Burnaby's Code or Laws, originally entitled Laws and Regulations for the better Government of his Majesty's Subjects in the Bay of Honduras, are an early written codification of the 17th and 18th century constitution and common law of the Baymen's settlement in the Bay of Honduras (later British Honduras). It was drafted by Sir William Burnaby or Joseph Maud, a Bayman, signed on 9 April 1765 at St. George's Caye, and subsequently confirmed by Sir William Lyttelton, governor of Jamaica.

| Burnaby's Code | |

|---|---|

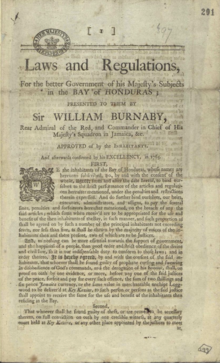

Laws and Regulations / first page of a 1765 transcript of Burnaby's Code at TNA / via AM | |

| Created | 9 April 1765 |

| Location | not extant; transcripts published |

| Author(s) |

|

| Signatories | 85 Baymen, inc. 2 women |

| Purpose | Constitution |

History

editPrelude

editDistant

editThe unwritten constitution and common law of the Baymen's settlement is commonly traced back to the introduction of buccaneering custom, upon the 1638 landing of a group of shipwrecked English buccaneers at the mouth of the Old River.[1][2][3][4] Said constitution and common law eventually came to be known as 'the old custom of the Bay,' or 'Jamaica discipline.'[5] It is often thought to have persisted largely unchanged throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries.[6] It is now commonly contrasted with the contemporary constitution and common law of royal and chartered colonies in the West Indies and America, which are thought to have afforded settlers less or much less say in legislative, judicial, and executive matters.[7][8][9][10][note 1][note 2][note 3]

Immediate

editA Spanish armadilla, under orders from the Governor of Yucatán, struck the English logging settlement in the Bay of Honduras on Christmas Day in 1759. Baymen were completely routed, and shortly evacuated the settlement, taking refuge in Mosquito Shore.[6] Upon learning of their restoration via the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the exiled Baymen once again returned to the settlement, landing at the mouth of the Old River aboard five ships sometime in April 1763.[11][12][13][14]

On 23 December 1763, Ramírez de Estenoz,

[G]overnor of Yucatan and the commandant of Baccalar, interrupted their [Baymen's] trade in general, by requiring them to produce a regular licence, either from their own sovereign, or from the king of Spain. This interruption was followed by the expulsion of the settlers from those points of the coast which were considered as beyond the limits assigned in the recent treaty [of Paris 1763]. They were commanded to retire from Rio Hondo within the space of two months [by 28 February 1764]; they were confined to the south bank of Rio Nuevo; and both at Rio Nuevo and Rio Wallis, they were restricted from ascending to the distance of more than twenty leagues from the sea. By these aggressions, more than five hundred settlers were driven from their habitations, with the loss of their property, amounting to above £27,000 sterling.

— A British settler [Bayman], undated.[15]

The Baymen, deeming Estenoz's actions a treaty violation, shortly petitioned the Governor of Jamaica and HM Government for redress, further publicising the affair in the press.[16][17] On 8 February 1765, HMS Wolf, Hay captain, arrived at the settlement, under instructions 'for the Re-establishment of all the Baymen at their old Works in any Part of the Bay of Honduras, the most convenient for the cutting [of] Logwood.'[18][19]

Baymen were fully restored to their works during 5–26 March 1765, upon the arrival of William Burnaby, admiral, aboard HMS Dreadnought or HMS Active.[20][21][17]

Creation

editBurnaby's Code is thought to have been drafted during March 1765, or during the first week of April 1765. Details of its creation are uncertain, though it is commonly thought to have involved little deviation from the custom of the Bay, being rather a written, explicit record of the settlement's 17th and 18th century constitution and common law. Authorship is commonly ascribed to William Burnaby, or to Joseph Maud. It was signed on 9 April 1765, most likely at St. George's Caye, by 85 Baymen, including two women and some unpropertied men.[note 4]

