Bulgarian Front of First Balkan War

| Bulgarian Front of First Balkan War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First Balkan War | |||||||

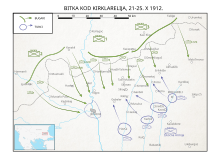

Clockwise, from top left: Battle of Kardzhali, Battle of Kirk Kilisse, Battle of Lule Burgas, Bulgarian officers in Çatalca | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Bulgarian Front of First Balkan War was one of the heaviest fronts of the First Balkan War fought between 21 October 1912 and 3 April 1913

Background

[edit]Tensions among the Balkan states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of Ottoman-controlled Rumelia (Eastern Rumelia, Thrace and Macedonia) subsided somewhat after the mid-19th-century intervention by the Great Powers, which aimed to secure both more complete protection for the provinces' Christian majority as well as to maintain the status quo. By 1867, Serbia and Montenegro had both secured their independence, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). The question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the Young Turk Revolution in July 1908, which compelled the Ottoman Sultan to restore the suspended constitution of the empire.

Serbia's aspirations to take over Bosnia and Herzegovina were thwarted by the Bosnian crisis, which led to the Austrian annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then directed their war efforts to the south. After the annexation, the Young Turks tried to induce the Muslim population of Bosnia to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman authorities resettled those who took up the offer in districts of northern Macedonia with few Muslims. The experiment proved to be a catastrophe since the immigrants readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims and participated in the series of 1911 Albanian uprisings and the Albanian revolt of 1912. Some Albanian government troops switched sides.

In May 1912, Albanian rebels seeking national autonomy and the re-installment of Sultan Abdul Hamid II to power drove the Young Turkish forces out of Skopje and pressed south towards Manastir (now Bitola), forcing the Young Turks to grant effective autonomy over large regions in June 1912.[4][5] Serbia, which had helped the arming of Catholic Albanians in the Mirditë region and Hamidian rebels and sent secret agents to some of the prominent leaders, took the revolt as a pretext for war.[6] Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, and Bulgaria had all been in talks about possible offensives against the Ottoman Empire before the 1912 Albanian revolt had broken out, and a formal agreement between Serbia and Montenegro had been signed on 7 March. On 18 October 1912, King Peter I of Serbia issued a declaration, 'To the Serbian People,' which appeared to support Albanians as well as Serbs:

The Turkish governments showed no interest in their duties towards their citizens and turned a deaf ear to all complaints and suggestions. Things got so far out of hand that no one was satisfied with the situation in Turkey in Europe. It also became unbearable for the Serbs, the Greeks, and the Albanians. By the grace of God, I have therefore ordered my brave army to join in the Holy War to free our brethren and to wish for a better future. In Old Serbia, my army will meet not only upon Christian Serbs but also upon Muslim Serbs, who are equally dear to us, and in addition to them, upon Christian and Muslim Albanians with whom our people have shared joy and sorrow for thirteen centuries now. To all of them, we bring freedom, brotherhood and equality.

In a search for allies, Serbia was ready to negotiate a treaty with Bulgaria.[7] The agreement provided that in the event of victory against the Ottomans, Bulgaria would receive all of Macedonia south of the Kriva Palanka–Ohrid line. Bulgaria accepted Serbia's expansion as being to the north of the Shar Mountains (Kosovo). The intervening area was agreed to be "disputed" and would be arbitrated by the Tsar of Russia in the event of a successful war against the Ottoman Empire. During the war, it became apparent that the Albanians did not consider Serbia as a liberator, as had been suggested by King Peter I, and the Serbian forces failed to observe his declaration of amity toward Albanians.

After the successful coup d'état for unification with Eastern Rumelia,[8] Bulgaria began to dream that its national unification would be realized. For that purpose, it developed a large army and was identified as the "Prussia of the Balkans."[9] However, Bulgaria could not win a war alone against the Ottomans.

In Greece, Hellenic Army officers had rebelled in the Goudi coup of August 1909 and secured the appointment of a progressive government under Eleftherios Venizelos, which they hoped would resolve the Crete question in Greece's favour. They also wanted to reverse their defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1897) by the Ottomans. An emergency military reorganization, led by a French military mission, had been started for that purpose, but its work was interrupted by the outbreak of war in the Balkans. In the discussions that led to Greece joining the Balkan League, Bulgaria refused to commit to any agreement on distributing territorial gains, unlike its deal with Serbia over Macedonia. Bulgaria's diplomatic policy was to push Serbia into one that limited its access to Macedonia[10] while simultaneously refusing any such agreement with Greece. Bulgaria believed that its army could occupy the big part of Aegean Macedonia and the port city of Salonica (Thessaloniki) before the Greeks could do so.

