732 Tjilaki

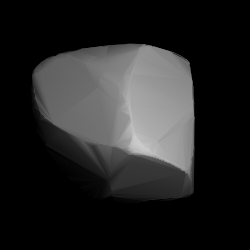

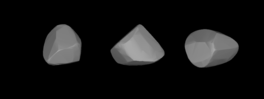

Modelled shape of Tjilaki from its lightcurve | |

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | A. Massinger |

| Discovery site | Heidelberg Obs. |

| Discovery date | 15 April 1912 |

| Designations | |

| (732) Tjilaki | |

| Pronunciation | Malay: [tʃiˈlaki] |

Named after | Cilaki River [2][3] (River in Indonesia) |

| A912 HK · 1958 FC 1912 OR | |

| Orbital characteristics [4] | |

| Epoch 31 May 2020 (JD 2459000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 106.66 yr (38,959 d) |

| Aphelion | 2.5633 AU |

| Perihelion | 2.3490 AU |

| 2.4561 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0436 |

| 3.85 yr (1,406 d) | |

| 359.80° | |

| 0° 15m 21.96s / day | |

| Inclination | 10.994° |

| 173.35° | |

| 64.900° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 12.34±0.01 h[11] | |

Pole ecliptic latitude | |

732 Tjilaki (prov. designation: A912 HK or 1912 OR) is a dark background asteroid, approximately 36 kilometers (22 miles) in diameter, located in the inner region of the asteroid belt. It was discovered by German astronomer Adam Massinger at the Heidelberg Observatory on 15 April 1912, and later named after the Cilaki (Tjilaki) river in Indonesia.[1][2] The dark D-type asteroid has a rotation period of 12.3 hours. It was an early candidate to be visited by the Rosetta spacecraft which eventually rendezvoused comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.[11]

Orbit and classification

[edit]Tjilaki is a non-family asteroid of the main belt's background population when applying the hierarchical clustering method to its proper orbital elements.[5][6][7] It orbits the Sun in the inner asteroid belt at a distance of 2.3–2.6 AU once every 3 years and 10 months (1,406 days; semi-major axis of 2.46 AU). Its orbit has an eccentricity of 0.04 and an inclination of 11° with respect to the ecliptic.[4] The body's observation arc begins at Heidelberg Observatory on 28 August 1913, or 16 months after its official discovery observation.[1]

Naming

[edit]This minor planet was named after the Cilaki (Tjilaki) river in West Java, Indonesia. The river rises in the mountains where the city of Malabar (see asteroid 754 Malabar) is located. The naming was mentioned in The Names of the Minor Planets by Paul Herget in 1955 (H 74).[2]

Rosetta mission

[edit]In the Phase A study of the Rosetta mission, Tjilaki was considered an alternative visiting target to comet 46P/Wirtanen.[11] However, both candidates were later abandoned in favor of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, which was visited by Rosetta in 2014. The retargeting was necessary as the spacecraft's launch window changed due to a delay caused by the launch failure of the Hot Bird 7 satellite on the maiden flight of the Ariane 5 ECA carrier rocket in 2002.

Physical characteristics

[edit]In both the Tholen- and SMASS-like taxonomic variants of the Small Solar System Objects Spectroscopic Survey (S3OS2), , Tjilaki is a dark D-type asteroid, uncommon in the inner but abundant in the outer asteroid belt as well as among the Jupiter trojan population.[6][12] Polarimetric observations also determined a D-type.[13][14]

Rotation period and poles

[edit]

In February 1996, a rotational lightcurve of Tjilaki was obtained from photometric observations over ten nights by European astronomers using the Dutch 0.9-metre Telescope and the Bochum 0.61-metre Telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile. Lightcurve analysis gave a rotation period of 12.34±0.01 hours with a brightness variation of 0.19±0.02 magnitude (U=3−).[11]

In May 2012, astronomers at the Palomar Transient Factory measured a period of 12.277±0.0048 hours (U=2).[14][15] Additional observations were made by the TESS-team in January 2019, and by amateur astronomers Axel Martin and Rui Goncalves in May 2020, reporting a concurring period of (12.3286±0.0005) and (12.3216±0.00144) hours with an amplitude of (0.16±0.03) and (0.287±0.004) magnitude, respectively (U=2/n.a.).[16][17]

In 2016, a modeled lightcurve gave a concurring sidereal period of 12.3411±0.0002 hours using data from the Uppsala Asteroid Photometric Catalogue, the Palomar Transient Factory survey, and individual observers, as well as sparse-in-time photometry from the NOFS, the Catalina Sky Survey, and the La Palma surveys (950). The study also determined two spin axes of (160.0°, 23.0°) and (353.0°, 24.0°) in ecliptic coordinates (λ, β).[18]

Diameter and albedo

[edit]According to the surveys carried out by the NEOWISE mission of NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), the Japanese Akari satellite, and the Infrared Astronomical Satellite IRAS, Tjilaki measures (29.791±0.431), (36.49±0.43) and (37.61±1.6) kilometers in diameter and its surface has an albedo of (0.138±0.024), (0.070±0.002) and (0.0655±0.006), respectively.[8][9][10] The Collaborative Asteroid Lightcurve Link derives an albedo of 0.0763 and a diameter of 37.69 kilometers based on an absolute magnitude of 10.53.[14]

