Gioachino Greco (c. 1600 – c. 1634), surnamed Cusentino and more frequently il Calabrese,[2] was an Italian chess player and writer. He recorded some of the earliest chess games known in their entirety. His games, which never indicated players, were quite possibly constructs,[3] but served as examples of brilliant combinations.[4]

Greco was very likely the strongest player of his time, having played (and defeated) the best players of Rome, Paris, London, and Madrid.[5] Greco's writing was in the form of manuscripts for his patrons, in which he outlined the rules of chess, gave playing advice, and presented instructive games.[6] These manuscripts were later published to a wide audience and became massively influential after his death.[4]

Name

editThe name "Greco" is often assumed to be indicative of a Greek heritage. Indeed, Calabria, the region in which Greco was born, has a long history of Greek immigration and use of Greek as the vernacular. One prominent writer, Willard Fiske, even suggests (in The Book of the First American Chess Congress, 1859) that Greco was born in Morea, Greece, before moving to Calabria. Fiske gives no specific evidence for this claim, however; neither do other writers claiming that in this case "Greco" signified "Greek".[7] The origin of "Greco" is therefore largely speculative.

Greco's other names have more concrete origins. "Cusentino" is known from the Corsini manuscript, and means that he was born near Cosenza.[7] il Calabrese, literally "the Calabrian", meant that Greco was from the Calabria region.[8]

Life

editLittle is known about the life of Greco. The most reliable information about his life comes from his manuscripts.[10] He was born around 1600 in Celico, Italy. Greco apparently showed an early aptitude for chess, leaving home uneducated[10] and at a young age to make a living abroad.[11] By 1620 Greco had become experienced enough to write his earliest dated manuscript, Trattato Del Nobilissimo Gioco De Scacchi...,[12] copies of which were given to his patrons in Rome.[13]

Greco is said to have traveled to Paris,[14] although this visit is conspicuously unattested by existing manuscripts.[10] There he continued to find great success. His victories over the strongest French players – among them the Duc de Nemours, M. Arnault le Carabin, and M. Chaumont de la Salle – granted him both fame and riches.[12] By 1622 Greco was travelling to England with a large sum of money; in Paris he had gained the equivalent of 5,000 crowns.[5][14]

Greco was apparently waylaid during this journey, however, resulting in the loss of his newfound wealth. Undeterred, he continued to London and played the English chess elite. During his stay in London, Greco began recording entire chess games rather than single instructive positions, as had been the usual manner.[12]

Greco returned to Paris in 1624 and began rewriting his collection of manuscripts. It is unclear whether he actually played these games – to modern eyes, his opponents' play seems dubious at best.[15] The games' provenance is perhaps inessential; having composed them, Greco was "certainly capable of playing them" on a board.[16]

Not one to remain in one place for long, Greco left Paris for the court of Philip IV in Spain. Greco managed to defeat all his opponents there, as well.[17] By this point Greco had shown himself to be the greatest player in Europe with victories over the champions of Rome, Paris, London, and Madrid.[5]

Having conquered the Old World, Greco traveled to the New. Greco is said to have succumbed to disease in the West Indies soon after arriving. The exact date of his death is unknown, but most sources have him dead by 1634.[5] His chess earnings were given to the Jesuits.[17]

Legacy

editGreco was a remarkable chess player who lived during the era between Ruy López de Segura and François-André Danican Philidor. At that early date, no great corpus of chess knowledge had yet been amassed. It is for this reason that Greco's games should be understood as those of a brilliant inventor and pioneer rather than as guides to sound play.[15] They are also valuable examples of the Italian Romantic school of chess, in which development and material are eschewed in favour of aggressive attacks on the opponent's king. Greco paved the way for many of the attacking legends of the Romantic era, such as Philidor, Adolf Anderssen, and Paul Morphy.

Mikhail Botvinnik considered Greco to be the first professional chess player.[18] Other chess writers from the early period of modern chess had professional occupations, except Paolo Boi, who was wealthy through inheritance, and Giulio Cesare Polerio, who was a servant to a wealthy family. Greco, however, relied on chess to make a living.[19]

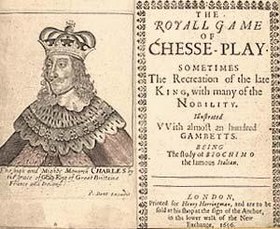

Greco's innovation to record entire games is perhaps his greatest legacy. Although his manuscripts were initially kept privately by his patrons, they would eventually become public; in 1656, years after his death, one of Greco's now-lost manuscripts was adapted as The Royall Game of Chesse-Play by Francis Beale in London.[20] Beale's book—and others like it—helped Greco's work reach a much larger audience than had his predecessors'.[4] In particular, Le Jeu Des Eschets, published in Paris 1669 became the principal source for the later English editions by William Lewis (1819) and Louis Hoffmann (1900).[21]

Games (as published by Beale) were not described in notation; rather, the movement of each piece was described in English, for example:

The Fooles Mate.

