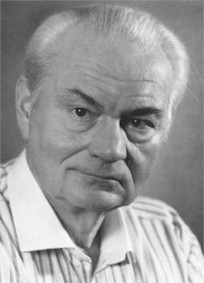

Heinz G. Konsalik, pseudonym of Heinz Günther (28 May 1921 – 2 October 1999) was a German novelist. Konsalik was his mother's maiden name.[1]

During the Second World War he was a war correspondent, which provided many experiences for his novels.[2]

Many of his books deal with war and showed the German human side of things as experienced by their soldiers and families at home, for instance Das geschenkte Gesicht (Mask My Agony / The Changed Face) which deals with a German soldier's recovery after his sledge ran over an anti-personnel mine and destroyed his face, and how this affected his relationship with his wife at home. It places no judgment on the German position in the war and simply deals with human beings in often desperate situations, doing what they were forced to do under German military law. Der Arzt von Stalingrad (The Naked Earth / The Doctor of Stalingrad) made him famous and was adapted as a movie in 1958. Some 83 million copies sold of his 155 novels made him the most popular German novelist of the postwar era and many of his novels were translated and sold through book clubs. He is buried in Cologne.

Life and work in the Nazi era

editAt the age of 16, Günther wrote feature articles for Cologne newspapers. In 1938 he published what he considered his “first usable poem.”[3] On 31 August 1939 he completed the heroic tragedy Der Geuse (“The Beggar”) as a senior secondary student. He then joined the Hitler Youth, Area 11, Middle Rhine Valley. In December 1939 he started working for the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police.[4] His next drama, which he completed in March 1940, was called Gutenberg. In the same year Günther sought membership in the Nazi writer's union, the Reich Chamber of Writers (Reichsschrifttumskammer) but was initially rejected due to the limited scope of his literary work. Later, however, having met the requirements, he received the chamber membership required for regular publication of literary works.[3]

After graduating from the Humboldt-Gymnasium in Cologne, which required membership in the Nazi party and the teaching of its discredited but then pervasive racial theories, he studied medicine and later switched to theatre studies, literary history and German literature. During World War II he became a war correspondent in France and later came to the Eastern Front as a soldier, where he suffered a serious arm wound at Smolensk in the Soviet Union.[5] He was later to describe his wartime experiences in Russia as a “monstrous school.”[6]

Selected works

edit- Der Mann, der sein Leben vergaß (1952)

- Die schweigenden Kanäle (1954)

- Der Arzt von Stalingrad (1956, The Naked Earth, a.k.a. The Doctor of Stalingrad)

- Viele Mütter heißen Anita (1956)

- Sie fielen vom Himmel (1958, They Fell from the Sky)

- Die Rollbahn (1959, Highway to Hell)

- Schicksal aus zweiter Hand (1959)

- Strafbataillon 999 (1959, Straf-Battalion 999)

- Agenten kennen kein Pardon (1960)

- Ich beantrage Todesstrafe (1960)

- Der rostende Ruhm (1960)

- Der letzte Karpatenwolf (1961, The Last Carpathian Wolf)

- Dr. med. Erika Werner (1962, Doctor Erica Werner)

- Fronttheater (1962, Front-Line Theatre)

- Das geschenkte Gesicht (1962, Mask My Agony, a.k.a. The Changed Face)

- Der Himmel über Kasakstan (1962, Skies over Kazakstan)

- Natascha (1962, Natasha)

- Entmündigt (1963, Certified Insane)

- Zerstörter Traum vom Ruhm (1963)

- Das Herz der 6. Armee (1964, The Heart of the 6th Army)

- Privatklinik (1965, Private Hell)

- Liebesnächte in der Taiga (1966)

- Zum Nachtisch wilde Früchte (1967)

- Das Schloß der blauen Vögel (1968)

- Bluthochzeit in Prag (1969)

- Liebe am Don (1970, Love on the Don)

- Der Wüstendoktor (1971, The Desert Doctor)

- Wer stirbt schon gerne unter Palmen (1972)

- Der Leibarzt der Zarin (1972)

- Aus dem Nichts ein neues Leben (1973)

