Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court |

|---|

|

| Court Information |

| Justices: 7 |

| Founded: 1692 |

| Location: Boston |

| Salary |

| Associates: $226,187[1] |

| Judicial Selection |

| Method: Gubernatorial appointment of judges |

| Term: Until 70 years of age |

| Active justices |

Founded in 1692, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court is the state's court of last resort and has seven judgeships. The chief of the court is Kimberly S. Budd, who was confirmed to the position on November 18, 2020. The court is the oldest continuously functioning appellate court in the Western Hemisphere. Originally called the Superior Court of Judicature, it was established in 1692. The court's name was changed to its current one by the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.[2]

As of April 2024, one judge on the court was appointed by a Democratic governor and six judges were appointed by a Republican governor.

The court meets in the John Adams Courthouse in Boston, Massachusetts.[3]

In Massachusetts, state supreme court justices are selected through direct gubernatorial appointment. Justices are appointed directly by the governor without the use of a nominating commission.[4] There are five states that use this selection method. To read more about the gubernatorial appointment of judges, click here.

Jurisdiction

The supreme judicial court hears appeals for a broad range of criminal and civil cases. The court is also responsible for oversight of the judiciary and the bar, and operations of the courts. The supreme judicial council has varying supervisory responsibilities over the Board of Bar Overseers, Commission on Judicial Conduct, Board of Bar Examiners, Clients Security Board, Legal Assistance Corporation, Mental Health Legal Advisors Committee, and Prisoners' Legal Services of Massachusetts. [5][6]

Unusually, the supreme judicial council may also provide advisory opinions, upon request to the governor and the state legislature. Between 1780-1990 the court issued 364 advisory opinions, 39% initiated by the state house, 31% by the senate, 8% by the governor, 8% requested jointly by both the house and senate, 12% jointly by the governor and governor's council, and 2% by the council alone. The requests can be broken down to five broad topic categories including institutional power, procedures, federal power, potential impact of certain legislative or constitutional changes, and the effect of existing legislation or constitutional provisions.[7][8]

Justices

The table below lists the current judges of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, their political party, and when they assumed office.

| Office | Name | Party | Date assumed office |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Elizabeth Dewar | Nonpartisan | January 12, 2024 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Frank M. Gaziano | Nonpartisan | August 18, 2016 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Serge Georges Jr. | Nonpartisan | December 16, 2020 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Scott L. Kafker | Nonpartisan | August 21, 2017 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Dalila Wendlandt | Nonpartisan | December 4, 2020 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court | Gabrielle R. Wolohojian | Nonpartisan | April 22, 2024 |

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice | Kimberly S. Budd | Nonpartisan | December 1, 2020 |

Judicial selection

- See also: Judicial selection in Massachusetts

The seven justices of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court are appointed by the governor with the approval of the Governor's Council. The Governor's Council is constitutionally authorized and advises the governor on government affairs in Massachusetts. The council is composed of eight members and is elected biennially by the voters. Judges on the supreme court serve until the mandatory retirement age of 70.[9]

Qualifications

Judges of this court must be under the age of 70.[9]

Chief justice

The chief justice is also appointed by the governor with council approval, serving until age 70 as well.[9]

Vacancies

Vacancies on the supreme court are filled by the governor with the approval of the Governor's Council. Judges serve until the mandatory retirement age of 70.[9]

The map below highlights how vacancies are filled in state supreme courts across the country.

Caseloads

The table below details the number of cases filed with the court and the number of dispositions (decisions) the court reached in each year.[10][11]

| Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court caseload data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Filings | Dispositions |

| 2023 | 149 | 148 |

| 2022 | 167 | 151 |

| 2021 | 162 | 173 |

| 2020 | 211 | 197 |

| 2019 | 208 | 217 |

| 2018 | 194 | 195 |

| 2017 | 217 | 227 |

| 2016 | 229 | 196 |

| 2015 | 193 | 201 |

| 2014 | 228 | 205 |

| 2013 | 225 | 211 |

| 2012 | 231 | 200 |

| 2011 | 264 | 194 |

| 2010 | 231 | 231 |

| 2009 | 285 | 205 |

| 2008 | 214 | 222 |

Analysis

Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters (2021)

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters, a study on how state supreme court justices decided the cases that came before them. Our goal was to determine which justices ruled together most often, which frequently dissented, and which courts featured the most unanimous or contentious decisions.

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters, a study on how state supreme court justices decided the cases that came before them. Our goal was to determine which justices ruled together most often, which frequently dissented, and which courts featured the most unanimous or contentious decisions.

