Luis Ernesto Aparicio Montiel (born April 29, 1934), nicknamed "Little Louie", is a Venezuelan former professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a shortstop from 1956 to 1973 for three American League (AL) teams, most prominently the Chicago White Sox. During his ten seasons with the team, he became known for his exceptional defensive and base-stealing skills.[1][2] A 13-time All-Star,[3][a], he made an immediate impact with the team, winning the Rookie of the Year Award in 1956 after leading the league in stolen bases and leading AL shortstops in putouts and assists; he was the first Latin American player to win the award.

| Luis Aparicio | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

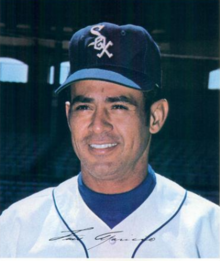

Aparicio with the Chicago White Sox, c. 1970 | |||||||||||||||

| Shortstop | |||||||||||||||

| Born: April 29, 1934 Maracaibo, Venezuela | |||||||||||||||

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |||||||||||||||

| MLB debut | |||||||||||||||

| April 17, 1956, for the Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||||

| Last MLB appearance | |||||||||||||||

| September 28, 1973, for the Boston Red Sox | |||||||||||||||

| MLB statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Batting average | .262 | ||||||||||||||

| Hits | 2,677 | ||||||||||||||

| Home runs | 83 | ||||||||||||||

| Runs batted in | 791 | ||||||||||||||

| Stolen bases | 506 | ||||||||||||||

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |||||||||||||||

| Teams | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Member of the National | |||||||||||||||

| Induction | 1984 | ||||||||||||||

| Vote | 84.6% (sixth ballot) | ||||||||||||||

Medals

| |||||||||||||||

From 1956 to 1962, Aparicio and second baseman Nellie Fox formed one of the most revered double play duos in major league history.[4][5][6] As the team's leadoff hitter and defensive star, he provided a spark to the "Go-Go" White Sox, helping to lead them to their first pennant in 40 years in 1959, finishing second to Fox in the Most Valuable Player (MVP) voting. His 56 stolen bases that season were more than twice as many as any other major league player, and the most by any player in 16 years; he tied the White Sox club record, with the mark not being surpassed until 1983. Aparicio led the AL in stolen bases a record nine consecutive seasons to begin his career, becoming the first player since the 1920s to steal 50 bases four times. Traded to the Baltimore Orioles before the 1963 season, he set a franchise record with 57 steals in 1964, then played a major role in helping the club to its first World Series title in 1966. Aparicio won nine Gold Glove Awards,[7][8] setting a league record since matched only by Omar Vizquel; he led the AL in fielding percentage eight consecutive years, and in assists seven times, putouts four times and double plays twice, and in 1960 became the first AL shortstop in 25 years to post 550 assists.

When he retired, Aparicio ranked second to Ty Cobb in AL history in career at bats (10,230), fifth in games played (2,599) and seventh in singles (2,108); his 506 stolen bases trailed only Cobb and Eddie Collins among AL players. He set major league records for career hits and total bases as a shortstop that were later broken by Derek Jeter and Cal Ripken Jr. respectively. His 2,581 games as a shortstop were a major league record until 2008, and the AL record until 2014. He held the major league records for career assists (8,016) and double plays (1,553) until Ozzie Smith passed him in 1994 and 1995; he still holds the AL records for assists, putouts (4,548), and total chances (12,930), though Ripken broke his AL double play mark in 1996. Aparicio's career fielding percentage (.972) ranked second in AL history when he retired, one point behind Lou Boudreau. Legendary hitter Ted Williams called Aparicio "the best shortstop he had ever seen".[9] He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984, the first Venezuelan player to be so honored.[1]

Early life

editAparicio was born in Maracaibo, Zulia State, Venezuela.[2] His father, Luis Aparicio Sr., was a notable shortstop in Venezuela and owned a Winter League team with Aparicio's uncle, Ernesto Aparicio.[10] At the age of 19, Aparicio was selected as a member of the Venezuelan national team in the 1953 Amateur World Series held in Caracas; Venezuela took the silver medal in the tournament.[2] He signed to play for the local professional team in Maracaibo alongside his father in 1953. In a symbolic gesture during the team's 1953 home opener, his father led off as the first hitter of the game, took the first pitch, and had Aparicio Jr. take his place at bat.[2]