Alternative mean-diameters published by the WISE team include (36.76±11.57 km) and (37.96±9.94 km) with a corresponding albedo of (0.09±0.06) and (0.15±0.05).[6][14] Two asteroid occultations on 20 June 2005 and on 28 July 2009, gave a best-fit ellipse dimension of (33.6 km × 33.6 km) and (37.7 km × 36.4 km), respectively, each with an intermediate quality rating of 2.[6] These timed observations are taken when the asteroid passes in front of a distant star.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "732 Tjilaki (A912 HK)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(732) Tjilaki". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 70. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_733. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ (in Indonesian) https://langitselatan.com/2011/01/12/nama-nama-indonesia-pun-tertera-di-angkasa/

- ^ a b c d "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 732 Tjilaki (A912 HK)" (2020-04-27 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Asteroid 732 Tjilaki – Proper Elements". AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Asteroid 732 Tjilaki". Small Bodies Data Ferret. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b Zappalà, V.; Bendjoya, Ph.; Cellino, A.; Farinella, P.; Froeschle, C. (1997). "Asteroid Dynamical Families". NASA Planetary Data System: EAR-A-5-DDR-FAMILY-V4.1. Retrieved 10 June 2020.} (PDS main page)

- ^ a b c d Mainzer, A. K.; Bauer, J. M.; Cutri, R. M.; Grav, T.; Kramer, E. A.; Masiero, J. R.; et al. (June 2016). "NEOWISE Diameters and Albedos V1.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Bibcode:2016PDSS..247.....M. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Usui, Fumihiko; Kuroda, Daisuke; Müller, Thomas G.; Hasegawa, Sunao; Ishiguro, Masateru; Ootsubo, Takafumi; et al. (October 2011). "Asteroid Catalog Using Akari: AKARI/IRC Mid-Infrared Asteroid Survey". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 63 (5): 1117–1138. Bibcode:2011PASJ...63.1117U. doi:10.1093/pasj/63.5.1117. (online, AcuA catalog p. 153)

- ^ a b c d Tedesco, E. F.; Noah, P. V.; Noah, M.; Price, S. D. (October 2004). "IRAS Minor Planet Survey V6.0". NASA Planetary Data System. 12: IRAS-A-FPA-3-RDR-IMPS-V6.0. Bibcode:2004PDSS...12.....T. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Florczak, M.; Dotto, E.; Barucci, M. A.; Birlan, M.; Erikson, A.; Fulchignoni, M.; et al. (November 1997). "Rotational properties of main belt asteroids: photoelectric and CCD observations of 15 objects". Planetary and Space Science. 45 (11): 1423–1435. Bibcode:1997P&SS...45.1423F. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(97)00121-9. ISSN 0032-0633.

- ^ a b Lazzaro, D.; Angeli, C. A.; Carvano, J. M.; Mothé-Diniz, T.; Duffard, R.; Florczak, M. (November 2004). "S3OS2: the visible spectroscopic survey of 820 asteroids" (PDF). Icarus. 172 (1): 179–220. Bibcode:2004Icar..172..179L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.06.006. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ a b Belskaya, I. N.; Fornasier, S.; Tozzi, G. P.; Gil-Hutton, R.; Cellino, A.; Antonyuk, K.; et al. (March 2017). "Refining the asteroid taxonomy by polarimetric observations". Icarus. 284: 30–42. Bibcode:2017Icar..284...30B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.11.003. hdl:11336/63617. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ a b c d "LCDB Data for (732) Tjilaki". Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Waszczak, Adam; Chang, Chan-Kao; Ofek, Eran O.; Laher, Russ; Masci, Frank; Levitan, David; et al. (September 2015). "Asteroid Light Curves from the Palomar Transient Factory Survey: Rotation Periods and Phase Functions from Sparse Photometry". The Astronomical Journal. 150 (3): 35. arXiv:1504.04041. Bibcode:2015AJ....150...75W. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/3/75. S2CID 8342929.

- ^ Pál, András; Szakáts, Róbert; Kiss, Csaba; Bódi, Attila; Bognár, Zsófia; Kalup, Csilla; et al. (March 2020). "Solar System Objects Observed with TESS—First Data Release: Bright Main-belt and Trojan Asteroids from the Southern Survey". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 247 (1): 26. arXiv:2001.05822. Bibcode:2020ApJS..247...26P. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ab64f0. ISSN 0067-0049.

- ^ Behrend, Raoul. "Asteroids and comets rotation curves – (732) Tjilaki". Geneva Observatory. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Hanuš, J.; Ďurech, J.; Brož, M.; Marciniak, A.; Warner, B. D.; Pilcher, F.; et al. (March 2013). "Asteroids' physical models from combined dense and sparse photometry and scaling of the YORP effect by the observed obliquity distribution". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 551: A67. arXiv:1301.6943. Bibcode:2013A&A...551A..67H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220701. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 118627434.

External links

[edit]- Lightcurve Database Query (LCDB), at www.minorplanet.info

- Dictionary of Minor Planet Names, Google books

- Asteroids and comets rotation curves, CdR – Geneva Observatory, Raoul Behrend

- Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (1)-(5000) – Minor Planet Center

- 732 Tjilaki at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 732 Tjilaki at the JPL Small-Body Database