Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭, pinyin: Ǒuyì Zhìxù; 1599–1655) was a Chinese Buddhist scholar monk in 17th century China. He is considered a patriarch of the Chinese Pure Land School, a Chan master, as well as a great exponent of Tiantai Buddhism.[1][2][3] He was also one of the Four Eminent Monks of the Wanli Era, after Yunqi Zhuhong (1535–1615), Hanshan Deqing (1546–1623), and Daguan Zhenke (1543–1604).[4][5]

Grand Master (大師) Ouyi Zhixu | |

|---|---|

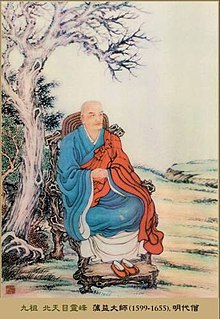

A portrait of Ouyi Zhixu | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 1599 South Zhili, Ming |

| Died | 1655 |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Lineage | Chinese Pure Land; Tiantai; Chan |

| Teachers | Xueling |

Zhixu is well known for his non-sectarian and syncretic writings, which draw on various traditions like Tiantai, Pure Land, Yogacara, and Chan, and also engage with Confucian, Daoist and Jesuit sources.[4][6]

Life

editOuyi was a native of Suzhou, Jiangsu province (South Zhili).[7][8] He was initially a student of Confucianism and rejected Buddhism, writing various anti-Buddhist tracts.[9] However, after reading the works of Yunqi Zhuhong, he changed his mind and burned his old writings.[7] When he was 19, his father died and Zhixu devoted himself completely to Buddhism, studying the sutras and practicing meditation.[7]

At the age of 24, he became a monk at Yunqi temple under Master Khan Xueling, a disciple of Hanshan Deqing.[7][8] During this 20s he studied Yogachara, practiced Chan based on the Shurangama Sutra, and he also experienced a great awakening during Chan meditation.[10][7]

After his mother died when he was 28, he experienced a spiritual crisis and turned to the Pure Land practice of nianfo (reciting the Buddha's name).[10] When he was 31, he drew lots to determine whether he should write a commentary on the Sutra of Brahma's Net based on Tiantai, Yogacara, Huayan or “a school of his own” (zili). He drew the lot for Tiantai.[11] According to Foulks, his use of lots (rather than lineage ties or doctrinal reasons) for writing from a specific Buddhist tradition suggests that he saw these schools of thought as "not only compatible but also interchangeable."[11]

In his 30s he studied the Tiantai school extensively, writing many commentaries and essays on Buddhist sutras.[7] He became deeply interested in mantrayana practice in his 30s, particularly the mantra of Kṣitigarbha.[2] Ouyi also became a public teacher during this time, writing and lecturing extensively.[2]

When he was 37 Ouyi experienced various bouts of illness which continued throughout the rest of his life. Over time, these experiences led him to shift his focus to Pure Land Buddhist practice.[12] At the age of 56, he underwent serious illness, after which he devoted himself almost entirely to Pure Land practice.[13] In his Preface to the Pure Land Repentance, Zhixu explains how in his later years he turned to Pure Land practice:

When I first aspired to the Mahayana, I diligently practiced for several years. Although I did not dare to be arrogant and claim to have arrived home, I felt that I had gained some strength in my practice. I then thought that I could not be reborn in the Pure Land. However, when I was seriously ill and close to death, I found that none of the methods I had practiced were of any use. I then single-mindedly aspired to return to the Pure Land. However, I did not abandon my original practice, hoping to combine Chan and Pure Land practice. After meeting Boshan, I fully understood the Chan sickness of the present age. I then resolutely abandoned Chan practice and cultivated Pure Land practice. Although I was criticized for being like a person who stops eating because of choking, I did not care.[14]

Ouyi died in 1656, at fifty-seven.[13]

Influence

editOne of Ouyi's main temples of residence was Lingfeng Temple (靈峯寺), located in Anji county, Zhejiang.[15] While Ouyi had previously written in his will that he wanted his remains to be burned and scattered in rivers as food for animals, his followers kept some of his bones as relics and placed them in a stupa at Lingfeng temple.[16] Today, this temple has been renovated, and it continues to celebrate its ties to master Ouyi. In 2007, a new reliquary courtyard and memorial hall for Ouyi were constructed.[15]