Major league career

editChicago White Sox (1956–1962)

editThe Cleveland Indians had been negotiating to sign Aparicio, but Indians General Manager Hank Greenberg expressed the opinion that he was too small to play in the major leagues.[2] Chicago White Sox general manager Frank Lane, on the recommendation of fellow Venezuelan shortstop Chico Carrasquel, then signed Aparicio for $5,000 down and $5,000 in first-year salary.[11] After only two years in the minor leagues, he made his major league debut at the age of 22, replacing Carrasquel as the White Sox shortstop in 1956.[2] Aparicio would lead the American League in stolen bases, assists and putouts, and won both the AL Rookie of the Year and The Sporting News Rookie of the Year awards.[7][12][13] He was the first Latin American player to win the Rookie of the Year Award.[2]

Aparicio quickly became an integral member of the Go-Go White Sox teams of the mid-1950s, who were known for their speed and strong defense. Over the next decade, Aparicio set the standard for the spray-hitting, slick-fielding, speedy shortstop.[10] He combined with second baseman Nellie Fox to become one of the best double play combinations in the major leagues.[14][15] Aparicio once again led the AL in stolen bases and assists in 1957 as the White Sox held first place until late June before finishing the season in second place behind the New York Yankees.[14][16] On September 7 against the Kansas City Athletics, he hit two home runs for the only time in his career, leading off the game with an inside-the-park home run and adding a three-run shot in the 4th inning as the White Sox won 8-2.

In 1958, Aparicio earned recognition as one of the top shortstops in the major leagues when he was selected to be the AL's starting shortstop in the All-Star Game.[17] The White Sox once again finished the season in second place behind the Yankees, after being in last place on June 14.[18] Aparicio again led the league in stolen bases, assists and putouts, and won his first Gold Glove Award.[7][19]

Aparicio was the team leader when the "Go-Go" White Sox won the AL pennant in 1959, finishing the regular season five games ahead of the Cleveland Indians.[20] After stealing 56 bases to tie Wally Moses' 1943 team record, he was runner-up to Fox in the Most Valuable Player Award balloting.[21] Aparicio was selected as a starting All-Star for the second time and also won a second Gold Glove Award.[22][23] He posted a .308 batting average in the 1959 World Series as the White Sox were defeated by the Los Angeles Dodgers in a six-game series.[24] The White Sox record stood until Rudy Law stole 77 bases in 1983. When Aparicio stole 50 bases in his first 61 attempts in 1959, the term "Aparicio double" was coined to represent a walk and a stolen base.[25] Since the 2019 death of teammate Johnny Romano, Aparicio has been the last surviving player to play with the White Sox in the 1959 World Series.

In 1960 and 1961, Aparicio continued to be one of the top shortstops in the league, finishing at or near the top in fielding percentage and assists. His 1960 total of 551 assists was the highest in the major leagues since 1943, and the highest AL total since White Sox star Luke Appling recorded 556 in 1935; the last season above 550 previous to that had been in 1911. In 1962, Aparicio showed up overweight and had an off year, and the White Sox offered him a reduction in salary for the 1963 season.[26] An enraged Aparicio said that he would quit rather than accept a decrease in pay and demanded to be traded.[26] The White Sox eventually traded him to the Baltimore Orioles with Al Smith for Hoyt Wilhelm, Ron Hansen, Dave Nicholson and Pete Ward in January 1963.[27]

Baltimore Orioles (1963–1967)

editAparicio regained his form in Baltimore and continued to lead the league in stolen bases and in fielding percentage, producing a career-high .983 fielding percentage in 1963.[7] Together with Brooks Robinson and Jerry Adair, he was part of one of the better defensive infields in baseball.[28][29] In 1964, he led the league in stolen bases for a ninth consecutive year, with his 57 steals breaking George Sisler's franchise record of 51 set with the 1922 St. Louis Browns, and won his sixth Gold Glove Award.[7][30] Aparicio posted a .276 batting average with 182 hits in 1966, tied with teammate Frank Robinson for the second-most hits in the league behind Tony Oliva and won a seventh Gold Glove Award as the Orioles clinched their first American League pennant.[31][32][33] He finished ninth in the MVP balloting, in which teammates took the top three spots, and helped the Orioles sweep the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1966 World Series.[34][35]