When Sir William Burnaby came down to the Bay to settle the differences with the Spaniards, it was thought proper to establish some form of government amongst the Inhabitants. The little time Mr. Maud had resided amongst them afforded an opportunity of discovering their temper and disposition, from whence he took occasion to draw a set of laws and regulations for their future welfare and happiness, which were not only agreed to by the inhabitants, in presence of the admiral, at a meeting held on Key Kazine, for that purpose, but afterwards approved of by his Excellency William Henry Littleton, Esq; governor of Jamaica; and whoever will take the trouble of perusing those laws and regulations, will perceive that they are founded upon principles which do credit to the author, and must transmit his name with honour to posterity.

Aftermath

editThe Public Meeting met on 10 April 1765.[24] Burnaby departed in late April 1764. Quarterly court was held on 30 May 1765. The Code was published in late 1765, and re-printed in 1809, as part of a digest of laws laid before the Public Meeting.[25]

Content

editPreamble

editTwo paragraphs constitute the Code's preamble. The first part begins–[note 6]

WE the inhabitants of the Bay of Honduras, whose names are hereunto subscribed, do, by and with the consent of the whole, agree, from and after the date hereof, to bind ourselves to the strict performance of the Articles and Regulations hereafter mentioned, [...]

— First part of preamble.

The first part further–

- binds the Baymen and their 'heirs, executors, and administrators, and assigns' to the Code's rules and regulations,

- stipulates that sums received for breaches of these rules 'are to be appropriated for the use and benefit of the then inhabitants of the Bay,' and

- fixes the number of Magistrates to five, six, or seven (including at least two Justices of the Peace), all of whom 'shall be chosen by the majority of voices of the inhabitants then and there present.'

The second part introduces the articles, emphasising the first point aforementioned.

And as nothing can be more essential towards the support of government and the inhabitants' happiness than good order and strict obedience to the divine and civil law; so it is our indispensable duty to conform to those laws, and in order thereto,

— Second part of preamble.

Articles

editThe Code contains twelve articles.[note 7]

First

editOn blasphemy

The first article is enacted 'by and with the consent of the said inhabitants.' It prohibits 'profane cursing and swearing, in disobedience of God's commands, and the derogation of his honour,' making this a summary offence (subject to conviction by one JP) for which offenders would forfeit 'two shillings and sixpence, Jamaica currency, or the same value in merchantable unchipt logwood.'

Second

editOn theft

The second article lacks an authorising clause. It prohibits theft and the aiding or abetting of it, making this a non-summary offence (triable by a quarterly court) for which offenders would be 'obliged to make restitution for the full value of the goods or effects so stolen, but be further subject to such other punishment and penalty as the said court shall adjudge.'

Third

editOn inveigling crewmen

The third article lacks an authorising phrase. It prohibits inveigling sailors or crewmen, and harbouring, entertaining, employing, or concealing them without their shipmaster's written licence. Offenders would forfeit twenty tonnes of merchantable unchipped logwood, with the runaway sailor subject to summary conviction by a JP 'to be dealth with and punished as the said Justice shall judge his crime to deserve.'

Fourth

editOn labour contracts

The fourth article is enacted 'for the better government of the said inhabitants, and in order to prevent as much as possible any disputes or disturbances which may arise therefrom.' It prohibits labour or service contracts by parole, requiring these to be in writing, and to state the agreed upon salary or wage, and 'where and in what manner it [salary or wage] is to be paid.' No penalty or punishment for breaches is mentioned.

Fifth

editOn impressment

The fifth article lacks an authorising phrase. It prohibits impressment by parole, allowing only voluntary (non-impressed), written service contracts (as per the fourth article). The impressment of steersmen, for a single trip, is, however, exempted from the article. Breaches are made summary offences, with convictions subject to a penalty of ten tonnes of merchantable unchipped logwood, which are 'to be distributed agreeably to the tenor of these Articles.'