Ouyi Zhixu was very influential on Chinese Pure Land Buddhism. Important Pure Land Buddhist figures like Yinguang and Jingkong relied on his Commentary to the Amitabha Sutra and saw it as the definitive commentary to this sutra.[17] In the writings of Gukun 古崑 (fl. 1855-d. 1892), Ouyi was raised to the status of a patriarch of Pure Land Buddhism, and this status was also promoted by Yinguang.[17]

Ouyi Zhixu's work was influential on many later Chinese Buddhists including modern reformists like Taixu (1889–1947), Yinshun, and Hongyi (1880–1942).[18] The modern Chinese Buddhist teacher Sheng Yen (1930–2009) wrote his doctoral dissertation on Ouyi, and considered Ouyi to be one of the greatest modern Buddhist figures (alongside Taixu, Ouyang Jingwu, and Yinshun).[18][19]

His prolific writings and popularity with scholars made Ouyi one of the “four great eminent monks of the late Ming period" 明末四大高僧”.[17]

Teaching

editOuyi was an eclectic author who wrote on many Chinese Buddhist doctrines and methods. His numerous works cover Pure Land practice, bodhisattva precepts, Tiantai doctrine and practice, Chan meditation (relying on the Śūraṅgama Sūtra), repentance rituals, Dizang devotion, Consciousness-only philosophy and meditation as well as Chinese Esoteric Buddhism.[20][21] Ouyi was well versed in the different Buddhist traditions of China, and according to his autobiography, he saw himself as being part of an inclusive tradition that included diverse Buddhisms such as Tiantai, Chan, Vinaya, and Pure Land.[22] He had a non-sectarian view of the various forms of Buddhism, seeing them all as skillful means (upaya) for sentient beings with different potentials and circumstances.[13]

Furthermore, he saw the various elements of Chinese Mahayana as being harmonious and inseparable:

Meditation, the Teachings, and the Vinaya—these three are strung together continuously. They are not just spring orchids and fall chrysanthemums. Meditation is the Buddha’s mind, the Teachings are the Buddha’s words, and the Vinaya is the Buddha’s practice. How can this world have the mind but not the words or the practices? [23]

Numerous scholars see Ouyi as being affiliated with the Tiantai school. This is because his works show a deep influence from Tiantai ideas and doctrinal schemas, including the three truths, three contemplations, four teachings and so on.[24] However, other scholars refuse to pin him down to a single tradition, pointing to other influences in Ouyi's writings, including Vinaya, Chan and Pure Land ideas.[24]

Scholars like Beverley Foulks have argued that Ouyi ultimately did not consider himself to be a promoter of a single tradition in a sectarian sense, but instead should be seen as someone who saw his project as one “harmonizing the traditions” (zhuzong ronghe) and transcending specific sectarian distinctions.[25] Throughout his life, he studied and practiced multiple Chinese lineages, including Chan, Vinaya, Tiantai and Pure Land.[25]

The metaphysical foundation of Zhixu's Buddhist philosophy is the theory of "principle and nature" (理体), which is often expressed through varying terms such as "mind and nature" (心性), or "mind and body" (心体). These terms are used interchangeably to describe the fundamental principle that underlies all phenomena. This is the buddha-nature, the "body" of all dharmas, which is neither "empty" nor "not empty". It is beyond all descriptions and negations, and yet it is the source of all phenomena.[24] The basic source of this metaphysical theory is found in key Mahayana sources such as the Awakening of Faith, Śūraṅgama Sutra and the Lankavatara Sutra, both of which were commented upon by Ouyi.

Pure Land teaching

editAs with other Ming authors on Pure Land at the time, Ouyi Zhixu defended the view that Pure Land practice worked through a symbiotic combination of the "other power" of the Buddha Amitabha with the "self power" of a person's Buddhist practice.[7] This symbiosis was called “sympathetic resonance” (ganying 感應).[22] For Ouyi, this resonance is grounded in the classic Chinese Buddhist metaphysical view of Buddhahood as a holistic and harmonious ultimate reality. In his Commentary on the Amitābha-sūtra, Ouyi explains the Pure Land teaching by relying on the philosophy of the Awakening of Faith and on the Yogacara mind-only (cittamatra) school. According to Ouyi's commentary, there is only one ultimate reality: the Dharmakaya, or Buddha-Mind, also known as the One Mind. Everything is but a manifestation within the vast ocean of this One Mind, like waves, or ripples. This includes all worlds, Buddhas, sentient beings, times, places, and experiences across the entirety of existence. The One Mind perspective highlights our connection to the absolute while preserving the conventional realities.[26]