Return to White Sox (1968–1970)

editWith the emergence of Mark Belanger at shortstop, Aparicio was traded back to the White Sox along with Russ Snyder and John Matias for Don Buford, Bruce Howard and Roger Nelson on November 29, 1967.[36] He continued to play well defensively, leading the league in range factor in 1968 and 1969.[7] On May 15, 1969, he picked up his 2,000th hit in a 10-inning, 2-1 loss in Detroit. Aparicio had his best overall offensive season in 1970, scoring 86 runs and finishing fourth in the AL batting race with a career-high .313 average.[7] In addition, he earned his eighth All-Star berth that year, as well as his ninth Gold Glove.[37][38] On September 25, in the first game of a doubleheader against the Milwaukee Brewers, Aparicio broke Luke Appling's record of 2,218 games at shortstop as the White Sox won 5-1; it was his last game of the season. Despite the White Sox finishing in last place, Aparicio finished 12th in the MVP balloting.[39][40]

Boston Red Sox (1971–1973)

editAfter three seasons with the White Sox, Aparicio was traded to the Boston Red Sox for Luis Alvarado and Mike Andrews on December 1, 1970.[41] In 1971, Aparicio had a career-high six runs batted in (RBI) on April 10 against the Indians in Cleveland, hitting a 2nd-inning grand slam followed by a 2-run double in the seventh inning.[42] In late May, he was one at bat from tying the longest major league hitless streak for non-pitchers, held by Bill Bergen with 45 in 1909 with the Brooklyn Superbas, by going without a hit in 44 at bats.[43] He ended the streak with a 2nd-inning single against the Kansas City Royals on June 1. During the season, he broke Appling's record of 1,424 career double plays. He hit only .232 for the year, the second-lowest average in his career.[7]

In 1972, Aparicio broke Appling's major league record of 3,328 total bases as a shortstop, and Bill Dahlen's record of 7,505 assists; he also made his 2,500th hit on August 15 in a 3-0 road win over the Texas Rangers. However, he also made a late-season baserunning blunder that contributed to the Red Sox losing the 1972 American League Eastern Division title by a half-game to the Detroit Tigers.[44] In an October 2 game against Detroit, Aparicio fell while rounding third base on an apparent triple by Carl Yastrzemski, leading to Yastrzemski being tagged out as he tried to retreat to second base.[45] In his last year as an active player in 1973, Aparicio hit for a .271 average and stole his 500th base, against the New York Yankees on July 5.[46] He also broke Appling's major league record of 2,594 hits as a shortstop. Aparicio retired at the end of the season at the age of 39.[7]

Career statistics

editAparicio played for 18 major league seasons in 2,599 games, accumulating 2,677 hits in 10,230 at bats for a .262 career batting average along with 394 doubles, 83 home runs, 791 runs batted in, 1,335 runs and 506 stolen bases.[7] He ended his career with a .972 fielding percentage.[7] Aparicio led AL shortstops eight times in fielding percentage, seven times in assists, and four times in range factor and putouts.[7] He led the league in stolen bases in nine consecutive seasons (1956–1964) and won the Gold Glove Award nine times (1958–1962, 1964, 1966, 1970).[7][47][48] Aparicio was also a ten-time All-Star[7][49] (1958–1964, 1970–1972); he was named to 13 out of 14 All-Star Games (two All-Star Games were held from 1959 through 1962), was the starting shortstop in six All-Star games and played in 10 games (he didn't play in the second All-Star game in 1960 and was injured and replaced in the 1964 and 1972 games and didn't play).

At the time of his retirement, Aparicio was the all-time leader for games played, assists and double plays by a shortstop and the all-time leader for putouts and total chances by an American League shortstop.[1] His nine Gold Glove Awards set an AL record for shortstops that was tied by Omar Vizquel in 2001.[48] He tied the record of most seasons leading the league in fielding average by shortstops with 8, previously set by Everett Scott and Lou Boudreau.[50]

His 2,583 games played at shortstop stood as the major league record from his retirement in 1973 until May 2008, when it was surpassed by Omar Vizquel.[50] His 2,677 hits was also the major league record for players from Venezuela, until it was surpassed by Vizquel in 2009.[51] His 2,673 hits as a shortstop were a record until Derek Jeter broke it on August 17, 2009.[52] He had 13 consecutive seasons with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title and an on-base percentage less than .325, a major league record (his career OBP was slightly better than the shortstop average during his era; .311 vs .309). A more impressive streak was his 16 straight seasons with more than 500 plate appearances, tied for fifth best in major league history. Aparicio never played any defensive position other than shortstop.[53]