Black Kings Bishops pawne one house.

White Kings pawne one house.

Black kings knights pawne two houses

White Queen gives Mate at the contrary kings Rookes fourth house.

in which "house" refers to a square on the chessboard.[22]

In addition to the games ("Gambetts") listed in his manuals, Greco often gave general advice to his readers and an overview of the rules of chess ("The Lawes of Chesse"). These ranged from the familiar ("If you touch your man you must play it, and if you set it downe any where you must let it stand") to the obsolete ("If at first you misplace your men, and play two or three draughts, it lieth in your adversaries choice whether you shall play out the game or begin it again.").[23] Greco also describes the necessity of announcing check to one's opponent (still common in informal play but not in competition) and the disgrace of what he calls a "blind Mate" – a checkmate given but not noticed.[24]

The "Lawes of Chesse" were also not entirely standardized in Greco's time; for that reason, the rules as published by Beale would have been meant for a specific population. For example, Greco specifies that when castling in France, "the Rook... goeth into the Kings house".[24] In other countries the rules for castling were different. Modern castling, which Greco also describes, is sometimes called "alla Calabrese" in Greco's honour.[25]

Openings named for Greco

edit- Greco Defence: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 – A popular opening choice by novice players, it has also been used by players who, according to International Master Gary Lane, "should know better".[26] Also known as the McConnell Defense.[27]

- Greco Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 – An aggressive but rather dubious choice for Black which often leads to wild and tricky positions. FIDE Master Dennis Monokroussos even goes so far as to describe it as "possibly the worst opening in chess."[28] Also known as the Latvian Gambit.

- Calabrese Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 f5

- Bishop's Opening, Greco Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 Nf6 3.f4

- Giuoco Piano, Greco's Attack: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Nf6 5.d4 exd4 6.cxd4 Bb4+ 7.Nc3

- Giuoco Piano, Greco Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Nf6 5.d4 exd4 6.cxd4 Bb4+ 7.Nc3 Nxe4 8.0-0 Nxc3

- King's Gambit Accepted, Bishop's Gambit, Greco Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Bc4 Qh4+ 4.Kf1 Bc5

- King's Gambit Accepted, Greco Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 g5 4.Bc4 Bg7 5.h4 h6 6.d4 d6 7.Nc3 c6 8.hxg5 hxg5 9.Rxh8 Bxh8 10.Ne5

- Queen's Gambit Accepted, Central Variation, Greco Variation: 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.e4 b5[29]

Greco's mate

editGreco's mate is a checkmate pattern that occurs when a bishop (or queen) blocks the escape of a king on the back rank (or file), while a rook (or queen) delivers checkmate.[30]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Example games

editAs one of the players during the age of the Italian Romantic style, Greco studied the Italian game (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4), among other openings.[4] His games are regarded as classics of early chess literature and are sometimes still taught to beginners. Greco himself presented his games as between "White" and "Black";[9] the modern convention is to name the participants Greco and NN, for the Latin nomen nescio.

Among his games were the first smothered mate:

- NN vs. Greco, 1620

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.0-0 Nf6 5.Re1 0-0 6.c3 Qe7 7.d4 exd4 8.e5 Ng4 9.cxd4 Nxd4 10.Nxd4 Qh4 11.Nf3 Qxf2+ 12.Kh1 Qg1+ 13.Nxg1 Nf2# 0–1

and another that was continued into the endgame:

- Greco vs. NN, 1623[22]

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Qe7 5.0-0 d6 6.d4 Bb6 7.Bg5 f6 8.Bh4 g5 9.Nxg5 fxg5 10.Qh5+ Kf8 11.Bxg5 Qe8 12.Qf3+ Kg7 13.Bxg8 Kxg8 14.d5 Ne7 15.Bf6 Qf7 16.Nd2 h6 17.Bxh8 Qxf3 18.Nxf3 Kxh8 19.h3 Bd7 20.c4 Bd4 21.Nxd4 exd4 22.Rad1 c5 23.f4 Rf8 24.e5 dxe5 25.fxe5 Rxf1+ 26.Rxf1 Kg8 27.e6 Bc8 28.d6 Nc6 29.d7 Bxd7 30.exd7 d3 31.Re1 d2 32.Re8+ Kg7 33.d8=Q Nxd8 34.Rxd8 Kf7 35.Rxd2 1–0

