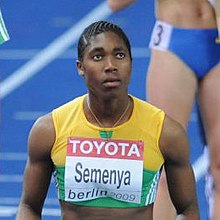

Caster Semenya

Caster Semenya in 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | South African | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 7 January 1991 Pietersburg, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | North-West University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 70 kg (154 lb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Running | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Event(s) | 800 metres, 1500 metres | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Now coaching | Glenrose Xaba | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal bests | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mokgadi Caster Semenya OIB (born 7 January 1991) is a South African middle-distance runner and winner of two Olympic gold medals[4] and three World Championships in the women's 800 metres. She first won gold at the World Championships in 2009 and went on to win at the 2016 Olympics and the 2017 World Championships, where she also won a bronze medal in the 1500 metres. After the doping disqualification of Mariya Savinova, she was also awarded gold medals for the 2011 World Championships and the 2012 Olympics.[5][6][7]

Following Semenya's victory at the 2009 World Championships, she was made to undergo sex testing, and cleared to return to competition the following year.[8][9] The decision to perform sex testing sparked controversy in the sporting world and in Semenya's home country of South Africa. Later reports disclosed that Semenya has the intersex condition 5α-Reductase 2 deficiency and natural testosterone levels in the typical male range.[10][11]

In 2019, new IAAF (World Athletics) rules came into force for athletes like Semenya with certain disorders of sex development (DSDs) requiring medication to suppress testosterone levels in order to participate in 400m, 800m, and 1500m women's events. Semenya refused to undergo the treatment, which is now mandatory.[12] She has filed a series of legal cases to restore her ability to compete in these events without testosterone suppression, arguing that the World Athletics rules are discriminatory.[13]

Early life and education

[edit]Semenya was born in Ga-Masehlong, a village in South Africa near Polokwane, and grew up in the village of Fairlie in South Africa's northern Limpopo province. She has three sisters and a brother.[14][15]

Semenya attended Nthema Secondary School and the University of North West as a sports science student.[16][17] She began running as training for association football.[18]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Intersex condition

[edit]Although Semenya was assigned female at birth,[19][20] she has the intersex condition 5α-Reductase 2 deficiency (5-ARD).[10][11][19] This condition only affects genetic males with XY chromosomes. Individuals with 5-ARD have normal male internal structures that are not fully masculinised during the development of the reproductive system in utero, due to low levels of the hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT). As a result, the external genitalia may appear ambiguous or female at birth.[21][22][23]

Semenya has said that she was born with a vagina and internal undescended testes, but that she has no uterus or fallopian tubes and does not menstruate.[11][24][25] Her internal testes produce natural testosterone levels in the typical male range.[11][26] Semenya has rejected the label of "intersex", calling herself "a different kind of woman."[26]

Career

[edit]2008

[edit]In July, Semenya participated in the 2008 World Junior Championships in the 800 m and did not qualify for the finals. She won gold at the 2008 Commonwealth Youth Games with a time of 2:04.23.[27]

2009

[edit]

In the African Junior Championships, Semenya won both the 800 m and 1500 m races with the times of 1:56.72 and 4:08.01, respectively.[28][29] With that race she improved her 800 m personal best by seven seconds in less than nine months, including four seconds in that race alone.[16][30] The 800 m time was the world leading time in 2009 at that date.[30] It was also a national record and a championship record. Semenya simultaneously beat the Senior and Junior South African records held by Zelda Pretorius at 1:58.85, and Zola Budd at 2:00.90, respectively.[31]

In August, Semenya won gold in the 800 metres at the World Championships with a time of 1:55.45 in the final, again setting the fastest time of the year.[32]

In December 2009, Track and Field News voted Semenya the Number One Women's 800-metre runner of the year.[33]

Sex verification tests

[edit]Following her victory at the world championships, questions were raised about her sex.[16][30][34][35] Having beaten her previous 800 m best by four seconds at the African Junior Championships just a month earlier,[36] her quick improvements came under scrutiny. The combination of her rapid athletic progression and her appearance culminated in World Athletics (formerly called the IAAF) asking her to take a sex verification test to ascertain whether she was female.[37][38] The IAAF says it was "obliged to investigate" after she made improvements of 25 seconds at 1500 m and eight seconds at 800 m – "the sort of dramatic breakthroughs that usually arouse suspicion of drug use".[39]

The sex test results were never published officially, but some results were leaked in the press and were widely discussed, resulting in at the time unverified claims about Semenya having an intersex trait.[40][41]

In November 2009, South Africa's sports ministry issued a statement that Semenya[42] had reached an agreement with the IAAF to keep her medal and award.[43] Eight months later, in July 2010, she was cleared again to compete in women's competitions.[44][45]