In 1911, Italy had launched an invasion of Tripolitania, now in Libya, which was quickly followed by the occupation of the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea. The Italians' decisive military victories over the Ottoman Empire and the successful 1912 Albanian revolt encouraged the Balkan states to imagine that they might win a war against the Ottomans. By the spring and summer of 1912, the various Christian Balkan nations had created a network of military alliances, becoming known as the Balkan League.

The Great Powers, most notably France and Austria-Hungary, reacted to the formation of the alliances by trying unsuccessfully to dissuade the Balkan League from going to war. In late September, the League and the Ottoman Empire mobilized their armies. Montenegro was the first to declare war on 25 September (O.S.)/8 October. After issuing an impossible ultimatum to the Ottoman Porte on 13 October, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece declared war on the Ottomans on 17 October (1912). The declarations of war attracted a large number of war correspondents. An estimated 200 to 300 journalists from around the world covered the war in the Balkans in November 1912.[11]

Order of battle and plans

[edit]Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria was militarily the most powerful of the four Balkan states, with a large, well-trained, well-equipped army. Bulgaria mobilized a total of 599,878 men out of a population of 4.3 million. The Bulgarian field army counted for nine infantry divisions, one cavalry division and 1,116 artillery units. The commander-in-chief was Tsar Ferdinand, and the operating command was in the hands of his deputy, General Mihail Savov. The Bulgarians also had a small navy of six torpedo boats restricted to operations along the country's Black Sea coast.

Bulgaria was focused on actions in Thrace and Macedonia. It deployed its main force in Thrace by forming three armies. The First Army (79,370 men), under General Vasil Kutinchev, had three infantry divisions and was deployed to the south of Yambol and assigned operations along the Tundzha River. The Second Army (122,748 men), under General Nikola Ivanov, with two infantry divisions and one infantry brigade, was deployed west of the First Army and was assigned to capture the strong fortress of Adrianople (Edirne). Plans had the Third Army (94,884 men), under General Radko Dimitriev, to be deployed east of and behind the First Army and to be covered by the cavalry division that hid it from the Ottomans' sight. The Third Army had three infantry divisions and was assigned to cross Mount Stranja and to take the fortress of Kirk Kilisse (Kırklareli). The 2nd (49,180) and 7th (48,523 men) Divisions were assigned independent roles, operating in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia, respectively.

Ottoman Empire

[edit]In 1912, the Ottomans were in a difficult position. They had a large population, 26 million, but just over 6.1 million of them lived in its European part, only 2.3 million being Muslims. The rest were Christians, who were considered unfit for conscription. The poor transport network, especially in the Asian section, dictated that the only reliable way to mass transfer troops to the European theatre was by sea, but that faced the risk of the Greek fleet in the Aegean Sea. In addition, the Ottomans were still engaged in a protracted war against Italy in Libya (and by now in the Dodecanese islands of the Aegean), which had dominated the Ottoman military effort for over a year. The conflict lasted until 15 October, a few days after the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans. The Ottomans couldn't reinforce their positions in the Balkans meaningfully as their relations with the Balkan states deteriorated over the year

The Battles

[edit]Battle of Kardzhali

[edit]The Battle of Kircaali or Battle of Kardzhali was part of the First Balkan War between the armies of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. It took place on 21 October 1912, when the Bulgarian Haskovo Detachment defeated the Ottoman Kırcaali Detachment of Yaver Pasha and permanently joined Kardzhali and the Eastern Rhodopes to Bulgaria. The anniversary of that event is celebrated annually on 21 October as a holiday of the city.[12] Shortly before the war between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire, the 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Thracian Infantry Division (28th and 40th Infantry Regiments, reinforced by the 3rd Artillery Regiments was deployed in the area around Haskovo and had orders to cover the routes to Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. After the correction of the Bulgarian-Ottoman border in 1886 following the Unification of Bulgaria, the Ottomans controlled Kardzhali and the surrounding mountain ridges. Their army in the region was dangerously close to the railway between Plovdiv and Harmanli and the base of the Bulgarian armies which were to advance into Eastern Thrace. The commander of the 2nd Army General Nikola Ivanov ordered Delov to push the Ottomans to the south of the Arda river.[13][14]

