|

| Click for genus-level Certhioidea tree |

|---|

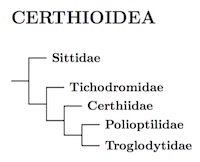

The superfamily Certhioidea is likely sister to the Muscicapoidea and may even be best treated as part of Muscicapoidea. For now, it is not really clear how the various groups that seem allied to Muscicapoidea fit together. Until this is clarified, I prefer to consider Certhioidea an independent superfamily within Passerida, but closely allied with Muscicapoidea. This all has only minor effects on the linear order, but it does affect the shape of the tree.

Following HBW, I've put the wallcreeper in a separate family. The rest is fairly solid, including the position of the nuthatches, and treatment of gnatcatchers and wrens are sister families.

Price et al. (2014) provided genetic evidence that Tichodromidae and Sittidae are ancient sister taxa. Selvatti et al. (2015) obtained a somewhat different arrangement, with Tichodromidae sister to Certhiidae. However, they relied on only two genes for Tichodroma, whereas Price et al. (2014) used 6 genes. Zhao et al. (2016b) found support for both arrangements. In either case, the division between Tichodroma and its sister group is comparable to the separation between other families in Certhioidea, justifying treatment of Tichodromidae as a family. We follow Barker (2017) in placing Tichodromidae on its own branch, as shown on the diagram above.

Sittidae: Nuthatches Lesson, 1828

1 genus, 28 species HBW-13

The arrangement of the nuthatches is based on Pasquet et al. (2014).

White-breasted Nuthatches

I have not adopted the proposed split of the White-breasted Nuthatch, Sitta carolinensis (for details, see Mlodinow, 2014; Spellman and Klicka, 2007; Walstrom et al., 2012). It does deserve some discussion. Spellman and Klicka (2007) found 4 subspecies groups which they referred to as the Eastern; Pacific; Eastern Sierra Nevada (ESN); and Rocky Mountain, Great Basin, and Mexico (RGM) clades. Various subspecies are recognized by various authorities. I will use a relatively expansive version here to cover all the bases.

The Eastern clade (carolinensis group) is resident east of the Great Plains of North America, and includes cookei, litorea, carolinensis, and presumably the possibly extinct atkinsi. The Pacific clade (aculeata group) includes aculeata and presumably alexandrae. The ESN clade (tenuissima group) consists of tenuissima and the northern part of nelsoni. The dividing line between the northern nelsoni and true nelsoni seems to go though the center of Colorado. The birds of the northern Rockies formerly considered part of nelsoni could use a new subspecies name. Finally, the RGM clade (lagunae group) includes, lagunae, true nelsoni, uintaensis, mexicana, and umbrosa. It likely also includes oberholseri and kinneari, although they don't seem to have been sampled. You should not trust the range maps in either Spellman and Klicka (2007) or Walstrom et al. (2012). For example, the type locality for uintaensis (Green Lake, Utah) is not considered part of the range of the WHite-breasted Nuthatch by Walstrom et al. (2012), while neither Walstrom et al., nor Spellman and Klicka show the type locality for oberholseri (Boot Spring, Big Bend, Texas). This got me curious, and I checked eBird. The eBird maps are enlightening here, particularly if you zoom in along the contact zones between the clades.

As is well-known, the 4 clades fall into three call groups: Pacific, ESN/RGM, and Eastern. Spellman and Klicka found relatively deep divisions (up to 3.4 million years) between the three call groups, which a more recent divergence between the ESN and RGM groups. Each of these call groups is a candidate for elevation to species status. Contra Mlodinow (2014), the 3rd edition (1910) of the AOU checklist did not use the name Carolina Nuthatch for carolensis either as a species or subspecies. Nonetheless, it is a fitting name, and does have some history behind it (e.g. Coues, 1903). Slender-billed Nuthatch has traditionally been used for aculeata and can be applied to the Pacific group.