Reaction

[edit]News that the IAAF requested the test broke three hours before the 2009 World Championships 800 m final.[30] IAAF president Lamine Diack stated, "There was a leak of confidentiality at some point and this led to some insensitive reactions."[46] The IAAF's handling of the case spurred many negative reactions.[47] A number of athletes, including retired sprinter Michael Johnson, criticised the organisation for its response to the incident.[48][49] There was additional outcry from South Africans, alleging undertones of European racism and imperialism embedded in the gender testing. Many local media reports highlighted these frustrations and challenged the validity of the tests with the belief that through Semenya's testing, members of the Global North did not want South Africans to excel.[50]

The IAAF said it confirmed the requirement for a sex verification test after the news had already been reported in the media, denying charges of racism and expressing regret about "the allegations being made about the reasons for which these tests are being conducted".[39][51] The federation also explained that the motivation for the test was not suspected cheating but a desire to determine whether she had a "rare medical condition" giving her an "unfair advantage".[52] The president of the IAAF stated that the case could have been handled with more sensitivity.[53]

On 7 September 2009, Wilfred Daniels, Semenya's coach with Athletics South Africa (ASA), resigned because he felt that ASA "did not advise Ms. Semenya properly". He apologised for personally having failed to protect her.[54] ASA President Leonard Chuene admitted on 19 September 2009 to having subjected Semenya to testing. He had previously lied to Semenya about the purpose of the tests and to others about having performed the tests. He ignored a request from ASA team doctor Harold Adams to withdraw Semenya from the World Championships over concerns about the need to keep her medical records confidential.[55]

Prominent South African civic leaders, commentators, politicians, and activists characterised the controversy as racist, as well as an affront to Semenya's privacy and human rights.[56][57] On the recommendation of South Africa's Minister for Sport and Recreation, Makhenkesi Stofile, Semenya retained the legal firm Dewey & LeBoeuf, acting pro bono, "to make certain that her civil and legal rights and dignity as a person are fully protected".[58][59][60] In an interview with South African magazine YOU Semenya stated, "God made me the way I am and I accept myself."[61] Following the furore, Semenya received great support within South Africa,[48][49] to the extent of being called a cause célèbre.[57]

2010

[edit]

In March 2010, Semenya was denied the opportunity to compete in the local Yellow Pages Series V Track and Field event in Stellenbosch, South Africa, because the IAAF had yet to release its findings from her sex test.[62]

On 6 July, the IAAF cleared Semenya to return to international competition.[63] The results of the sex tests, however, were not released for privacy reasons.[8] She returned to competition nine days later, winning two minor races in Finland.[64] On 22 August 2010, running on the same track as her World Championship victory, Semenya started slowly but finished strongly, dipping under 2:00 for the first time since the controversy, while winning the ISTAF meet in Berlin.[65]

Not being in full form, she did not enter the World Junior Championships or the African Championships, both held in July 2010, and opted to target the Commonwealth Games to be held in October 2010.[66] She improved her season's best to 1:58.16 at the Notturna di Milano meeting in early September and returned to South Africa to prepare for the Commonwealth Games.[67] Eventually, she was forced to skip the games due to an injury.[68]

2011

[edit]After the controversy of the previous year, Semenya returned to action with a moderately low profile, running only 1:58.61 at the Bislett Games as her best prior to the World Championships.[69] During the championships, she easily won her semi-final heat. In the final, she remained in the front of the pack leading into the final straightaway. While she separated from the rest of the field, Mariya Savinova followed her, then sprinted past Semenya before the finish line, leaving her to finish second.[69] In 2017, Savinova was banned for doping and her results were disqualified,[70] resulting in Semenya being awarded the gold medal.

2012 Olympics

[edit]

Caster Semenya was chosen to carry the country's flag during the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics.[71] She later won a silver medal in the women's 800 metres of these games, with a time of 1:57.23 seconds, her season's best. She passed six competitors in the last 150 metres, but did not pass world champion Mariya Savinova of Russia, who took gold in a time of 1:56.19, finishing 1.04 seconds before Semenya.[72] During the BBC coverage after the race, former British hurdler Colin Jackson raised the question whether Semenya had thrown the race, as the time that had been run was well within her capability,[73][74] though in fact Semenya had at that point only once in her life run faster than Savinova's winning time, when winning the 2009 World Championships.[75]

In November 2015, the World Anti-Doping Agency recommended Savinova and four other Russian athletes be given a lifetime ban for doping violations at the Olympics.[76] On 10 February 2017, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) officially disqualified Savinova's results backdated to July 2010. The International Olympic Committee reallocated the London 2012 medals, and Semenya's silver was upgraded to gold.[77][78][79]