The Bulgarian Haskovo Detachment numbered 8,700 soldiers with 42 guns.[15] and opposed the Ottoman Kırcaali Reserve Division (Kırcaali Redif Fırkası) and in the west the left group of the Bulgarian Rodopo Detachment opposed the Ottoman Kırcaali Home Guard Division (Kırcaali Müstahfız Fırkası) that were the parts of the Ottoman Kırcaali Detachment under Yaver Pasha, which was much larger (24,000[13]) but was dispersed and with fewer artillery pieces.[16] On the first day of the war, 18 October 1912, Delov's detachment advanced south across the border in four columns. The next day, they defeated the Ottoman troops at the villages of Kovancılar (present day: Pchelarovo) and Göklemezler (present day: Stremtsi) and then headed for Kardzhali. The detachment of Yaver Pasha left the town in disorder. With its advance towards Gumuljina, the Haskovo detachment threatened communications between the Ottoman armies in Thrace and Macedonia. For this reason, the Ottomans ordered Yaver Pasha to counter-attack before the Bulgarians could reach Kardzhali but did not send him reinforcements.[17] To follow this order he had in command 9 tabors and 8 guns.[16]

However, the Bulgarians were not aware of the strength of the enemy and on 19 October the Bulgarian High Command (the Headquarters of the Active Army under General Ivan Fichev) ordered General Ivanov to stop the advance of the Haskovo Detachment because it was considered risky. The commander of the 2nd Army, however, did not withdraw his orders and gave Delov freedom of action.[14] The detachment continued with the advance on 20 October. The march was slowed by the torrential rains and the slow movement of the artillery but the Bulgarians reached the heights to the north of Kardzhali before the Ottomans could reorganize.[18]

In the early morning of 21 October Yaver Pasha engaged the Bulgarians in the outskirts of the town. Due to their superior artillery and attacks on bayonet the soldiers of the Haskovo Detachment overran the Ottoman defenses and prevented their attempts to outflank them from the west. The Ottomans were in turn vulnerable to outflanking from the same direction and had to retreat for a second time to the south of the Arda River, leaving behind large quantities of munitions and equipment. At 16:00 the Bulgarians entered Kardzhali.[19] As a result of the battle most of the population left the town. The Turkish inhabitants of the area fled during the Bulgarian advance.

The defeated Ottomans retreated to Mestanlı (present day: Momchilgrad), while the Haskovo Detachment prepared defenses along the Arda. Thus the flank and the rear of the Bulgarian armies advancing towards Adrianople and Constantinople were secured. Concerned that after the fall of Kardzhali the Bulgarians would cut off the railway between Salonika and Dedeagach, the Ottoman High Command decided to distract the Bulgarians. Its haste orders for counter-attack of the Eastern Army led to the crushing defeat of the Ottomans in the Battle of Kirk Kilisse. The Bulgarian command did not proceed with the advance after the fall of Kardzhali. Instead of taking Gumuljina, on 23 October the main forces of the Haskovo Datachment were ordered to go east and participate in the siege of Adrianople. Only a small squad was left in Kardzhali.[20]

Battle of Kirk Kilisse

[edit]The Battle of Kirk Kilisse or Battle of Kirklareli[21] or Battle of Lozengrad was part of the First Balkan War between the armies of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. It took place on 24 October 1912, when the Bulgarian army defeated an Ottoman army in Eastern Thrace and occupied Kırklareli.

The initial clashes were around several villages to the north of the town. The Bulgarian attacks were irresistible and the Ottoman forces were forced to retreat. On 10 October the Ottoman army threatened to split 1st and 3rd Bulgarian armies but it was quickly stopped by a charge by 1st Sofian and 2nd Preslav brigades. After bloody fighting along the whole town front the Ottomans began to pull back and on the next morning Kırk Kilise (Lozengrad) was in Bulgarian hands. The Muslim Turkish population of the town was expelled and fled eastwards towards Constantinople.

