Candombe is a style of music and dance that originated in Uruguay among the descendants of liberated African slaves. In 2009, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) inscribed candombe in its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[1]

| Candombe | |

|---|---|

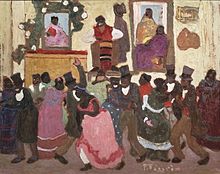

Painting of a crowd participating in a candombe | |

| Cultural origins | Bantu peoples |

| Typical instruments | Candombe drums |

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Candombe and its socio-cultural space: a community practice | |

|---|---|

| Country | Uruguay |

| Reference | 00182 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2009 (4th session) |

| List | Representative |

To a lesser extent, candombe is practiced in Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil. In Argentina, it can be found in Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Paraná, and Corrientes. In Paraguay, this tradition continues in Camba Cuá and in Fernando de la Mora near Asunción. In Brazil, candombe retains its religious character and can be found in the states of Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul.

This Uruguayan music style is based on three different drums: chico, repique, and piano drums. It is usually played in February during carnival in Montevideo at dance parades called llamadas and desfile inaugural del carnaval.

Origins

editCommon origins

editAccording to George Reid Andrews, a historian of black communities in Latin America, after the middle of the 19th century younger black people began to abandon the candombe in favor of practicing European dances such as the waltz, schottische, and mazurka.[2] Following this new twist, other Uruguayans began to imitate the steps and movements. Calling themselves Los Negros, upper class porteños in the 1860s and 1870s performed blackface and formed one of the carnival processions each year.

African-Uruguayans organized candombe dances every Sunday and on special holidays such as New Year's Eve, Christmas, Saint Baltasar, Rosary Virgin and Saint Benito. They would set a fire to heat the drums and play candombe music, especially during the night in certain neighborhoods such as Barrio Sur and Palermo in Montevideo.

The typical characters on the parade represent the old white masters during slavery in old Montevideo city. It was a mockery to their lifestyle with a rebel spirit for freedom and a way to remember the African origins.

In 1913, an anonymous dance historian identified only as "Viejo Tanguero" ("Old Tangoer") wrote about the 1877 creation of a dance referred to as a tango but featuring ideas from the candombe. This dance, which later became known as "soft tango," was created by African Argentines.[3][4][5][6]

Writing in 1883, dance scholar and folklorist Ventura Lynch described the influence of Afro-Argentine dancers on the compadritos ("tough guys") who apparently frequented Afro-Argentine dance venues. Lynch wrote, "the milonga is danced only by the compadritos of the city, who have created it as a mockery of the dances the blacks hold in their own places".[3] Lynch's report was interpreted by Robert Farris Thompson in Tango: The Art of Love as meaning that city compadritos danced milonga, not rural gauchos. Thompson notes that the population of city toughs dancing milonga would have included blacks and mulattoes, and that it would not have been danced as a mockery by all the dancers.[7]

In Argentina

editThe seeds of candombe originated in present-day Angola, where it was taken to South America during the 17th and 18th centuries by people who had been sold as slaves in the kingdom of Kongo, Anziqua, Nyong, Quang and others, mainly by Portuguese slave traders. The same cultural carriers of candombe colonized Brazil (especially in the area of Salvador de Bahia), Cuba, and the Río de la Plata with its capital Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The different histories and experiences in these regions branched out from the common origin, giving rise to different rhythms.[citation needed]

The African influence was not foreign to Argentina, where the candombe also has been developed with specific characteristics. A population of black African slaves had been present in Buenos Aires since around 1580. However, miscegenation with an increasingly white population (as Argentina received up to 6 million European immigrants) and structural racism (such as state-sponsored blanqueamiento policies) led to the progressive invisibilization of the Afro-Argentine population.[8][9]

In Buenos Aires, during the two governments of Juan Manuel de Rosas, it was common for “afroporteños” (black people of Buenos Aires) to perform candombe in public, even encouraged and visited by Rosas and his daughter, Manuela. Rosas was defeated at the battle of Caseros in 1852, and Buenos Aires began a profound and rapid cultural shift which saw a bigger emphasis on European culture. In this context, afroporteños replicated their ancestral cultural patterns increasingly into their private life. For this reason, onwards from 1862, the press, intellectuals and politicians began to assert the misconception of Afro-Argentine disappearance that has remained in the imagination of ordinary people from Argentina.[10]

Many researchers agree that the Candombe, through the development of the Milonga, is an essential component in the genesis of Argentine tango. This musical rhythm influenced, especially the "Sureña Milonga". In fact, tango, milonga and candombe form a musical triptych from the same African roots, but with different developments.[11]

Initially, the practice of Candombe was practiced exclusively by black people, who had designed special places called “Tangós”. This word originated sometime in the 19th century the word "Tango", but at that time not yet with its present meaning. Today, candombe is still practiced by Afro-Argentine and non-black populations across Argentina. In Corrientes Province, candombe is part of the religious feast of San Baltasar, a folk patron saint for Black Argentines.[12]

In Uruguay

editThe word candombe comes from a Kikongo word meaning "pertaining to blacks," and was originally used in Buenos Aires to refer to dancing societies formed by members of the African diaspora and their descendants. It came to refer to the dance style in general, and the term was adopted in Uruguay as well.[13] In Uruguay, candombe fused multiple African dance traditions into a complex choreography. Movements are energetic, and steps are improvised to suit.[14]

Present

editArgentina

editLately, some artists have incorporated this genre to their compositions, and have also created groups and NGOs of Afro-descendants, as the Misibamba Association, Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires Community. However, it is important to note that the Uruguayan Candombe is the most practiced in Argentina, both due to immigration from Uruguay and to the seductiveness of the rhythm that captivates the Argentines. For this reason they learn the music, dance and characters and recreate something similar. Uruguayan Candombe is played much in the neighborhoods of San Telmo, Montserrat and La Boca.

