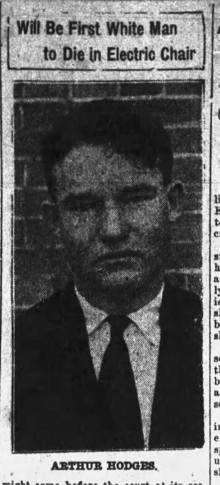

Arthur Hodges

Arthur Hodges | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1893 |

| Died | December 18, 1914 (age 21) |

| Cause of death | Execution by electrocution |

| Resting place | Arkansas Prison Cemetery |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Criminal charge | First degree murder |

| Penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | William Morgan Garner |

| Date | July 3, 1913 |

Arthur Hodges (c. 1893 – December 18, 1914) was a white man who became the first person in Clark County, Arkansas to be executed by means of the electric chair. Prior to that all executions were carried out by way of hanging or firing squad. He was convicted of the murder of Clark County Constable William Morgan Garner.

Hodges was the fourth person executed by electrocution in Arkansas, the first white person executed in the electric chair in Arkansas, and one of eight men scheduled to be executed by the state in a 16-day period, although only two of those executions were ever carried out.

Background

[edit]Arthur Hodges was originally from Okolona, Arkansas. Newspapers described Hodges as having a "mind of a child" and being intellectually disabled to the point of reporters speculating on the morning of his execution if he was aware he was going to die.[1][2] At the time of the murder for which Hodges was executed, Hodges was visiting relatives near Amity, Arkansas, a city in Clark County.[3]

Murder

[edit]The 21-year-old Hodges was convicted of killing Clark County constable William Morgan Garner while resisting arrest. The shooting took place on July 3, 1913, and Garner died the next day, on July 4.[3]

As described in court documents, Constable Garner, assisted by citizen J.E. Chancellor, arrested Hodges for the theft of a pistol and some small items of value. Hodges inquired as to whether Garner had a warrant for his arrest, to which Garner replied he did not. Hodges then refused to be arrested, at which point Garner produced his service pistol, ordering Hodges to put his hands up and submit to a search. Hodges did have a pistol on his person, but Garner, by Hodges' own admission, failed to find the weapon during a search of him.[4]

Hodges claimed that he was abused physically by Garner, and that while en route to the jail Garner threatened to shoot him. Hodges then claimed that he produced his own pistol, which Garner had not located, and fired in an effort to frighten Garner. Instead, Garner was shot twice, killing him.[4]

Trial and appeals

[edit]Hodges was convicted of Garner's murder on September 20, 1913, and sentenced to death; his first execution date was set for November 12. He did not have the money to appeal his death sentence. However, third parties learned about his case and raised money for him to pursue an appeal, leading to him receiving a stay of execution on November 10, two days before his scheduled death.[1] However, the Clark County decision was upheld.[4][5]

After Hodges' death sentence was upheld, on October 12, 1914, Governor George Washington Hays set a new execution date of November 14, 1914. Hodges then petitioned for an inquiry to be made to investigate whether he was criminally insane at the time of Garner's murder. When this failed, Governor Hays rescheduled the execution for November 21, which was later pushed back to the final date of December 18.[1]

Execution

[edit]Arthur Hodges was executed on December 18, 1914. His execution made him the first white person to be executed in the electric chair in the state and only one of 57 total (constituting 29 percent of the executions in Arkansas' electric chair).[6] Hodges spent his last hours praying with a group of religious advisors, singing hymns, and being baptized; he also arranged for some of his affects to be sent to a sister who lived in Texas. Religious advisors who attended to Hodges in his last moments stated that Hodges remained hopeful until the last moment for a delay in his execution; when the Arkansas Supreme Court declared their refusal to intervene and permitted Hodges' execution to move forward, Hodges remarked to a reporter from the Arkansas Gazette, "I won't have any girl now, will I?"[1][2]

The execution was witnessed by approximately 12 individuals, including several physicians and a newspaper reporter. Hodges entered the death chamber at 9:36 am, and a physician pronounced him dead three minutes later at 9:39. Many newspapers were bereft of details on Hodges' execution because of a law in Arkansas forbidding the press from publishing specific details of executions in the electric chair.[1][7] At the time of Hodges' execution, the electric chair in Arkansas was housed at the Arkansas State Penitentiary in Little Rock, Arkansas. After his execution, Hodges' body was laid to rest in that prison's cemetery.[1]

Hodges's execution was scheduled to be one of eight to take place in a 16-day span in Arkansas' electric chair. Four of those executions were to be of black inmates, while four were to be of white inmates, including Hodges and also including Neal McLaughlin, a convicted rapist with an execution date of December 2, and Joe Strong and Clarence Dewein, two young white men "scarcely more than of age" who murdered a storekeeper. The black inmates scheduled to die were Gillespie Glover, convicted of uxoricide and scheduled to die on December 4; Will McNeeley (aka Will Neeley), convicted of murdering a deputy sheriff in Union County and scheduled to die on December 8; Lemuel Stephens, convicted of uxoricide and scheduled to die on December 17; and Rice King, scheduled to die on December 16 for murdering a black woman. However, only two of those executions ever actually took place: that of Hodges on December 18, and that of McNeeley/Neeley ten days prior, on December 8, 1914.[8][9]

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Arthur Hodges Goes to His Death Showing No Emotion". Daily Arkansas Gazette. 1914-12-19. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Arthur Hodges to Die This Morning (pt. 1)". Daily Arkansas Gazette. 1914-12-18. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Amity Officer Slain Thursday". The Southern Standard. 1913-07-10. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "HODGES v. STATE". VLex. 1914-01-12. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ "Ferguson v. Martineau". vLex. 1914-11-20. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ "A century of death: 196 executions, 15 governors, and Arkansas' deadliest day". KATV. 2017-04-02. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ "Arthur Hodges Dies in Chair". Log Cabin Democrat. 1914-12-18. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Espy Files" (PDF). Death Penalty Information Center. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-05. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ "Eight to Die in Arkansas". The Taloga Advocate. 1914-11-28. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2024-05-29. Retrieved 2024-05-29 – via Newspapers.com.