Battle of Lule Burgas

[edit]The Battle of Lule Burgas (Turkish: Lüleburgaz Muharebesi) or Battle of Luleburgas – Bunarhisar (Bulgarian: Битка при Люлебургас – Бунархисар, Turkish: Lüleburgaz – Pınarhisar Muharebesi) was a battle between the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire and was the bloodiest battle of the First Balkan War. The battle took place from 28 October to 2 November 1912. The outnumbered Bulgarian forces made the Ottomans retreat to Çatalca line, 30 km from the Ottoman capital Constantinople. In terms of forces engaged it was the largest battle fought in Europe between the end of the Franco-Prussian War and the beginning of the First World War.[22] Following the quick Bulgarian victory on the Petra – Seliolu – Geckenli line and the capture of Kirk Kilisse (Kırklareli), the Ottoman forces retreated in disorder to the east and south. The Bulgarian Second Army under the command of gen. Nikola Ivanov besieged Adrianople (Edirne) but the First and Third armies failed to chase the retreating Ottoman forces. Thus the Ottomans were allowed to re-group and took new defensive positions along the Lule Burgas – Bunar Hisar line. The Bulgarian Third Army under gen. Radko Dimitriev reached the Ottoman lines on 28 October. The attack began the same day by the army's three divisions – 5th Danubian Infantry Division (commander major-gen. Pavel Hristov) on the left flank, 4th Preslav Infantry Division (major-gen. Kliment Boyadzhiev) in the centre and 6th Bdin Infantry Division (major-gen. Pravoslav Tenev) on the right flank. By the end of the day the 6th Division captured the town of Lule Burgas. With the arrival of the First Army on the battlefield the following day, attacks continued along the entire front line but were met with fierce resistance and even limited counter-attacks by the Ottomans. Heavy and bloody battles occurred on the next two days and the casualties were high on both sides. At the cost of heavy losses, the Bulgarian Fourth and 5th Division managed to push the Ottomans back and gained 5 km of land in their respective sectors of the frontline on 30 October.

The Bulgarians continued to push the Ottomans on the entire front. The 6th division managed to breach the Ottoman lines on the right flank. After another two days of fierce combat, the Ottoman defence collapsed and on the night of 2 November the Ottoman forces began a full retreat along the entire frontline. The Bulgarians again didn't immediately follow the retreating Ottoman forces and lost contact with them, which allowed the Ottoman army to take up positions on the Çatalca defence line just 30 km west of Constantinople.

There were a large number of journalists who reported on the Battle of Lule Burgas, whose accounts provide rich details about this event.

Battle of Merhamli

[edit]The Battle of Merhamli was part of the First Balkan War between the armies of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire which took place on 14/27 November 1912. After a long chase throughout Western Thrace the Bulgarian troops led by General Nikola Genev and Colonel Aleksandar Tanev surrounded the 10,000-strong Kırcaali Detachment under the command of Mehmed Yaver Pasha.[23] Attacked in the surrounding of the village Merhamli (Now Peplos in modern Greece), only a few of the Ottomans managed to cross the Maritsa River. The rest surrendered in the following day on 28 November. In the beginning of 1912 when the Ottoman-Montenegrin conflict from the previous month grew into Balkan-wide war the main forces of the adversaries were concentrated in Eastern Thrace and Macedonia. In the battle of Lule Burgas (28 October-2 November) the Ottoman Eastern Army was crushed by the Bulgarians and pushed to Constantinople and Gallipoli. On 9 November the Greeks captured Salonica.[24]

The actions in the Rhodope Mountains during the first month of the war were limited. After the Bulgarians captured Kardzhali (21 October) and Smolyan (26 October) the Bulgarian troops took defensive positions. The Ottoman attempts for counter-attacks against Kardzhali and Smolyan Battle of Alamidere failed and the front line stabilized along the Arda River.[25]

The main task of the Ottoman Kardzhali corps which was stationed in the Eastern Rhodopes was to prevent the Bulgarians from cutting the land communications between the Ottoman armies in Thrace and Macedonia. However, after the successes of the Balkan allies to the east and to the west, that task became pointless and after the Bulgarian High Command issued advance towards the important port of Dedeagach the situation of the corps became critical. Its commander Mehmed Yaver Pasha ordered a retreat to Galipoli with fighting in the rearguard.[26] After the fall of Salonica to the Balkan allies the Rodopi Detachment changed the direction of its advance. From Serres and Drama the detachment of General Stiliyan Kovachev headed eastwards and on 20 November captured Xanthi. Six days later his troops entered Dedeagach which was already taken by Macedonian volunteers.[27] In the Battle of Balkan Toresi on 20 November the Kardzhali Detachment (3rd Brigade of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps, two mixed regiment and other squads) defeated the Ottoman rearguard and entered Gyumyurdzhina in the next day. After several day march through the Eastern Rhodopes General Genev gave his troops a rest. On 25 November the detachment continued eastwards and after two days captured Feres in close proximity to the camp of Mehmed Yaver Pasha on the right banks of the Maritsa.[28] On 15 November the Mixed Cavalry Brigade of Colonel Tanev captured Soflu. Reinforced with the 2nd Brigade of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps he marched south along the Maritsa and on 18 November took Feres and on 19 November captured Dedeagach. However, concerned about the news for advancing Ottoman reinforcement, Tanev retreated back to Soflu leaving 150 volunteers in Dedeagach.[28]

