Authors: Gordon Brander, Ben Follington

A collection of theories, patterns, tricks, and intuitions about generative UI. Begins with high-level theory, and works its way down to pragmatic notes on practice.

Generative UI should be capable of emergence. Emergence is when a system’s behavior is more than the sum of its parts.

Emergent systems exhibit:

- Change: emergent systems are constantly in flux. These changes are often nonlinear, and can be difficult to predict.

- Patterns: generative systems aren’t just random. General structures arise and repeat.

- Rules: underneath emergence is a system of rules, or a grammar.

Examples of emergence:

- Complex coordination emerging from ants laying down pheromone trails

- Price signals emerging from market trades

- Consciousness emerging from networks of neurons

Required ingredients for emergence:

- Mechanisms, building blocks, modules, subassemblies, that make up the “stuff” of the system.

- Rules, defining how mechanisms are combined.

- Feedback, where the next step is the recursive function of new information plus the sum of all previous steps.

In some some sense, emergence is just the product of these ingredients. There are no extra “hidden” variables. But emergence is not reducible to the sum of these parts. That’s because emergent systems have a “state”, or “memory” that builds up through feedback with their environment. The particular history of a system is the irreducible “magic” ingredient that generates emergent behavior.

Emergence is above all a product of coupled, context-dependent interactions. Technically these interactions, and the resulting system, are nonlinear. (John H. Holland, 1998, Emergence)

When observing an emergent system, watch for these important features:

- Feedback: Produces nonlinear behavior and acts as “memory”.

- Mechanisms: Specific interactions that produce effects.

- Agents: Independent parts of the system where the level of internal cooperation exceeds the level of external cooperation.

- Hierarchy: arises as a byproduct of recursive combination.

- Tipping points: Thresholds where the system shifts from one kind of behavior to another.

- Keystone species: Parts of a mature ecosystem that become load-bearing lynchpins.

- Decentralization: Centralized coordination acts as a severe constraint on emergence. Decentralized systems can try more things in parallel.

More reading:

- Emergence, John H. Holland, 1998

- Thinking in Systems, Donella Meadows, 2008

- Complexity, a guided tour, Melanie Mitchell, 2011

- More is Different, Philip Anderson, 1972

- 50 Years of More is Different, Steven Strogatz, Sara Walker, et al, 2022

Evolution emerges in any system with:

- Mutation

- Memory

- Selection

You can look at many different systems through this lens, including social networks and multiplayer software. It’s not an ecosystem if it doesn’t evolve.

Questions:

- What parts of the system are mutating, changing?

- Where is memory stored? How? Feedback? Culture? In writing? Somewhere else?

- What selection pressures are present? What do they select for? Which should be present?

Emergence arises from mechanisms combined according to some rules. We call this composition, or in mathematics, compositionality.

Compositionality is the principle that a system should be designed by composing together smaller subsystems, and reasoning about the system should be done recursively on its structure. (Jules Hedges, On Compositionality)

Other related concepts are modularity and reductionism. However compositionality takes things a step further. It is a formal mathematical property, requiring composition without side-effects.

More generally, I claim that the opposite of compositionality is emergent effects. The common definition of emergence is a system being “more than the sum of its parts”, and so it is easy to see that such a system cannot be understood only in terms of its parts, i.e. it is not compositional. Moreover I claim that non-compositionality is a barrier to scientific understanding, because it breaks the reductionist methodology of always dividing a system into smaller components and translating explanations into lower levels. (Jules Hedges, On Compositionality)

We said earlier that we want emergence, so what gives? Well, emergence is difficult to reason about using our limited symbolic cognition.

Compositionality can be a useful property for parts of a system that require proofs of particular properties. Compositionality is easily treatable through mathematics precisely because it excludes the messy nonlinear effects of emergence.

Here we see that emergence in rule-governed systems comes close to being the obverse of reduction. (John H. Holland, 1998, Emergence)

How do you get compositionality? Avoid state, avoid mutation, compose pure functions.

Know where in the system you want emergence, and where in the system you want compositionality.

More reading:

- On Compositionality, Jules Hedges, 2017

- Compositional components, emergent protocols, Gordon Brander

The most expressive generative systems compose at multiple levels.

- Letters combine into words, which describe ideas.

- DNA basepairs combine into genes, which encode traits.

- Minecraft lets you craft new blocks with new properties from combinations of other blocks.

When components of an alphabet are combined, they often express meanings which are different in kind to the alphabet that makes them up. Each new level of meaning forms another alphabet, at another level.

Each level has path-dependencies on the levels beneath. Lower levels constrain higher ones.

At each level of observation the persistent combinations of the previous level constrain what emerges at the next level. (John H. Holland, 1998, Emergence)

The most powerful generative systems enable composition at multiple levels. This allows for great expressive power across different kinds of meanings, at multiple levels of complexity.

Noam Chomsky famously has a theory that language is reducible to a kind of structured grammar. Maybe he’s right, maybe not. Regardless, a lot of the theoretical underpinnings he developed are tremendously useful when reasoning about grammatical systems... any system with a kit of parts and rules for combining them.

The Chomsky hierarchy of languages became a fundamental underpinning of formal language theory and computer science. It is used to reason about everything from parsers to regular expressions.