The study tracked the position taken by each state supreme court justice in every case they decided in 2020, then tallied the number of times the justices on the court ruled together. We identified the following types of justices:

- We considered two justices opinion partners if they frequently concurred or dissented together throughout the year.

- We considered justices a dissenting minority if they frequently opposed decisions together as a -1 minority.

- We considered a group of justices a determining majority if they frequently determined cases by a +1 majority throughout the year.

- We considered a justice a lone dissenter if he or she frequently dissented alone in cases throughout the year.

Summary of cases decided in 2020

- Number of justices: 7

- Number of cases: 194

- Percentage of cases with a unanimous ruling: 98.5%% (191)

- Justice most often writing the majority opinion: Justice Kafker (25)

- Per curiam decisions: 51

- Concurring opinions: 16

- Justice with most concurring opinions: Justice Gants (7)

- Dissenting opinions: 1

- Justice with most dissenting opinions: Justice Lowy (1)

For the study's full set of findings in Massachusetts, click here.

Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship (2020)

- See also: Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship

Last updated: June 15, 2020

Last updated: June 15, 2020

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship, a study examining the partisan affiliation of all state supreme court justices in the country as of June 15, 2020.

The study presented Confidence Scores that represented our confidence in each justice's degree of partisan affiliation, based on a variety of factors. This was not a measure of where a justice fell on the political or ideological spectrum, but rather a measure of how much confidence we had that a justice was or had been affiliated with a political party. To arrive at confidence scores we analyzed each justice's past partisan activity by collecting data on campaign finance, past political positions, party registration history, as well as other factors. The five categories of Confidence Scores were:

- Strong Democrat

- Mild Democrat

- Indeterminate[12]

- Mild Republican

- Strong Republican

We used the Confidence Scores of each justice to develop a Court Balance Score, which attempted to show the balance among justices with Democratic, Republican, and Indeterminate Confidence Scores on a court. Courts with higher positive Court Balance Scores included justices with higher Republican Confidence Scores, while courts with lower negative Court Balance Scores included justices with higher Democratic Confidence Scores. Courts closest to zero either had justices with conflicting partisanship or justices with Indeterminate Confidence Scores.[13]

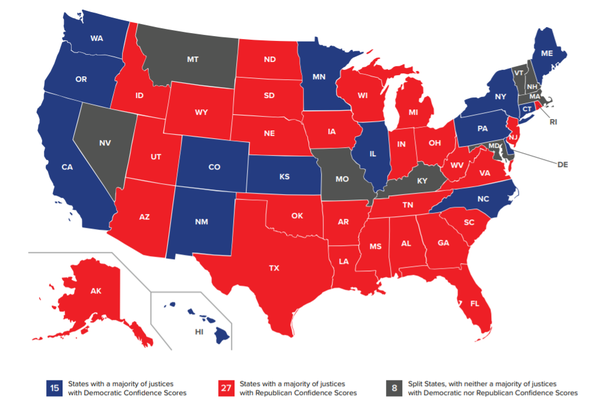

Massachusetts had a Court Balance Score of 0.57, indicating Split control of the court. In total, the study found that there were 15 states with Democrat-controlled courts, 27 states with Republican-controlled courts, and eight states with Split courts. The map below shows the court balance score of each state.

Bonica and Woodruff campaign finance scores (2012)

In October 2012, political science professors Adam Bonica and Michael Woodruff of Stanford University attempted to determine the partisan outlook of state supreme court justices in their paper, "State Supreme Court Ideology and 'New Style' Judicial Campaigns." A score above 0 indicated a more conservative-leaning ideology while scores below 0 were more liberal. The state Supreme Court of Massachusetts was given a campaign finance score (CFscore), which was calculated for judges in October 2012. At that time, Massachusetts received a score of -0.44. Based on the justices selected, Massachusetts was the 11th most liberal court. The study was based on data from campaign contributions by judges themselves, the partisan leaning of contributors to the judges, or—in the absence of elections—the ideology of the appointing body (governor or legislature). This study was not a definitive label of a justice but rather an academic gauge of various factors.[14]

Noteworthy cases

The following are noteworthy cases heard before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. For a full list of opinions published by the court, click here. Know of a case we should cover here? Let us know by emailing us.

