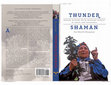

Books by Ana Mariella Bacigalupo

https://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/books/bacigalupo-thunder-shaman

As a “wild,” drumming thunde... more https://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/books/bacigalupo-thunder-shaman

As a “wild,” drumming thunder shaman, a warrior mounted on her spirit horse, Francisca Kolipi’s spirit traveled to other historical times and places, gaining the power and knowledge to conduct spiritual warfare against her community’s enemies, including forestry companies and settlers. As a “civilized” shaman, Francisca narrated the Mapuche people’s attachment to their local sacred landscapes, which are themselves imbued with shamanic power, and constructed nonlinear histories of intra- and interethnic relations that created a moral order in which Mapuche become history’s spiritual victors. Thunder Shaman represents an extraordinary collaboration between Francisca Kolipi and anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, who became Kolipi’s “granddaughter,” trusted helper, and agent in a mission of historical (re)construction and myth-making. The book describes Francisca’s life, death, and expected rebirth, and shows how she remade history through multitemporal dreams, visions, and spirit possession, drawing on ancestral beings and forest spirits as historical agents to obliterate state ideologies and the colonialist usurpation of indigenous lands. Both an academic text and a powerful ritual object intended to be an agent in shamanic history, Thunder Shaman functions simultaneously as a shamanic “bible,” embodying Francisca’s power, will, and spirit long after her death in 1996, and an insightful study of shamanic historical consciousness, in which biography, spirituality, politics, ecology, and the past, present, and future are inextricably linked. It demonstrates how shamans are constituted by historical-political and ecological events, while they also actively create history itself through shamanic imaginaries and narrative forms.

https://www.utexas.edu/utpress/books/bacsha.html

“The book argues that the bodies of machi shaman... more https://www.utexas.edu/utpress/books/bacsha.html

“The book argues that the bodies of machi shamans, their desires and gendered performances, and their possession by and control over spirits become sites for local conflicts and expressions of identity and difference between Mapuche and non-Mapuche people-the places where power, hierarchy and healing are played out. This is a complex and demanding menu. It assumes deep and intimate ethnographic knowledge of her subject, a subtle sense of Chilean history, and agility with theories of gender, performance, and ritual, a tough project but she brings it off. The book comes come in a brilliant final chapter where Bacigalupo and her informants debate her mention of “witchcraft” and “homosexuality,” foregrounding the difficulty of generalizing between machi and the stakes of different machi in presenting themselves and being represented by clients, anthropologists, the Chilean nation, and a New-Age Audience.”

“This is a significant contribution to the field, first as a detailed and complex presentation of machi shamans and as a challenging confrontation of any simple generalization about gender and spirit possession. As a work of ethnography, it sets a high standard for both depth of on the ground knowledge of machi lives, and for its ability to relate those lives to a complex history and politics. The book transcends Chilean or Latin American ethnography. I read it as a scholar with general interest in shamans and gender and can recommend it without hesitation to others with the same broad interests.”

Dr. Laurel Kendall

Curator, American Museum of Natural History

“The book is well timed as a rich case study to complement Barbara Tedlock’s overview, The Woman in the Shaman’s Body, which draws on Bacigalupo’s work among others.”

Substitute the term “culture” for “kultrun” and one might well sum up

Bacigalupo’s dialogic ethn... more Substitute the term “culture” for “kultrun” and one might well sum up