- AL leader in at bats (1966)

- AL leader in singles (1966)

- AL leader in sacrifice hits (1956, 1960)

- AL leader in stolen bases (1956–1964)

- AL leader in putouts as shortstop (1956, 1958, 1959, 1966)

- AL leader in fielding average as shortstop (1959–1966)

Awards and honors

editAparicio was inducted to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984, the first native of Venezuela to be honored.[1] The White Sox also retired Aparicio's uniform number 11 that year. In 2010, the White Sox gave number 11 to shortstop Omar Vizquel, with Aparicio's permission. Vizquel said that wearing the number would preserve the name of a great Venezuelan shortstop. Aparicio commented, "If there is one player who I would like to see wear my uniform number with the White Sox, it is Omar Vizquel. I have known Omar for a long time. Along with being an outstanding player, he is a good and decent man."[54]

In 1981, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included Aparicio in their book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time. In 1999, The Sporting News did not include him on their list of The Sporting News list of Baseball's 100 Greatest Players, but Major League Baseball did include him that year as one of eight shortstops nominated for their All-Century Team.[55]

The 2001 Major League Baseball All-Star Game was dedicated jointly to Aparacio, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, and Tony Perez. Along with Ferguson Jenkins, they threw out the ceremonial first pitch to end the player introduction ceremonies.

In 2003, Aparicio was inducted into the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.[citation needed] In 2004, the first annual Luis Aparicio Award was presented to the Venezuelan player who recorded the best individual performance in Major League Baseball, as voted on by sports journalists in Venezuela.

He threw out the ceremonial first pitch at Game 1 of the 2005 World Series, the first World Series game to be played in Chicago by the White Sox since the 1959 World Series, when Aparicio had been their starting shortstop.[56]

In honor of Aparicio's stealing abilities, a walk and a stolen base was known as an "Aparicio double"[57]

In 2006, two bronze statues depicting Aparicio and former White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox were unveiled on the outfield concourse of U.S. Cellular Field in Chicago. Fox's statue shows him flipping a baseball toward Aparicio, while Aparicio's statue shows him preparing to receive the ball from Fox.[58] Artist Gary Tillery sculpted the statue of Aparicio.[59]

In 2007, Aparicio was inducted into the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame.[60]

There is a stadium in Maracaibo, Venezuela, bearing his father's name. The full name of the stadium is Estadio Luis Aparicio El Grande (Luis Aparicio "the Great" Stadium) in honor to Luis Aparicio Ortega.[61] Also, the sports complex where the stadium is located is named Polideportivo Luis Aparicio Montiel. There are also several streets and avenues bearing his name throughout Venezuela.

In 2015, Empresas Polar and Fenix Media released a documentary, Thirty Years of Immortality, which features testimonials from many major leaguers, friends, and family, on the day that Aparicio was announced as being voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Director Isaac Bencid said, "It was a good time to honor Mr. Aparicio because it was the first time he had a documentary made of his life. I want to make people know in Venezuela. I think sometimes that you in the United States know more about Mr. Aparicio than many Venezuelans. Baseball is very important down there but a lot of young people in Venezuela don't know Mr. Aparicio. What we want to do is honor him and make people know about him."[62]

Following the death of Willie Mays on June 18, 2024, Aparicio has been the oldest living Baseball Hall of Famer.[63]

See also

edit- List of Gold Glove middle infield duos

- List of Gold Glove Award winners at shortstop

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career plate appearance leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players from Venezuela

- List of Major League Baseball retired numbers

Notes

edit- ^ MLB held two All-Star Games from 1959 through 1962

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Luis Aparicio". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Luis Aparicio at the SABR Baseball Biography Project , by Leonte Landino, Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame, Luis Aparicio, "10-time All-Star" [1] Retrieved April 17, 2015

- ^ "Were Trammell and Whitaker best all-around double-play combo ever? (#10)". CBS Sports. December 22, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Ground Ball Up the Middle - The Top 50 SS-2B Combos Since 1960 (#6)". Bleacher Report. December 23, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "The Greatest Double-Play Duos in MLB History (#8)". Complex. April 29, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Luis Aparicio". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame, Luis Aparicio [2] Retrieved April 17, 2015

- ^ Eldridge, Larry (January 10, 1984). "Shortstop Aparicio may be short hop from Hall of Fame, finally. The Christian Science Monitor. [3] Retrieved April 17, 2015