It states that four different classes of formal grammars exist, which can generate increasingly complex language:

- Regular (simplest)

- Context-free

- Context-sensitive

- Recursively enumerable (most complex)

Each subsequent class can generate the language of all simpler classes, plus more.

This way of reasoning about grammar systems is useful for more than just language, and can be applied to many kinds of generative system that include modularity, hierarchy, and variety (for example, see “Generative Grammars” below).

Combinatorial space maps the possible states of a system as a landscape. This way of seeing can be applied to many systems. Evolutionary biologists think of the possibility space of traits as a fitness landscape, or the possibility space of phenotypes as a morphospace. AI researchers can think of the loss function of an algorithm as a loss landscape.

You will run into three kinds of combinatorial spaces:

- Simple landscape: picture a landscape with a single hill. Optimization problems are simple landscapes.

- Rugged landscape: imagine a mountain range with many peaks and valleys, many right and wrong answers. Optimization doesn’t work here. Hill climbing will get you stuck on the nearest peak (local maxima), thinking it is the highest peak. Tradeoffs dominate. A bit of adventurous random wandering is beneficial.

- Dancing landscape: imagine the roiling waves of a stormy ocean. You can summit a peak, but the peaks don’t stand still. If you want to survive, you’ll have to keep moving.

When building ecosystems, we’re trying to create a dancing landscape.

More reading:

Open-endedness is a special condition that arises in some emergent systems. Many systems will settle toward a single state, or cycle through just a handful of states.

We want a general-purpose generative UI system to be open-ended, because open-endedness is where innovation comes from. The innovation comes from the system surprising itself.

It turns out that continually generating innovation is difficult to do. AIs and evolutionary algorithms tend to converge and get stuck. Yet, we know that some systems do seem to continually innovate: people continue to invent new things, markets continue to disrupt incumbents, life keeps evolving new species.

So how do we create generative systems capable of continual innovation? That’s an ongoing area of research in AI and evolutionary computing, called “open-endedness”. We don’t have answers yet, just heuristics.

A basic requirement for open-endedness is unlimited composition. For example, DNA has just four basepairs, but no limits on the length of the chain. If the chain were limited to 8, 10, 200 basepairs, the combinatorial space of DNA would be constrained. The lack of a limit on length acts as an enabler for open-endedness.

One way to get open-endedness is to cheat and import it:

- People are open-ended.

- Turing-complete scripting is open-ended.

What prevents open-endedness?

- Fixed categories: imposing top-down categorization ends open-endedness before it has a chance to start. The categorization creates a fixed possibility space. DOA. Consider how the App Store app categories are fixed. What if you create an innovation that doesn’t fit into these categories? It’s banned, by definition.

- Fixed filters: culling possibilities according to a fixed set of rules has the same effect as fixed categories. It causes convergence. The rules must evolve with the game.

- Fixed roles: in nature, hierarchy and specialization arise from the bottom-up, not from the top-down. These ecosystems role are contextual and constantly changing.

- Fixed fitness functions: by definition, these create fixed possibility landscapes. In Signals and Boundaries, John H. Holland points out that a truly open-ended fitness function would have to take in the whole world-state as its input. In other words, fitness in nature is defined by coevolution between species. It’s constantly changing and being changed as everything else changes.

More reading:

- Open-endedness: The last grand challenge you’ve never heard of, Kenneth O. Stanley, Joel Lehman and Lisa Soros

- Stepping stones in possibility space

- Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned, Kenneth O. Stanley, Joel Lehman, 2015

Variety is a measure of how many different states a system can produce... literally by just counting them.

The Law of Requisite Variety says “who has the most variety drives the plot”.

Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety: The variety of a regulator must be at least as large as that of the system it regulates.

When observing an ecosystem, ask:

- Who has the most variety?

- How is the variety generated?

- Variety is limited by inputs. Where are the inputs? What limits them?

Generative systems are made of mechanisms, or building blocks, or modules.

Your goal in designing a generative system is to find a set of mechanisms that can be combined to generate desired behaviors, as well as other interesting behaviors beyond those you can ask for and imagine.

Getting there requires a lot of play, and an eye for recognizing where you can draw a line around a building block, and which building blocks are open-ended.

Consider the lego dot. It’s a simple interface. Every lego, no matter the shape exposes this same interface. That means every lego can be combined with every other lego. The combinatorial space of a lego pair is the exponent of every lego brick. The more universal the API, the broader the combinatorial space, the more kinds of unexpected combinations can occur.

So, create universal interfaces. For example, don’t just create a verb, create a verb that can act on many objects.

Verbs that can act on many objects. This is possibly the single most powerful thing you can do to make an interesting game. If you give a player a gun that can only shoot bad guys, you have a very simple game. But if that same gun can be used to shoot a lock off a door, break a window, hunt for food, pop a car tire, or write a message on the wall, now you start to enter a world of many possibilities. (The Art of Game Design, by Jesse Schell)

More reading:

A good generating system is often just carefully selected ingredients, rules, and randomness.

The quality of the meal depends upon the quality of the ingredients. Garbage in, garbage out. Take a look at a successful generative system and you’ll see carefully crafted components:

- Every tarot card has a rich tapestry of symbols, laden with multiple meanings. These symbols interact in rich ways when you combine different cards and layouts.