2015 testosterone rule change

[edit]The IAAF policy on high natural levels of testosterone in women, that had been in place since 2011[80] was suspended following the case of Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations, in the Court of Arbitration for Sport, decided in July 2015.[81] The ruling found that there was a lack of evidence provided that testosterone increased female athletic performance and notified the IAAF that it had two years to provide the evidence.[82]

2016

[edit]On 16 April, Semenya became the first person to win all three of the 400 m, 800 m, and 1500 m titles at the South African National Championships, setting world leading marks of 50.74 and 1:58.45 in the first two events, and a 4:10.93 in the 1500 m, all within a nearly four-hour span of each other.[83][84]

On 16 July, she set a new national record for 800 metres of 1:55:33.[85][86] On 20 August, she won the gold medal in the women's 800 metres at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio with a time of 1:55.28.[87] The win reignited controversy over the rules on permissible testosterone levels; immediately after the race Lynsey Sharp, finishing sixth, broke into tears, having previously said that "everyone can see it's two separate races",[88] while fifth-placed Joanna Jóźwik stated "I feel like the silver medalist ... I'm glad I'm the first European, the second white", to finish the race.[89][90] Bioethicist Katrina Karkazis criticised the indignant response to Semenya's win as discriminatory.[90]

Semenya set a new personal best for the 400 m of 50.40 at the 2016 Memorial Van Damme track and field meet in Brussels.[91]

2017

[edit]Semenya won the bronze medal in the 1500 metres at the 2017 World Championships held in London.[92] She also won the gold medal in the women's 800m event.[93]

2018 testosterone rule change

[edit]In April 2018, the IAAF announced new rules effective 8 May 2019 that applied to athletes with certain disorders of sex development (DSDs) that result in androgen sensitivity and testosterone levels above 5 nmol/L. Under the new rules, these athletes would be required to take medication to lower their testosterone levels below the 5 nmol/L threshold for at least six months in order to compete in the female classification for certain events.[94][95][96][97]

In a report explaining its decision, the IAAF wrote that there was a "broad medical and scientific consensus" that athletes with high testosterone can "significantly enhance their sporting potential" due to greater muscle mass, strength, and haemoglobin levels. The report added that "there is no other genetic or biological trait encountered in female athletics that confers such a huge performance advantage."[98]

The IAAF's changes applied to eight different events—including the 400m, 800m, and 1500m, which Semenya regularly competed in.[99] Sports scientist Ross Tucker estimated that the new rules could make Semenya "five to seven seconds slower over 800 metres."[98] Female athletes without a DSD are not subject to any testosterone limits.[100]

2019 football career

[edit]In September 2019, Semenya joined the South African SAFA Sasol Women's League football club JVW F.C., owned by Janine van Wyk.[101]

Tokyo 2020 Olympics

[edit]In 2020, Semenya announced that she had decided to switch to the 200 meters for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, in order to avoid the 400 m to one mile ban.[102] In order to qualify for the 200 meters, Semenya would have needed to achieve the qualifying time of 22.80.[103] She had previously won the 5000 m at the South African championship in 2019.[104]

On 15 April 2021, Semenya confirmed she would not try to make the Tokyo 2020 200m qualifying standard.[105] On 28 May 2021, Semenya ran a personal best of 15:32.15 in the 5000m, 22 seconds slower than the necessary speed to compete at the Olympics.[106]

2022 World Championships

[edit]Semenya ran in the 5000 meter race at the 2022 World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon. It was her first major international competition since 2017. She finished almost a minute behind first place in her heat of the semifinals, and did not advance to the finals.[107]

Legal cases against World Athletics

[edit]In June 2018, Semenya announced that she would legally challenge the IAAF rules, calling them "discriminatory, irrational, [and] unjustifiable".[108] She claimed that testosterone-suppressing medication, which she had taken from 2010 to 2015, had made her feel "constantly sick" and caused her abdominal pain, and that the IAAF had used her as a "guinea pig" to test the medication's effects.[109]

The case divided both legal and scientific commentators. Duke Law School professor and former middle-distance runner Doriane Lambelet Coleman argued that the organization's rules guaranteed a "protected space" for female athletes. Physician and genetics researcher Eric Vilain argued in favor of Semenya, claiming that "sex is not defined by one particular parameter... it's so difficult to exclude women who've always lived their entire lives as women."[110] During the proceedings, the IAAF clarified that the regulations would only apply to DSD athletes with XY chromosomes.[99][111]

In May 2019, the Court of Arbitration for Sport rejected Semenya's challenge in a 2–1 decision, paving the way for the new rules to come into effect. Although the CAS agreed with Semenya that the rules were discriminatory, it concluded that this discrimination was "a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the IAAF's aim of preserving the integrity of female athletics".[112][113]

That same month, Semenya appealed the decision to the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland. The court provisionally suspended the World Athletics rules while deciding whether to issue an interlocutory injunction in June.[114] However, this decision was reversed in July, leaving Semenya unable to compete in World Athletics races between 400m and one mile while her appeal continued.[115]