While the Argentine variety had less local diffusion (compared with the diffusion that occurred in Uruguay), mainly by the decrease of population of black African origin, its mixing with white immigrants and the prohibition of the carnival during the last dictatorship. The Afroargentine Candombe is only played by the Afro-Argentines in the privacy of their homes, mainly located in the outskirts of Buenos Aires.[15]

Recently, due to a change in strategy by the Afro-Argentines to move from concealment to visibility, there are increased efforts to perform it in public places, onstage and in street parades. Among the groups who play Afroargentine Candombe are: “Tambores del Litoral” (union of “Balikumba” from Santa Fe, and “Candombes del Litoral” from Parana, Entre Ríos), “Bakongo” (these, have their own web page), the “Comparsa Negros Argentinos” and "Grupo Bum Ke Bum (both from Asociación Misibamba). The latter two are in Gran Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires City and its surroundings).

Uruguay

editIn the late 1960s and early 1970s candombe was mixed with elements from 60s pop music and bossa nova to create a new genre called candombe beat. The origin of this genre was largely said to be the work of Eduardo Mateo, a Uruguayan singer, songwriter and musician together with other musicians such as Jorge Galemire.[16] This style was later adopted by Jaime Roos and also heavily influenced Jorge Drexler. Contemporary musicians like Diego Janssen and Miguel del Aguila are experimenting with fusing candombe with classical genres, jazz, blues and milonga.[17]

Instruments and musical features

editUruguayan candombe

editInscribed in 2009 on the Representative UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List, the candombe is a source of pride and a symbol of the identity of communities of African descent in Montevideo, embraced by younger generations and favouring group cohesion, while expressing the communities’ needs and feelings with regard to their ancestors.

The music of candombe is performed by a group of drummers called a cuerda. The barrel-shaped drums, or tamboriles, have specific names according to their size and function:

- chico, small, high timbre, serving as the rhythmic pendulum

- repique, medium, embellishes candombe's rhythm with improvised phrases

- piano, largest size, its function similar to that of the upright or electric bass

An even larger drum, called bajo or bombo (very large, very low timbre, accent on the fourth beat), was once common but is now declining in use. A cuerda at a minimum needs three drummers, one on each part. A full cuerda will have 50–100 drummers, commonly with rows of seven or five drummers, mixing the three types of drums. A typical row of five can be piano-chico-repique-chico-piano, with the row behind having repique-chico-piano-chico-repique and so on to the last row.

Tamboriles are made of wood with animal skins that are rope-tuned or fire-tuned minutes before the performance. They are worn at the waist with the aid of a shoulder strap called a talig or talí and played with one stick and one hand.

A key rhythmic figure in candombe is the clave (in 3–2 form). It is played on the side of the drum, a procedure known as "hacer madera" (literally, "making wood").

Master candombe drummers

editAmong the most important and traditional Montevidean rhythms are: Cuareim, Ansina and Cordon. There are several master drummers who have kept Candombe alive uninterrupted for two hundred years. Some of highlights are: in Ansina school: Wáshington Ocampo, Héctor Suárez, Pedro "Perico" Gularte, Eduardo "Cacho" Giménez, Julio Giménez, Raúl "Pocho" Magariños, Rubén Quirós, Alfredo Ferreira, "Tito" Gradín, Raúl "Maga" Magariños, Luis "Mocambo" Quirós, Fernando "Hurón" Silva, Eduardo "Malumba" Gimenez, Alvaro Salas, Daniel Gradín, Sergio Ortuño y José Luis Giménez.[18]

Argentine Candombe

editThe Afro-Argentine Candombe is played with two types of drums, played exclusively by men. Those drums are: “llamador” (also called "base", "tumba", "quinto" or "tumba base"), and "repicador" (also called "contestador", "repiqueteador" or "requinto"). The first is a bass drum, and the second is a sharp drum. There are two models of each of the drums: one made in hollowed trunk, and the other made with staves.

The first type are hung with a strap on the shoulder and are played in a street parade. The latter are higher than those, and played for granted. Both types of drums, are played only with both hands. Sometimes others drums are played: the "macú" and the "sopipa". Both are made from hollowed tree trunk, the first is performed lying on the floor, as it is the largest and deepest drum; and the "Sopipa" which is small and acute, is played hung on the shoulder or held between the knees.