Sixth

editOn taxation

The sixth clause lacks an authorising phrase. It authorises taxation in the following manner.

- The Public Meeting would appoint a committee of two JPs and five principal inhabitants to determine which taxes were 'necessary to be laid on the inhabitants of the Bay, for the use and benefit of the said inhabitants and settlers.'

- The tax committee would impose and collect taxes 'by the authority aforesaid [i.e. of the Public Meeting].'

The article further penalises defaults or non-payment with a fine of ten tonnes merchantable, unchipped logwood. Furthermore, default or non-payment of said fine is penalised by the offending party's being 'excluded the benefit of any advantage arising from the fines and forfeitures herein beforementioned, and intended for the uses and benefit of the said inhabitants.'

Seventh

editOn quarterly courts

The seventh article is enacted 'In order for the better putting in execution the Articles and Regulations herein mentioned, and for the better government of the said inhabitants residing in the Bay.' It constitutes quarterly courts as follows.

- The courts are to 'try and determine any disputes which may arise among the inhabitants of the Bay.'

- Seven justices, appointed by Public Meeting, are to preside 'with the full power and authority from us [the inhabitants].'[note 8]

- Sessions are to be held every three months at St. George's Caye.

- Trials are to be by 'a jury of thirteen good and lawful subjects, housekeepers of the Bay, [to] be chosen by the majority of the voices of the inhabitants of the Bay, then and there present.'

- The courts' determinations are to be final.

The articles further penalises non-compliance with the courts' sentences by forfeiture of property 'wheresoever it is to be found, of any kind whatsoever.'

Eighth

editOn naval officers

The eighth article is enacted 'by and with the consent of the inhabitants of the Bay.' It vests Royal Navy officers with 'full power' to 'execute and enforce' the inhabitants' laws and agreements, and JPs' or courts' sentences, further requesting that officers exercise said authority.

Ninth

editOn ad hoc courts

The ninth article is enacted 'by and with the consent of the inhabitants of the Bay.' It provides for the settling of 'disputes which may hereafter arise amongst the inhabitants of the Bay, not mentioned in these Regulations.' These are to be referred to an ad hoc court of two JPs and five principal inhabitants, whose determination is to be final. Of the five principal inhabitants, one is to be chosen by the JPs, and four by the parties in dispute.

Tenth

editOn offences not explicitly treated

The tenth article has no enacting clause. It provides for all crimes and misdemeanours not mentioned in the Code. These are to 'be punished according to the custom of the Bay in like cases.'

Eleventh

editOn legislation

The eleventh article is enacted 'for the better government of the inhabitants of the Bay, [...] by and with the consent of the whole of the inhabitants.' It binds inhabitants to 'all such laws and regulations as shall hereafter be made by the Justices of the Bay in full council; those laws and regulations being first approved of by the majority of the inhabitants of the Bay,' and to any fines, penalties, or forfeitures as imposed in said laws and regulations.

Twelfth

editOn seizures upon a debtor's default

The twelfth article is enacted 'by and with the consent of the inhabitants of the Bay.' It prohibits creditors' seizure of a debtors' property (in case of default) without prior authority from the Justices of the Bay. Breaches are penalised by forfeiture of the debt, and further punishment 'as the Justice shall judge the party offending to deserve, agreeably to the tenor of these regulations.'

Signatures

editThe Code closes as follows.[note 9]

| Given under our hands and seals at this ninth day of April, one thousand seven hundred and sixty five. | |