Compositions

editAlthough Greco is known for recording entire games, he also included a number of chess problems in his manuscripts. Many of these were either copied directly, or adapted with modifications, from the works of previous authors.[17]

This puzzle uses the theme of the wrong rook pawn, and is probably an original composition by Greco:[31]

And here is one inspired by an earlier composition by Salvio:[33]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Quotes about Greco

edit- "Greco was the Morphy of the seventeenth century, and it may safely be said that in brilliancy and fertility of invention he has never been surpassed." (J.A. Leon, 1900)[35]

- "He [Greco] was the most productive and inventive chess author of the classical era." (Peter J. Monté, 2014)[36]

- "The games of Calabrisian Greco can be considered as a great education for beginners and intermediate players; even the most dedicated connoisseur of the board wants to find in its many unknown twists and elegant ways of playing, which enrich or round off his experiences." (translated from German, Max Lange)[37]

- "At the start of your career, you make a move against me, because of your proud step all my plans fail, as you approach I see all my defenses crumble, my champions fall while I resist in vain, my King Knight Rook and Queen don't measure up to your pawns." (translated from French, unknown)[20]

Manuscripts

editWhat follows is a list of manuscripts written by Greco, as given by Murray. There is a large amount of overlap among the contents of many of the works; many also have identical (or near-identical) titles. Efforts to list and date Greco's manuscripts have been made by Antonius van der Linde (1874), J. A. Leon (1900), Murray (1913), J. G. White (1919), Alessandro Sanvito (2005), and Peter J. Monté (2014).[10]

All Greco's manuscripts had Italian text, though some were given English titles. The title pages or first pages were the work of calligraphers, while the text was in Greco's own hand.[10] Furthermore, some works survive only as later copies or translations, and therefore only their translated titles are known.[38]

- Trattato del Gioco de Scacchi de Gioachino Greco Cusentino. Diuiso in Sbaratti & Partiti. (1620)

- Trattato del nobilissimo Gioco de Scacchi, il quale è rutratto di Guerra & di Ragion di Stato. Diuiso in Sbaratti, Partitti, & Gambetti, Giochi moderni, Con bellissimi Tratti occuli tutti diuersi. Di Gioacchino Greco Calabrese, L'Anno MDCXX. (1620)

- Untitled Manuscript (begins "Primo modo di gioachare a scachi", and is signed "gioachimo greco")

- Libretto di giochare a schachi composto da giochimo greco Calabrese di la tera di celico. Gioachino Greco practtica in Casa del Cardinal Saucelli, et Monsr. Boncompagno. (written before April 1621. Murray describes it as "splendidly executed"[12])

- Trattato del nobilissimo Gioco de Scacchi, il quale è rutratto di Guerra & di Ragion di Stato. Diuiso in Sbaratti, Partitti, & Gambetti, Giochi moderni, Con bellissimi Tratti occuli tutti diuersi. Di Gioacchino Greco Calabrese, L'Anno MDCXXI. (1621; survives as a French translation from 1622, and as copy made for Staunton in 1854)

- The Book of The ordinary games at Chestes. Composed by Joachnio Greco an Italian, Borne in Calabria: written for Nicholas Mountstephen dwellinge at Ludgate in London: Anno Domini 1623 (1623)

- The Book of The ordinary games at Chestes. Composed by Joachnio Greco an Italian, Borne in Calabria (undated; nearly identical to the previously listed manuscript)

- The Book of The ordinary games at Chestes. Composed by Joachnio Greco an Italian, Borne in Calabria (undated; omits some games by Ruy Lopez, that had been present in the previously listed manuscript)

- The Book of The ordinary games at Chestes. Composed by Joachnio Greco an Italian, Borne in Calabria: written for Nicholas Mountstephen dwellinge at Ludgate in Longon: Mount-Stephen 1623 (1623; includes games by Salvio)

- Trattato sopra la nobilta del Gioco di Scacchi dore in esso contiene en vero ritratto di Guerra et governo di stato diriso in sharatti et partiti et gambetti et giochi orinarii con tratti diversi belissimi, Composto per Gioacchino Greco Italiano Calavrese. (1624)

- Untitled Manuscript (1624)

- Trattato sopra la nobilta del Gioco di Scacchi dore in esso contiene en vero ritratto di Guerra et governo di stato diriso in sharatti et partiti et gambetti et giochi orinarii con tratti diversi belissimi, Composto per Gioacchino Greco Italiano Calavrese. (1625)