On 26 November the corps of Mehmed Yaver Pasha reached Merhamli and began to cross the Maritsa but due to the torrential rains only 1,500-2,000 men with two guns managed to reach the left bank until noon in the next day. In the meantime the troops of Tanev attacked the Ottoman forces from the north and the detachment of Genev was closing in from the west. In the evening of 27 November Tanev forced the Ottoman commander to sign a document for capitulation.[29] The Ottomans surrendered in the next day after the Kardzhali Detachment arrived at Merhamli. Around 9,600 Ottoman soldiers and officers were captured along with 8 artillery guns.[30]

The survived Ottoman forces which managed to cross the Maritsa joined the Ottoman defenders in Galipoli.[26] With the capitulation at Merhamli the Ottoman Empire lost Western Thrace while the Bulgarian positions in the lower current of the Maritsa and around Istanbul stabilized. With their success the Mixed Cavalry Brigade and the Kardzhali Detachment secured the rear of the 2nd Army which was besieging Adrianople and eased the supplies for 1st and 3rd Armies at Chatalja.[31]

Battle of Kaliakra

[edit]The Battle of Kaliakra, usually known as the Attack of the Drazki (Bulgarian: Атаката на Дръзки) in Bulgaria, was a maritime action between four Bulgarian torpedo boats and the Ottoman cruiser Hamidiye in the Black Sea. It took place on 21 November 1912 at 32 miles off Bulgaria's primary port of Varna.

During the course of the First Balkan War, the Ottoman Empire's supplies were dangerously limited after the battles in Kirk Kilisse and Lule Burgas and the sea route from the Romanian port of Constanța to Istanbul became vital for the Ottomans. The Ottoman navy also imposed a blockade on the Bulgarian coast and on 15 October, the commander of the cruiser Hamidiye threatened to destroy Varna and Balchik, unless the two towns surrendered. On 21 November an Ottoman convoy was attacked by the four Bulgarian torpedo boats Drazki (Bold), Letyashti (Flying), Smeli (Brave) and Strogi (Strict). The attack was led by Letyashti, whose torpedoes missed, as did those of Smeli and Strogi, Smeli being damaged by a 150 mm round with one of her crewmen wounded. Drazki however got within 100 meters from the Ottoman cruiser and her torpedoes struck the cruiser's starboard side, causing a 10 square meter hole.

However, Hamidiye was not sunk, due to her well-trained crew, strong forward bulkheads, the functionality of all her water pumps and a very calm sea. She did however have 8 crewmen killed and 30 wounded, and was repaired within months. After this encounter, the Ottoman blockade of the Bulgarian coast was significantly loosened.

Battle of Çatalca

[edit]The First Battle of Çatalca was one of the heaviest battles of the First Balkan War fought between 17 and 18 November [O.S. 4–5 November] 1912. It was initiated as an attempt of the combined Bulgarian First and Third armies, under the overall command of lieutenant general Radko Dimitriev, to defeat the Ottoman Çatalca Army and break through the last Turkish defensive line before the capital Constantinople. The high casualties however forced the Bulgarians to call off the attack.[32]

Battle of Bulair

[edit]The battle of Bulair (Bulgarian: Битка при Булаир, Turkish: Bolayır Muharebesi) took place on 8 February 1913 (O.S. 26 January 1913) between the Bulgarian Seventh Rila Infantry Division under General Georgi Todorov and the Ottoman 27th Infantry Division. The result was a Bulgarian victory. The advance began in the morning of 8 February (O.S. 26 January) when the Myuretebi Division headed under the cover of fog from the Saor Bay toward the road to Bulair. The attack was uncovered at only 100 steps from the Bulgarian positions. At 7 o'clock the Ottoman artillery opened fire. The Bulgarian auxiliary artillery also opened fire, as did the soldiers of the 13th Infantry Regiment, and the enemy advance was slowed.

From 8 o'clock advanced the Ottoman 27th Infantry Division which concentrated on the shore-line of the Sea of Marmara. Due to their superiority the Ottomans seized the position at the Doganarslan Chiflik and began to surround the left wing of the 22nd Infantry Regiment. The command of the Seventh Rila Infantry Division reacted immediately and ordered a counter-attack of the 13th Rila Infantry Regiment, which forced the Myuretebi Division to pull back.