- Each Oblique Strategy is calibrated to provoke maximum generative ambiguity.

- Lego colors and shapes are carefully chosen to work together and combine to make interesting structures.

Ingredients and rules provide guidance, randomness creates surprise.

Sometimes we can create generative systems where the possibility space contains mostly good, or only good solutions. This tends to work best with more constrained generators, and where you can carefully curate the ingredients and rules.

Examples:

- There are no bad I-Ching hexagrams

- There are no incorrect Tarot card combinations

- Color palette generators can be designed to always produce useful combinations by constraining specific contrast ranges and relationships (complementary, triadic, etc)

You can often create generators that are very expressive, yet consistently deliver impressive results. They seem to seek toward good outcomes. Yet, it is still worth noting that there is a fundamental tradeoff between constraint and expressivity.

In practice we often want tools that ride this line between constraint and expressivity. Consider a pottery wheel. It constrains movement along one axis (vertical), but amplifies your agency to express ideas along another (horiztonal). Consider what axes of agency are meaningful in a given context.

It can sometimes be useful to start with a less expressive generative system that has only “good answers”, and progressively excavate mechanisms that enable more expressivity over time.

In software, we talk about the Unix Philosophy:

- Write programs that do one thing and do it well.

- Write programs to work together.

- Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

This set of intuitions will serve us well when designing generative systems.

- Create mechanisms that do one thing and do it well.

- Create mechanisms to work together

- Create mechanisms with universal interfaces

An interface is a language for communicating with computers. When you’re designing generative UI, you’re designing an alphabet.

What is an alphabet? A kit of parts, plus rules for combining them.

Consider your generative system through the lens of language:

- What are the letters, words, sentences, paragraphs?

- What is the grammar by which these things are combined?

- What are the parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives...)?

More reading:

- Systems Generating Systems, Christopher Alexander, 1968

- Controls as Language, Max Kreminski, 2016

- Alphabets of emergence

- Alphabets

When designing alphabets for emergence, constrain the alphabet, but don't constrain what may be written with it.

- Constrain the alphabet. Keeping the alphabet small makes it easy to learn. It also forces you, the designer, to create a composable alphabet. With a smaller set of letters, expressiveness is achieved by designing rules that allow letters to be composed with each other in many different ways.

- ...But don't constrain what may be written with it. Alphabets that produce open-ended emergence — written language, chemistry, DNA — don't place a limit on the number of letters you may combine in sequence, or the meanings you may construct with those letters. Anything achievable within the rules of the alphabet is permissible. This generates an open-ended possibility space.

DNA has a tiny alphabet (ATCG), but no limit on the number of basepairs that may be chained together, and no constraint, outside of natural selection, on the phenotypes that may be generated. The web defines a set of technologies (HTML, CSS, JavaScript), and rules for combining them, and does not censor what may be created with those technologies. This permissionless system continues to generate surprising new business models.

Failure modes:

- Large alphabets with many different interfaces. These don’t create large combinatorial spaces, since composition is severely constrained.

- Censorship: this is a kind of post-filtering that limits downside, but also upside.

When we shape the possibility space by way of shaping the alphabet, we enable open-ended innovation. When we cull generated results via fixed rules, we cause the system to converge.

More reading:

In general:

- Putting a lower-bound on quality will restrict variety. When all output is “equally interesting”, nothing is interesting. “Information is the difference that makes a difference” (Gregory Bateson). Capping downside caps upside.

- Increasing depth or breadth reduces control but increases interest. Minecraft has voxels and finite block types for a reason.

A generative system can be emergent, and even open-ended without being interesting. Kate Compton calls this the 10,000 bowls of oatmeal problem:

I can easily generate 10,000 bowls of plain oatmeal, with each oat being in a different position and different orientation, and mathematically speaking they will all be completely unique. But the user will likely just see a lot of oatmeal. (Kate Compton, So you want to build a generator)

What makes a generative system interesting? Perceptual uniqueness. You’ll know it when you see it.

Assuming you generate a valid output, the cause of the oatmeal problem is that the observer sees "the shape of the algorithm" at work rather than the output itself. This is visible in classic Perlin-noise based terrain generation:

Every hill, valley and coast feel the same despite actually being unique. By contrast, modern terrain generation (using Houdini) has clear archetypes we recognize from the real world with discernible "locations" on them:

The goal is to create outputs from a generative system that have "personality". Each should be unique but also mappable into a taxonomy by a willing scientist. When composing an interesting song there must be a balance of repetition and variation, tension and release. Generative composition is no different. The taxonomy of options forms due to feedback through intentionally designed channels of the system, each with varying dynamics.

You can produce archetype-like behaviors in a generative system by mixing different dynamics. For example, Perlin noise alone makes for relatively uninteresting terrain but with the addition of erosion the landscape becomes cohesive:

In this case, we have one dynamic acting per-texel (Perlin noise) and one dynamic acting across the entire heightmap iteratively in a cellular automata (erosion). Operating across different scales and dimensions of the problem space allows for patterns that appear organic.