Bacigalupo’s dialogic ethnography about the lives, and the hearts and minds of seven Mapuche machi as “The Voice of Culture in Modernity.” Indeed, the kultrun is more than merely a traditional ceremonial drum played by the machi (shamans) in their therapeutic sessions to aid them in ridding their patients from ills that include modern ailments such as stress, depression, lovesickness, alienation, economic problems, AIDS, and cancer. The machi’s drum embodies

the very rhythm through which culture is fashioned and refashioned as it is constantly reinvented by the Mapuche. In light of this, Bacigalupo achieves a new definition of the concept of culture, not as a form of collective corpus, but as an instrument whose tuning and timbre can be changed and whose ragas or tunes are not as much replayed, as they are played with, or can be (re)created on any new occasion. But the tuning obviously needs the tuner, and here the role of the individual (and the Machi, more specifically) in this conception of culture is emphasized. The same malleability is extended to concepts like

identity and tradition, for the author states at the very beginning of her book: “identity, culture, and tradition are dynamic and arise in dialog,

contradistinction, and identification with the other” (p. 9). Nevertheless, one should not mistakenly think that “dialog” here means some kind of rapport or colloquia between two ways of seeing the universe (one traditional, the other modern), for the author shows very clearly that her use of the term preserves the original Greek meaning of multivocality and multireferentiality. Bacigalupo’s book is one of the first truly Bakhtinian ethnographies to be published on ethnomedicine and shamanism.

Marcelo Fiorini, Hofstra University

Articles in English by Ana Mariella Bacigalupo

American Religion, 2024

The introduction to this special issue, "Subversive Religion and More-than-Human Materialities in... more The introduction to this special issue, "Subversive Religion and More-than-Human Materialities in Latin America," conceptualizes the transformative force of practices often gathered under the rubric of "popular religion," including Indigenous, Black, and campesino ritual as well as vernacular Catholicism and Pentecostalism. Rather than treating these practices as manifesting an essential alterity to either the modern state or the "West," we frame them as struggles to build a new world order both against and otherwise than frameworks. Exploring the materiality of these struggles across several dimensions-of the earth, of religious objects and rituals, and of the sovereign body-we describe the constitution of what we call the "flesh of justice" and probe its subversive effects. Drawing on the distinctive tradition of Latin American Marxism to contest the separation of the subaltern "otherwise" from the domain of modern politics, we offer two analytics for engaging with the flesh of justice in Latin America: subversive cosmopolitics and theopolitics.

Journal of Anthropological Research , 2024

Judge Karen Atala framed her child custody case against the Chilean Supreme Court within Indigeno... more Judge Karen Atala framed her child custody case against the Chilean Supreme Court within Indigenous Mapuche "shamanic justice," the "spirit of the law," and human rights. We analyze what Atala's case contributes to the literature on sexual diversity, sorcery, and the spirit of the law in both Chilean and Mapuche histories of justice. The case engages the spirit of the law in two senses. First, it reveals the lack of separation between religious and secular law, demonstrating that religion is profoundly embedded in the law, both for the state and for the Mapuche. Second, it refers to the intention behind the law and its interpretation and enforcement, which haunts even the most literalist, fundamental, secular visions of law. After her spiritual transformation, Atala practiced the spirit of Mapuche customary law in the courts but formally justified her judgments using the letter of the Chilean law, demonstrating a fluidity between law and spirituality.

American Religion, 2024

Pan-Indigenous Peruvian norteños respond to political corruption, climate change, and environ... more Pan-Indigenous Peruvian norteños respond to political corruption, climate change, and environmental devastation by engaging Indigenous sentient landscapes as leaders of environmental movements and cocreators of a pan-Indigenous world. They challenge social models of neoliberal capitalism and settler colonialism, which are based on the distinction between the human and more-than-human and promote human exceptionalism. Scholars of political ontology have considered radically different forms of more-than-human persons and their plural ways of being in the world embedded in relations with the state. I argue that more-than-humans are not just alternative ways of being in the world, but frames through which norteños engage in subversive politics to challenge the justice of neoliberal capitalism and the state. By working beyond the theoretical limitations of ontological approaches (ways of being) and the state’s definition of politics, and within the realm of a local, place-based environmental and spiritual politics, I show how the historical dichotomies of Western thought, Western politics and their effects can be disrupted. I also analyze the difficulties of ontological politics in a milieu that does not ascribe to scholarly and political fantasies of Indigenous purity from modernity. Specifically, I analyze the conflicting ways in which norteños engage with more-than-human landscapes to provide a model for radical ethical-environmental-political action, in which community and well-being are defined as humans in relationship to place-as-persons and d the earth is resignified as an anchor for social and climate justice.