Although the Buddha-Mind encompasses all that exists, each of us possesses Buddha-nature, and our personal minds are infused with the Buddha-Mind, even if we fail to recognize it. Ignorance, delusion, and karmic obscurations only veil our awareness of this true nature. When we attempt to grasp or approach the One Mind using our limited, individual minds, it is akin to trying to scoop up the ocean with a teacup. This is why the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas guide us toward awakening using special skillful means meant for our dualistic minds. Every authentic Buddhist teaching is a skillful means tailored to specific circumstances, aiming to lead beings to the realization of the One Mind. Though these teachings differ in form and application, they share a singular intent.[26]

According to Ouyi, the best skillful means in our times for attaining the true Buddha Mind is to practice nianfo (buddha recollection):

Among all expedients [upayas], if we seek the most direct and the most complete, none is as good as seeking birth in the Pure Land through Buddha-remembrance [nianfo].[27]

This is because "the method of reciting the Buddha-name, applies to people of high, medium, and limited capacities. It encompasses both the level of phenomena, and the level of inner truth (noumenon), omitting nothing. It embraces both Zen Buddhism and Scriptural Buddhism, and leaves nothing out."[28] Ouyi also thinks this is the superior method because it is the most inclusive and accessible, "embracing people of all mentalities and the one that is easiest to practice."[29]

Ouyi taught a threefold schema of nianfo (buddha recollection):[30]

- Other Buddha Recollection: chanting the name of Amitabha while focusing on the Buddha’s merits and adornments as the object of contemplation.

- Self Buddha Recollection: contemplating one’s own intrinsic Buddha-nature, the formless originally enlightened mind.

- Self and Other Buddha Recollection: This reflects the unity of mind, Buddha, and sentient beings. It is a simultaneous contemplation of one's inner Buddha-mind and the external Buddha realms.

Furthermore, Ouyi also writes that "the name of Amitabha is the inherently enlightened true nature of sentient beings, and reciting the name of Amitabha reveals this enlightenment."[31] For Ouyi, the other-power of Amitabha Buddha (which is also inherent in our own mind) infuses his name with the force to lead beings to the pure land. Due to this, when someone recites the name (even those with low spiritual faculties), they merge with the Buddha, even without making an effort to meditate ("without bothering with visualization or meditation").[32] Thus, Ouyi writes:

We must realize that there is no name of Amitabha apart from the mind of infinite light and infinite life that is before us now at this moment, and there is no way for us to penetrate the mind of infinite light and infinite life that is before us now at this moment apart from the name of Amitabha. I hope you will ponder this deeply! [26]

For Ouyi, reciting the Buddha's name or Buddha-remembrance (nianfo) must be coupled with faith and vows (to attain birth in Sukhavati) for the optimum practice. Thus, Ouyi writes: “Without faith, we are not sufficiently equipped to take vows. Without vows, we are not sufficiently equipped to guide our practice. Without the wondrous practice of reciting the Buddha-name, we are not sufficiently equipped to fulfill our vows and to bring our faith to fruition."[33]

Ouyi writes that it is important to practice nianfo with a focused and undisturbed mind, as this will guarantee rebirth in the pure land.[34] However, he also held that even if our mind is scattered, reciting the name still plants wholesome seeds in the mind, due to the Buddha's mysterious power and compassion towards all:[35]

The compassion of the Buddhas is inconceivable, and the merits of their names are also inconceivable. Therefore, once you hear a Buddha-name, no matter whether you are mindful or not, or whether you believe in it or not, it always becomes the seed of an affinity with the truth. Moreover, when the Buddhas bring salvation to sentient beings, they do not sort out friends and enemies: they go on working tirelessly for universal salvation. If you hear the Buddha-name, Buddha is bound to protect you. How can there he any doubts about this?[36]

His moderate position is also evident in his understanding of how meditation (chan), doctrine (jiao) and precepts (lü) are all important and complementary elements of Buddhist practice.[7] Master Ouyi also explains how the ultimate principle (li, dharmakaya) is unified with conventional phenomena (shi) and thus, how the view of the pure land as the absolute reality is in perfect harmony with the view of the pure land as another realm one is reborn into after death:[37][38]