| John Lawrie | James Farrell |

| John Maud | D. Fitz Gibbon |

| Basil Jones | Henry Jones |

| John Douglas | Ralph Wildridge |

| Christpher Sinnett | John Smith |

| Thomas Coake | John Potts |

| John Care | John Cathcart |

| John Gordon | Maurice O'Brien |

| Charles Golding | [ill] [ill]err |

| John Furnall | John Mc. Target |

| William Ryder | William Weston |

| Thomas Remington | William Thox |

| Thomas Yoemans | Owen Thom |

| William Eardly | Ebenezer Tyler |

| William Car | Thomas Barra |

| Edward Kirk | John Howa |

| Thomas Bates | Bryan Cumberland |

| William Galaspy | John Gardner |

| Michael Elsters | Thomas Evans |

| William Tucker | Mary Wel |

| Robert Montgommery | [ill] [ill]le |

| Rorolf Henrikson | [ill] [ill]nder |

| Rodolphus Green | [ill]dby Pinder |

| Alexander Douglas | William O'Brien |

| William Cox | Nicholas Green |

| John Swain | Bartholomew Alex. Pitt |

| Thomas Catts | Richard Armstrong |

| John Oliver | William Shade |

| Michael Patterson | Nehemiah Gale |

| Joseph Gaddes | Charles Keeling |

| William Oxford | Alexander Lindsay |

| Michael Roberts | George Jeffreys |

| John Hamilton | John Cook |

| Samuel Griffiths | James Smith |

| Nathaniel Parent | Francis Hickey |

| Ralph Wild | William Wyatt |

| William Dal | James Grant |

| William Dunn | Andrew Slumen |

| George Ceau | Benjamin Bascome |

| John Per | Thomas Potts |

| Thomas Roblie | Richd. Fran. O'Brien |

| Mary Allen | and |

| William Rumbol | John Garbutt |

Analysis

editThe code is commonly thought to have codified the settlement's pre-existing or prevailing legal customs, though it has been further suggested that Royal Navy rules and regulations partially influenced its content.[26][note 10]

Legacy

edit[W]hoever will take the trouble of perusing those laws and regulations [Burnaby's Code], will perceive that they are founded upon principles which do credit to the author [Joseph Maud], and must transmit his name with honour to posterity.

Burnaby has been credited with having 'put the settlement on a most respectable footing.'[27] His lieutenant, who had been despatched to the Governor of Yucatán, in Mérida, published an account of the voyage in 1769.[28]

Burnaby's Code came to be 'celebrated' by Baymen and later British Hondurans as their 'charter of liberty.'[29][30][31][10] It is commonly considered Belize's first written constitution, and has been deemed the first such to be signed by women.[32][33][34][35][36][37][note 11] Scholarly opinion on Burnaby's Code is divided, with some deeming it insignificant, and others opining otherwise.[38][note 12]

Notes

edit- ^ For instance, the Public Meeting, constituted by all free, male property-holders (coloured and white), held legislative and final judicial authority. A varying number of Magistrates, annually elected by free, male property-holders (coloured and white), held executive and original or summary judicial authority (Soriano 2020, pp. 76–77). HM Government and the Governor of Jamaica held final legislative, judicial, and executive authority, as delegated by the Crown, but rarely exercised it (Soriano 2020, pp. 63–64).

- ^ The settlement's odd constitution and common law have been attributed to its peripheral status within the British Empire, and further likened to that of Newfoundland (Soriano 2020, pp. 61, 86).

- ^ Upon the resettling of Rattan on 23 August 1742, the Public Meeting petitioned HM Government for the appointment of a Governor and a resident detachment of the British Army. Consequently, a 14 June 1744 Order-in-Council granted the latter request, but not the former, further–

- instructing Baymen to appoint amongst themselves twelve 'of their principle settlers' to form a council under the supervision of the governor (Soriano 2020, p. 64),

- requiring the settlement's bye-laws [rules and regulations] to be 'agreeable to the Laws of England, and subject to His Majesty's approbation or disallowance for the establishing [of] peace, policy and good order in the Colony, but the said By-Laws should be of no force until the Governor shall have separately given his assent to them' (Soriano 2020, p. 64),

- empowering the Governor and Council 'to decide in all cases Civil and Criminal in a summary way, but agreeable to the laws of Great Britain' (Soriano 2020, p. 64).