The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 2024

Campesinos (peasants) and norteños (northerner entrepreneurs) in highland Huamachuco, la Libertad... more Campesinos (peasants) and norteños (northerner entrepreneurs) in highland Huamachuco, la Libertad, northern Peru-reconcile their mining within Andean practices about the perceived sentience and agency of mountain-ancestors (apus). They do so by engaging in two different types of apu cannibalism that are antithetical to each other. I analyze how the conflict between Andean campesino communities who practice small-scale underground mining on the apu El Toro site, and, the Summa Gold open-pit mining company (owned by former campesinos now norteño) also on apu El Toro, reshapes, on both sides, relationalities with mountain-ancestors and capitalism. I explore miners' practical moral economies with apus, the local government, and legal authorities to secure economic and political benefits as their worlds are transformed by capitalism. I also analyze how the power inequality between campesino and norteño miners shapes these exchanges, their ability to control the limits of extractivism, and the rhetoric around mining contamination.

In Climate Politics and the Power of Religion edited by Evan Berry. Indiana University Press., 2021

Poor mestizos in northern Peru respond to climate change and environmental devastation by engagin... more Poor mestizos in northern Peru respond to climate change and environmental devastation by engaging indigenous sentient landscapes- with the capacity to sense, feel and act- as moral leaders of environmental movements and co-creators of an interethnic world. They challenge social models normalized by neoliberal capitalism and settler colonialism, which are based on the distinction between the human and non-human, culture and nature, and which promote human exceptionalism and environmental devastation. Scholars have considered radically different forms of non-human persons and their multiple ways of being in the world. This ethnography explores how local mestizos engage sentient landscapes ritually and politically to challenge governments and industries as leaders in movements for environmental justice and collective ethics. By working beyond the theoretical limitations of both ontological approaches (different was of being) and political ecology, and within the realm of a local, place-based environmental and spiritual politics, my research shows how the historical dichotomies of Western thought and their effects can be disrupted and displaced. I analyze how Peruvian mestizos engagement with sentient landscapes can provide a model for radical moral-environmental-political action. By defining “community” and “well-being” as humans in relationship-to-places as-persons, poor mestizos resignify “nature” itself as an anchor for social justice.

SUMMARY The Mapuche undead, killed by the Chilean state but lacking funerals to finish them as pe... more SUMMARY The Mapuche undead, killed by the Chilean state but lacking funerals to finish them as persons, remain trapped in the places of their deaths. They are both symbols of Mapuche rage against state-sponsored genocide and social agents who play central roles in Mapuche cosmopolitics and multitemporal memory making. While memory studies focus on pastness and national commemorations the celebration of individual martyrs, the undead foreground the collective trauma of all Mapuche killed in a place at different times and realize this trauma in Mapuche everyday lives. These morally complex undead call for justice through revenge and express trauma and cos-mopolitics through two different modalities: first, through vengeful spirits in the river who sow illness at two different massacre sites, accidents, and death indiscriminately among the bodies and spirits of locals to force remembering and call for revenge or repa-rations, even as they make Mapuche healing impossible; second, through the strategic use of revenge in the ritual field to reinforce ethnic cosmopolitics. Here, the undead act as ancestors who grant health to those who follow stringent social and moral norms and perpetuate violence among those who transgress their ethnic, ritual, and moral project. These undead combine spiritual, ecological, social, and political factors with realpolitik to subvert state and non-Mapuche development projects, demand justice, and create avenues for interethnic dialogue.