Aside from scale and dimension, dynamics can also differ in shape. Consider a smooth vs. spiky curve:

Mixing different shapes, scales and dimensions together results in a kind of "constrained chaos" confined to a particular manifold of the generative space.

You can gain an intuition for a generating system by creating scripts that generate many permutations, giving you a sample of the possibility space.

Years ago when working on a project with challenging color palette I did the craziest thing and just listed all possible color combinations and then manually selected the best ones. Turns out it was 10x faster than hunting bad cases one by one or trying to come up with an algo. https://twitter.com/marcinignac/status/1484211214477627392

What if your generative system isn’t “smart enough” and keeps producing broken combinations? It might be that your generative system doesn’t have requisite variety to do what you want. Maybe you’re overshooting?

In these situations you can usually get unstuck by coarse-graining the generative system. Instead of generating Lego Technic, try Lego, or even Duplo. Instead of generating stories from letters, try generating them from words or paragraphs, or pre-canned story segments.

Evolutionary algorithms often get stuck this way. You try to evolve a useful digital solution from 1s and 0s, but keep getting slop. The solution? Design artificial DNA where basepairs encode whole useful traits! No wrong answers!

There’s obviously a tradeoff between coarse-graining, expressivity, and open-endedness, but when you’re on the wrong side of expressivity, it can be a pragmatic solution.

More reading:

You can often start with a coarse-grained set of generative components, and progressively excavate finer-grained components over time. This approach can have advantages:

- You can make progress quickly in the beginning by “black-boxing” certain complex components

- You can uncover finer-grained alphabets as your generative algorithms get smarter/improve in quality

- It can help nudge you toward layered API designs and alphabets that compose at multiple scales.

Think of this like blocking out large portions of a canvas while painting. You paint large swaths with a wide brush before moving on to the details.

One IRL example of mechanism excavation is The Extensible Web Manifesto, which seeks to “explain existing and new features in terms of low-level capabilities”.

Note that there are also tradeoffs in becoming extremely fine-grained. As the system becomes more expressive, it shifts requisite variety away from the system and toward developers. This increases open-endedness, sacrifices the system’s ability to control certain properties. For example, on the web, we see this manifest as complaints about JavaScript bundle size (which is the other side of the tradeoff of providing many fine-grained mechanisms rather than coarse-grained platform components). Know where you want the system to uphold guarantees, and consider coarse-graining those portions to keep the requisite variety on the system’s side.

Many procedural generation systems fail because they attempt too much in a single step. Dwarf Fortress generates an world with a complete historical record and does so by simulating the entire thing (with some smoke and mirrors).

Caves of Qud generates similar histories through a layered symbolic expansion. This presentation covers their approach in detail but here is a brief sketch:

