The Serbian Radical Party (Serbian: Српска радикална странка, romanized: Srpska radikalna stranka, abbr. SRS) is a far-right,[1] ultranationalist[2] political party in Serbia. Founded in 1991, its co-founder, first and only leader is Vojislav Šešelj.[3]

Serbian Radical Party Српска радикална странка | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | SRS |

| President | Vojislav Šešelj |

| Deputy President | Aleksandar Šešelj |

| Vice-Presidents | |

| Founders |

|

| Founded | 23 February 1991 |

| Split from | |

| Headquarters | Magistratski trg 3, Belgrade |

| Newspaper | Velika Srbija |

| Paramilitary wing | White Eagles (1991–1995) |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Colours | Blue |

| Slogan | "Србија је вечна док су јој деца верна" ("Serbia is eternal as long as its children are loyal") |

| Anthem | "Sprem'te se sprem'te" |

| National Assembly | 0 / 250 |

| Assembly of Vojvodina | 0 / 120 |

| City Assembly of Belgrade | 2 / 110 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| srpskaradikalnastranka | |

The SRS was founded in 1991 as a merger of the Serbian Chetnik Movement, led by Šešelj, and the People's Radical Party, led by Tomislav Nikolić. Upon formation, they became the president and deputy president of SRS respectively. During the first half of the 1990s the SRS supported the ruling Socialist Party of Serbia regime, which had contributed greatly to the rise of SRS through the use of media.[3] The party had strong support until the 2000 election, when SRS suffered a major defeat, but through populist rhetoric it became the most voted party in the early-to-mid 2000s. Šešelj voluntarily surrendered to the ICTY to defend himself against charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity that he was alleged to have committed during the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War. Nikolić assumed de facto party leadership until he left the party in 2008.[4]

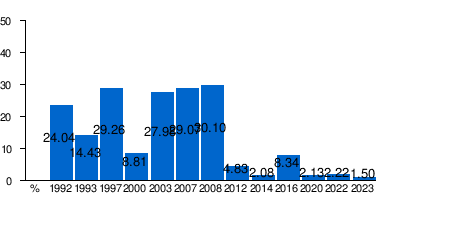

During the years of Nikolić's leadership, SRS blended ultranationalism with brash, populist, and anti-corruption rhetoric.[5] Due to disagreements with Šešelj over European Union integration, Nikolić took many of the high-ranking members of the party to form the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), which became the ruling party of Serbia in 2012. After the split, Dragan Todorović assumed de facto leadership, and the party went into a major decline, only pulling 4% of the vote in 2012 and 2% in 2014, the first time that SRS was not represented in the parliament. Shortly after Šešelj's return to Serbia in 2014, the party gained back some of its popularity and it placed third with 8% of the vote in the 2016 election.[6] In late 2019, the party went into decline again, and in the 2020 election it ended up only with 2% of the vote and gaining no seats in the parliament again.

A right-wing populist party,[7][8][9] SRS supports the creation of a Greater Serbia.[10][11] It is Eurosceptic, anti-Western orientated, opposed to the accession of Serbia to the European Union and supports establishing closer ties with Russia instead.[12][13][14] Some journalists described SRS as neofascist in the 1990s due to its vocal support of ultranationalism.[15][16][17][18] Regarding social issues, SRS is traditionalist.[19] It also holds local branches in some of the neighbouring states.

Ideology

editThe party's core ideology is based on Serbian nationalism and the goal of creating a Greater Serbia.[10][11] The party is also strongly opposed to European integration (euroscepticism[13]) and globalisation,[20][21][22] advocating closer ties with Russia instead.[20][22] The SRS is extremely critical of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), where Šešelj was incarcerated from 2003 to 2014.[23] The party regards former general Ratko Mladić and former Republika Srpska president Radovan Karadžić as "Serbian heroes".[24][25]

In 2007, the party advocated the use of military force to prevent the independence of Kosovo.[20]

Due to Tomislav Nikolić's support for the accession of Serbia to the European Union conflicting with the party's original hardline policy, Nikolić was expelled in 2008. With his supporters breaking apart from the SRS, he founded the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS)[4] which succeeded the SRS as one of the country's leading parties.