Among the idiophones that always accompany the drums are the "taba" and "mazacalla", being able to add: the "quijada", the "quisanche", and the "chinesco”. The Argentine Candombe is a vocal-instrumental practice, all the same to be played sitting or street parade. There is a large repertoire of songs in African languages archaic, in Spanish or in a combination of both. They are usually structured in the form of dialogue and are interpreted solo, responsorial, antiphonal or in group. Although singing is usually a feminine practice, men may be involved. Where there is more than one voice, they are always in unison.

Uruguayan Candombe performance

editA full Candombe group, collectively known as a Comparsa Lubola (composed of blackened white people, traditionally with burnt corks) or Candombera (composed of black people), constitutes the cuerda, a group of female dancers known as mulatas, and several stock characters, each with their own specific dances. The stock characters include:

- La Mama Vieja: the Old Mother.

- El Gramillero: the Herb doctor. an ancient black man, dressed in top hat and frock coat, carrying a bag of herbs.

- El Escobero: the Broomsman, He has to be an expert candombero and graceful dancer, who performs extraordinary feats and of juggling and balance with his broom.

Candombe is performed regularly in the streets of old Montevideo's south neighbourhood in January and February, during Uruguay's Carnival period, and also in the rest of the country. All the comparsas, of which there are 80 or 90 in existence, participate in a massive Carnival parade called Las Llamadas ("calls") and vie with each other in official competitions in the Teatro de Verano theatre. During Las Llamadas, members of the comparsa often wear costumes that reflect the music's historical roots in the slave trade, such as sun hats and black face-paint. The monetary prizes are modest; more important aspects include enjoyment, the fostering of a sense of pride and the winning of respect from peers. Intense performances can cause damage to red blood cells, which manifests as rust-colored urine immediately after drumming.[19]

See also

editReferences

edit- Notes

- ^ "Candombe and Its Socio-Cultural Space: A Community Practice". UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ Andrews, 1979, p. 32

- ^ a b Collier et al., 1995. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Savigliano, Marta (2018-02-06). Tango And The Political Economy Of Passion. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-96555-5.

- ^ Nouzeilles, Gabriela; Montaldo, Graciela; Montaldo, Graciela R.; Kirk, Robin; Starn, Orin (2002-12-25). The Argentina Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2914-5.

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris (2006). Tango: The Art History of Love. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-9579-7.

- ^ Thompson, 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ "The return of "exiled" Candombe/ El regreso del Candombe desterrado". Archived from the original on 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ Reid Andrews, George. Los afroargentinos de Buenos Aires. Aquí mismo y hace tiempo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor. p. 41. ISBN 950-515-332-5.

- ^ Ocoró Luango, Anny (July 2010). "Los negros y negras en la Argentina: entre la barbarie, la exotización, la invisibilización y el racismo de Estado". La manzana de la discordia (in Spanish). 5 (2). Universidad del Valle: 48. ISSN 2500-6738. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Reid Andrews, George. Los afroargentinos de Buenos Aires. Aquí mismo y hace tiempo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor. p. 196. ISBN 950-515-332-5.

- ^ "Corrientes celebra a San Baltasar, el santo popular que hermana diferentes culturas". NEA Hoy (in Spanish). 6 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Thompson, 2005. pp. 96–97.

- ^ Collier et al, 1995. p. 43.

- ^ From the dream of a European Argentina, to the reality of American Argentina: the assumption of African ethno-cultural component and its (our) musical heritage/ Del sueño de la Argentina blancaeuropea a la realidad de la Argentina americana: la asunción del componente étnico-cultural afro y su (nuestro) patrimonio musical. Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mateo Alone Licks Himself Well". Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ^ "Raspa, pega y enciende - Brecha digital".

- ^ Candombe's repique/Luis Jure University School of Music , Montevideo Uruguay. Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tobal D, Olascoaga A, Moreira G, Kurdian M, Sanchez F, Rosello M, Alallon W, Martinez FG, Noboa O (2008). "Rust Urine after Intense Hand Drumming Is Caused by Extracorpuscular Hemolysis". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 3 (4): 1022–1027. doi:10.2215/cjn.04491007. PMC 2440284. PMID 18434617.

- Bibliography

- Andrews, George Reid (1919). Race versus Class Association: The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800–1900. Journal of Latin American Studies, May 1979, Vol. 11, No. 1.

- Collier, Cooper, Azzi and Martin (1995). Tango! The Dance, the Song, the Story. Thames and Hudson, Ltd. pages 44, 45. ISBN 978-0-500-01671-8

- Thompson, Robert Farris (2005). Tango The Art History of Love. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-40931-8

- Cirio, Norberto Pablo (2008). Ausente con aviso. ¿Qué es la música afroargentina?. In Federico Sammartino y Héctor Rubio (Eds.), Músicas populares : Aproximaciones teóricas, metodológicas y analíticas en la musicología argentina. Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, pages 81–134 and 249–277.

- Cirio, Norberto Pablo (2011). Hacia una definición de la cultura afroargentina. In Afrodescendencia. Aproximaciones contemporáneas de América Latina y el Caribe. México: ONU, pages 23–32. https://www.cinu.mx/AFRODESCENDENCIA.pdf Archived 2016-08-18 at the Wayback Machine.