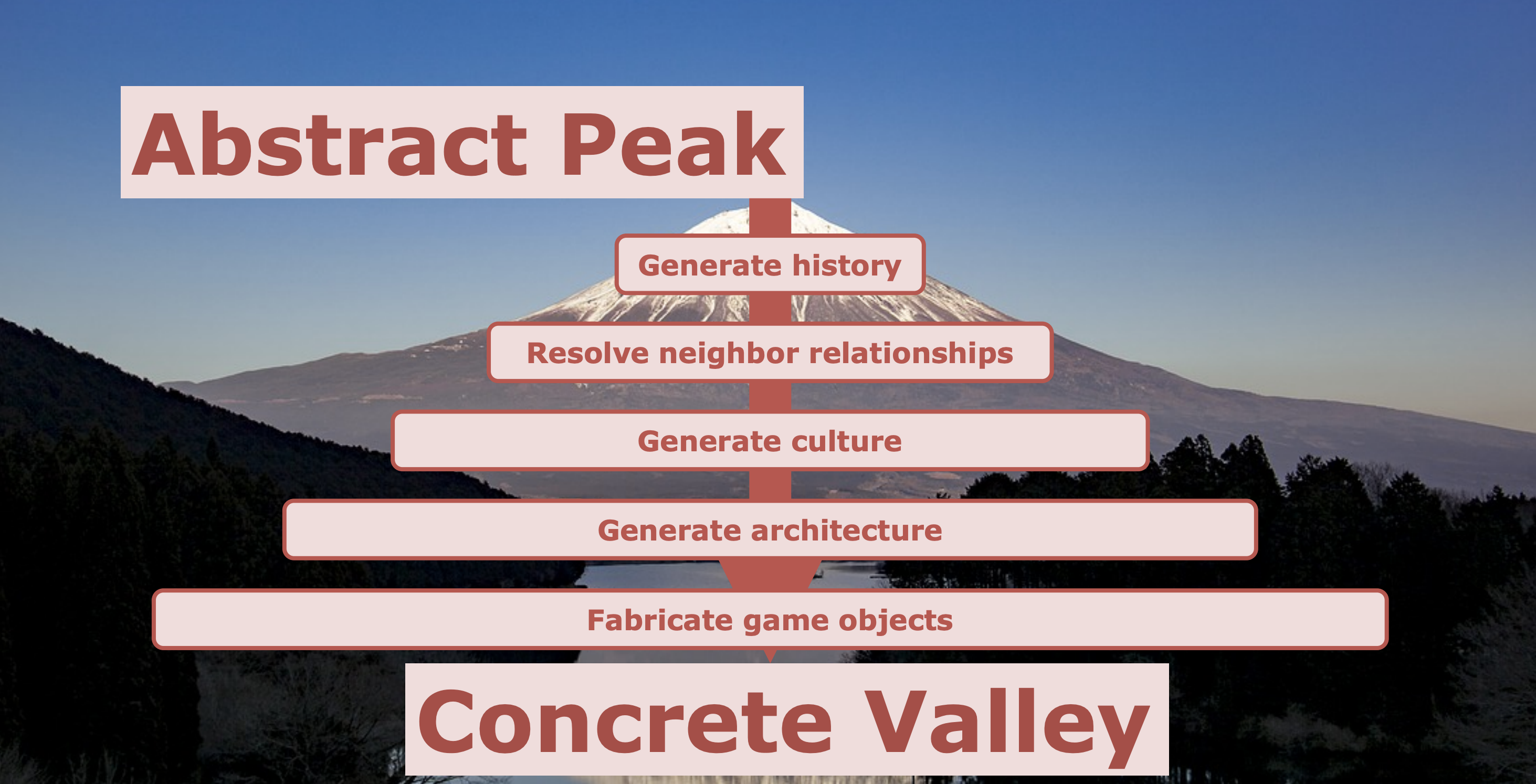

We take many iterative passes to go from the Abstract Peak to the Concrete Valley:

This town was created when the founder ?name discovered it.

This town was created when the founder, Jessica, discovered it while doing ?something.

This town was created when the founder, Jessica, discovered it while gathering water and saw ?something.

This town ?name was created when the founder, Jessica, discovered it while gathering water and saw a mole hill.

This town Moleville was created when the founder, Jessica, discovered it while gathering water and saw a mole hill.

Each time we append more information we have the choice of drawing entities from the existing pool or generating new ones or clarifying details. Currently we know this town:

- has a source of water

- has a mole hill

- is called Moleville

- has a founder named Jessica

When we come to generate the actual physical layout of this town, we might take a generic approach and then refine using these details:

- spawn a point of interest placeholder

- spawn 4 unlabelled houses

- spawn a pond

- add rooms to houses by subdividing

- replace the point of interest with a molehill

- label the house nearest to the point of interest as "Jessica's house"

When the player arrives here, it will seem like this village organically formed, because it did!

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. Sometimes it can be beneficial to break out of the generative mindset and script, design, or interfere with a step in the process:

Examples:

- WeChat offers AI assistants for everything from banking to restaurants. These AIs cheat on two levels. One, by breaking out of free text, and presenting structured user interfaces for chat interaction. Two, by seamlessly dropping down to a real human behind the curtain when they aren’t sure what to do.

- Open world video games often have scripted sequences, story bottlenecks you have to pass through, or levels that unlock when certain story conditions are met.

Questions:

- Am I stuck? How can I cheat?

- Can I cheat without breaking the fundamental open-endedness and generativity of the system?

Designing generative systems requires a special kind of mindset - a gardening mindset.

An architect, at least in the traditional sense, is somebody who has an in-detail concept of the final result in their head, and their task is to control the rest of nature sufficiently to get that built. Nature being things like bricks and sites and builders and so on. Everything outside has to be subject to an effort of control.

A gardener doesn't really work like that. Unless it's, as Mark's mentioned, Versailles, which is, to me, the most grotesque of all gardens, since it's the total denial of nature and the complete expression of human control over nature. So it's a perfect forerunner to the Industrial Age, Versailles. But what I think about, I suppose my feeling about gardening, and I suppose most people's feeling about gardening now, is that what one is doing is working in collaboration with the complex and unpredictable processes of nature. And trying to insert into that some inputs that will take advantage of those processes, and as Stafford Beers said, take you in the direction that you wanted to go.

Use the dynamics of the system to take you in the direction you wanted to go. So my feeling has been that the whole concept of how things are created and organized has been shifting for the last 40 or 50 years, and as I said, this sequence of science as cybernetics, catastrophe theory, chaos theory and complexity theory, are really all ways of us trying to get used to this idea that we have to stop thinking of top-down control as being the only way in which things could be made.

We have to actually lose the idea of intelligent design, because that's actually what that is. The top-down theory is the same as intelligent design. And we have to actually stop thinking like that and start understanding that complexity can arise in another way and variety and intelligence and so on. So my own response to this has been, as an artist, to start to think of my work, too, as a form of gardening. So about 20 years ago I came up with this idea, this term, 'generative music,' which is a general term I use to cover not only the stuff that I do, but the kind of stuff that Reich is doing, and Terry Riley and lots and lots of other composers have been doing. (Brian Eno Composers as Gardeners)

More reading:

- Composers as Gardeners, Brian Eno

- Seeing Like a State, James C Scott, 1999

Synchronization happens through feedback, so:

- If the error rate is too high, tighten the feedback loop.

- If the variety is too low, loosen the feedback loop.

Instead of looking at a generative system and saying “it’s not good enough”, ask “how can I tighten the feedback loop with the user?”

The brilliance of Google’s “10 blue links” is that it allows for zero-friction feedback. Google doesn’t have to get it right, it just has to get it right in 10 tries! And what if everyone clicks the third link from the top? Well, Google can bump it up.