As far as the scientific name of the ESN/RGM group, is concerned, lagunae has priority, and contrary to what one of the NACC committee members thought, has been sampled by Spellman and Klicka (2007). The English name opens up a huge can of worms. Various names have been applied to the various subspecies. These include: San Lucas Nuthatch (lagunae), Rocky Mountain Nuthatch (nelsoni), Inyo Nuthatch (tenuissima), Chisos Nuthatch (oberholseri), Mexican Nuthatch (), Sierra Madre Nuthatch (umbrosa), and Southern White-breasted Nuthatch (kinneari). Although Rocky Mountain Nuthatch has been suggested, much of the range is outside the Rockies, in the Sierra Nevadas, the Sierra Madres, the Chisos, and others. I think Cordilleran Nuthatch would be an appropriate name.

So why not accept the split? Right now, there just isn't enough evidence. Walstrom et al. (2012) considered more genes, and revised the topology, with Carolina basal and Pacific and Cordilleran sister. They also found much shorter divergence dates. Their point estimate was about 550,000 ago for the basal split. This is recent enough to consider them all one species. However, as one of the NACC committee members discussed, aculeata and tenuissima come close to one another in the Sierra Nevadas, being separated by habitat and elevation. There's no hint of interbreeding, but it really hasn't been studied that closely.

The White-breasted Nuthatch may be three species, but as the NACC committee decided, the contact zones need closer study to establish it. The genetics just don't cut it here. Worse, the contact areas seem much more extensive than the NACC appeared to realize. I agree with committee on this one.

- White-cheeked Nuthatch, Sitta leucopsis

Click for Sittidae tree - Przevalski's Nuthatch, Sitta przewalskii

- Giant Nuthatch, Sitta magna

- White-breasted Nuthatch, Sitta carolinensis

- Beautiful Nuthatch, Sitta formosa

- Western Rock-Nuthatch, Sitta neumayer

- Eastern Rock-Nuthatch, Sitta tephronota

- White-tailed Nuthatch, Sitta himalayensis

- White-browed Nuthatch, Sitta victoriae

- Eurasian Nuthatch, Sitta europaea

- Siberian Nuthatch, Sitta arctica

- Kashmir Nuthatch, Sitta cashmirensis

- Indian Nuthatch, Sitta castanea

- Chestnut-bellied Nuthatch, Sitta cinnamoventris

- Chestnut-vented Nuthatch, Sitta nagaensis

- Burmese Nuthatch, Sitta neglecta

- Blue Nuthatch, Sitta azurea

- Velvet-fronted Nuthatch, Sitta frontalis

- Yellow-billed Nuthatch, Sitta solangiae

- Sulphur-billed Nuthatch, Sitta oenochlamys

- Pygmy Nuthatch, Sitta pygmaea

- Brown-headed Nuthatch, Sitta pusilla

- Yunnan Nuthatch, Sitta yunnanensis

- Algerian Nuthatch, Sitta ledanti

- Krueper's Nuthatch, Sitta krueperi

- Red-breasted Nuthatch, Sitta canadensis

- Corsican Nuthatch, Sitta whiteheadi

- Chinese Nuthatch, Sitta villosa

Tichodromidae: Wallcreeper Swainson, 1827

1 genus, 1 species HBW-13

The family name is sometimes spelled Tichodromididae. It was originally established as the subfamily Tichodromia by Swainson, 1827 (Swainson did not use modern subfamily endings).

- Wallcreeper, Tichodroma muraria

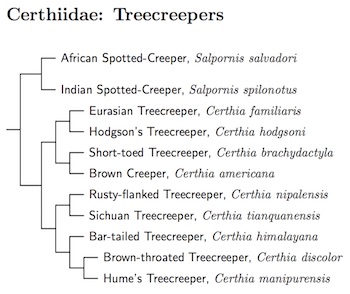

Certhiidae: Treecreepers Leach, 1820

2 genera, 11 species HBW-13

The position of Salpornis has been somewhat controversial. Johansson et al. (2008b) found evidence it is part of the nuthatch clade. Although their results were mixed, and one gene suggested a close relationship to the creepers, Salpornis shares an insertion in β-fibrinogen with nuthatches, gnatcatchers, and wrens that the creepers do not have. Tietze and Martens (2010) noted there are also morphological reasons to group Salpornis with the nuthatches rather than treecreepers. The treecreepers all have stiffened retrices. Nuthatches, Salpornis and the wallcreper do not. Zhao et al. (2016b) also had inconsistent results concerning its placement. However, the latest treatment by Barker (2017) put Salpornis in the creeper clade, and I follow that here.