In 1960, 39‐year‐old Francisca Kolipi was struck by lightning during a devastating earthquake and... more In 1960, 39‐year‐old Francisca Kolipi was struck by lightning during a devastating earthquake and became possessed by the spirit of Rosa Kurin, a deceased thunder machi (shaman). 1 Although many people in her community of Millali came to Francisca for healing, others questioned her legitimacy because she had been initiated so late in life and had had no formal training. Some envied Francisca's wealth and power and called her a sorcerer because she violated Mapuche and Chilean patriarchal gender norms: she made her money independently outside the home, and some community members thought she did not distribute sufficient favors to the community; she refused to remarry when she was widowed; and she was considered by some to be manly, aggressive, and amoral (Bacigalupo 2010, 2014). Aware of these criticisms, Francisca feared that her spirit would not be reborn in a new shaman's body after she died. To make sure that her spirit would not be lost, she demanded during our first face‐to‐face meeting that I write her biography as a " bible. " Machi spirits not only carry history; they make history. These spirits become historical agents as they bring knowledge and power from past shamans into the bodies of new ones, who will also act in history. But spirits are also agents that are cleansed and reinvented in narratives that respond to, as well as shape, the changing social and political needs of the community over time. Machi biographical narratives, including Francisca's, are central to Mapuche engagements with temporality and to the construction of historical consciousness in multiple ways. Mapuche construct complex cycles of remembering and disremembering, and the personhood of spirits, both as historical individuals and as collectively mythologized figures, changes over time.

SUMMARY This article examines how the processes of disremembering, the transformations of memory ... more SUMMARY This article examines how the processes of disremembering, the transformations of memory and personhood, and the rebirth of Mapuche shamans address and cloud issues of social persistence and cohesion in a community. My analysis is grounded in the broader culture of death rituals but also advances a reading of these rituals as expressions of an essentially historical consciousness: how Mapuche shamans such as Francisca Kolipi mediate indigenous engagements with history and historicity. Francisca's personhood was reshaped multiple times through contested processes of disremembering and remembering, and her multiple deaths were rescripted and rehistoricized. Community members erased the negative aspects of Francisca's spirit and merged it with the spirit of her machi predecessor, and Francisca was rehistoricized in a new context in anticipation of the rebirth of her spirit in a new shaman. [personhood, disremembering, memory, shaman, death, history] In 1960, thirty-nine-year-old Francisca Kolipi was struck by lightning during a devastating earthquake and became possessed by the spirit of Rosa Kurin, a deceased thunder machi (shaman). Although many people in her community of Millali came to Francisca for healing, others questioned her legitimacy because she had been initiated so late in life and had no formal training. Some envied Francisca's wealth and power and called her a sorcerer because she violated Mapuche and Chilean patriarchal gender norms: she made her money independently outside the home, and people thought she did not distribute sufficient favors to the community; she refused to remarry when she was widowed; and she was considered by some to be manly, aggressive, and amoral (Bacigalupo 2010, 2014). Aware of these criticisms, Francisca feared that her spirit would not be reborn in a new shaman's body after she died. To make sure that her spirit would not be lost, she demanded during our first face-to-face meeting that I write her biography as a " bible. " Machi spirits not only carry history, they make history. These spirits become historical agents as they bring knowledge and power from past sha-mans into the bodies of new ones, who will also act in history. But spirits are also agents who are cleansed and reinvented in narratives that respond to, as well as shape, the changing social and political needs of the

Mapuche oral shamanic biographies and

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and in... more Mapuche oral shamanic biographies and

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy. [shaman, text,

Bible, mestizo, history, literacy, Mapuche, Chile]

Mapuche oral shamanic biographies and

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and ... more Mapuche oral shamanic biographies and

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy.

