Wikipedia:WikiProject Military history/News/March 2015/Op-ed

|

Blind Man's Bluff |

- By TomStar81

In February 1915, the German government gave the green light to the Imperial German Navy to commence unrestricted submarine warfare. This decision, which came nearly nine months after the outbreak of the war, arrived at time when the nations of Europe had begun to reach an unfortunate but inescapable truth: this war would not be over quickly. With this realization came the terrible burden of deciding how best to advance the course of the war so that it could be brought to end in favor of one of the two alliances fighting. With the introduction of chemical warfare agents on the western front by the Imperial German Army, the decision was made to loose the submarines on Allied shipping with a declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare.

At the time the decision was issued and the orders for the campaign handed down, it was widely believed by those in the British Empire that the home island would starve for lack of supplies in the event that the Germans resorted to unrestricted submarine warfare, and it was equally held belief that the United States would be the only nation able to keep the British Empire's home island up and running in the event of the outbreak of unrestricted warfare. The enormity of the matter of unrestricted submarine warfare was not lost on the Germans either, the fear of inadvertently creating a diplomatic crisis with the United States or other armed and at the time neutral parties had kept German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg from issuing any such order for unrestricted submarine warfare until early 1915, when Imperial German Navy Admiral Hugo von Pohl - an outspoken supporter of unrestricted submarine warfare - issued a declaration in the German Gazette notifying the public that:

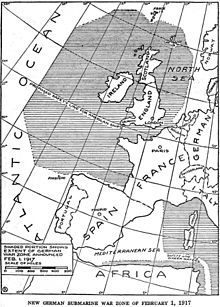

(1) The waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a War Zone. From February 18 onwards every enemy merchant vessel encountered in this zone will be destroyed, nor will it always be possible to avert the danger thereby threatened to the crew and passengers.

(2) Neutral vessels also will run a risk in the War Zone, because in view of the hazards of sea warfare and the British authorization of January 31 of the misuse of neutral flags, it may not always be possible to prevent attacks on enemy ships from harming neutral ships.

As the Imperial German Navy submarines were loosed on the ships in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea allied forces discovered much to their displeasure that the submarines were virtually impossible to detect and counter. No proper antisubmarine warfare tactics and strategies had been developed since the submarine had up till that time been a non-factor in naval matters. Now, suddenly, military and merchant shipping was under attack from an enemy that could not be detected save but for the identification of the periscope. In a time before the introduction of depth charges and guided torpedos, the best tactic that the Royal Navy and other allied navies had come up with to counter the threat of German U-boat attacks was to simply ram the enemy submarine to disable the periscope. This, however, was a poor solution to an urgent and disconcerting problem, and as a direct result of the need to better defend allied ships and allied shipping scientists and other government agencies began working on sonar units for their ships to detect enemy submarines. In time, this would help to develop the anti-submarine technology that would be used in the Second World War against German U-Boats.

In the weeks after the decision to engage in unrestricted submarine warfare the Imperial German Navy had great success in intercepting and destroying enemy naval units and merchant shipping, however in May of 1915 the disaster that Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg foresaw would occur when RMS Lusitania was torpedoed with a large loss of life. Efforts to explain and/or justify the decision to attack the passenger liner met with outrage and deaf ears in the international community, and much more ominously, would result in a shifting of mental positions among the citizens of the United States, who would gradually come to view intervention on the side of the Allied Powers as a real and plausible course of action.

|