Based on Tietze and Martens (2010), the Spotted Creeper has been split into African Spotted-Creeper, Salpornis salvadori, and Indian Spotted-Creeper, Salpornis spilonotus, with the subspecies allocated according to geography.

Barker (2017) found that Salpornis is sister to Certhia. Since they are only distant relatives, likely separating at least 15mya, I have placed them in separate subfamilies. The arrangement of Treecreepers follows Päckert et al. (2012b).

Salpornithinae: Spotted Creepers Mayr and Amadon, 1951

- African Spotted-Creeper, Salpornis salvadori

- Indian Spotted-Creeper, Salpornis spilonotus

Certhiinae: Treecreepers Leach, 1820

- Eurasian Treecreeper, Certhia familiaris

- Hodgson's Treecreeper, Certhia hodgsoni

- Short-toed Treecreeper, Certhia brachydactyla

- Brown Creeper, Certhia americana

- Rusty-flanked Treecreeper, Certhia nipalensis

- Sichuan Treecreeper, Certhia tianquanensis

- Bar-tailed Treecreeper, Certhia himalayana

- Brown-throated Treecreeper, Certhia discolor

- Hume's Treecreeper, Certhia manipurensis

Polioptilidae: Gnatcatchers, Gnatwrens Baird, 1858

3 genera, 24 species HBW-12

The ordering of Polioptilidae is based on Smith et al. (2018). The gnatwrens form a clade sister to all of the gnatcatchers.

The gnatcatchers start with a Guianan clade. Here, the Rio Negro Gnatcatcher, Polioptila facilis, and Para Gnatcatcher, Polioptila paraensis, have been split from the Guianan Gnatcatcher, Polioptila guianensis. Also, the newly described Inambari Gantcatcher, Polioptila attenboroughi, is added to the list. See Whitney and Alonso (2005), Whittaker et al. (2013), and Smith et al. (2018).

The Cuban Gnatcatcher, Polioptila lembeyei, is sister to the remaining gnatcatchers, which consist of a clade of former Tropical Gnatcatchers, and a mainly North American clade containing the widespread Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Polioptila caerulea.

Smith et al. (2018) argue in favor of a number of splits. I have adopted the following: The Yucatan Gnatcatcher, Polioptila albiventris, has been split from the White-lored Gnatcatcher, Polioptila albiloris. There are many splits from the Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila plumbea which falls into two unrelated clades. It has been split into a clade that is east of the Andes:

- Eastern Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila atricapilla (NE Brazil).

- Northeastern Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila plumbea (Suriname, French Guiana, and N Brazil).

- Western Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila parvirostris (Amazonian Ecuador and Peru and NW Brazil).

Although range maps indicate the ranges of these three run into each other, they seem to be pretty thin on the ground in the middle. These are joined in this clade by the more southerly Creamy-bellied Gnatcatcher, Polioptila lactea, and the Masked Gnatcatcher, Polioptila dumicola.

The other clade includes the previously mentioned Yucatan Gnatcatcher, Polioptila albiventris, as well as the following split from the Tropical Gnatcatcher.

- White-browed Gnatcatcher, Polioptila bilineata, including daguae, bilineata, cinericia, brodkorbi, and superciliaris. These are white-faced except for daguae (Mexico to Peru, west of the Andes, and the upper Cauca Valley of Colombia).

- Northwestern Tropical Gnatcatcher Polioptila plumbiceps, including innotata, plumbiceps, and anteocularis (upper Magdalena Valley to C Guyana, N Brazil).

- Maranon Gnatcatcher Polioptila maior (upper Marañon Valley).