In the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, SRS was briefly associated with the Free Democrats Group in 2019.[26]

History

editFoundation

editThe Serbian Radical Party (SRS) was formed on 23 February 1991 by the merger of Vojislav Šešelj's Serbian Chetnik Movement (SČP) and the National Radical Party (NRS).[27] The SČP had been formed in 1990, although it was denied official registration due to its overt identification with the historical Chetniks. Formation of the new party followed Šešelj's breakaway from the Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO) due to internal quarrels with Vuk Drašković; the SPO having been founded by the merger of Šešelj's former Serbian Freedom Movement and Drašković's faction from the Serbian National Renewal.[27] Šešelj was chosen as the first president of the SRS while Tomislav Nikolić, a member of the NRS, became deputy president.[27]

Rise under SPS

editLed by Milošević, the Socialist Party (SPS) contributed greatly to the rise of the SRS through its use of the media.[3] With the SRS allowed to promulgate its ultranationalist views on state television, the SPS could present itself as a comparatively moderate, yet still patriotic party.[28] Šešelj promoted popular notions of an "international conspiracy against the Serbs," the foremost of which involved Germany, the Vatican, the CIA, Italy, Turkey, as well as the centrist Serbian political parties. Such conspiracy theories were also promoted by Milošević-controlled media.[29] In 1991, Šešelj became a Member of Parliament as an independent candidate,[30] and created a belligerent image by engaging in physical fights with opponents of the government.[29]

The 22.6% of the vote won by the SRS in the 1992 parliamentary election confirmed the party's rapid rise and made it the second largest parliamentary party.[31] Šešelj campaigned for the election on issues such as driving Albanians out of Kosovo to Albania, expelling Muslims from Sandžak, and forcing the Croats out of Vojvodina.[32] Having helped engineer the party's election to parliament,[28] the SPS formed an informal coalition with the SRS,[33] and collaborated on ousting moderate politicians from public office.[28][34][35]

Milošević breaks with SRS

editBy late 1993 the parties had turned against each other.[28][34][36] Milošević saw it necessary to change his policies and distance himself from the SRS in order for his new peacemaking orientation to be taken seriously by the West, as well as to counter the effects of United Nations sanctions against the country.[36] Many socialists also feared competition from the party based on its strong growth record.[36] As discord erupted among the opposition including the SRS, Milošević called new elections in 1993. These cut SRS support almost in half, while the SPS increased its share of the vote from 28% to 38%.[37] Although most people had grown tired of the wars, UN sanctions and the catastrophic economic situation, the SRS had also been subjected to powerful state propaganda and exclusion by the media.[38] Following Milošević's agreement to the Dayton accords in 1995 to bring peace to Bosnia, Šešelj denounced Milošević as "the worst traitor in Serbian history", and likened the event to Serbia's greatest defeat since the Battle of Kosovo fought against the Ottoman Empire in 1389.[34]

In 1995, Šešelj and the SRS joined in a technical coalition with the centrist Democratic Party (DS) and the conservative Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS).[39] This gave Šešelj a degree of democratic legitimacy, although the coalition withered away by the end of the same year.[39]

Kosovo war and Milošević's overthrow

editWhen Šešelj beat the SPS candidate for the 1997 presidential election, despite the contest being declared invalid due to low turnout, he was again brought into the Serbian government.[34] In 1998 the SRS and SPO entered the so-called "war" government, and as Deputy Prime Minister, Šešelj passed new information laws and helped launch propaganda offensives against Kosovo Albanians.[40] U.S. officials in turn branded him a "fascist", while the U.S. Department of State declared that they would never deal with him.[34] Following the 1999 NATO occupation of Kosovo, Šešelj resigned from government until his party was enticed to re-enter the administration by the SPS.[40] As the party had held posts under Milošević's regime, it was excluded from the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS), and suffered a major defeat in the 2000 parliamentary election when Milošević was ousted.[40][41]