The Swiss supreme court ultimately dismissed Semenya's appeal in September 2020. In its decision, the court affirmed that the CAS had the right to uphold World Athletics' rules "in order to guarantee fair competition for certain running disciplines in female athletics."[116] The court also declared that because Semenya was "free to refuse treatment to lower testosterone levels," her "guarantee of human dignity" was not violated.[117]

In February 2021, Semenya appealed the case to the European Court of Human Rights.[118] In March 2023, World Athletics made its rules for Semenya and other DSD athletes even more restrictive, requiring them to lower their testosterone levels below a threshold of 2.5 nmol/L for at least 24 months before competing.[119] The ECHR ruled in Semenya's favor in a 4–3 decision in July 2023, finding that the competition rules had discriminated against her and infringed on her human rights. However, the decision did not overturn the rules themselves, and World Athletics stated that the regulations would "remain in place."[120]

After a request from the Swiss government, Semenya's case was referred to the ECHR's Grand Chamber in November 2023 for a final ruling.[121]

Competition record

[edit]| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 800m world rank: NR |

World Junior Championships | Bydgoszcz, Poland | 7th (h) | 800 m | 2:11.98 |

| Commonwealth Youth Games | Pune, India | 1st | 800 m | 2:04.23 GR | |

| 2009 800m world rank: 1st[122] |

South African Championships | Stellenbosch, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:03.16 |

| 2nd | 1500 m | 4:16.43 | |||

| South African U18/U20 Championships | Pretoria, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:02.00 | |

| 1st | 1500 m | 4:25.70 | |||

| African Junior Championships | Bambous, Mauritius | 1st | 800 m | 1:56.72 NR CR | |

| 1st | 1500 m | 4:08.01 | |||

| IAAF World Championships | Berlin, Germany | 1st | 800 m | 1:55.45 | |

| IAAF formalizes testosterone policy[123] | |||||

| 2011 800m world rank: 2nd |

South African Championships | Durban, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:02.10 |

| 1st | 1500 m | 4:12.93 | |||

| 1st | 4 × 400 m | 3:41.30 | |||

| IAAF World Championships | Daegu, South Korea | 1st | 800 m | 1:56.35[cr 1] | |

| 2012 800m world rank: 5th |

South African Championships | Port Elizabeth, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:02.68 |

| 1st | 4 × 400 m | 3:36.92 | |||

| Olympic Games | London, United Kingdom | 1st | 800 m | 1:57.23[cr 1] | |

| 2014 800m world rank: NR |

South African Championships | Pretoria, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:03.05 |

| 2015 800m world rank: NR |

South African Championships | Stellenbosch, South Africa | 1st | 800 m | 2:05.05 |

| 8th | 1500 m | 4:29.60 | |||

| IAAF World Championships | Beijing, China | 8th (h) | 800 m | 2:03.18 | |

| All-Africa Games | Brazzaville, Congo | 1st | 800 m | 2:00.97 | |

| 8th | 1500 m | 4:23.00 | |||

| Court of Arbitration in Sport temporarily lifts testosterone regulations[124] | |||||

| 2016 800m world rank: 1st |

South African Championships | Stellenbosch, South Africa | 1st | 400 m | 50.74 |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:58.45 | |||

| 1st | 1500 m | 4:10.91 | |||

| African Championships | Durban, South Africa | 1st | 1500 m | 4:01.99 | |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:58.20 | |||

| 1st | 4 × 400 m | 3:28.49 | |||

| Olympic Games | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 1st | 800 m | 1:55.28 NR | |

| 2017 800m world rank: 1st |

South African Championships | Potchefstroom, South Africa | 1st | 400 m | 51.60 |

| 1st | 800 m | 2:01.03 | |||

| IAAF World Championships | London, United Kingdom | 3rd | 1500 m | 4:02.90 | |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:55.16 | |||

| IAAF reinstates testosterone rules[125] | |||||

| 2018 800m world rank: 1st |

South African Championships | Pretoria, South Africa | 1st | 1500 m | 4:10.68 |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:57.80 | |||

| Commonwealth Games | Gold Coast, Australia | 1st | 1500 m | 4:00.71 GR | |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:56.68 GR | |||

| African Championships | Asaba, Nigeria | 1st | 400 m | 49.96 | |

| 1st | 800 m | 1:56.06 CR | |||

| 2019 | South African Championships | Germiston, South Africa | 1st | 5000 m | 16:05.97 |

| 1st | 1500 m | 4:13.59 | |||

| 2022[126] | World Athletics Championships | Eugene, Oregon | 13th in semifinals | 5000 m | 15:46.12 |

- ^ a b In the 2011 World Championships and the 2012 Olympic Games, Semenya finished 2nd to Mariya Savinova, but Savinova was later disqualified due to failing an antidoping test, promoting Semenya to the gold medal in both races.