I have retained the term “Tropical Gnatcatcher” in the name of most of the species east of the Andes, partly to ease the transition, partly because I don't have good names for them. Smith et al. (2018) advocate even more splitting, so this may change again in the future.

- Long-billed Gnatwren, Ramphocaenus melanurus

Click for Polioptilidae tree - Collared Gnatwren, Microbates collaris

- Tawny-faced Gnatwren / Half-collared Gnatwren, Microbates cinereiventris

- Guianan Gnatcatcher, Polioptila guianensis

- Slate-throated Gnatcatcher, Polioptila schistaceigula

- Para Gnatcatcher, Polioptila paraensis

- Rio Negro Gnatcatcher, Polioptila facilis

- Iquitos Gnatcatcher, Polioptila clementsi

- Inambari Gantcatcher, Polioptila attenboroughi

- Eastern Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila atricapilla

- Northeastern Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila plumbea

- Western Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila parvirostris

- Masked Gnatcatcher, Polioptila dumicola

- Creamy-bellied Gnatcatcher, Polioptila lactea

- Cuban Gnatcatcher, Polioptila lembeyei

- Maranon Gnatcatcher, Polioptila maior

- Northwestern Tropical Gnatcatcher, Polioptila plumbiceps

- Yucatan Gnatcatcher, Polioptila albiventris

- White-browed Gnatcatcher, Polioptila bilineata

- Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Polioptila caerulea

- Black-capped Gnatcatcher, Polioptila nigriceps

- White-lored Gnatcatcher, Polioptila albiloris

- Black-tailed Gnatcatcher, Polioptila melanura

- California Gnatcatcher, Polioptila californica

Troglodytidae: Wrens Swainson, 1831

20 genera, 90 species HBW-10

Except for Nannus, the wrens are confined to the Americas, where they are present pretty much everywhere south of the northern treeline. The overall arrangement of the genera is now based on the multigene analysis of Barker (2017). The specie arrangement is based on combined cytochrome b and β-fibrinogen analyses of Barker (2004) and Mann et al. (2006). There is a basal group, which I treat as subfamily Salpinctinae. The affinities of tooth-billed wrens (Odontorchilinae) are not 100% certain, but seem most likely to be sister to the remaining wrens, Troglodytinae. Within Troglodytinae, there are two major clades. One contains Bewick's and Carolina Wrens, together with the large Campylorhynchus wrens. The other contains the remaining wrens.

Following the taxonomic suggestions of Mann et al. (2006), Thryothorus has been separated into 4 genera: Thryothorus, Pheugopedius, Thryophilus, and Cantorchilus. It is uncertain where the Gray Wren, Cantorchilus griseus, actually belongs. It may end up in a separate genus.

I have followed Vázquez-Miranda et al. (2009) in splitting Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus, and Sclater's Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis, from Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha. Although the IOC recognizes this split, the AOU NACC does not. C. capistratus includes nigricaudatus, and presumably xerophilum, nicaraguae, and castaneus. Vázquez-Miranda et al. also found that some of the subspecies of zonatus do not actually belong there, but further study is required to untangle that situation.

In their 65th AOS supplement, the AOS finally caught up with the split of Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha, long recognized by TiF. Two of the names AOS prefers are not those suggested in the 7th ed. of the AOU checklist. Accordingly, I'm renaming the Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha, to Veracruz Wren. However, I've only added Russet-naped Wren to the name of Sclater's Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis.

At the species level, the wrens currently seem to be somewhat overlumped. The arrangement here includes several species that are not currently recognized by either of the AOU committees, although some are recognized in HBW-10 (Kroodsma and Brewer, 2005). The splits that go beyond any of these involve the Winter Wren, Troglodytes troglodytes. Based on Drovetski et al. (2004a) and Toews and Irwin (2008), I've split it into 3 species: Pacific Wren, Winter Wren, and Eurasian Wren. These are placed in a new genus, Nannus. The Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis, includes the subspecies hiemalis and pullus. The other North American subspecies are included in Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus. Drovetski et al. included several Aleutian wrens in their analysis, and found that they grouped tightly with pacificus. I am presuming that all of the western subspecies will be close to pacificus. Toews and Irwin studied pacificus and hiemalis where their ranges overlap slightly along the northern British Columbia/Alberta boundary. They found evidence of a high degree of reproductive isolation, which prompts the split here. The eurasian races have not been as closely studied. Drovetski et al. found they form a monophyletic clade sister to Nannus hiemalis. Further, they found there are at least four separate clades that may deserve species rank: troglodytes/indigenus, hyrcanus, nipalensis, and fumigatus/dauricus. As you can see, many eurasian subspecies were not included. I prefer to wait for more information before further splitting the Eurasian Wren.