Indictment of Šešelj

editDuring the Yugoslav Wars some SRS supporters including Šešelj were active in paramilitary units loyal to the federal government, serving as his "iron fist" during military campaigns.[20][42] Milošević's regime at times supported Šešelj and provided him with arms, whilst at others it accused him of war crimes.[43] The SRS was also provided with resources to establish paramilitary volunteer forces such as the White Eagles.[28] As the SRS protested against Milošević's extradition to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 2001, Milošević urged his supporters to vote for the SRS rather than his own SPS.[20] The ICTY also indicted Šešelj, who has been on trial since 2007 following his surrender in 2003.[44] Deputy President Nikolić became the new de facto SRS leader and presented a more moderate face, with a new approach to international cooperation and a vision of Serbia acting as a "link between the West and the East."[45]

Nikolić leadership

editDuring the 2003 parliamentary election, the SRS condemned cooperation with the war crimes tribunal, corruption scandals in government, poor living standards, and slightly moderated its formerly aggressive rhetoric.[41] While it won a clear plurality with 28% of the vote and 82 seats, the party was still viewed as a pariah by its democratic rivals and was thus left in opposition.[41] In the 2007 parliamentary election it won 29% of the vote and 81 seats. The SRS caucus in parliament elected Nikolić as its president and Aleksandar Vučić vice-president. Nikolić was later chosen as parliamentary speaker, supported by the DSS amidst a deadlock in coalition talks.[46] He stepped down just five days later, as the DS and DSS agreed to form a coalition government.[47]

At the National Assembly's first session on 14 February 2007, politicians voted overwhelmingly to reject the proposal by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari on the preliminary resolution of the status of Kosovo.[48] New elections were called in 2008 as the DS-DSS coalition collapsed due to EU recognition of Kosovo's declaration of independence.[49][50] In the 2008 parliamentary election the SRS again won 29% of the vote, and 78 seats, leading to the formation of a DS-SPS-led government coalition.[51][52] The party also won 17 seats in the Kosovska Mitrovica-based Community Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija consisting of Kosovan Serb municipalities who defied Kosovo's declaration of independence.[53]

2008 split

editAfter disagreements with Šešelj, on 8 September 2008, Nikolić formed the new parliamentary group Napred Srbijo! ("Forward Serbia!") along with a number of other SRS members.[21] Šešelj responded with a letter on 11 September addressed to SRS members, in which he condemned the Nikolić group as "traitors" and "Western puppets", while calling on SRS members to remain loyal to the ideologies of "Serbian nationalism, anti-globalism, and Russophilia."[21] Nikolić and his group were officially expelled from the SRS the next day,[21][54] in response to which Nikolić announced that he would form his own party.[55] On 14 September, SRS general secretary Aleksandar Vučić also resigned from the SRS.[21][56] Nikolić and Vučić then launched the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) on 21 October of the same year.[57][58]

Following their departure, Dragan Todorović took over as the party's acting leader from Nikolić;[59][60] however the office of deputy chairman was officially abolished.[61] By April 2011 the SRS had about 7% of support in opinion polls, while the SNS and its coalition partners held about 40%.[62][63] In the 2012 parliamentary election the Radical Party received only 4.63% of the popular vote, thus failing to cross the 5% threshold to enter parliament for the first time in the party's history.[64]

Šešelj's return

editThis article needs to be updated. (January 2017) |

With their leader back in Serbia in 2014, the party campaigned for the parliamentary election of 2016 aiming to restore its presence prior to 2008. They received 8.34% of the popular vote and gained back 22 seats. In the 2020 parliamentary election, the SRS received 2.22% of the votes, thus failing to get above the new 3% threshold and lost all their seats.[65] In the following elections, they did not receive enough votes to cross the electoral threshold.[66]

The party formed an alliance with the ruling Serbian Progressive Party to contest the 2023 Belgrade City Assembly election.[67] This announcement caused attention in national media.[68][69][70] In the 2024 Belgrade City Assembly election, the party gained 2 seats whilst being with the ruling SNS coalition.[71][72] During the 2024 local election, the SRS cooperated with the SNS coalition.