The Ottoman forces were surprised by the decisive actions of the Bulgarians and when they saw the advancing 22nd Thracian Infantry Regiment they panicked. The Bulgarian artillery now concentrated its fire on Doganarslan Chiflik. Around 15 o'clock 22nd Regiment counter-attacked the right wing of the Ottoman forces and after a short but fierce fight the enemy began to retreat. Many of the fleeing Ottoman troops were killed by the accurate fire of the Bulgarian artillery. After that the whole Bulgarian army attacked and defeated the Ottoman left wing.

Around 17 o'clock the Ottoman forces renewed the attack and headed towards the Bulgarian center but were repulsed and suffered heavy casualties.

The position was cleared of Ottoman forces and the defensive line was reorganized. In the battle of Bulair the Ottoman forces lost almost half of their manpower and left all their equipment on the battlefield.

Battle of Şarköy

[edit]The Battle of Şarköy or Sarkoy operation (Bulgarian: Битка при Шаркьой, Turkish: Şarköy Çıkarması) took place between 9 and 11 February 1913 during the First Balkan War between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans attempted a counter-attack, but were defeated by the Bulgarians at the Battles of Bulair and Şarköy.

Siege of Adrianople

[edit]The siege of Adrianople (Bulgarian: oбсада на Одрин, Serbian: oпсада Једрена, Turkish: Edirne kuşatması), was fought during the First Balkan War. The siege began on 3 November 1912 and ended on 26 March 1913 with the capture of Edirne (Adrianople) by the Bulgarian 2nd Army and the Serbian 2nd Army.

The loss of Edirne delivered the final decisive blow to the Ottoman army and brought the First Balkan War to an end. A treaty was signed in London on 30 May. The city was reoccupied and retained by the Ottomans during the Second Balkan War.

The victorious end of the siege was considered to be an enormous military success because the city's defenses had been carefully developed by leading German siege experts and called 'undefeatable'. The Bulgarian army, after five months of siege and two bold night attacks, took the Ottoman stronghold.

The victors were under the overall command of Bulgarian General Nikola Ivanov while the commander of the Bulgarian forces on the eastern sector of the fortress was General Georgi Vazov, the brother of the famous Bulgarian writer Ivan Vazov and of General Vladimir Vazov.

The early use of an airplane for bombing took place during the siege; the Bulgarians dropped special hand grenades from one or more airplanes in an effort to cause panic among the Ottoman soldiers. Many young Bulgarian officers and professionals who took part in this decisive battle would later play important roles in Bulgarian politics, culture, commerce and industry. The final battle consisted of two night attacks. Preparations for the battle included covering all metal parts of the uniforms and weapons with tissue to avoid any shine or noise. The armies that took part in the siege were put under joint command, creating a prototype of a front. Some light artillery pieces towed by horses followed the advancing units, which played the role of infantry support guns. Attempts were made to perturb all Ottoman radio communications to isolate and demoralize the besieged troops. On 24 March 1913, the external fortifications began to be captured and the next night, the fortress itself fell into Bulgarian hands. Early in the morning on 26 March 1913, the commander of the fortress, Mehmed Şükrü Pasha, surrendered to the Bulgarian Army, which ended the siege.

After the surrender, large parts of the city, especially the houses of Muslims and Jews, were subjected to looting for three days. The perpetrators of the looting, however, are disputed, in that some accounts accuse the Bulgarian army of looting while other sources accuse the local Greek population.

The Bulgarian achievements in the war were summarized by a British war correspondent as follows: "A nation with a population of less than five million and a military budget of less than two million pounds per annum placed in the field within fourteen days of mobilization an army of 400,000 men, and in the course of four weeks moved that army over 160 miles in hostile territory, captured one fortress and invested another, fought and won two great battles against the available armed strength of a nation of twenty million inhabitants, and stopped only at the gates of the hostile capital. With the exception of the Japanese and Gurkhas, the Bulgarians alone of all troops go into battle with the fixed intention of killing at least one enemy." There were many journalists who reported on the siege of Adrianople; their accounts provide rich details about the siege.

Serbian units involved were the 2nd Army, under the command of General (later Vojvoda, equivalent to Field Marshal) Stepa Stepanović (two divisions and some support units) and heavy artillery (38 siege cannons and howitzers of 120 and 150 mm purchased from French Schneider-Canet factory in 1908); they had been dispatched because the Bulgarians lacked heavy artillery (though they were well supplied with Krupp-designed 75 mm field artillery). Serbian forces, commanded by General Stepa Stepanović, arrived on 6 November 1912. In Mustafa Pasha Place, a railway station outside Odrin, Stepanović immediately reported to the supreme commander, General Nikola Ivanov. The Serbian Second Army was formed from the Timok Division without the 14th Regiment, the Second Danube Division reinforced with the 4th Reserve Regiment, and the Second Drina Artillery Division. There was a total of 47,275 Serbian troops with 72 artillery guns, 4,142 horses and oxen and 3,046 cars.