Works

[edit]- Semenya, Caster (31 October 2023). The Race to Be Myself. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-1-324-03577-0. [127][128][129]

Personal life and honours

[edit]In 2010, the British magazine New Statesman included Semenya in its annual list of "50 People That Matter" for unintentionally instigating "an international and often ill-tempered debate on gender politics, feminism, and race, becoming an inspiration to gender campaigners around the world".[130]

In 2012, Semenya was awarded South African Sportswoman of the Year Award at the SA Sports Awards in Sun City. Semenya received the bronze Order of Ikhamanga on 27 April 2014, as part of Freedom Day festivities.[131]

Semenya married her long-term partner, Violet Raseboya, in December 2015 (traditional ceremony) and January 2017 (civil ceremony).[132][133][134] They have two daughters, one born in 2019 and another in 2022.[135] Their first daughter was conceived through artificial insemination.[136]

In October 2016, the IAAF announced that Semenya was shortlisted for women's 2016 World Athlete of the Year.[137]

Semenya was named one of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People of 2019.[138]

Semenya was one of the athletes whose cases were profiled in Phyllis Ellis's 2022 documentary film Category: Woman.[139]

On 31 October 2023, Semenya's memoir, The Race to Be Myself, was published by #Merky Books (an imprint of Penguin Random House UK).[140][141] In The Guardian, Emma John wrote that Semenya's "timely, sometimes angry memoir inspires compassion" while acknowledging that it presented mainly her side of the controversy about her running career.[142] The book was named a New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice in December 2023.[143]

See also

[edit]- Dutee Chand

- Imane Khelif

- Ewa Kłobukowska

- Maria José Martínez-Patiño

- Francine Niyonsaba

- Santhi Soundarajan

- Margaret Wambui

- List of intersex Olympians

References

[edit]- ^ "Caster Semenya Runs 1:54.25 with No Rabbits to Become 4th Fastest Ever and Destroy World's Best in Paris". LetsRun.com. 30 June 2018.

- ^ Written at Berlin. "Semenya clocks 2:30.70 in ISTAF 1000m as Harting takes his final bow". Monaco: IAAF. 2 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "IAAF Diamond League | Doha (QAT) | 4 May 2018" (PDF). static.sportresult.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Caster Semenya Biography, Olympic Medals, Records and Age". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Rio Olympics 2016: Caster Semenya wins 800m gold for South Africa". BBC Sport. BBC. 21 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Caster Semenya awarded gold for 800m at 2012 London Games". eNCA. 10 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Caster Semenya given London 2012 gold medal after rival is stripped of title". The Guardian. 10 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Semenya cleared to return to track immediately". Associated Press. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Kessel, Anna (6 July 2010). "Caster Semenya may return to track this month after IAAF clearance". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ a b Ingle, Sean (18 June 2019). "Caster Semenya accuses IAAF of using her as a 'guinea pig experiment'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Caster Semenya Q&A: Who is she and why is her case important?". BBC Sport. 15 November 2023. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Hernandez, Erica (6 November 2023). "Caster Semenya says she went through 'hell' due to testosterone limits imposed on female athletes". CNN. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ "Caster Semenya Opens Up About Discrimination Battle Against World Athletics". 2 November 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Abrahamson, Alan (20 August 2009). "Caster Semenya's present and future". Universal Sports. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "Athletics-Olympic hope Semenya runs fastest 400 metres of year". 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Slot, Owen (19 August 2009). "Caster Semenya faces sex test before she can claim victory". The Times. London. Retrieved 20 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Lucas, Ryan (22 August 2009). SAfrican in gender flap gets gold for 800 win[dead link] www.wistv.com. Associated Press.

- ^ Prince, Chandre (29 August 2009). "Hero Caster's road to gold". The Times. Retrieved 30 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b Ingle, Sean (21 July 2022). "Caster Semenya out of world 5,000m as Coe signals tougher female sport rules". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Birth certificate backs SA gender". BBC News. 21 August 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Randall, Valerie Anne (1994). "9 Role of 5α-reductase in health and disease". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 8 (2): 405–431. doi:10.1016/S0950-351X(05)80259-9. ISSN 0950-351X. PMID 8092979. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Okeigwe, Ijeoma; Kuohung, Wendy (December 2014). "5-Alpha reductase deficiency: a 40-year retrospective review". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity. 21 (6): 483–487. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000116. ISSN 1752-296X. PMID 25321150.