- ^ BNL 1771, p. 1 of supplement, NYG 1771, p. 3, obituaries of Joseph Maud, attribute authorship to the same. Soriano 2020, p. 66 attributes authorship to Burnaby. Many simply credit the Code to its namesake, without explicit mention of its drafter (eg Henderson 1809, pp. 62–63, Bystrova 2015, p. 314).

- ^ Contemporary press reported the event as follows.

The Brig Chance, Capt. Fairchild, arrived here [New York City] on Friday last [17 May] in 32 Days from the Bay of Honduras [left 15 April].— He informs [that Burnaby, having arrived,] immediately issued Regulations for the better Government of His Majesty's Subjects in the Bay of Honduras; [...] and got the Inhabitants so to associate and meet together as to fix and appoint proper Persons for the holding Courts of Justice quarterly, with the Assistance of a Jury, to try and determine all Disputes whatsoever, which Determinations are to be enforced by the Commanding Officer for the Time being of any of His Majesty's Ships of War which may be sent thither. The persons chosen to the Justiciary and confirmed by the Admiral were, Messrs. John Laurie, Basib Jones, James Farrell, John Douglas, Joseph Maud, David Fitz Gibbon, and Chrisopher Sinnet.

— Editors, New-York Gazette, 20 May 1765 (NYG 1765, p. 2). - ^ All content from published transcripts of the Code (eg Burdon 1931, pp. 99–106, Hunt 1809, pp. 7–18, SGC 2014, first to last para).

- ^ All content from published transcripts of the Code (eg Burdon 1931, pp. 99–106, Hunt 1809, pp. 7–18, SGC 2014, first to last para).

- ^ The seven justices appointed were Joseph Maud, John Lawrie, James Ferrell, David FitzGibbon, Basil Jones, John Douglas, and Christpher Sinnet.

- ^ All content from published transcripts of the Code (eg Burdon 1931, pp. 99–106, Hunt 1809, pp. 7–18, SGC 2014, first to last para).

- ^ In particular, the first, eighth, and tenth articles [on blasphemy, on naval officers, on offences not explicitly treated, respectively] have been likened to Royal Navy rules and instructions for personnel at sea (Soriano 2020, pp. 67–69).

- ^ The settlement's laws and regulations were first compiled by William Hunt during 1806–1808, upon a 12 April 1806 commission from the Magistrates (BI 1888, p. 1). Hunt's digest included laws and regulations passed during 9 April 1765 – 28 June 1808 (BI 1888, p. 1). It was published in 1809, with Hunt retaining copyright to 1811 (BI 1888, p. 1, Hunt 1809, title page and p. 5). The commission's centennial was commemorated with a retrospective by the Colonial Guardian in 1906 (in CG 1906a through CG 1906h).

- ^ It has been recently argued 'that Burnaby's Code should be viewed as a crucial legal document in establishing the roots of British Hondruas, and later Belizean, legal practices' (Soriano 2020, p. 59, first paragraph ie abstract). Works dismissive of the Code include Dobson 1973, p. 88, Bolland 2009, p. 48. Works not dismissive of it include Bystrova 2015, p. 314.

Citations

edit- ^ Soriano 2020, pp. 62, 86.

- ^ Bolland 1973, p. 4.

- ^ Bridges 1828, pp. 134–136.

- ^ Tilby 1912, pp. 9–10, 12–13.

- ^ Soriano 2020, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b BI 1888, p. 1, fourth para.

- ^ Soriano 2020, pp. 61–62, 86.

- ^ Bolland 1973, pp. 1–2, 21.

- ^ Humphreys 1961, p. 6.

- ^ a b CP 1880, p. 86.

- ^ Bolland 1973, p. 7.

- ^ Bridges 1828, p. 147.

- ^ Tilby 1912, p. 11.

- ^ Calderón Quijano 1944, pp. 193, 200.

- ^ Coxe 1815, p. 316.

- ^ Soriano 2020, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Beatson 1804, pp. 9–10.

- ^ NYM 1765a, p. 3.