Both Serbian divisions were immediately sent to the front. The Timok Division, strengthened by a Bulgarian regiment, occupied the north-western sector between Maritsa and Tundzha Rivers, its sector being 15 km long. The Danube Division occupied a 5 km stretch of the western sector between the Maritsa and Arda Rivers. A combined brigade was formed from the Timok Cavalry Regiment and the Bulgarian guard Cavalry Regiment to scout the Maritsa Valley.

Second Battle of Çatalca

[edit]The Bulgarian advance at the beginning of the First Balkan War stalled at the Ottoman fortifications at Çatalca in November 1912 at the First Battle of Çatalca. A two-month ceasefire (armistice) was agreed to on 3 December [O.S. 20 November] 1912 to allow for peace talks to proceed in London. The talks there stalled when on 23 January [O.S. 10 January] 1913 an Ottoman coup d'état returned Unionists to power, with their non-negotiable stance on retaining Edirne.[33][34] Hostilities resumed upon expiration of the armistice, on 3 February [O.S. 21 January] 1913, and the Second Battle of Çatalca began.[33] The battle consisted of a series of thrusts and counter-thrusts by both the Ottomans and the Bulgarians.[35] On 20 February the Ottomans, in coordination with a separate attack from Gallipoli, charged the Bulgarian positions. Although the Bulgarians repulsed the initial attack, they were weakened enough that they withdrew over fifteen kilometers to the south and twenty kilometers to the west to secondary defensive positions; but eventually the lines returned to essentially the originals. The Bulgarians then moved a section of their army south threatening Çanakkale. The separate siege of Edirne resulted in its loss to the Bulgarians on 26 March, sapping Ottoman morale; and with heavy Bulgarian losses to both fighting and cholera, the battle dwindled down and ceased by 3 April 1913.[35] On 16 April a second ceasefire (armistice) was agreed to, ending the last fighting in the war.[33] The Ottomans held the "Çatalca Line", but failed to advance. The loss of Edirne ended the major Ottoman objection to peace and the Treaty of London on 10 June 1913 codified the Ottoman loss of territory.[33]

Aftermath

[edit]

The Treaty of London ended the First Balkan War on 30 May 1913. All Ottoman territory west of the Enez-Kıyıköy line was ceded to the Balkan League, according to the status quo at the time of the armistice. The treaty also declared Albania an independent state. Most of the territory designated to form the new Albanian state was occupied by Serbia and Greece, who only reluctantly withdrew their troops. Having unresolved disputes with Serbia over the division of northern Macedonia and with Greece over southern Macedonia, Bulgaria was prepared, if the need arose, to solve the problems by force, and began transferring its military from Eastern Thrace to the disputed regions. Unwilling to yield to any pressure, Greece and Serbia settled their mutual differences and signed a military alliance directed against Bulgaria on 1 May 1913, even before the Treaty of London had been concluded. This was soon followed by a treaty of "mutual friendship and protection" on 19 May/1 June 1913. This set the stage for the Second Balkan War.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Erickson (2003), s. 52

- ^ Bulgarian troops losses during the Balkan Wars

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 329

- ^ Noel Malcolm, A Short History of Kosovo, pp. 246–247

- ^ Olsi Jazexhi, Ottomans into Illyrians: passages to nationhood in 20th century Albania, pp. 86–89

- ^ Noel Malcolm, A Short History of Kosovo pp. 250–251.

- ^ The Ear Correspondence of Leon Trotsky: Hall, The Balkan Wars, 1912–13, 1980, p. 221

- ^ Joseph Vincent Fulle, Bismarck's Diplomacy at Its Zenith, 2005, p. 22

- ^ Dr. E.J. Dillon. "The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Inside Story of the Peace Conference". Mirrorservice.org. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Hugh Seton-Watson & Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe, 1981, p. 116

- ^ "Correspondants de guerre", Le Petit Journal Illustré (Paris), 3 Novembre 1912.