Imagine if Google only had “I’m Feeling Lucky”? That would be pretty frustrating! Yet this is how most people think about AI and generative systems. “Get it right in one try” will always be unlikely. Instead, try to find a low-friction ways to increase feedback.

On the other hand, if the system is not generating enough variety, it may mean you’re too synchronized. Loosen up that feedback loop.

More reading:

That means they aren’t great at deeply recursive reasoning. For example, ask the LLM to close progressively deeper sequences of parenthesis... It will get it right, but at some high depth, it will eventually begin to fail.

It’s a pretty typical kind of thing to see in a “precise” situation like this with a neural net (or with machine learning in general). Cases that a human “can solve in a glance” the neural net can solve too. But cases that require doing something “more algorithmic” (e.g. explicitly counting parentheses to see if they’re closed) the neural net tends to somehow be “too computationally shallow” to reliably do. (By the way, even the full current ChatGPT has a hard time correctly matching parentheses in long sequences.) (What is ChatGPT doing? And why does it work?, Stephen Wolfram, 2023)

So, LLMs don’t do well with deeply interdependent logic puzzles, or problems that have a deeply recursive structure.

One way we can deal with this is to “unroll the loop”... to break our deeply recursive problem down into a sequence of steps that can be solved via multi-shot prompting.

Another approach is to farm out the problem. Computations of arbitrary depth? This is exactly what computers good for. So, what if we combined LLMs with other software to get the best of both? It turns out this is exactly what many LLMs do under the hood, farming out computations they’re bad at:

- Calling out knowledge graphs to do automated reasoning.

- Using RAG and function calling to ground responses with search

- Generating Python code, and then interpreting it, to solve computationally deep problems

Questions:

- LLMs are computationally shallow. How computationally deep is my problem?

- In what ways might we combine the LLM with other systems to get the best of both?

More reading:

- What is ChatGPT doing? And why does it work?, Stephen Wolfram, 2023

You may not like it, but this code has high locality of behavior. I don’t have to jump through other functions and files to understand it. @housecor

- LLMs only see what's in the context window and their training data

- LLMs don't do well reasoning about deeply recursive processes.

- LLMs see surface complexity and correlate high-dimensional processes.

An LLM is more likely to be effective at generating code with high locality vs a complex class, where the program execution flow is indirect and threaded throughout class methods, with implicit state mutation, overriding via inheritance, etc. So:

- DONT: action at a distance.

- DONT: separation of concerns

- DO: group related things together

- DO: maximally direct code

- DO: avoid indirection

- DO: encapsulate code

An LLM can be seen as a function of string -> string. This has a few important implications:

- LLMs are composable: The output of an LLM can be the input to an LLM.

- Code is data, data is code: natural language can be seen as an artifact, or as an instructions to the LLM. Text can serve both roles, or change roles over time.

Just use text. The more aspects of your experience that you can express as text, or serialize as text, the more aspects can be understood by the LLM, transformed by the LLM, customized by the LLM.

“Text” should be construed broadly. It can include natural language prompts, markup, JSON, short snippets of JavaScript, or the function calling API.

“Just use text” means hoisting too much into the UI layer (e.g. using nodes and wires instead of prompting) is an anti-pattern. When it’s not expressible as text, you’re not leaning into the power of the medium. Consider making things like UI elements expressible as markup or as React Components that can potentially be given to an LLM, or generated by an LLM.

A common metaphor for AI is that of a godlike oracle. You ask the oracle a question, it delivers an answer.

Q: “What is the meaning of life?” A: 42

This metaphor for AI is not very interesting, because:

- It’s feed-forward

- It’s convergent

- It doesn’t reflect what LLMs actually do today

The hot new thing is AI agents, but agency requires feedback, and LLMs are feed-forward systems. No feedback, no agency.

At the same time, feedback is all you need for agency to emerge. A thermostat has limited agency through feedback with its environment. Likewise, an LLM can be part of an agentic system by introducing feedback.

In 2024, useful autonomous agents may be outside the adjacent possible. A system’s feedback loops evolve over time through experiences within its environment. This process starts from the bottom-up, from simple to complex, from weeds, to bushes, to rainforests. So, the first true AI agents may look more like a virus - simple replicators.

From another angle, we might see LLMs as part of a larger agentic system that includes you. This point of view is pragmatic and empowering. IA (Intelligence Amplification) vs AI (Artificial Intelligence).

More reading:

Another way to see LLMs is as creative tools, like

LLMs are more like Artificial Intuition than Artificial Intelligence.

Reasoning has a deep, recursive shape. LLMs are computationally shallow. An LLM guesses-next-token by assembling good candidates from a massive hyperdimensional field of associations, their model.

Reasoning is deep, LLMs are broad.

What else has this shape? Intuition. Our intuitions are shaped by our experience. Our unconscious draws from these impressions, assembling related impressions together to produce a gut feeling, or an insight, or a dream.

So, we taught computers to do vibes. And vibes are most of what we’re doing when we think, too. The reasoning part of our brain is an aftermarket part, bolted on to our ancient intuition.

What LLMs are likely to be good at:

- Vibes

- Common sense

- Turning fuzzy impressions into concrete statements

- Understanding the gist of things (summarization)

Questions:

- Is my problem broad or deep?