Believing in phenomena (事 shì) means having deep faith that this present single thought-moment appearing before one is inexhaustible, and therefore all the worlds of the ten directions manifested from the mind are also inexhaustible. The Land of Ultimate Bliss really does exist ten billion Buddha-lands away, a place of utmost purity and splendor. This is not like some parable from the Zhuangzi. This is called belief in phenomena. Believing in principle (理 lǐ) means having deep faith that although the Land of Ultimate Bliss is ten billion Buddha-lands away, it does not really exist outside oneself [out of] this single thought-moment of mind present before you, for the nature of this very single thought moment is truly all-encompassing (無外, “without an outside”).[39]

Repentance, precepts and mantra

editOuyi was actively involved in Tiantai repentance rituals. He wrote three works on repentance rites from a Tiantai perspective and practiced these rites extensively. This is because he was concerned that his past slandering of Buddhism (when he was a Confucian in his youth) had left a deep karmic imprint.[40] Ouyi practices various Tiantai repentance rituals throughout his life, but he performed Zunshi’s Amitābha repentance (Mituo chanfa) more often than the others.[41]

Ouyi was also deeply interested in Buddhist precepts and the rituals for conferring precepts. His works discuss the Tiantai concept of “precept-essence” (jie ti, 戒體) and how to maintain this essence pure. For Ouyi, maintaining ethical precepts remained a necessary aspect of the path, even if one relies on the Buddha's response power.[42]

Ouyi was also devoted to Dizang and his dhāraṇī. Dizang (Kṣitigarbha) was a bodhisattva known for saving people from hell and other bad rebirths and for having the power to transform bad karma.[40] Zhixu's interest in Chinese Esoteric Buddhism also extended to the Śūraṅgama Mantra, which he greatly respected. In his Zong Lun, Ouyi promotes the extensive recitation of this mantra, which he held would lead to samadhi and insight.[43] Along with these mantras, he also promoted the Amitābha Pure Land Mantra.[43]

Chan

editOuyi's Chan teaching has been seen by some scholars as an alternative tradition to the Linji school which was the dominant tradition during the Ming. Shengyen calls this Tathāgata Chan (rulai chan). Unlike the Linji teaching of gong’an (Jpn: kōan) practice, Ouyi's Chan method relied on the Śūraṃgama Sutra to understand Chan and attain enlightenment. His Chan is guided by figures like Yongming Yanshou (904–975) and Zibo Zhenke (1543–1603) and was practiced together with Pure Land Buddhism.[44]

On other Chinese religions

editOuyi promoted a non-sectarian worldview that exemplified the “harmonization of traditions” (zhuzong ronghe) and the “unity of the Three Teachings” (三教合一 sanjiao heyi), i.e. Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism.[11]

Ouyi also had a deep knowledge of Confucianism and in some of his writings he sought to integrate Buddhism and Confucianism, which he saw as deeply compatible and complementary.[5] Ouyi held that "the teachings of the Buddha and the sages are doing nothing else but urging us to exert our minds to the utmost."[8] For Ouyi, the profound meaning and ultimate source of Buddhism and Confucianism were the same true original mind.[45]

He also saw Buddhism and Confucianism as approaching the same truth in different ways, writing:

that the Great Way lies in the human mind is the only principle that has existence throughout the ages and is not privately owned by the Buddha and the sages. The unification of difference and convergence in sameness, is beyond the reach of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. In terms of reality, the Way is neither of this world, nor beyond this world. Thus, entering truth through the Way is called otherworldliness; entering the secular through the Way is called worldliness. Both the true and the secular are externalities, and externalities do not deviate from the way...Confucianism and Daoism both use true doctrines to protect the secular, so that the secular will not go against the truth; Buddhism approaches the secular to understand the truth, wherein the truth does not mix with the secular.[45]

Ouyi wrote a Chan interpretation of the Book of Changes (Yijing) and he said that this was "nothing else but an introduction of Chan into Confucianism, in order to entice Confucians to understand Chan".[45] Ouyi went as far as to write that "Confucianism, Daoism, Chan, Vinaya, Doctrinal Buddhism were nothing but yellow leaves and empty fists", meaning that they were all just skillful means (upaya) that could be used to attain the One Principle (yili).[46]