- ^ GG 1765a, p. 2.

- ^ RM 1765, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Breen 2008, fifth para.

- ^ a b NYG 1771, p. 3.

- ^ a b BNL 1771, p. 1 of supplement.

- ^ Bolland 1973, p. 9.

- ^ BI 1888, p. 1.

- ^ Soriano 2020, p. 59.

- ^ Beatson 1804, p. 10.

- ^ Cook 1769, title page.

- ^ Tilby 1912, pp. 12–13.

- ^ BA 1881, p. 3.

- ^ CG 1888, p. 2.

- ^ A 2008, first para.

- ^ A 2009, fifteenth para.

- ^ CF 2007, eleventh and twelfth paras.

- ^ HT 2000, fourth and fifth paras.

- ^ SGC 2014, subtitle or tagline.

- ^ Morris et al. 2010, p. 264.

- ^ Soriano 2020, pp. 59, 66.

References

editCode

edit- "Burnaby's Code". Ambergris Caye Belize Message Board. 1765. Retrieved 5 June 2022. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Burnaby's Code". Village Council of St. George's Caye. 1765. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Scholarship

edit- anon. (1857). The laws of the settlement of British Honduras in force in the twentieth year of the reign of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria. Belize: John McKinley Daley. OCLC 45638792.

- Beatson, Robert, ed. (1804) [1790]. Volume the fourth. Naval and military memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orm, No. 39 Paternoster-Row; W. J. and J. Richardson, Royal Exchange; A. Constable and Co.. Edinburgh; and A. Brown, Aberdeen. OCLC 4643956.

- Bolland, O. Nigel (1973). "The social structure and social relations of the Settlement in the Bay of Honduras (Belize) in the 18th century". Journal of Caribbean History. 6 (sn): 1–42. ISSN 0047-2263.

- Bolland, O. Nigel (2009) [1988]. Colonialism and Resistance in Belize : Essays in Historical Sociology (5th ed.). Benque Viejo: Cubola. OCLC 720335204.

- Breen, Kenneth (2008). "Burnaby, Sir William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64850. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bridges, George, ed. (1828). Volume the second. Annals of Jamaica. Vol. 2. London: John Murray. OCLC 4612281.

- Burdon, John, ed. (1931). From the earliest date to A. D. 1800. Archives of British Honduras. Vol. 1. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. OCLC 3046003.

- Bystrova, Kate, ed. (2015). For 2015. The Commonwealth Yearbook. London: Published for the Commonwealth Secretariat by Nexus Strategic Partnerships. OCLC 1166715355.

- Cal, Angel (1991). Rural society and economic development: British mercantile capital in nineteenth-century Belize (PhD). University of Arizona. ProQuest 303947249.

- Calderón Quijano, José Antonio (1944). Belice, 1663(?)-1821 : historia de los establecimientos británicos del Río Valis hasta la independencia de Hispano-américa. Publicaciones de la Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos de la Universidad de Sevilla ; no. general 5 ; serie 2a ; monografías ; no. 1. Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos. OCLC 2481064.

- Camille, Michael (1994). Government initiative and resource exploitation in Belize (PhD). Texas A&M University. ProQuest 304153638.

- Campbell, Mavis (2003). "St George's Cay: Genesis of the British Settlement of Belize -- Anglo-Spanish Rivalry". Journal of Caribbean History. 37 (2): 171–203. ISSN 0047-2263.

- Clark, Charles (1834). A summary of colonial law, the practice of the Court of appeals from the plantations, and of the laws and their administration in all the colonies : with charters of justice, orders in Council, &c. ... London: S. Sweet, 3, Chancery Lane; A. Maxwell, 32, and Stevens & Sons, 39, Ball Yard; Law Booksellers & Publishers: R. Milliken and Son, Grafton St. OCLC 30148926.