Among the Troglodytes house wrens I recognize several non-AOU species that Kroodsma and Brewer (2005) also split. Thus we have the North American Northern House Wren, Troglodytes aedon; the Mexican Brown-throated Wren, Troglodytes brunneicollis (which ranges into the mountains of SE Arizona); Cozumel Wren, Troglodytes beani; the Falklands endemic Cobb's Wren, Troglodytes cobbi, which the SACC is again considering recognizing; and the South and Central American Southern House Wren, Troglodytes musculus. Exactly how these all relate is not clear, and whether they truly deserve species status remains unclear (see Brumfield and Capparella, 1996; Rice et al., 1999; Martínez Gómez et al., 2005; Campagna et al., 2012). It has been argued that Antillean races of the Southern House Wren also deserve species rank.

Kroodsma and Brewer (2005) include one more split that I have not followed, splitting White-browed Wren, Thryothorus albinucha, from Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus. Mann et al. (2006) provide some supporting evidence for this split, but they do not recommend them at this time.

Lara et al. (2012) announced the discovery of the Antioquia Wren, Thryophilus sernai. Their analysis also suggests that the Rufous-and-white Wren may contain two or more species, but I'd like to see more information on this before making further changes.

Possible splits not followed include three in Cistothorus. The eastern and western Marsh Wrens, Cistothorus palustris, are vocally quite different. The same can be said about the northern and southern Sedge Wrens, Cistothorus platensis, where it is not clear exactly how many species are involved or what their limits are. This uncertainty is why they are treated as a single species. Finally, Apolinar's Wren, Cistothorus apolinari, may include two geographically separated species.

Two of the Henicorhina Wood-Wrens are also candidates for future splits (Dingle et al., 2006, 2008, 2010). The White-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucosticta, includes Andean, Chocó, and Central American groups, each of which may deserve species status. The Chocó (inornata) group appears to be more closely related to the Bar-winged Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucoptera (Dingle et al., 2006). In this list, we currently consider it a subspecies of H. leucoptera.

Dingle et al. (2006) also found that the Gray-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucophrys, includes at least 3 clades which might be better considered as species (Central American, Chocó, and Peruvian and Ecuadorian Andes). The Hermit Wood-Wren / Santa Marta Wood-Wren, Henicorhina anachoreta, has been split from Gray-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucophrys. See SACC proposal #700. Caro et al. (2013) focused on the Gray-breasted Wood-Wrens in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of Colombia. The found an altitudial separation in the Santa Martas with a contact zone at about 2270 meters elevation. The highland birds, Hermit Wood-Wren (subspecies anachoreta) seem more closely related to the Gray-breasted Wood-Wrens in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Andes, while the lowland birds, Bangs's Wood-Wren (subspecies bangsi) are more closely related to Gray-breasted Wood-wrens in Venezuela and Colombia. For now, Bang's Wood-Wren is not split. Caro et al.'s analysis suggests there may be additional taxa in this complex worth considering for species status.

Saucier et al. (2016) found that the Plain Wren, Cantorchilus modestus, is actually three species: Cabanis's Wren, Cantorchilus modestus, Canebrake Wren, Cantorchilus zeledoni, and Isthmian Wren, Cantorchilus elutus. The split of Canebrake Wren had previously been advocated by Kroodsma and Brewer (2005). See also Mann et al. (2006).