In his autobiography, Ouyi describes himself as "a follower of the eight negations". This term can have different connotations, including eight negations found in Madhyamaka sources ("neither arising nor ceasing, neither eternal nor impermanent, neither unitary nor different, neither coming nor going"). However, Ouyi also writes that this term can mean that he does not follow or study "Confucianism, Chan, Vinaya, and the Teachings." Foulks writes that this means Ouyi was "refusing to be categorized as Confucian or Buddhist (in any particular tradition), Ouyi instead espouses the most general religious identification of “follower” or “a person on the path” (daoren)".[47] According to Foulks, in his autobiography, Ouyi defends a "broad, nonsectarian religiosity" instead of focusing on any specific Buddhist tradition or seeing himself as part of any "school" (zong).[6]

Critique of Christianity

editOuyi wrote the Bixie ji (Collected Essays Refuting Heterodoxy) critiquing Christianity and defending Buddhism against the attacks of Christian Jesuit missionaries like Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) and Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[7] He especially focused on critiquing Christian theodicy and Christian ethics.[7][1] According to Beverley Foulks, Zhixu "objects to the way Jesuits invest God with qualities of love, hatred, and the power to punish. He criticizes the notion that God would create humans to be both good and evil, and finally he questions why God would allow Lucifer to tempt humans towards evil."[48] Zhixu generally writes his critiques of Christianity from a Confucian perspective, drawing on Confucian works instead of citing Buddhist sources.[1]

According to Foulks, Zhixu was also concerned with the ethical implications of Christianity, since he saw benevolence (ren 仁) as deriving from humans and their self-cultivation, but "if humans receive their nature from an external source, they can absolve themselves of ethical responsibility; moreover, since Jesuits disavow reincarnation, they further curtail the ability of humans to morally better themselves and render them entirely dependent on God or Jesus to absolve them of their wrongdoings."[1]

Works

editMaster Ouyi's oeuvre amounts to around seventy-five works.[13] This include treatises and commentaries on the teachings and texts of Mahayana Sutras, Chan, Tiantai, Yogacara, Vinaya, Bodhisattva Precepts, Pure Land as well as on Confucian classics. The Chinese Buddhist Book Bureau has collected all of his extant works into the Full Anthology of Master Ouyi (蕅益大师全集).[49]

Some of his important works include:

- Essential Explanations of the Amitābha-sūtra (Emituojing yaojie). This has been translated into English by Jonathan Christopher Cleary as Mind-seal of the Buddhas: patriarch Ou-i's commentary on the Amitabha Sutra.[50] The commentary "often uses T’ien-t’ai categories, and is firmly based on the ontology of Yogacara philosophy."[51]

- Ten essentials about the Pure Land (原本淨土十要 Jingtu shiyao), a collection of essential Pure Land teachings

- Explanation of the Keypoints to the Heart Sutra (Taisho # M555).[52]

- Meaning of the Lankāvatāra Sūtra, in one fascicle (楞伽经玄义).[53]

- Commentary on the Lankāvatāra Sūtra, in ten fascicles (楞伽经义疏).[53]

- Meaning of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, in two fascicles (楞严经玄義).[53]

- Elaboration of the Sentences of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, in ten fascicles (楞严经文句).[53]

- An Interpretation of the Mind Contemplation in the Diamond Sūtra, in one fascicle (金刚经观心释).[53]

- Discourse on the Diamond's Shattering of Emptiness, in two volumes 金刚破空论

- The Collected Interpretations of the Lotus Sutra in 16 fascicles (法华会义).[53]

- The Comprehensive thread of the Lotus Sutra, in one fascicle (法华经纶贯).[53]

- Annotation of the Brahma Net Sūtra (梵網經合註).[54]

- The Meaning of the Brahma Net Sūtra (梵網經玄义).[54]

- An Annotated Yogacara Summary of the Bodhisattva Precept Sūtra (菩萨戒本经笺要).[54]

- Pìxiè jí (闢邪集; Collected Essays Refuting Heterodoxy).[1]

- Essentials of Mind Contemplation in the Vijñāptimātratāsiddhi, ten fascicles (成唯识论观心法要).[53]

- Commentary on the Awakening of Faith, in six fascicles (起信论裂網疏).[53]

- Lingfeng zonglun (靈峰宗論), in 38 fascicles, which presents Ouyi's philosophical thought and views on religious practice.[55]

- Zhouyi chanjie (A Chan Explanation of the Book of Changes).[45]

- Sishu Ouyi Jie (Ouyi's Interpretation of the Four Books).[45]

- Commentary on the Divination Sutra (占察善惡業報經).[22]