- ^ "5-alpha reductase deficiency: MedlinePlus Genetics". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Golodryga, Bianna; Church, Ben; Hullah, Henry (6 November 2023). "Caster Semenya says she went through 'hell' due to testosterone limits imposed on female athletes". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Semenya, Caster (28 October 2023). "'You are not here for a doping test. You are here for a gender test': athlete Caster Semenya on how her life changed for ever". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b Semenya, Caster (21 October 2023). "Running in a Body That's My Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Young SA team strikes gold". Independent Online. 16 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ouma, Mark (2 August 2009). "Nigerian Ogoegbunam completes a hat trick at Africa Junior Championships". AfricanAthletics.org. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Ouma, Mark (31 July 2009). "South African teen Semenya stuns with 1:56.72 800m World lead in Bambous – African junior champs, Day 2". IAAF. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Tom Fordyce (19 August 2009). "Semenya left stranded by storm". BBC Sport. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ South African teen Semenya stuns with 1:56.72 800m World lead in Bambous – African junior champs, Day 2 IAAF, 31 July 2009.

- ^ "800 Metres Women Final Results" (PDF). 19 August 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Track and Field News, Vol 8. Number 59, 22 December 2009.

- ^ Women's world champion Semenya faces gender test CNN, 20 August 2009.

- ^ "Semenya told to take gender test". BBC Sport. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ Ouma, Mark (31 July 2009). South African teen Semenya stuns with 1:56.72 800m World lead in Bambous – African junior champs, Day 2. IAAF. Retrieved on 22 August 2009. Archived 8 September 2009.

- ^ "STATEMENT ON CASTER SEMENYA- News - iaaf.org". www.iaaf.org.

- ^ Smith, David (20 August 2009). Caster Semenya sex row: 'She's my little girl,' says father. The Guardian. Retrieved on 22 August 2009.

- ^ a b David Smith, "Caster Semenya row: 'Who are white people to question the makeup of an African girl? It is racism'" The Observer, 23 August 2009.

- ^ Farndale, Nigel (25 October 2009). "Athletics: Caster Semenya the latest female athlete suspected of being biological male". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Padawer, Ruth (28 June 2016). "The Humiliating Practice of Sex-Testing Female Athletes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Caster Semenya Strong Finish Women's 400m | Brussels Diamond League Archived 13 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 10 September 2016.

- ^ Jere Longman "South African Runner’s Sex-Verification Result Won’t Be Public" The New York Times, 19 November 2009.

- ^ "Caster Semenya given all clear after gender test row". The Daily Telegraph. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Caster Semenya coasted to victory in the Monaco meeting". 16 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Hart, Simon (24 August 2009). "World Athletics: Caster Semenya tests 'show high testosterone levels'". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Linda Geddes, Scant support for sex test on champion athlete New Scientist, 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Semenya dismissive of gender row". BBC Sport. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b "South Africans unite behind gender row athlete". BBC News. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Dworkin, Shair (2012). "The (Mis)Treatment of South African Track Star Caster Semenya". Sexual Diversity in Africa: Politics, Theory, and Citizenship: 129–148.

- ^ "SA to take up Semenya case with UN", The Times SA, 21 August 2009 [dead link]

- ^ "SA fury over athlete gender test". BBC Sport. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "New twist in Semenya gender saga". BBC Sport. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "S. Africa gender row coach resigns". BBC News. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Serena Chaudhry (19 September 2009). "South Africa athletics chief admits lying about Semenya tests". Reuters. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn (26 August 2009). "Caster Semenya, South African runner subjected to gender test, gets tumultuous welcome home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b Sawer, Patrick; Berger, Sebastian (23 August 2009). "Gender row over Caster Semenya makes athlete into a South African cause celebre". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Dewey takes up Semenya case in IAAF dispute – Legalweek Magazine

- ^ Dewey & LeBoeuf to advise Caster Semenya – The Times Archived 25 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dewey & LeBoeuf Retained to Protect Rights of South African Runner Caster Semenya Archived 16 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine – press release from Dewey & LeBoeuf.

- ^ "Makeover for SA gender-row runner". BBC News. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "Semenya announces return to competitive running". NBC Sports. Retrieved 30 March 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Kessel, Anna (6 July 2010). "Caster Semenya may return to track this month after IAAF clearance". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Yahoo News, 18 July 2010: Semenya easily wins again in Finland [dead link]

- ^ AP article Archived 24 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CBC, 21 July 2010: Semenya has eyes on Commonwealth Games

- ^ Sampaolo, Diego (10 September 2010). Howe, Semenya, and Yenew highlight in Milan. IAAF. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Injured Semenya pulls out of Commonwealth Games", The Hindu, 29 September 2010:

- ^ a b "2011 Oslo Bislett Games Results". letsrun.com. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Payne, Marissa. "Russian runner who admitted on video to doping is stripped of Olympic gold". washingtonpost.com. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Caster Semenya rightly chosen to bear South Africa's flag at opening ceremony". CBS Sports. 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Caster clinches silver medal". Sport24. 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Semenya: 'I tried my best': South African silver medallist hits back at allegations she did not try to win 800-metre race at the Olympics". Al Jazeera. 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Olympic Games – Semenya denies trying not to win Olympic title". Yahoo Sport. 14 August 2012.