International relations

editThe Serbian Radical Party maintains ties with the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia and had ties with the French National Front party in the 1990s.[20][39][73] The SRS also has minimal ties with the far-right Golden Dawn party in Greece, focusing on religious similarities, and the Forza Nuova party in Italy.[74]

The party counted Iraq's Saddam Hussein and the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party as one of its political and financial backers until the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as the parties found common cause in defiance of the United States.[20] Similar sentiment led the party to back Libya's Muammar Gaddafi following the 2011 military intervention in Libya by NATO. Serbia and Libya had maintained good relations since Gaddafi vocally opposed NATO intervention in Serbia in the 1990s, while he also backed Serbia's opposition to Kosovo's independence.[75] The SRS has also expressed support for Syrian president Bashar al-Assad following the Syrian Civil War.[76] Šešelj advocates for a neutral position on the Israel-Palestine conflict, balancing Serbia's strong relations with both countries.[77]

On 9 March 2016 Šešelj and Zmago Jelinčič, president of the Slovenian National Party, signed an agreement with the intention of bringing their parties closer in terms of partnership and political alliance.[78]

List of presidents

edit| # | President | Birth–Death | Term start | Term end | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vojislav Šešelj[nb 1] | 1954– | 23 February 1991 | Incumbent | ||

Acting leaders during the incarceration of Šešelj

editŠešelj was incarcerated at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) from 2003 to 2014.[79]

| # | Name | Birth–Death | Term start | Term end | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tomislav Nikolić[nb 2] | 1952– | 24 February 2003 | 5 September 2008 | ||

| 2 | Dragan Todorović[nb 3] | 1953– | 5 September 2008 | 26 May 2012 | ||

| 3 | Nemanja Šarović[nb 2] | 1974– | 26 May 2012 | 12 November 2014 | ||

Electoral results

editParliamentary elections

edit| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Vojislav Šešelj | 1,066,765 | 24.04% | 2nd | 73 / 250

|

New | Support |

| 1993 | 595,467 | 14.43% | 3rd | 39 / 250

|

34 | Opposition | |

| 1997 | 1,162,216 | 29.26% | 2nd | 82 / 250

|

43 | Government | |

| 2000 | 322,333 | 8.81% | 3rd | 23 / 250

|

59 | Opposition | |

| 2003 | 1,069,212 | 27.98% | 1st | 82 / 250

|

59 | Opposition | |

| 2007 | 1,153,453 | 29.07% | 1st | 81 / 250

|

1 | Opposition | |

| 2008 | 1,219,436 | 30.10% | 2nd | 78 / 250

|

3 | Opposition | |

| 2012 | 180,558 | 4.83% | 7th | 0 / 250

|

78 | Extra-parliamentary | |

| 2014 | 72,303 | 2.08% | 11th | 0 / 250

|

0 | Extra-parliamentary | |

| 2016 | 306,052 | 8.34% | 3rd | 22 / 250

|

22 | Opposition | |

| 2020 | 65,954 | 2.13% | 8th | 0 / 250

|

22 | Extra-parliamentary | |

| 2022 | 82,066 | 2.22% | 9th | 0 / 250

|

0 | Extra-parliamentary | |

| 2023 | 55,782 | 1.50% | 8th | 0 / 250

|

0 | Extra-parliamentary |

Years in government (1991– )

edit

Presidential elections

edit| Election year | Candidate | 1st Round | 2nd Round | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Votes | % Votes | # Votes | % Votes | |||

| 1990[a] | Vojislav Šešelj | 96,277 | 1.98% | — | Lost | |

| 1992[b] | Slobodan Milošević | 2,515,047 | 57.46% | — | Won | |

| Sep 1997[c] | Vojislav Šešelj | 1,126,940 | 28.36% | 1,733,859 | 50.62% | Won |