- ^ Day of Kardzhali – 21 October (retrieved on 5.01.2010)

- ^ a b Войната между България и Турция, Т. V, стр. 127

- ^ a b Иванов, Балканската война, стр. 43–44

- ^ Войната между България и Турция, Т. V, стр. 1072

- ^ a b Иванов, Балканската война, стр. 60

- ^ Войната между България и Турция, Т. V, стр. 151–152

- ^ Войната между България и Турция, Т. V, стр. 153–156

- ^ Войната между България и Турция, Т. V, стр. 157–163

- ^ Балканската война 1912–1913, София 1961, стр. 412

- ^ Edward J. Erickson, Defeat in detail: the Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913 , Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4, p. 86, 181.

- ^ Erickson (2003), p.102.

- ^ M. Türker Acaroğlu, Bulgaristan Türkleri Üzerine Araştırmalar, Cilt 1, Kültür Bakanlığı, 1999, p. 198. (in Turkish)

- ^ Марков, 1.3., 1.4.

- ^ Erickson, pp. 149-150

- ^ a b Erickson, стр. 151-153

- ^ БВ, стр. 298, 306

- ^ a b БВ, стр. 304-306

- ^ БВ, стр. 306-308

- ^ Марков, 2.2. (19.08.2009)

- ^ БВ, стр. 308

- ^ Vŭchkov, pp. 99-103

- ^ a b c d Zurcher, Erik Jan (2004). Turkey: A Modern History (3rd ed.). London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-1-86064-958-5.

- ^ Feroz Ahmad (2014). Turkey: The Quest for Identity (second ed.). London: Oneworld. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-78074-301-1.

- ^ a b Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 285 ff. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4.

Sources

[edit]- Балканската война 1912–1913. Държавно военно издателство, София 1961

- Войната между България и Турция, Том V: Операциите около Одринската крепост, Книга I, Министерство на войната, София 1930

- Иванов, Н. Балканската война 1912–1913 год. Действията на II армия. Обсада и атака на Одринската крепост. София 1924

- Министерство на войната, Щаб на войската (1928). Войната между България и Турция, vol. II. Държавна печатница, София.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-97888-5.

- Марков, Г. България в Балканския съюз срещу Османската империя 1912-1913 г., "Наука и изкуство", София 1989 (електронно издание „Книги за Македония“, 19.08.2009)

- Erickson, E. Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912-1913, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-275-97888-5

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- Vŭchkov, Aleksandŭr. (2005). The Balkan War 1912-1913. Angela. ISBN 954-90587-4-3.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97888-5.

- Fotakis, Zisis (2005). Greek Naval Strategy and Policy, 1910–1919. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35014-3.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- Hooton, Edward R. (2014). Prelude to the First World War: The Balkan Wars 1912–1913. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-180-6.

- Langensiepen, Bernd; Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy, 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press/Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-85177-610-8.

- Murray, Nicholas (2013). The Rocky Road to the Great War: the Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914. Dulles, Virginia, Potomac Books ISBN 978-1-59797-553-7

- Pettifer, James. War in the Balkans: Conflict and Diplomacy Before World War I (IB Tauris, 2015).

- Akmeşe, Handan Nezir (2015). The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to World I. I.B. Tauris.

- Schurman, Jacob Gould (2004). The Balkan Wars, 1912 to 1913. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger. ISBN 1-4191-5345-5.

- Seton-Watson, R. W. (2009) [1917]. The Rise of Nationality in the Balkans. Charleston, SC: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-113-88264-6.

- Trix, Frances. "Peace-mongering in 1913: the Carnegie International Commission of Inquiry and its Report on the Balkan Wars." First World War Studies 5.2 (2014): 147–162.

- Uyar, Mesut; Erickson, Edward (2009). A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Security International. ISBN 978-0-275-98876-0.

- Stojančević, Vladimir. Prvi balkanski rat: okrugli sto povodom 75. godišnjice 1912–1987, 28. i 29. oktobar 1987.

- Vŭchkov, Aleksandŭr (2005). The Balkan War 1912–1913. Angela. ISBN 978-954-90587-2-7.

- The Bulgarian Ministry of War (1928). Войната между България и Турция през 1912–1913 г. [The War between Bulgaria and Turkey, 1912–1913]. Vol. I, II, VI, VII. State Printing House.

Further reading

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27459-3.

External links

[edit]- Hall, Richard C.: Balkan Wars 1912–1913, in: 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Map of Europe during First Balkan War at omniatlas.com Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Films about the Balkan War at europeanfilmgateway.eu

- Clemmesen, M. H. Not Just a Prelude: The First Balkan War Crisis as the Catalyst of Final European War Preparations (2012)

- Anderson, D. S. The Apple of Discord: The Balkan League and the Military Topography of the First Balkan War (1993) Archived 20 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Major 1914 primary sources from BYU