| • Court says photos secretly taken up a woman's skirt are legal (2014) | Click for summary→ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court handed down a ruling on March 5, 2014, that said the practice of secretly taking a photo or video up a person's clothing, also known as "upskirting," is legal under state law. The defendant in the case was Michael Robertson, who was arrested in 2010 for using his cell phone to take pictures and video up the skirts or dresses of female passengers on the public trolley. After the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) received multiple complaints, they caught him in the act by sending an undercover female officer onto the trolley. He was charged with two counts of attempting to secretly photograph a person in a state of partial nudity. The court's decision that Robertson's actions were legal was based on the fact that a woman wearing a skirt or dress is not considered partially nude. Therefore, the court ruled in favor of Robertson and granted his request to dismiss the case. The ruling stated:

The court further explained that the state law "does not apply to photographing (or videotaping or electronically surveilling) persons who are fully clothed."[15] Suffolk County District Attorney Daniel Conley responded to the ruling by saying, "Every person, male or female, has a right to privacy beneath his or her own clothing...If the statute as written doesn't protect that privacy, then I'm urging the Legislature to act rapidly and adjust it so it does."[15] Legislative action: | ||||

| • Court finds no authority to detain based on immigration requests | Click for summary→ |

|---|---|

|

On July 24, 2017, a unanimous Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that Massachusetts law does not authorize state court officials to detain someone based solely on a request by federal immigration authorities.[19] Federal authorities make that request using a civil detainer. A civil detainer asks state officials to detain someone because the federal government believes he or she may be subject to removal from the country. In this case, the plaintiff, Sreynuon Lunn, was arrested for a violation of Massachusetts law. While he was in state custody, Massachusetts court officials received a civil detainer asking them to detain Lunn. Before federal authorities arrived, the charge against Lunn was dismissed. Relying on the civil detainer, state officials refused to release him, and he was later turned over to federal immigration authorities. Lunn filed suit, alleging that court officials were not legally authorized to keep him in custody after his case was dismissed.[19] The Massachusetts Supreme Court first noted that “compliance by State authorities with immigration detainers is voluntary, not mandatory.” As the federal government acknowledged, the court wrote, civil detainers “are simply requests. They are not commands, and they impose no mandatory obligations on the State authorities to which they are directed.” In other words, the court concluded, Massachusetts law “may authorize Massachusetts officers to…make arrests for Federal offenses (unless preempted by Federal law), but it need not do so.”[19] Therefore, the court said, the question was whether the law authorized court officials to detain someone based solely on a civil detainer. The court examined Massachusetts and federal law to identify the specific circumstances under which the law empowered court officials to arrest or detain someone. Noting all those circumstances, the court ruled that “Massachusetts law provides no authority for Massachusetts court officers to arrest and hold an individual solely on the basis of a Federal civil immigration detainer, beyond the time that the individual would otherwise be entitled to be released from State custody.”[19] | |

Ethics

Removal of justices

Judges in Massachusetts may be removed from office in three different ways. If there is an allegation of misconduct, the Massachusetts Commission on Judicial Conduct first investigates the complaint. The investigation is followed by a formal hearing. The commission then issues a recommendation to the Massachusetts Supreme Court that the judge, who committed the misconduct, be removed, reprimanded, or be retired from the bench. Governors may also remove a judge, once they have the approval of the governor's council, and with the joint address of both houses of the general court. Governors, again with the approval of the governor's council, may also require judges to retire from the bench, once they have reached the mandatory retirement age or due to a mental or physical disability. Judges may also face removal through impeachment by the Massachusetts House of Representatives and then by conviction by the Massachusetts Senate."[20]

History of the court

The superior court of judicature was established in 1692 by the general court, the legislative arm of the government, according to royal charter, as a trial and appellate court with five justices. The charter also established three lower courts: county justices of the peace, quarter sessions of the peace, and county courts of common pleas. The governor of Massachusetts, appointed by the king of England, had the right to appoint judges and veto general court decisions. Some of the court's first cases in 1693 were appeals related to 26 witchcraft convictions from the village of Salem, where 23 were found not guilty on appeal, and the remaining three were pardoned by the governor. Some decisions of this the superior court of judicature could be appealed to courts in England.[21]Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

In 1800, the legislature increased the size of the court to seven justices. After several more changes in the number of justices on the court, the number has remained at seven since 1873. The increased number was put into place to deal with the increasing caseload of the court. Justices continue to have lifetime appointments with good behavior and may remain in office until the age of 70.[22]

As the appellate load of the supreme judicial court grew, the legislature removed some of the court's trial jurisdiction, including removal of jurisdiction over tort cases in 1880 and over murder cases in 1891 and gave those jurisdictions to the state superior court. An appeals court was created in 1972, after being initially proposed in 1927, and after an intensive campaign for its creation due to the supreme judicial court's considerable workload. Chief Justice Joseph Tauro called it "the most significant development in the organization of our judicial system since the establishment of the superior court in 1859."[23][24]

The governor appoints members of the court with the approval from the elected eight-member executive council.[25]

Noteworthy firsts

- The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court has the distinction of being the oldest continuously functioning appellate court in the Western Hemisphere.

