and Gas (Exploration & Production). Department of Communications, Energy & Natural Resources. 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Energy in Ireland 1990-2016. 2017 Report" (PDF). Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland. December 2017. p. 4. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Murtagh, Peter (30 December 2015). "Natural gas begins flowing from controversial Corrib field". The Irish Times. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Falconer, Kirk (3 December 2018). "Shell Completes $1.3 bln sale of Corrib gas field stake to CPPIB". PE Hub. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland". www.seai.ie/data-and-insights. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Peat". Department of Communications, Climate Action & Environment. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Kathleen O'Sullivan "West Offaly Power Station closure: ‘A final plea to ensure reason and sense prevails’" AgriLand, Dec 11, 2020.

- ^ "Former peat power station needs 1m tonnes of biomass". 11 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Coal". Department of Communications, Climate Action & Environment. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Moneypoint Power Station". ESB Corporate. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Irish oil find expected to yield 280m barrels of oil, Ireland's first offshore oilfield will yield much more oil than expected, Providence Resources said The Guardian 10 October 2012

- ^ "Energy Use Overview". www.seai.ie. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Renewables". Sustainable Energy Authority Of Ireland. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Wind energy in Europe: 2021 Statistics and the outlook for 2022-2026". WindEurope. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "One Giga Watt of solar capacity now connected to electricity grid". RTE. 17 February 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Ottilie Von Henning (25 April 2024). "ESB reaches 1GW of energy storage on Irish network". CURRENT+-. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "Ireland's solar revolution: the country's fastest-growing renewable power source is having a profound impact". 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Wind Statistics". iwea.com. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Wind Energy Powers Ireland to Renewable Energy Target". 28 January 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Chloé. "New record set for wind power generation in 2023". windenergyireland.com. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "Solid Fuels | Solid Fuel Heating Ireland". Wood. Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources. 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ COM/2015/082 final: "Achieving the 10% electricity interconnection target" Text PDF page 2-5. European Commission, 25 February 2015. Archive Mirror

- ^ "President Hollande and An Taoiseach Kenny agree €1 billion Ireland-France Electricity Interconnector". 4coffshore.com. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Turlough Hill". ESB Archives. 1 March 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Larne CAES plans withdrawn - Modern Power Systems". www.modernpowersystems.com. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Gaelectric to get €8.3m EU funds for energy storage project". The Irish Times. 1 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Grid Services and Batteries". www.statkraft.com. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "ESB officially launches major battery project at Poolbeg Energy Hub as part of €300m investment". ESB. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "ESB and Renewable Energy". ESB Corporate. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Stokes, Bob. "GAS STORAGE". Kinsale Energy. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Review of the Security of Energy Supply of Ireland's Electricity and Natural Gas Systems" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications. 28 April 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Fuel Oil News Wallchart 2021

- ^ "NORA". www.nora.ie. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ The 2010 budget was delivered in December 2009

- ^ "Carbon tax of €15 a tonne announced". Inside Ireland. 9 December 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ €1 was equal to US$1.32 as of August 2010. See: 9 August 2010, Currency Calculator Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bord Gáis Energy (2010). "Help & Questions – Home Gas – Carbon Tax". Bord Gáis Energy website. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ Revenue. "Guide to Natural Gas Carbon Tax". Revenue: Irish tax and customs. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ McGee, Harry (30 January 2010). "Producers of biofuels want changes to carbon tax". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ McGee, Harry (12 December 2009). "Carbon tax to drive up fuel costs". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Carr, Aoife (2009). "Irish household income up 10% in 2007". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ "Multy woman among group arguing for aid for elderly". Westmeath Examiner. 28 July 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Revenue (2010). "Guide to Natural Gas Carbon Tax" (PDF). Revenue: Irish tax and customs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Irish Rural Link – Naisc Tuaithe na hÉireann". irishrurallink.ie. Archived from the original on 7 April 2003. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ "A Carbon Tax for Ireland" (PDF). ESRI Working Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Carbon Tax and Rural Ireland" (PDF). Irish Rural Link Carbon Tax Briefing Note. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2011.

- ^ "Budget 2012: The main points ... from mortgage relief to carbon tax". The Irish Independent. 6 December 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "About Us". Sustainable Energy Authority Of Ireland. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Electricity Regulation Act, 1999 (Section 18)". www.irishstatutebook.ie.

- ^ "That nukes that argument". 7 June 2013.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140721003556/https://www.dcenr.gov.ie/NR/rdonlyres/DD9FFC79-E1A0-41AB-BB6D-27FAEEB4D643/0/DCENRGreenPaperonEnergyPolicyinIreland.pdf page 50

- ^ "Ireland Rejects Uranium Prospecting Applications". www.nucnet.org.

- ^ "Emerging Nuclear Energy Countries". World Nuclear Association. April 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140721003556/https://www.dcenr.gov.ie/NR/rdonlyres/DD9FFC79-E1A0-41AB-BB6D-27FAEEB4D643/0/DCENRGreenPaperonEnergyPolicyinIreland.pdf page 50 to 60

- ^ "Ireland's Transition to a Low Carbon Energy Future 2015-2030" (PDF). Retrieved 30 July 2016.