Uploads

Books by Ana Mariella Bacigalupo

As a “wild,” drumming thunder shaman, a warrior mounted on her spirit horse, Francisca Kolipi’s spirit traveled to other historical times and places, gaining the power and knowledge to conduct spiritual warfare against her community’s enemies, including forestry companies and settlers. As a “civilized” shaman, Francisca narrated the Mapuche people’s attachment to their local sacred landscapes, which are themselves imbued with shamanic power, and constructed nonlinear histories of intra- and interethnic relations that created a moral order in which Mapuche become history’s spiritual victors. Thunder Shaman represents an extraordinary collaboration between Francisca Kolipi and anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, who became Kolipi’s “granddaughter,” trusted helper, and agent in a mission of historical (re)construction and myth-making. The book describes Francisca’s life, death, and expected rebirth, and shows how she remade history through multitemporal dreams, visions, and spirit possession, drawing on ancestral beings and forest spirits as historical agents to obliterate state ideologies and the colonialist usurpation of indigenous lands. Both an academic text and a powerful ritual object intended to be an agent in shamanic history, Thunder Shaman functions simultaneously as a shamanic “bible,” embodying Francisca’s power, will, and spirit long after her death in 1996, and an insightful study of shamanic historical consciousness, in which biography, spirituality, politics, ecology, and the past, present, and future are inextricably linked. It demonstrates how shamans are constituted by historical-political and ecological events, while they also actively create history itself through shamanic imaginaries and narrative forms.

“The book argues that the bodies of machi shamans, their desires and gendered performances, and their possession by and control over spirits become sites for local conflicts and expressions of identity and difference between Mapuche and non-Mapuche people-the places where power, hierarchy and healing are played out. This is a complex and demanding menu. It assumes deep and intimate ethnographic knowledge of her subject, a subtle sense of Chilean history, and agility with theories of gender, performance, and ritual, a tough project but she brings it off. The book comes come in a brilliant final chapter where Bacigalupo and her informants debate her mention of “witchcraft” and “homosexuality,” foregrounding the difficulty of generalizing between machi and the stakes of different machi in presenting themselves and being represented by clients, anthropologists, the Chilean nation, and a New-Age Audience.”

“This is a significant contribution to the field, first as a detailed and complex presentation of machi shamans and as a challenging confrontation of any simple generalization about gender and spirit possession. As a work of ethnography, it sets a high standard for both depth of on the ground knowledge of machi lives, and for its ability to relate those lives to a complex history and politics. The book transcends Chilean or Latin American ethnography. I read it as a scholar with general interest in shamans and gender and can recommend it without hesitation to others with the same broad interests.”

Dr. Laurel Kendall

Curator, American Museum of Natural History

“The book is well timed as a rich case study to complement Barbara Tedlock’s overview, The Woman in the Shaman’s Body, which draws on Bacigalupo’s work among others.”

Bacigalupo’s dialogic ethnography about the lives, and the hearts and minds of seven Mapuche machi as “The Voice of Culture in Modernity.” Indeed, the kultrun is more than merely a traditional ceremonial drum played by the machi (shamans) in their therapeutic sessions to aid them in ridding their patients from ills that include modern ailments such as stress, depression, lovesickness, alienation, economic problems, AIDS, and cancer. The machi’s drum embodies

the very rhythm through which culture is fashioned and refashioned as it is constantly reinvented by the Mapuche. In light of this, Bacigalupo achieves a new definition of the concept of culture, not as a form of collective corpus, but as an instrument whose tuning and timbre can be changed and whose ragas or tunes are not as much replayed, as they are played with, or can be (re)created on any new occasion. But the tuning obviously needs the tuner, and here the role of the individual (and the Machi, more specifically) in this conception of culture is emphasized. The same malleability is extended to concepts like

identity and tradition, for the author states at the very beginning of her book: “identity, culture, and tradition are dynamic and arise in dialog,

contradistinction, and identification with the other” (p. 9). Nevertheless, one should not mistakenly think that “dialog” here means some kind of rapport or colloquia between two ways of seeing the universe (one traditional, the other modern), for the author shows very clearly that her use of the term preserves the original Greek meaning of multivocality and multireferentiality. Bacigalupo’s book is one of the first truly Bakhtinian ethnographies to be published on ethnomedicine and shamanism.