- ^ "All-time women's best 800 m". Track and Field all-time. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Owen (9 November 2015). "Russia accused of 'state-sponsored doping' as Wada calls for athletics ban". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Mariya Savinova: Russian London 2012 gold medallist stripped of title". BBC. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "IOC ready to strip medals from Russians". TSN. 10 November 2015.

- ^ "London 2012 800m women – Olympic Athletics". International Olympic Committee. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "What is an intersex athlete? Explaining the case of Caster Semenya". The Guardian. 29 July 2016.

- ^ Court of Arbitration for Sport (July 2015). CAS 2014/A/3759 Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) (PDF). Court of Arbitration for Sport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Branch, John (27 July 2016). "Dutee Chand, Female Sprinter With High Testosterone Level, Wins Right to Compete". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport, based in Switzerland, questioned the athletic advantage of naturally high levels of testosterone in women and therefore immediately suspended the practice of 'hyperandrogenism regulation' by track and field's governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations. It gave the organization, known as the I.A.A.F., two years to provide more persuasive scientific evidence linking 'enhanced testosterone levels and improved athletic performance'.

- ^ "Semenya makes history at nationals". Sport24. 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Caster Semenya South African National Olympic Trials 1500 meters results". Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "Rio Olympics 2016: Caster Semenya wins 800m gold for South Africa". BBC Sport. bbc.com. 21 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Caster SEMENYA | Profile". worldathletics.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Blumenthal, Scott (20 August 2016). "Rio Olympics: Caster Semenya Leaves No Doubt in 800". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Samuel (22 August 2016). "Rio 2016: Caster Semenya victory in 800m reduces Team GB athlete Lynsey Sharp to tears". The Independent. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Critchley, Mark (22 August 2016). "Fifth-placed runner behind Semenya 'feels like silver medalist' and glad she was the 'second white'". The Independent. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ a b Karkazis, Katrina. "The ignorance aimed at Caster Semenya flies in the face of the Olympic spirit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "Results: 2016 Memorial Van Damme / Brussels Diamond League Results". LetsRun.com. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "1500 Metres Women − Final − Results" (PDF). IAAF. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "800 Metres Women − Final − Results" (PDF). IAAF. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Bloom, Ben (25 April 2018). "Caster Semenya to be forced to lower testosterone levels or face 800m ban". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Caster Semenya expected to be affected by IAAF rule changes". BBC Sport. 26 April 2018.

- ^ "IAAF introduces new eligibility regulations for female classification". Monaco: IAAF. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "IAAF Eligibility Regulations for the Female Classification (Athletes with Differences of Sex Development) in force as from 8 May 2019". 1 June 2019.

- ^ a b Ingle, Sean (26 April 2018). "New IAAF testosterone rules could slow Caster Semenya by up to seven seconds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b Court of Arbitration for Sport (1 May 2019), Semenya, ASA and IAAF: Executive Summary (PDF), retrieved 1 June 2019,

During the course of the proceedings before the CAS, the IAAF explained that, following an amendment to the DSD Regulations, the DSD covered by the Regulations are limited to "46 XY DSD" – i.e. conditions where the affected individual has XY chromosomes. Accordingly, no individuals with XX chromosomes are subjected to any restrictions or eligibility conditions under the DSD Regulations

- ^ Epstein, David (18 September 2020). "Why I Changed My Mind About the Caster Semenya Case". Slate. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Reporter, Phakaaathi (5 September 2019). "Caster Semenya joins football club – reports". The Citizen. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Caster Semenya says she will switch distances to the 200m in bid to qualify for Tokyo Olympics". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 March 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Mjikeliso, Sibusiso (19 May 2020). "Caster Semenya to 'stick to 200m no matter what'". www.news24.com. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Written at Germiston, South Africa. "Athletics: Semenya wins 5,000m gold at South African Championships". London: Reuters. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Tokyo 2020: Caster Semenya confirms she will not attempt 200m Olympics qualification". Sky Sports. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Caster Semenya misses out on 5000m Olympic qualifying time in Durban". Olympics.com. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Caster Semenya unnoticed at World Championships". MSN. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Longman, Jeré (18 June 2018). "Caster Semenya Will Challenge Testosterone Rule in Court". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (18 June 2019). "Caster Semenya accuses IAAF of using her as a 'guinea pig experiment'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Block, Melissa (31 May 2019). "'I Am A Woman': Track Star Caster Semenya Continues Her Fight To Compete As Female". NPR. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "IAAF told to suspend Semenya testosterone rules", 3 June 2019, ESPN.