- What might be better solved by intuition than reasoning?

Software is getting softer.

More reading:

- Artificial Intuition, not Artificial Intelligence

- The Kekule Problem, Cormac McCarthy, 2017

- Echopraxia, Peter Watts, 2015

- The Origins of Wealth, Eric D. Beinhocker, 2007

Another way to use an LLM is as a touch-up or synthesis pass.

For example, a generative grammar could be used to generate the outline of a story, and an LLM used to expand that outline into a few paragraphs. This gives you a high degree of control over ingredients and how they are combined. At the same time, generative grammars lack the high-dimensional structure of natural language, It can be difficult to design them in ways that generate natural-sounding paragraphs and sentences, but LLMs are great at this kind of synthesis.

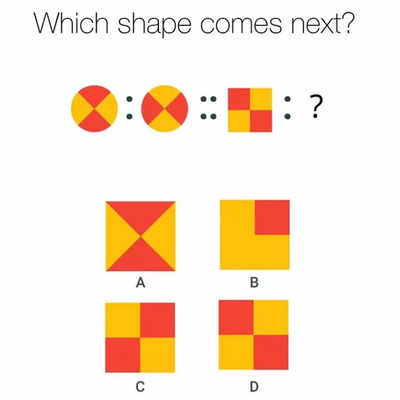

An LLM outputs whatever logically follows from its input. Due to the personification of instructor-tuned models we tend to speak to them conversationally but this often produces poor results. Instead, think of LLMs like those "what comes next in the sequence" puzzles:

A good prompt sketches out the steps of the pattern with minimal distraction surrounding them. This is why examples are so effective for LLMs, they provide evidence of a pattern to extend. Good prompting means thinking backwards from the intended output to produce the most compact set of tokens that will logically lead to it.

Instruction-tuned LLMs struggle with open problem descriptions. More capable models can deal with more ambiguity but the best results come from extremely clear problem specification (much like the real world).

What is a novel theory in the field of psychology?

🙅 This is a pretty bad question, even for a person. What answer are you expecting for this?

Find a recent psychology literative review

---

Describe 5 of the the promising areas of investigation identified in a short paragraph, mentioning the original article title and author

---

Suggest 5 ways these areas of investigation could be related to one another, are there opportunities for collaboration?

---

Formulate each suggestion into a research question (AKA hypothesis)

👍 This is a textual program that generates text, not a question.

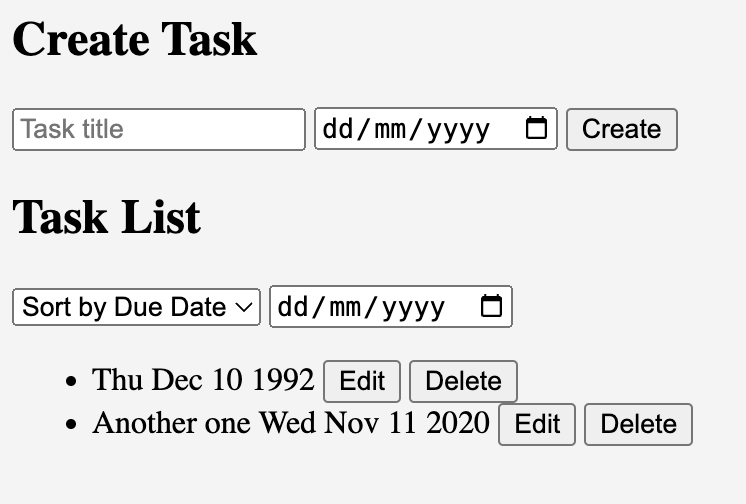

It can be helpful to throw away the context mid-generation and tightly manipulate it through many passes. For example, let's make an app for this request:

"I want a todo application that lets me add due dates"

The full script is available, but the general steps are:

- Generate Domain Model from description

- Generate data API from domain model

- Improve description by considering UI/UX implementation

- Plan full-app build using UI + description + data API

- Implement the plan

- Check the app for errors, ensure it meets the specification

https://github.com/instructor-ai/instructor-js

Storylets are a way of organizing procedurally generated narrative.

Components of a storylet:

- An atomic piece of content (line, paragraph, section, animation, cutscene...)

- Prerequisites for the content to play

- Effects on the world state after it plays

Note that this structure can be used for more than narrative. It neatly combines atomic designed units, algorithmic guidance, user input, and randomness to enable a wide range of applications.

Lots of games use this basic structure, and it’s flexible enough to support many semi-open story structures, including gauntlets, branching and bottlenecks, “sorting hats”, eternal return, and more.

Examples of games that use Storylets:

More reading:

- Storylets: You Want Them

- Survey of storylet design

- Sketching a map of the storylets design space, Max Kreminski, 2018

Abstract principle: begin with mostly noise and use specific mathematical operations to extract signal.

(psuedo)randomness is the fundamental starting point for any computational process relying on variety. Mixing multiple types of noise together at different scales and parameterising them is a common way to disguise the obvious patterns of algorithmic noise.

WFC is effectively playing Sudoku to generate a grid-based output. First tiles are placed at random, which reduces the pool of valid tiles that can be placed next to them. If there is only one valid possibility for a space, we can safely lock it in which continues to "collapse" the wave function iteratively across the grid. Depending on the tileset it may not deterministically find a full solution.