| Dec 1997 | 1,227,076 | 32.87% | 1,383,868 | 38.81% | Lost | |

| Sep 2002[c] | 845,308 | 23.74% | — | Lost | ||

| Dec 2002[c] | 1,063,296 | 37.10% | — | Lost | ||

| 2003[c] | Tomislav Nikolić | 1,166,896 | 47.87% | — | Won | |

| 2004 | 954,339 | 30.97% | 1,434,068 | 46.03% | Lost | |

| 2008 | 1,646,172 | 40.76% | 2,197,155 | 48.81% | Lost | |

| 2012 | Jadranka Šešelj | 147,793 | 3.96% | — | Lost | |

| 2017 | Vojislav Šešelj | 163,802 | 4.56% | — | Lost | |

| 2022[d] | Aleksandar Vučić | 2,224,914 | 60.01% | — | Won | |

Positions held

editMajor positions held by Serbian Radical Party members:

| President of the National Assembly of Serbia | Years |

|---|---|

| Tomislav Nikolić | 2007

|

| Mayor of Novi Sad | Years |

| Milorad Mirčić | 1993–1994 |

| Maja Gojković | 2004–2008 |

See also

editReferences

edit- Notes

- Footnotes

- ^

- Reinhard Heinisch; Emanuele Massetti; Oscar Mazzoleni, eds. (2019). The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9781351265546.

The program of the radical right-wing SRS was founded upon the same principles.

- Kolstø, Pål (2009). Media Discourse and the Yugoslav Conflicts : Representations of Self and Other. Ashgate. p. 106. ISBN 978-0754676294.

- Collective (2005). Serbia since 1989: politics and society under Milošević and after. University of Washington Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-0295986500.

- Michael Minkenberg (15 April 2014). Historical Legacies and the Radical Right in Post-Cold War Central and Eastern Europe. Columbia University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-3-8382-6124-9.

- Džuverović, Nemanja; Stojarová, Věra (2022). Peace and Security in the Western Balkans: A Local Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000628722.

Although far-right parties are numerous throughout the region, they can boast no real successes, with the exception the far-right Serbian Radical Party (Srpska Radikalna Stranka, SRS)

- Sōtēropulos, Dēmētrēs A. (2023). The irregular pendulum of democracy: populism, clientelism and corruption in post-Yugoslav successor states. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 146. ISBN 9783031256097.

- Levitsky, Steven; Way, Lucan A. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9781139491488.

- Reinhard Heinisch; Emanuele Massetti; Oscar Mazzoleni, eds. (2019). The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9781351265546.

- ^

- "Serbs 'desperate for change'". Al Jazeera. 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Dragojević, Mila (2014). The Politics of Social Ties: Immigrants in an Ethnic Homeland. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 90. ISBN 9781472426949.

- Ford, Peter (2018). "Serbian Radical Party surge may complicate reform". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Evil tweet by Serbia's official on Srebrenica woman death". N1. 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Traynor, Ian (8 May 2007). "Extreme nationalist elected speaker of Serbian parliament". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- "Ultranationalists top Serb poll". BBC News. 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- "Party claims ultranationalist leader trampled Croatian flag". N1. 2018. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Grand, Stephen R. (2014). Understanding Tahrir Square: What Transitions Elsewhere Can Teach Us about the Prospects for Arab Democracy. 2014: Brookings Institution Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780815725176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ a b c Pribićević 1999, p. 193.

- ^ a b "Serb opposition leader resigns". BBC News. 7 September 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Ostojić, Mladen (2016). Between Justice and Stability: The Politics of War Crimes Prosecutions in Post-Miloševic Serbia. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9781317175001.

- ^ Delauney, Guy (25 April 2016). "Serbia elections: Radical Seselj back in parliament". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Wodak, Ruth; Mral, Brigitte (2013). Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. A&C Black. p. 19.

- ^ "Populism in the Balkans. The Case of Serbia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Mootz, Lisa (2010). Nations in Transit 2010: Democratization from Central Europe to Eurasia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 457. ISBN 9780932088727.

- ^ a b Mardell, Mark (26 January 2007). "Europe diary: Serbian Radicals". BBC News. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Seselj, Greater Serbia and Hoolbroke's shoes". SENSE Tribunal. 19 August 2005. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "СРС: Србија да буде у ОДКБ - војном савезу који предводи Русија". РТВ. Танјуг. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ a b "The changing nature of Serbian political parties' attitudes towards Serbian EU membership". Sussex European Institute. August 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Stojić, Marko (2017). Party Responses to the EU in the Western Balkans: Transformation, Opposition or Defiance?. Springer. p. 92. ISBN 9783319595634.