Marcelo Fiorini, Hofstra University

Articles in English by Ana Mariella Bacigalupo

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy. [shaman, text,

Bible, mestizo, history, literacy, Mapuche, Chile]

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy.

As a “wild,” drumming thunder shaman, a warrior mounted on her spirit horse, Francisca Kolipi’s spirit traveled to other historical times and places, gaining the power and knowledge to conduct spiritual warfare against her community’s enemies, including forestry companies and settlers. As a “civilized” shaman, Francisca narrated the Mapuche people’s attachment to their local sacred landscapes, which are themselves imbued with shamanic power, and constructed nonlinear histories of intra- and interethnic relations that created a moral order in which Mapuche become history’s spiritual victors. Thunder Shaman represents an extraordinary collaboration between Francisca Kolipi and anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, who became Kolipi’s “granddaughter,” trusted helper, and agent in a mission of historical (re)construction and myth-making. The book describes Francisca’s life, death, and expected rebirth, and shows how she remade history through multitemporal dreams, visions, and spirit possession, drawing on ancestral beings and forest spirits as historical agents to obliterate state ideologies and the colonialist usurpation of indigenous lands. Both an academic text and a powerful ritual object intended to be an agent in shamanic history, Thunder Shaman functions simultaneously as a shamanic “bible,” embodying Francisca’s power, will, and spirit long after her death in 1996, and an insightful study of shamanic historical consciousness, in which biography, spirituality, politics, ecology, and the past, present, and future are inextricably linked. It demonstrates how shamans are constituted by historical-political and ecological events, while they also actively create history itself through shamanic imaginaries and narrative forms.

“The book argues that the bodies of machi shamans, their desires and gendered performances, and their possession by and control over spirits become sites for local conflicts and expressions of identity and difference between Mapuche and non-Mapuche people-the places where power, hierarchy and healing are played out. This is a complex and demanding menu. It assumes deep and intimate ethnographic knowledge of her subject, a subtle sense of Chilean history, and agility with theories of gender, performance, and ritual, a tough project but she brings it off. The book comes come in a brilliant final chapter where Bacigalupo and her informants debate her mention of “witchcraft” and “homosexuality,” foregrounding the difficulty of generalizing between machi and the stakes of different machi in presenting themselves and being represented by clients, anthropologists, the Chilean nation, and a New-Age Audience.”

“This is a significant contribution to the field, first as a detailed and complex presentation of machi shamans and as a challenging confrontation of any simple generalization about gender and spirit possession. As a work of ethnography, it sets a high standard for both depth of on the ground knowledge of machi lives, and for its ability to relate those lives to a complex history and politics. The book transcends Chilean or Latin American ethnography. I read it as a scholar with general interest in shamans and gender and can recommend it without hesitation to others with the same broad interests.”

Dr. Laurel Kendall

Curator, American Museum of Natural History

“The book is well timed as a rich case study to complement Barbara Tedlock’s overview, The Woman in the Shaman’s Body, which draws on Bacigalupo’s work among others.”

Bacigalupo’s dialogic ethnography about the lives, and the hearts and minds of seven Mapuche machi as “The Voice of Culture in Modernity.” Indeed, the kultrun is more than merely a traditional ceremonial drum played by the machi (shamans) in their therapeutic sessions to aid them in ridding their patients from ills that include modern ailments such as stress, depression, lovesickness, alienation, economic problems, AIDS, and cancer. The machi’s drum embodies

the very rhythm through which culture is fashioned and refashioned as it is constantly reinvented by the Mapuche. In light of this, Bacigalupo achieves a new definition of the concept of culture, not as a form of collective corpus, but as an instrument whose tuning and timbre can be changed and whose ragas or tunes are not as much replayed, as they are played with, or can be (re)created on any new occasion. But the tuning obviously needs the tuner, and here the role of the individual (and the Machi, more specifically) in this conception of culture is emphasized. The same malleability is extended to concepts like