- Ninotschka, die Herrin der Taiga (1973)

- Des Sieges bittere Tränen (1973)

- Ein Sommer mit Danica (1973, Summer with Danica)

- Ein toter Taucher nimmt kein Gold (1973)

- Eine Urwaldgöttin darf nicht weinen (1973)

- Engel der Vergessenen (1974, Angel of the Damned)

- Ein Komet fällt vom Himmel (1974)

- Die Verdammten der Taiga (1974, The Damned of the Taiga)

- Wen die schwarze Göttin ruft (1974)

- Alarm! Das Weiberschiff (1976)

- Das Doppelspiel (1977)

- Eine glückliche Ehe (1977, The War Bride)

- Die schöne Ärztin (1977, The Ravishing Doctor)

- Sie waren zehn (1979, Strike Force Ten)

- Die Erbin (1979, The Heiress)

- Die dunkle Seite des Ruhms (1980)

- Frauenbataillon (1981)

- Ein Kreuz in Sibirien (1983)

- Die strahlenden Hände (1984)

- Das Bernsteinzimmer (1988)

- Der schwarze Mandarin (1994)

Filmography

edit- The Doctor of Stalingrad, directed by Géza von Radványi (1958, based on the novel Der Arzt von Stalingrad)

- Strafbataillon 999, directed by Harald Philipp (1960, based on the novel Strafbataillon 999)

- Love Nights in the Taiga, directed by Harald Philipp (1967, based on the novel Liebesnächte in der Taiga)

- Champagner für Zimmer 17, directed by Michael Thomas (1969, based on the novel Ein heißer Körper zu vermieten - written as Jens Bekker)

- Schwarzer Nerz auf zarter Haut, directed by Michael Thomas (1970, based on the novel Schwarzer Nerz auf zarter Haut - written as Henry Pahlen)

- Slaughter Hotel, directed by Fernando Di Leo (1971, based on the novel Das Schloß der blauen Vögel)

- No Gold for a Dead Diver, directed by Harald Reinl (1974, based on the novel Ein toter Taucher nimmt kein Gold)

- Wer stirbt schon gerne unter Palmen, directed by Alfred Vohrer (1974, based on the novel Wer stirbt schon gerne unter Palmen)

- Vreemde Wêreld, directed by Jürgen Goslar (1974, based on the novel Entmündigt)

- The Secret Carrier, directed by Franz Josef Gottlieb (1975)

- Docteur Erika Werner, directed by Paul Siegrist (TV miniseries, 1978, based on the novel Dr. med. Erika Werner)

- La Passion du docteur Bergh, directed by Josée Dayan (TV film, 1996, based on the novel Der rostende Ruhm)

- One Step Too Far, directed by Udo Witte (TV film, 1998, based on the novel Eine Sünde zuviel - written as Jens Bekker)

- China Dream, directed by Otto Alexander Jahrreiss (TV film, 1998, based on the novel Der schwarze Mandarin)

Notes

edit- ^ "Heinz G. Konsalik, 78, German Novelist - The New York Times". The New York Times. 4 October 1999.

- ^ p. 169 Weidhaas, Peter; Gossage, Carolyn & Wright, Wendy A. A History of the Frankfurt Book Fair Dundurn Press Ltd., 2007

- ^ a b Otto Koehler: Gestapomann Konsalik. In: Die Zeit, issue 32/1996, 2 August 1996.

- ^ Matthias Harder: Erfahrung Krieg: Zur Darstellung des Zweiten Weltkrieges in den Romanen von Heinz G. Konsalik (“War experience: Depicting the Second World War in the novels of Heinz G. Konsalik”. Königshausen & Neumann, S. 41.

- ^ Gunar Ortlepp: Urwaldgöttin darf nicht weinen (“A jungle goddess mustn't cry”) in Der Spiegel, 1976:50, pp. 219-221, 6 December 1976.

- ^ Die Ein-Mann-Traumfabrik – Porträt des Bestseller-Autors Heinz G. Konsalik (“One-man dream factory: Portrait of the best-selling author Heinz G. Konsalik”) in Die Zeit, 3 October 1980