- ^ Ottaway, David (22 October 1993). "PRESIDENT OF SERBIA DISSOLVES PARLIAMENT". Washington Post. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (2004). "Hardliner looks set to win poll in Serbia". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Zimonjic, Vesna (1997). "YUGOSLAVIA: Fascism Knocking On Serbia's Door". INTER PRESS SERVICE News Agency. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Bodi, Faisal (2002). "Call this monster by its name". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Mila Dragojević (2016) [2014]. The Politics of Social Ties: Immigrants in an Ethnic Homeland, Routledge, p. 90

- ^ a b c d e f g Stojanovic, Dusan (24 January 2007). "Serbian Radical Party Riding High". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Rossi, Michael (October 2009). Resurrecting The Past: Democracy, National Identity and Historical Memory in Modern Serbia (PhD thesis). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University. p. 12.

- ^ a b Traynor, Ian (8 May 2007). "Extreme nationalist elected speaker of Serbian parliament". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Galanova, Mira (8 May 2008). "Serbia: rising nationalism imperils Mladic, Karadzic hunt". cafebabel.com. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Karadzic arrest: Reaction in quotes". BBC News. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Court finds Ratko Mladic fit for extradition". Al Jazeera. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Mr Aleksandar ŠEŠELJ (Serbia, NR)". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The three Yugoslavias: state-building and legitimation, 1918–2005. Indiana University. pp. 358–359. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Bugajski 2002, p. 416.

- ^ a b Pribićević 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Bugajski 2002, p. 415.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, p. 201.

- ^ Bugajski 2002, p. 415–416.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b c d e "Vojislav Seselj: Milosevic's hard-line ally". BBC News. 10 April 1999. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Pribićević 1999, p. 203.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, p. 204.

- ^ Pribićević, 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b c Pribićević 1999, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Bugajski 2002, p. 417

- ^ a b c Nichol, Ulric R. (2007). Focus on politics and economics of Russia and Eastern Europe. Nova. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-60021-317-5. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Pribićević 1999, p. 194.

- ^ "Profile: Vojislav Seselj". BBC News. London. 7 November 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Serbia vote: Parties and players". BBC News. 24 December 2003. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Hardliner elected Serbia speaker". BBC News. 8 May 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Radical Serbia speaker steps down". BBC News. 13 May 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Serbian Parliament Rejects UN Plan for Kosovo's Autonomy". Voice of America. Washington, D.C. 14 February 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Serbia ruling coalition collapses". BBC News. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Kosovo sparks early Serb election". BBC News. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "New Serbian cabinet focuses on EU". BBC News. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Kola, Paulin (8 July 2008). "Unlikely Serb allies put to the test". BBC News. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Jovanovic, Jovanovic; Foniqi-Kabashi, Blerta (30 June 2008). "Kosovo Serbs convene parliament; Pristina, international authorities object". Southeast European Times. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Nikolić i klub isključeni, Vučić odsutan". Mondo (in Serbian). 12 September 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Former SRS deputy leader Nikolic to form own party in Serbia". Southeast European Times. Belgrade. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Nikolić: I Vučić napustio radikale". Mondo (in Serbian). 14 September 2008. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Nikolic's new party to hold founding session next month in Belgrade". Southeast European Times. Belgrade. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Nikolic Is President of Serbian Progressive Party". Dalje.com. 21 October 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Tomislav Nikolic resigns as deputy leader of Serbian Radical Party, SAA ratified". European Forum for Democracy and Solidarity. 8 September 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ "Nikolić quits Radicals". B92. Belgrade. 12 September 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ "SRS ringing personnel changes". B92. Belgrade. 3 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ "New poll gives opposition parties lead". B92. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "West would like to see Nikolić in power". B92. 11 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Debakl šokirao Šešelja" (in Serbian). Vecernije novosti. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Parliament agrees to 3% electoral threshold". Serbian Monitor. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Cvetković, Ljudmila (5 April 2022). "Dobitnici i gubitnici izbora u Srbiji". Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbo-Croatian). Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Krstic, Jovana; Manojlovic, Mila; Heil, Andy (17 December 2023). "With Vucic Allies Poised to Dominate Serbian Elections, the Battle for Belgrade Takes on Extra Significance". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ "Ponovo zajedno: Šešelj najavio koaliciju SNS i SRS" [Together again: Šešelj announced the SNS and SRS coalition]. Vreme (in Serbian). 1 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Profesorka emerita: Saradnja SNS i SRS na lokalnim izborima radikalni oblik pokazivanja moći" [Professor emerita: SNS and SRS cooperation in local elections is a radical form of showing power]. Insajder (in Serbian). 1 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Nikolić, Maja (1 November 2023). "Kumovi ponovo na okupu: U borbi za Beograd, bivšim radikalima se priključuju originalni" [Godfathers together again: In the fight for Belgrade, former radicals are joined by original ones]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Извештај о укупним резултатима избора за одборнике Скупштине града Београда" (PDF). Градска изборна комисија. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Izborne LISTE". beograd.rs. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Thomas 1999, pp. 218–219.