- Xuanfo tu (選佛圖, Table for Buddha Selection), a board game based on the Shengguan tu 陞官圖 (Table of Bureaucratic Promotion).[56]

- Yuezangzhijin (阅 藏 知 津), explanations of the titles of the sutras in the Chinese Tripitaka.[57]

- Fahaiguanlan (法海觀澜), contains outlines of major Mahayana and Hinayana sūtras and shastras.[57]

- [Auto]biography of the Follower of Eight Negations (Babu daoren zhuan) – Ouyi's autobiography.[58]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Foulks McGuire, Beverley. Duplicitous Thieves: Ouyi Zhixu’s Criticism of Jesuit Missionaries in Late Imperial China. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2008, 21:55-75) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報第二十一期 頁55-75 (民國九十七年),臺北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN:1017-7132

- ^ a b c Cleary (1996), Introduction.

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 19.

- ^ a b McGuire, Beverley, "Ouyi Zhixu", Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism Online, Brill, retrieved 2023-01-06

- ^ a b William Chu. Syncretism reconsidered: The Four Eminent Monks and their syncretistic styles. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008).

- ^ a b Foulks 2014, pp. 23-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Ouyi Zhixu" in Buswell & Lopez (eds.) The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, 2014.

- ^ a b c Zhongjian Mou (2023), p. 399.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 32.

- ^ a b Cleary (1996), p. 33.

- ^ a b c Foulks 2014, pp. 24, 31.

- ^ Chen, Ying-Hsuan (Zhi-Guang Shih). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s The Essence of Teaching and Meditation (Jiaoguan Gangzong), pp. 25-26. Master's Thesis, Graduate Institute of Religious Studies, College of Humanities, Nanhua University, June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cleary (1996), p. 35.

- ^ Chen, Ying-Hsuan (Zhi-Guang Shih). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s The Essence of Teaching and Meditation (Jiaoguan Gangzong), pp. 19-21. Master's Thesis, Graduate Institute of Religious Studies, College of Humanities, Nanhua University, June 2019. Translated from the Chinese: [予初 志宗乘,苦參力究者數年,雖不敢起增上慢自謂到家,而下手工夫得力, 便謂淨土可以不生,逮一病濱死,平日得力處,分毫俱用不著,方乃一意 西歸。然猶不捨本參,擬附有禪有淨之科。至見博山後,稔知末代禪病, 索性棄禪修淨,雖受因噎廢飯之誚,弗恤也。]

- ^ a b Foulks (2014) p. 189.

- ^ Foulks (2014) pp. 120-121

- ^ a b c Ngai, M.-Y. M. (2010). From entertainment to enlightenment : a study on a cross-cultural religious board game with emphasis on the Table of Buddha Selection designed by Ouyi Zhixu of the late Ming Dynasty (T), pp. 20-21. University of British Columbia.

- ^ a b Master Sheng-yen (2002). Hoofprint of the Ox: Principles of the Chan Buddhist Path as Taught by a Modern Chinese Master, p. 11. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Ngai (2010), p. 23.

- ^ Wanyu, Zhang. "The Direct Explanation of Triṃśikā : an Annotated Translation of Ouyi Zhixu’s Weishi sanshi lun zhijie 唯識三十論直解", PHD Diss. Leiden University. 2019.

- ^ a b c "McGuire, Living Karma - the Religious Practices of Ouyi Zhixu (January 1, 2014) | US-China Institute". china.usc.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Chen Yingshan [陳英善]. "The Characteristics and Central Position of Ouyi Zhixu's Thought." [蕅益智旭思想的特質及其定位問題]. Journal of Chinese Literary and Philosophical Studies, Issue 8 (March 1996), pp. 227-256.

- ^ a b Foulks 2014, pp. 13-14.

- ^ a b c Cleary (1996), pp. 36-37.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 44.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 45.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 56.

- ^ Sheng Yen. "Master Ou Yi's Pure Land Thought" [藕益大師的淨土思想]. Modern Buddhist Academic Series [現代佛教學術叢刊], no. 65 (October 1980): 331–342. Taipei: Mahayana Culture, 1980.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 20.

- ^ Cleary (1996), pp. 37-38.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 16.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 39.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 39.

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 40.

- ^ Cleary (1996), pp. 53-54.

- ^ CBETA. No. 1762 [cf. No. 366] 佛說阿彌陀經要解 p. 4.