identity and tradition, for the author states at the very beginning of her book: “identity, culture, and tradition are dynamic and arise in dialog,

contradistinction, and identification with the other” (p. 9). Nevertheless, one should not mistakenly think that “dialog” here means some kind of rapport or colloquia between two ways of seeing the universe (one traditional, the other modern), for the author shows very clearly that her use of the term preserves the original Greek meaning of multivocality and multireferentiality. Bacigalupo’s book is one of the first truly Bakhtinian ethnographies to be published on ethnomedicine and shamanism.

Marcelo Fiorini, Hofstra University

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy. [shaman, text,

Bible, mestizo, history, literacy, Mapuche, Chile]

performances—some of which take the form of

“bibles” and involve shamanic literacies—play a

central role in the production of indigenous history

in southern Chile. In this article, I explain how and

why a mixed-race Mapuche shaman charged me with

writing about her life and practice in the form of

such a “bible.” This book would become a ritual

object and a means of storing her shamanic power

by textualizing it, thereby allowing her to speak to a

future audience. The realities and powers her “bible”

stored could be extracted, transformed, circulated,

and actualized for a variety of ends, even to bring

about shamanic rebirth. Ultimately, I argue, through

their use and interpretation of this kind of “bible,”

Mapuche shamans expand academic notions of

indigenous history and literacy.

una machi mestiza mapuche-alemana del

sur de Chile de fines del siglo XIX, expresa una

‘conciencia histórica chamánica’ que anticipa

los debates actuales sobre la relación dinámica

entre la historia y el mito y entre la historia

indígena y la historia nacional. La mitohistoria

biográfica es un género mixto que media entre

diferentes memorializaciones del pasado para

borrar la historia chilena dominante y crear

historias indígenas alternativas. Las mitohistoriaschamánicas

mapuche son simultáneamente

lineales y cíclicas: los personajes históricos se

transforman en personajes míticos y a veces

nuevamente en históricos, y los acontecimientos

míticos se manifiestan en repetidas ocasiones

como sucesos históricos. Los Mapuche

crean mitohistorias mitificando a chamanes y

a personas históricas de afuera, priorizando la

capacidad espiritual de accionar por encima de

ANA MARIELLA BACIGALUPO

179

la capacidad política de accionar, y revirtiendo

desde la narrativa la dinámica colonial habitual

de subordinación. Las mitohistorias son, para

los Mapuche rurales, una manera de expresar

la capacidad de accionar, la identidad étnica y

la ontología. Por otro lado, ofrecen un modo

de descolonizar la historia mapuche y tienen el

potencial para la movilización política.

Palabras clave: machi; conciencia histórica;

mito; historia; Mapuche; Chile.

LAS LUCHAS MAPUCHE (...)The biographical mythohistory of Rosa Kurin, an ethnically mixed Mapuche-German shaman in southern Chile in the late 1800s, expresses a 'shamanic historical consciousness' that advances current debates over the dynamic relationship between history and myth and between indigenous and national history. Biographical mythohistory is a mixed genre that mediates among different memoralisations of the past to obliterate dominant Chilean history and to create alternative indigenous histories. Mapuche shamanic mythohistories are simultaneously linear and cyclical: historical personages are transformed into mythical characters and sometimes back again, and mythical happenings manifest themselves repeatedly in historical events. Mapuche people create mythohistories by mythologising such shamans and historical outsiders, prioritising spiritual agency over political agency and narratively reversing the usual colonial dynamics of subordination. Mythohistories are, for rural Mapuche, a means of conveying agency, ethnic identity and ontology. They also offer a way to decoloniseMapuche history and have the potential for political mobilisation.