- ^ "Caster Semenya: Olympic 800m champion loses appeal against IAAF testosterone rules". BBC News. 1 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (1 May 2019). "Semenya loses landmark legal case against IAAF over testosterone levels". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Caster Semenya: Olympic 800m champion can compete after Swiss court ruling". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Mather, Victor; Longman, Jeré (31 July 2019). "Ruling Leaves Caster Semenya With Few Good Options". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Caster Semenya loses appeal over testosterone rule". NBCSports. 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Dunbar, Graham; Inmay, Gerald (8 September 2020). "Semenya loses at Swiss supreme court over testosterone rules". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Spary, Sara (26 February 2021). "Caster Semenya appeals to European Court of Human Rights over 'discriminatory' testosterone limit". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Ewing, Lori (23 March 2023). "World governing body bans transgender women athletes". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Olympic champion Caster Semenya wins appeal against testosterone rules in human rights court". NBC News. Associated Press. 11 July 2023. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ "Semenya case referred to European rights court's grand chamber". Reuters. 6 November 2023. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "Track & Field News World Rankings: Women's 800m" (PDF). Track & Field News. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "IAAF approves new rules on hyperandrogenism". The Guardian. 12 April 2011.

- ^ Matt Slater (28 July 2015). "Sport & gender: A history of bad science & 'biological racism'". BBC Sport.

- ^ Aimee Lewis (26 April 2018). "Caster Semenya may have to reduce hormone levels to compete at Olympics". CNN.

- ^ "Caster Semenya unnoticed at World Championships". MSN.

- ^ Miller, Jen A. (31 October 2023). "Book Review: 'The Race to Be Myself,' by Caster Semenya". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ John, Emma (5 November 2023). "The Race to Be Myself by Caster Semenya review – running for her life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Olympic runner Caster Semenya's memoir tackles gender stereotypes in sports : NPR's Book of the Day". NPR. 9 January 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Caster Semenya – 50 people that matter 2010". Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Zuma presents National Orders in Pretoria". eNCA. 27 April 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Caster Semenya has stirring words for her critics after winning women's 800m". Sydney Morning Herald. 21 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "WATCH: Caster on love, Rio and playing for Banyana". The Sunday Times. 24 April 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Faeza (9 January 2017). "PICTURES: Caster Semenya and Violet Raseboya's are now married". News24. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Caster Semenya's wife: 5 interesting facts and photos of Violet Raseboya". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Engelbrecht, Compiled by Leandra. "Caster Semenya and wife Violet celebrate 'miracle' baby on third birthday". Life. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Nominees announced for World Athlete of the Year". IAAF. 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Caster Semenya: The 100 Most Influential People of 2019". TIME. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "New Canadian documentary explores Caster Semenya story in human-rights terms". Canadian Running, April 29, 2022.

- ^ Shaffi, Sarah (2 June 2023). "Caster Semenya to publish 'unflinching' memoir with Stormzy's #Merky Books". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Miller, Jen A. (31 October 2023). "Caster Semenya: 'I'm Still a Woman'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ John, Emma (5 November 2023). "The Race to Be Myself by Caster Semenya review – running for her life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "7 New Books We Recommend This Week". The New York Times. 14 December 2023. Archived from the original on 18 February 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1991 births

- Living people

- Sportspeople from Polokwane

- South African female middle-distance runners

- Olympic female middle-distance runners

- Olympic athletes for South Africa

- Olympic gold medalists for South Africa

- Olympic gold medalists in athletics (track and field)

- Athletes (track and field) at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Athletes (track and field) at the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Commonwealth Games gold medallists for South Africa

- Commonwealth Games medallists in athletics

- Athletes (track and field) at the 2018 Commonwealth Games

- African Games gold medalists for South Africa

- African Games medalists in athletics (track and field)

- Athletes (track and field) at the 2015 African Games

- World Athletics Championships athletes for South Africa

- World Athletics Championships medalists

- Recipients of the Order of Ikhamanga

- Sex verification in sports

- University of Pretoria alumni

- Northern Sotho people

- South African lesbian sportswomen

- LGBTQ track and field athletes

- Intersex women

- Intersex sportspeople

- Track & Field News Athlete of the Year winners

- World Athletics Championships winners

- South African women's soccer players

- South African LGBTQ footballers

- African Championships in Athletics winners

- IAAF Continental Cup winners

- Diamond League winners

- South African Athletics Championships winners

- Commonwealth Games gold medallists in athletics

- 21st-century South African LGBTQ people

- Medallists at the 2018 Commonwealth Games

- North-West University alumni

- Lesbian memoirists