- Three chief justices of the Supreme Judicial Court later served on the U.S. Supreme Court. They were William Cushing, Horace Gray and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Courts in Massachusetts

- See also: Courts in Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, there is one federal district court, a state supreme court, a state court of appeals, and trial courts with both general and limited jurisdiction. These courts serve different purposes, which are outlined in the sections below.

Click a link for information about that court type.

The image below depicts the flow of cases through the Massachusetts state court system. Cases typically originate in the trial courts and can be appealed to courts higher up in the system.

Party control of Massachusetts state government

A state government trifecta is a term that describes single-party government, when one political party holds the governor's office and has majorities in both chambers of the legislature in a state government. A state supreme court plays a role in the checks and balances system of a state government.

Massachusetts has a Democratic trifecta. The Democratic Party controls the office of governor and both chambers of the state legislature.

See also

External links

- Massachusetts Court System, "Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts"

- Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, "Court Decisions"

Footnotes

- ↑ The salary of the chief justice may be higher than an associate justice.

- ↑ Massachusetts Court System, "About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed January 29, 2015

- ↑ Commonwealth of Massachusetts, "Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court," accessed August 25, 2021

- ↑ Note: In New Hampshire, a judicial selection commission has been established by executive order. The commission's recommendations are not binding.

- ↑ Mass.gov,"About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"Affiliated Entities of the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Western New England Law Review,"The Oldest Court of Continuous Existence in the Western Hemisphere," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 National Center for State Courts, "Methods of Judicial Selection: Massachusetts," accessed August 25, 2021

- ↑ Mass.gov, "Court reports," accessed October 5, 2022

- ↑ Massachusetts Court System, "SJC Case Statistics FY 2022 - FY 2023," accessed September 27, 2024

- ↑ An Indeterminate score indicates that there is either not enough information about the justice’s partisan affiliations or that our research found conflicting partisan affiliations.

- ↑ The Court Balance Score is calculated by finding the average partisan Confidence Score of all justices on a state supreme court. For example, if a state has justices on the state supreme court with Confidence Scores of 4, -2, 2, 14, -2, 3, and 4, the Court Balance is the average of those scores: 3.3. Therefore, the Confidence Score on the court is Mild Republican. The use of positive and negative numbers in presenting both Confidence Scores and Court Balance Scores should not be understood to that either a Republican or Democratic score is positive or negative. The numerical values represent their distance from zero, not whether one score is better or worse than another.

- ↑ Stanford University, "State Supreme Court Ideology and 'New Style' Judicial Campaigns," October 31, 2012

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 CNN, "‘Upskirt’ ban in Massachusetts signed into law," March 7, 2014

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Massachusetts Legislature, "Bill H.3934: An Act relative to unlawful sexual surveillance," accessed August 24, 2021

- ↑ NPR: The Two-Way, "Mass. Lawmakers Rework Measure That Permitted 'Upskirt' Photos," March 6, 2014

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Massachusetts Supreme Court, Lunn v. Commonwealth Slip opinion, filed July 24, 2017

- ↑ American Judicature Society, "Methods of Selection: Removal of Judges," accessed March 24, 2015

- ↑ Mass.gov,"About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"Appeals Court History," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"About the Supreme Judicial Court," accessed June 19, 2024

- ↑ Mass.gov,"Learn more about the Judicial Nominating Process," accessed June 19, 2024

Federal courts:

First Circuit Court of Appeals • U.S. District Court: District of Massachusetts • U.S. Bankruptcy Court: District of Massachusetts

State courts:

Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court • Massachusetts Appeals Court • Massachusetts Superior Courts • Massachusetts District Courts • Massachusetts Housing Courts • Massachusetts Juvenile Courts • Massachusetts Land Courts • Massachusetts Probate and Family Courts • Boston Municipal Courts, Massachusetts

State resources:

Courts in Massachusetts • Massachusetts judicial elections • Judicial selection in Massachusetts

| ||||||||