- ^ Translated from: 信事者,深信只今現前一念不可盡故,所以依心所現一切十方世界亦不可盡,實有極樂國土在十萬億土之外,最極清淨莊嚴不同莊生寓言,是名信事。 信理者,深信極樂國土雖在十萬億土之遠,而實不出我只今現前介爾一念心外,以吾現前一念心性實無外故。

- ^ a b Foulks 2014, pp. 53-55

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Jones, Charles B. Foundations of Ethics and Practice in Chinese Pure Land Buddhism. Journal of Buddhist Ethics v.10 (2003).

- ^ a b Chen, Ying-Hsuan (Zhi-Guang Shih). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s The Essence of Teaching and Meditation (Jiaoguan Gangzong), pp. 19-21. Master's Thesis, Graduate Institute of Religious Studies, College of Humanities, Nanhua University, June 2019.

- ^ Foulks 2014, pp. 13-14.

- ^ a b c d e Zhongjian Mou (2023), p. 400.

- ^ Charles S. Prebish, On-cho Ng (2022). The Theory and Practice of Zen Buddhism: A Festschrift in Honor of Steven Heine, p. 131. Springer Nature.

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Foulks, Beverley. Duplicitous Thieves: Ouyi Zhixu’s Criticism of Jesuit Missionaries in Late Imperial China. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal Archived 2021-11-27 at the Wayback Machine (2008, 21:55-75) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報第二十一期 頁55-75 (民國九十七年),臺北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN 1017-7132

- ^ Shi Yanming (author), Shi Sherry (translator). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thought on Bodhisattva Precepts, p. 63. Nan Hua University, Institute of Religious Studies.

- ^ Cleary, J.C.;Van Hien Study Group (1996). Mind-seal of the Buddhas: patriarch Ou-i's commentary on the Amitabha Sutra, The Amitabha Buddha Association of Queensland (Australia).

- ^ Cleary (1996), p. 34.

- ^ Pine, Red (2004), The Heart Sutra: The Womb of the Buddhas, Shoemaker 7 Hoard, ISBN 1-59376-009-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shi Yanming (author), Shi Sherry (translator). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thought on Bodhisattva Precepts, p. 65. Nan Hua University, Institute of Religious Studies.

- ^ a b c Shi Yanming (author), Shi Sherry (translator). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thought on Bodhisattva Precepts, Nan Hua University, Institute of Religious Studies.

- ^ Shi Yanming (author), Shi Sherry (translator). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thought on Bodhisattva Precepts, p. 66. Nan Hua University, Institute of Religious Studies.

- ^ Ngai, May-Ying Mary. From entertainment to enlightenment : a study on a cross-cultural religious board game with emphasis on the Table of Buddha Selection designed by Ouyi Zhixu of the late Ming Dynasty, 2010.

- ^ a b Shi Yanming (author), Shi Sherry (translator). A Study of Ouyi Zhixu’s Thought on Bodhisattva Precepts, p. 64. Nan Hua University, Institute of Religious Studies.

- ^ Foulks 2014, p. 22.

Sources

edit- Charles B. Jones (Trans.) Pì xiè jí 闢邪集: Collected Refutations of Heterodoxy by Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭, 1599–1655). Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 11 Fall 2009.

- Cleary, J.C.;Van Hien Study Group (1996). Mind-seal of the Buddhas: patriarch Ou-i's commentary on the Amitabha Sutra, The Amitabha Buddha Association of Queensland (Australia).

- Foulks McGuire, Beverley (2014). Living Karma: The Religious Practices of Ouyi Zhixu, Columbia University Press.

- Foulks McGuire, Beverley. Duplicitous Thieves: Ouyi Zhixu’s Criticism of Jesuit Missionaries in Late Imperial China. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2008, 21:55-75) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報第二十一期 頁55-75 (民國九十七年),臺北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN:1017-7132

- Lo, Y.K. (2008). Change beyond syncretism: Ouyi Zhixu's Buddhist hermeneutics of the Yijing Journal of Chinese Philosophy 35 (2) : 273-295. ScholarBank@NUS Repository.

- Ngai, M.-Y. M. (2010). From entertainment to enlightenment : a study on a cross-cultural religious board game with emphasis on the Table of Buddha Selection designed by Ouyi Zhixu of the late Ming Dynasty (T), pp. 20-21. University of British Columbia.

- Zhongjian Mou (2023). A Brief History of the Relationship Between Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Springer Nature.