- ^ "Massive Serbian protest against NATO & in favor of wartime leader Radovan Karadzic". Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Kirchick, James (8 April 2011). "'Why Right-Wing Serbs Love Qaddafi' – Kirchick in 'The New Republic'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ ОМЛАДИНА СРС УРУЧИЛА АМБАСАДИ СИРИЈЕ ПИСМО ПОДРШКЕ У БОРБИ ПРОТИВ ТЕРОРИЗМА. (in Serbian). Српска радикална странка. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Проф. др Војислав Шешељ: Апсолутно неприхватљиво да Србија уведе мораторијум на кампању повлачења признања "Косова"!". Vseselj.rs. 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Повеља о сарадњи СРС-а и Словеначке националне странке". RTS. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ "Serbian ministries, etc". rulers.org. B. Schemmel. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

Bibliography

edit- Bakić, Jovo (2009). "Extreme-right ideology, practice and supporters: case study of the Serbian Radical Party". Journal of Contemporary European Studies. 17 (2): 193–207. doi:10.1080/14782800903108643. S2CID 153453439.

- Bugajski, Janusz (2002). "Serbian Radical Party (SRP)". Political parties of Eastern Europe: a guide to politics in the post-Communist era. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 415–417. ISBN 978-1-56324-676-0.

- Konitzer, Andrew (2008). "The Serbian radical party in the 2004 local elections". East European Politics & Societies. 22 (4): 738–756. doi:10.1177/0888325408316528. S2CID 145777191.

- Lazić, Mladen; Vuletić, Vladimir (2009). "The nation state and the EU in the perceptions of political and economic elites: The case of Serbia in comparative perspective". Europe-Asia Studies. 61 (6): 987–1001. doi:10.1080/09668130903063518. S2CID 154590974.

- Nagradić, Slobodan (1995). Neka istorija sudi: razgovori sa liderima Srpske radikalne stranke. VIKOM. ISBN 9788679970053.

- Pribićević, Ognjen (1999). "Changing Fortunes of the Serbian Radical Right". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). The radical right in Central and Eastern Europe since 1989. Penn State. pp. 193–212. ISBN 978-0-271-01811-9.

- Samardzija, Anita; Robertson, Shanthi (2012). "Contradictory populism online: Nationalist and globalist discourses of the Serbian Radical Party's websites". Communication, Politics & Culture. 45 (1): 96.

- Stojarová, Vera (2016). The far right in the Balkans. Manchester University Press. pp. 5, 22, 35, 40, 48–50, 55–57, 64–65, 73, 82–83, 103–104, 106–112, 119, 152–155. ISBN 978-1-5261-1203-3.

- Thomas, Robert (1999). Serbia Under Milošević: Politics in the 1990s. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-341-7.

External links

edit- Serbian Radical Party Official website (in Serbian)