- Trattato del Nobilissimo et Militare Essercitio de Scacchi nel quale si contrengono molti bellissimi tratti et la vera Scienza di esso giocco. Somposto da Gioachino Greco Calabrese. (undated)

- Trattato del Nobilissimo et Militare Essercitio de Scacchi nel quale si contrengono molti bellissimi tratti et la vera Scienza di esso giocco. Sompoosto da Gioachino Greco Calabrese. (1625; a shortened text of the previous manuscript)

- Trattato del Nobilissimo et Militare Essercitio de Scacchi nel quale si contrengono molti bellissimi tratti et la vera Scienza di esso giocco. Sompoosto da Gioachino Greco Calabrese. (undated; with the same text of games as the previous manuscript)

- Il nobillissimo Gioco delli Scacchi. (undated)

- Le Ieu des Eschecs de Ioachim Grez Calabrois (1625; known from a 1660 French translation with the given title)

- Primo mode de Giuoco de partito composto per Gioachino Greco Calabrese (undated, contains problems only)

References

edit- ^ Beale 1656.

- ^ Murray 1913, p. 827.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1996, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d Murray 1913, p. 830.

- ^ a b c d Leon 1900, p. x.

- ^ Beale 1656, p. 1.

- ^ a b Monté 2014, p. 319.

- ^ Murray 1913.

- ^ a b Greco 1625.

- ^ a b c d e Monté 2014, p. 321.

- ^ von der Lasa 1859, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d Murray 1913, p. 828.

- ^ Leon 1900, p. ix.

- ^ a b von der Lasa 1859, p. 120.

- ^ a b Leon 1900, p. xii.

- ^ SBC 2013.

- ^ a b c Murray 1913, p. 829.

- ^ Gufeld & Stetsko 1996.

- ^ Monté 2014, p. 418.

- ^ a b Leon 1900, p. xvi.

- ^ Eales 1985, p. 98.

- ^ a b Beale 1656, p. 18.

- ^ Beale 1656, p. 15.

- ^ a b Beale 1656, p. 13.

- ^ Walker 1831, p. 6.

- ^ Lane 2001.

- ^ Benjamin & Schiller 1987.

- ^ Monokroussos 2007.

- ^ Hudson 2011.

- ^ Renaud & Kahn 1962, p. 75.

- ^ Monté 2014, p. 350.

- ^ Averbakh 1996.

- ^ Monté 2014, p. 350–51.

- ^ Syzygy.

- ^ Leon 1900, p. xiii.

- ^ Monté 2014, p. 354.

- ^ Leon 1900, p. xx.

- ^ Murray 1913, pp. 828–29.

Bibliography

- Averbakh, Yuri (1996). Chess Middlegames: Essential Knowledge. Cadogan. ISBN 1-85744-125-7.

- Beale, Francis (1656). The Royall Game of Chesse-Play, Sometimes the Recreation of the Late King, with Many of the Nobility. London.

- Benjamin, Joel; Schiller, Eric (1987). Unorthodox Openings. MacMillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-016590-0.

- C, Sarah Beth (July 2013). "Gioacchino Greco".

- de Man, Ronald; Guo, Bojun. "KQvKP Syzygy Endgame Tablebases".

- Eales, Richard (1985). Chess: The History of a Game. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-1195-8.

- Greco, Gioachino (1625). Trattato del Nobilissimo et Militare Essercitio de Scacchi nel Quale si Contengono Molti Bellissimi Tratti et la Vera Scienza di Esso Gioco. Sompoosto da Gioachino Greco Calabrese.

- Gufeld, Eduard; Stetsko, Oleg (1996). The Giuoco Piano. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-7802-0.

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1996) [First pub. 1992]. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280049-3.

- Hudson, Shane (January 2011). "scid.eco".

- Lane, Gary (2001). "Opening Lanes" (PDF).

- Leon, JA; Hoffman (1900). The Games of Greco. G Routledge.

- Monokroussos, Dennis (8 November 2007). "One Man's Trash is Another Man's Treasure".

- Monté, Peter J. (2014). The Classical Era of Modern Chess. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6688-7.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827403-3.

- Renaud, George; Kahn, Victor (1962) [1953]. The Art of Checkmate. Translated by Taylor, W.J. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

- von der Lasa, Baron (1859). Berliner Schacherinnerungen nebst den Spielen des Greco und Lucena. Veit & Comp.

- Walker, George (1831). A New Treatise on Chess. Sherwood, Gilbett and Piper.

External links

edit- Gioachino Greco player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- The Royall Game of Chesse Play, digitized at HathiTrust