Gonzalez et al. (2003) analyzed DNA from the Bay Wren, Cantorchilus nigricapillus. They found two major groupings, which could be split into Bay Wren, Cantorchilus castaneus (including odicus, reditus, and costaricensis), and the Black-capped Wren, Cantorchilus nigricapillus (including schottii and connectens).

Salpinctinae: Geophilous Wrens Informal

- Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus

Click for Troglodytidae species tree - Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus

- Sumichrast's Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti

- Nava's Wren, Hylorchilus navai

- Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela

- Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus

- Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus

- Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla

Odontorchilinae: Tooth-billed Wrens Informal

- Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii

- Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus

Troglodytinae: Typical Wrens Swainson, 1831

- Bewick's Wren, Thryomanes bewickii

- Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus

- Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus

- Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis

- Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus

- Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus

- White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus

- Fasciated Wren, Campylorhynchus fasciatus

- Cactus Wren, Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus

- Yucatan Wren, Campylorhynchus yucatanicus

- Giant Wren, Campylorhynchus chiapensis

- Bicolored Wren, Campylorhynchus griseus

- Boucard's Wren, Campylorhynchus jocosus

- Spotted Wren, Campylorhynchus gularis

- Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus

- Sclater's Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis

- Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha

- Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus

- Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis

- Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes

- Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai

- Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris

- Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis

- Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae

- Apolinar's Wren, Cistothorus apolinari

- Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni

- Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus

- Ochraceous Wren, Troglodytes ochraceus

- Mountain Wren, Troglodytes solstitialis

- Santa Marta Wren, Troglodytes monticola

- Rufous-browed Wren, Troglodytes rufociliatus

- Brown-throated Wren, Troglodytes brunneicollis

- Socorro Wren, Troglodytes sissonii

- Clarion Wren, Troglodytes tanneri

- Northern House-Wren, Troglodytes aedon

- Southern House-Wren, Troglodytes musculus

- Cozumel Wren, Troglodytes beani

- Cobb's Wren, Troglodytes cobbi

- Black-throated Wren, Pheugopedius atrogularis

- Happy Wren, Pheugopedius felix

- Speckle-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius sclateri

- Rufous-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius rutilus

- Spot-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius maculipectus

- Sooty-headed Wren, Pheugopedius spadix

- Black-bellied Wren, Pheugopedius fasciatoventris

- Moustached Wren, Pheugopedius genibarbis

- Coraya Wren, Pheugopedius coraya

- Whiskered Wren, Pheugopedius mystacalis

- Plain-tailed Wren, Pheugopedius euophrys

- Inca Wren, Pheugopedius eisenmanni

- White-bellied Wren, Uropsila leucogastra

- Rufous-and-white Wren, Thryophilus rufalbus

- Antioquia Wren, Thryophilus sernai

- Niceforo's Wren, Thryophilus nicefori

- Sinaloa Wren, Thryophilus sinaloa

- Banded Wren, Thryophilus pleurostictus

- Chestnut-breasted Wren, Cyphorhinus thoracicus

- Song Wren, Cyphorhinus phaeocephalus

- Musician Wren, Cyphorhinus arada

- White-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucosticta

- Bar-winged Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucoptera

- Gray-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucophrys

- Hermit Wood-Wren / Santa Marta Wood-Wren, Henicorhina anachoreta

- Munchique Wood-Wren, Henicorhina negreti

- Rufous Wren, Cinnycerthia unirufa

- Sharpe's Wren / Sepia-brown Wren, Cinnycerthia olivascens

- Peruvian Wren, Cinnycerthia peruana

- Fulvous Wren, Cinnycerthia fulva

- Gray Wren, Cantorchilus griseus

- Stripe-throated Wren, Cantorchilus leucopogon

- Stripe-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus thoracicus

- Cabanis's Wren, Cantorchilus modestus

- Canebrake Wren, Cantorchilus zeledoni

- Isthmian Wren, Cantorchilus elutus

- Riverside Wren, Cantorchilus semibadius

- Bay Wren, Cantorchilus nigricapillus

- Superciliated Wren, Cantorchilus superciliaris

- Buff-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus leucotis

- Fawn-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus guarayanus

- Long-billed Wren, Cantorchilus longirostris