- Cook, James (1769). Remarks on a passage from the River Balise, in the Bay of Honduras, to Merida; the Capital of the Province of jucatan, In the Spanish West Indies. By Lieutenant Cook, Ordered by Sir William Burnaby, Rear Admiral of the Red, in Jamaica; With Dispatches to the Governor of the Province; Relative to the Logwood Cutters in the Bay of honduras, In February and March 1765. London: Printed for C. Parker, the Upper Part of New Bond Street. OCLC 2478951.

- Coxe, William, ed. (1815) [1813]. Volume the fourth. Memoirs of the kings of Spain of the House of Bourbon, from the accession of Philip V. to the death of Charles III, 1700 to 1788, Drawn from the original and unpublished documents. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, Paternoster-Row. OCLC 2544832.

- Curry, Herbert (1957). "British Honduras: From Public Meeting to Crown Colony". Americas. 13 (1): 31–42. doi:10.2307/979212. JSTOR 979212. S2CID 143843148.

- Dobson, Narda (1973). A History of Belize. London, New York, Port of Spain & St. Andrew: Longman Caribbean. OCLC 795980.

- Dupont, Jerry (2001). The common law abroad : constitutional and legal legacy of the British empire. Littleton, Colo.: Fred B. Rothman. OCLC 44016553.

- Finamore, Daniel (1994). Sailors and slaves on the wood-cutting frontier: Archaeology of the British Bay Settlement, Belize (PhD). Boston University. ProQuest 304114781.

- Henderson, George (1809). An account of the British settlement of Honduras; being a view of its commercial and agricultural resources, soil, climate, natural history, &c. London: Printed by and for C. and R. Baldwin, New Bridge-Street. hdl:2027/uc1.31175035187452.

- Henderson, George (1811) [1809]. An account of the British settlement of Honduras; being a view of its commercial and agricultural resources, soil, climate, natural history, &c. London: Printed for R. Baldwin, Paternoster Row.

- Humphreys, Robert (1961). The diplomatic history of British Honduras, 1638-1901. London & New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 484695.

- Hunt, William, ed. (1809). Regulations for the better government of His Majesty's subjects in the Bay of Honduras : presented to them by the honourable William Burnaby, knight, rear-admiral of the red, and commander in chief of His Majesty's squadron in Jamaica. London: Printed by T. Gillet, Crown-Court, Fleet-Street. hdl:2027/nnc1.cu54219256. OCLC 84067060.

- Jarvis, Michael (2012). In the eye of all trade : Bermuda, Bermudians, and the maritime Atlantic world, 1680-1783. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 861793496.

- Judd, Karen (1992). Elite reproduction and ethnic identity in Belize (PhD). City University of New York. ProQuest 304022149.

- Lewinski, Wilhelm (1961). "DAS STREITOBJEKT BRITISCH-HONDURAS UND DIE KARIBISCHE FÖDERATION". Zeitschrift für Politik. Neue Folge. 8 (1): 63–71. JSTOR 24225114.

- Mills, Arthur (1856). Colonial Constitutions: An Outline of the Constitutional History and Existing Government of the British Dependencies. London: John Murray.

- Mohamed, Saira (2007). "The United Nations Declaration on the RIGHTS of Indigenous Peoples and Cal v. Attorney General, Supreme Court of Belize". International Legal Materials. 46 (6): 1008–1049. doi:10.1017/S0020782900032253. S2CID 232252231.

- Morris, John; Jones, Sherilyn; Awe, Jaime; Thompson, George; Badillo, Melissa, eds. (2010). Archaeological Investigations in the Eastern Maya Lowlands : Papers of the 2009 Belize Archaeology Symposium. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology. Vol. 7. Belmopan: Institute of Archaeology. OCLC 714903259.

- Rogers, E. (1885). "British Honduras: Its Resources and Development". Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society. 1 (7): 197–227. JSTOR 60229682.

- Ryan, Thomas (1976). Party politics in Belize (MA). University of Nebraska at Omaha. ProQuest 1698247563.