- ^ a b Rogin, Gilbert (May 9, 1960). "Happy Little Luis". Sports Illustrated. Sports-Illustrated.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press. p. 599. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- ^ "1959 Rookie of the Year Award voting results". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Rookie of the Year Award by The Sporting News". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Terrell, Roy (May 13, 1957). "The Go-sox Go Again". Sports Illustrated. Sports-Illustrated.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Woodcock, Les (August 10, 1959). "Two For The Pennant". Sports Illustrated. Sports-Illustrated.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1957 Chicago White Sox Season". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1958 All-Star Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1958 Chicago White Sox Season". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1958 Gold Glove Award Winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1959 American League Final Standings". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1959 American League Most Valuable Player Award voting results". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1959 Gold Glove Award Winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1959 All-Star Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1959 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Dickson, Paul (1989). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. United States: Facts on File. p. 12. ISBN 0816017417.

- ^ a b "If Luis Aparicio Clubhouse Lawyer, Baltimore Would Like Bench Full". Times Daily. NEA. April 21, 1963. p. 2. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ "Luis Aparicio Trades and Transactions". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Kuenster, John (June 2004). Shortstop and Third Base Team Mates Who Led League in Fielding. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Kuenster, John (June 2009). Middle Infield Tandems That Won Fielding Titles, Same Season. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "1964 Gold Glove Award Winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1966 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1966 Gold Glove Award Winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1966 American League Final Standings". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1966 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1966 American League Most Valuable Player Award voting results". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Trade Shuffle Sends Aparicio To White Sox," Associated Press (AP), Thursday, November 30, 1967. (Scroll down to page 14.) Retrieved April 17, 2020

- ^ "1970 Gold Glove Award Winners". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1970 All-Star Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1970 American League Final Standings". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "1970 American League Most Valuable Player Award voting results". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Bob Aspromonte Joins New York," The New York Times, Wednesday, December 2, 1970. Retrieved March 5, 2020

- ^ Prime, Jim; Nowlin, Bill (March 2001). Tales From The Red Sox Dugout. Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 1-58261-348-6. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Fimrite, Ron (June 14, 1971). "Even The President Worried". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "October 2, 1972 Red Sox-Tigers box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Today In History – Base-Running Blunders Doom Boston". fenwayfanatics.com. October 2, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "July 5, 1973 Red Sox-Yankees box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Stolen Base Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "Multiple Winners of the Gold Glove Awards". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Donnelly, Patrick. SportsData LLC. (2012). Midsummer Classics: Celebrating MLB's All-Star Game. 1959–1962: "all players who were named to the AL or NL roster were credited with one appearance per season" "Midsummer Classics: Celebrating MLB's AllStar Game - Sports Data". Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.. SportsData https://www.sportsdatallc.com. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Kuenster, John (June 2005). Shortstops By The Numbers. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Beck, Jason. "Miggy tops in MLB hits for Venezuelan player". mlb.com. MLB Advanced Media, LP. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler (August 17, 2009). "Milestone for Jeter in an Otherwise Lost Day for the Yankees". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ "Luis Aparicio Biography". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Luis Aparicio's number comes back from retirement for one... last... job". ESPN. February 11, 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "The Major League Baseball All-Century Team". MLB.com. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Aparicio pays visit to Guillen". MLB.com. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Dickson, Paul (1989). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. New York: FactsOnFile Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0816017417.

- ^ "Aparicio, Fox honored with statues". MLB.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Luis Aparicio". Fine Art Studio of Rotblatt Amrany. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "Hispanis Heritage Baseball Museum". Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ "Estadio Luis Aparicio El Grande". Mundo-Andino.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Film Fest a hit for fans, filmmakers".

- ^ "Willie Mays, a baseball giant, dies at 93". MLB.com. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Luis Aparicio at the SABR Baseball Biography Project , by Leonte Landino, Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- "Happy Little Luis", Sports Illustrated, May 9, 1960

- "Looie Is Queeck In Head, Too", Baseball Digest, August 1964

- "Baseball's Most Durable Shortstop – Luis Aparicio", Baseball Digest, July 1970

- "The Game I'll Never Forget", Baseball Digest, September 1972

External links

edit- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Venezuelan Professional Baseball League statistics

- Luis Aparicio at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Luis Aparicio at the SABR Baseball Biography Project