This video provides an excellent overview of the technique in practice and the sharp edges you might bump into: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIRTOgfsjl0

SDF geometry discards the classic vertex, edge, face structure of a mesh and renders geometry using a mathematical functions to describe the volume.

This allows for far deeper control over shape generation and deeply parametric design. Tools like womp and people like Inigo Quilez (of Pixar fame) are pushing this as the next-generation approach.

SDFs are also finding use in parametric font-rendering. Importantly, SDFs can be re-topologized to mesh based geometry if needed.

Diffusion models have risen to popularity for image, video and audio geneation but the same principle also tranfers to SDF geometry. Gaussian splats, voxels and SDFs can be used to generate 3D models on demand, albet with compromises to the rendering performance.

https://x.com/eric_heitz/status/1780979459790610503 https://x.com/eric_heitz/status/1780979462256931023

Houdini, Blender, Grasshopper Rhino https://cuttle.xyz

Generative grammars borrow insights from the Chomsky hierarchy, to create a recursively-enumerable grammar that can be expanded into random-yet-structured output.

The core of a generative grammar is a map of keys to lists of values:

{

"name": ["Brittany", "Andrew"],

"animal": ["wombat", "cat"],

"story": [

"This is a story about #name# the #animal.capitalize#",

"This is a tale about a #animal# named #name#"

]

}

Each time the interpreter encounters a #tag#, it selects a random value from the corresponding key in the map. This happens recursively, until there are no more keys to replace.

The random-yet-hierarchically-structured recursive shape of generative grammars is useful for a lot of different generating tasks, including generating stories, combining ingredients for a recipe, creating collections of starting equipment for a game...

Generative grammars hit a sweet spot for simple and expressive:

- Generative grammars are easy to implement. A basic implementation can be written in just a few lines of code.

- Generative grammars are also easy to author. They provide a nice balance of randomness, structure, and authorial control. You can even weight randomness by including the same option multiple times in a list. It’s fairly easy to produce generators which are “good a lot”.

- Generative grammars aren’t limited to text. You can have them generate markup, JSON, file paths to image assets, etc.

There might also be interesting ways to use generative grammars in tandem with LLMs. Generative grammars are stricter about structure, but also “dumber” than LLMs, while LLMs are better at doing common sense things, and “soft” things.

- Use a generative grammar to generate input for an LLM, then have the LLM expand that into natural language, or something else.

- Use an LLM to generate a grammar.

- Use a grammar to structure “soft” outputs from an LLM.

More reading:

- Tracery, Kate Compton

- Practical procedural generation for everyone, Kate Compton

- So you want to build a generator, Kate Compton

A Markov chain or Markov process is a stochastic model describing a sequence of possible events in which the probability of each event depends only on the state attained in the previous event.

While primitive, Markov chains can be significantly simpler, faster and funnier than other techniques and have been used to great effect in games like Caves of Qud.

https://motion.cs.umn.edu/pub/NateBuckThesis/NathanielBuck_ProceduralContent.pdf

An L-system or Lindenmayer system is a parallel rewriting system and a type of formal grammar. An L-system consists of an alphabet of symbols that can be used to make strings, a collection of production rules that expand each symbol into some larger string of symbols, an initial "axiom" string from which to begin construction, and a mechanism for translating the generated strings into geometric structures.

They happen to be excellent at generation branching structures, like plants.

Lindenmayer's original L-system for modelling the growth of algae.

variables : A B

constants : none

axiom : A

rules : (A → AB), (B → A)

which produces:

n = 0 : A

n = 1 : AB

n = 2 : ABA

n = 3 : ABAAB

n = 4 : ABAABABA

n = 5 : ABAABABAABAAB

n = 6 : ABAABABAABAABABAABABA

n = 7 : ABAABABAABAABABAABABAABAABABAABAAB

A cellular automaton consists of a regular grid of cells, each in one of a finite number of states, such as on and off (in contrast to a coupled map lattice). The grid can be in any finite number of dimensions. For each cell, a set of cells called its neighborhood is defined relative to the specified cell. An initial state (time t = 0) is selected by assigning a state for each cell. A new generation is created (advancing t by 1), according to some fixed rule (generally, a mathematical function)[3] that determines the new state of each cell in terms of the current state of the cell and the states of the cells in its neighborhood.

CA's are an extremely broad class of algorithm and despite their grid-based definition they can model all sorts of dynamics. Stephen Wolfram famously laid claim to them and sketched out a vision for their importance in his book A New Kind of Science.

Rather than storing discrete quantities in each grid cell, we could store continuous floating point values and even store multiple different quantities in each cell. This approach is, approximately, how most compute shader simulations work:

This is an active research frontier, especially beyond 2D, see the work of Sage Jensen.

- Systems Generating Systems, Christopher Alexander, 1968

- Computational Design Thinking, Achim Menges, Sean Ahlquist, 2011

- Procedural Generation in Game Design

- Procedural Storytelling in Game Design

- Emily Short's Interactive Storytelling

- So you want to build a generator

#generativedesign #generativegrammar #ai #design #complexty #ui #ux