- Smith, William, ed. (1852). Vol. II. The Grenville papers : being the correspondence of Richard Grenville, Earl Temple, K.G., and the Right Hon. George Grenville, their friends and contemporaries. Vol. 2. London: John Murray. OCLC 3838894.

- Soriano, Tim (2020). "'The peculiar circumstances of that settlement': Burnaby's code and Royal Naval rule in British Honduras". Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Law and History Society. 7 (1): 59–88. ISSN 2207-4325.

- Tilby, A. Wyatt (1912). Britain in the tropics, 1527-1910. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 2795822.

- Wainwright, Joel (2020). "The Colonial Origins of the State in Southern Belize". Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos. 46 (1): 1–22. doi:10.15517/aeca.v46i0.45072. S2CID 146501060.

Other

edit- A (10 July 2008). "The mulattos". Amandala.

- A (4 September 2009). "St. George's Caye declared National Historical Landmark". Amandala. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.

- A (28 August 2019). "The Reef Afire – a book review". Amandala. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.

- BA (1 October 1881). "What they say in England". Belize Advertiser. Vol. I, no. 20. p. 3.

- BH (2021). "A Brief History of the Legislature of Belize". Belize Hub. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.

- BI (22 November 1888). "REPORT on the Revision and Consolidation of the LAWS of British Honduras, with a brief historical restrospect, by W. Meigh Goodman, Chief Justice of the colony and Commissioner to revise and Consolidate its Laws". Belize Independent. No. 7. p. 1.

- BNL (11 July 1771). "New-York, July 1". Boston News-Letter. No. 3535. p. 1 of supplement.

- BTB (2007). "National Tour Guide Training Program" (PDF). Belize Tourism Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2022.

- CF (24 January 2007). "Cayo student tops social studies quiz". News 5. Great Belize Productions. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.

- CG (8 December 1888). "Ye Buryal of ye maist honorable & Worshypful Knyght, ...". Colonial Guardian. Vol. VII, no. 49. p. 2.

- CG (7 April 1906a). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 14. p. 2.

- CG (21 April 1906b). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 16. p. 3.

- CG (5 May 1906c). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 18. p. 3.

- CG (19 May 1906d). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 20. p. 3.

- CG (26 May 1906e). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 21. p. 3.

- CG (2 June 1906f). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 22. p. 3.

- CG (7 July 1906g). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 27. p. 3.

- CG (1 September 1906h). "Burnaby's Laws". Colonial Guardian. Vol. XXV, no. 35. p. 4.

- CP (1880). Papers relating to H.M. Colonial Possessions, 1877-79. Command Papers no. C.2598. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - HCP (1829). Coms. of Inquiry into Administration of Criminal and Civil Justice in W. Indies and S. American Colonies: Third Report (Honduras and Bahamas). House of Commons Papers no. 334. London.

- GG (16 May 1765a). "Charlestown, South-Carolina, May 8". Georgia Gazette. No. 111. p. 2.

- GG (19 September 1765b). "Savannah, September 19". Georgia Gazette. No. 129. p. 2.

- HT (2000). "Letters". Hart Tillett. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.

- JHC (1803). From May the 10th, 1768, in the Eight Year of the Reign of King George the Third, to September the 25th, 1770, in the Tenth Year of the Reign of King George the Third. Journals of the House of Commons. Vol. 32. London: Re-printed by Order of the House of Commons.

- NYG (20 May 1765). "New-York, May 20". New-York Gazette. No. 337. p. 2.

- NYG (1 July 1771). "New-York, July 1". New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. No. 1027. p. 3.

- NYM (8 April 1765a). "New-York, April 8". New-York Mercury. No. 702. p. 3.

- NYM (19 August 1765b). "Just Published, Laws and regulations, ...". New-York Mercury. No. 721. p. 3.

- RM (June 1765). "St. James's, June 15, 1765". Royal Magazine or Gentleman's Monthly Companion. Vol. 12, no. sn. pp. 330–331.

- SGC (2014). "Burnaby's Code". St. George's Caye. Village Council of St. George's Caye. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022.