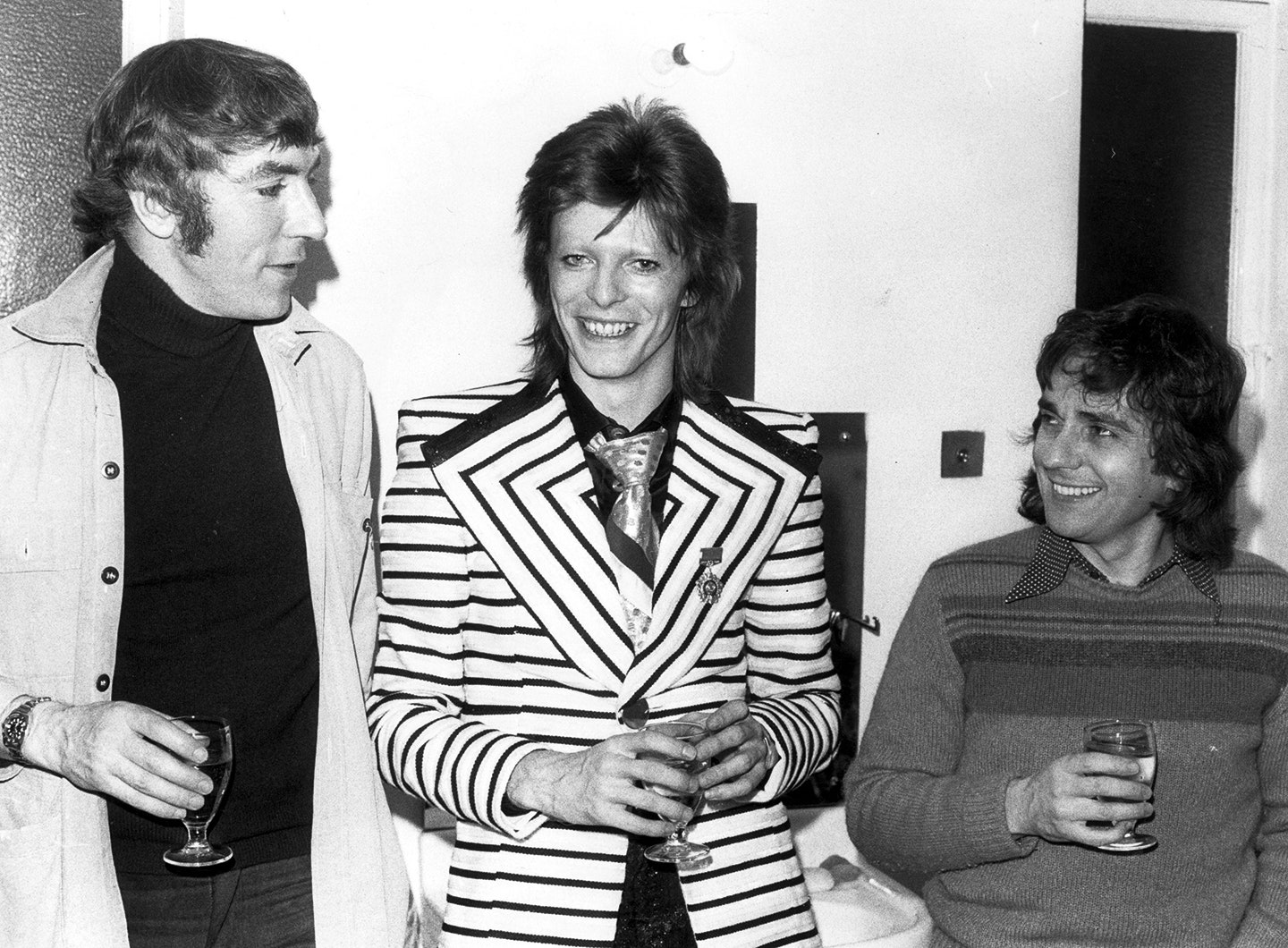

“This album was produced by Ken Scott (assisted by the actor)” reads a credit on the back cover of David Bowie’s 1971 album, Hunky Dory. “The actor” of course was Bowie himself, who’d been trained in mime and appeared in 1967 in a short film in which he played a young artist’s subject whose image came to life and haunted its creator. Think on that for a bit.

Think also on the fact that Hunky Dory contained songs in praise—sincere but hardly uncritical—of two of David Bowie’s artistic heroes, Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol. “Song for Bob Dylan” took a wary look at the knife-edge of dual identity in the realms of creative genius and/or stardom; “Andy Warhol” observed of the pop artist “Andy Warhol, silver screen / Can’t tell them apart at all.”

Bowie’s perceptions of Warhol and Dylan were not just brilliantly astute on their own: as his rock-star career exploded, they proved prescient in their self-awareness. Among the many dizzying things about the man and artist was his sheer intelligence, which seemed to continue to function at an intimidating level even when he was not taking the best care of his corporeal self.

When Bowie, by now world famous, landed his first major film role, as the alien who takes the name Thomas Jerome Newton in director Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 The Man Who Fell to Earth, the question of whether “the actor” could “actually act” was not even really a question. There was never a question of Bowie “disappearing” into his role, done while he was winding out of a harrowing affair with cocaine that nonetheless productively informed some fantastic musical work—his spectacular 76 album Station to Station, resulting in part from Bowie’s failure to concoct soundtrack music for Man, is still an uncanny, desolate work that hasn’t dated a day. Bowie nonetheless gave a superbly modulated performance in The Man Who Fell to Earth, “doing” almost nothing even when the desperate Newton, whose mission to bring water back to his home planet goes terribly off the rails almost right away, is at his most manic. His presence is no less heart-stabbingly poignant for being utterly definitive of “presence.” It is a perfect fit, a strange stillness holding together a deliberately time-and-space-fractured cinematic vision. (It is probably no coincidence that Roeg got the idea of using Bowie from a short 1975 BBC documentary on the star called Cracked Actor, named for a song on Bowie’s Aladdin Sane.) If he never acted in another film after it, he would still be a giant of cinema, like Maria Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc.

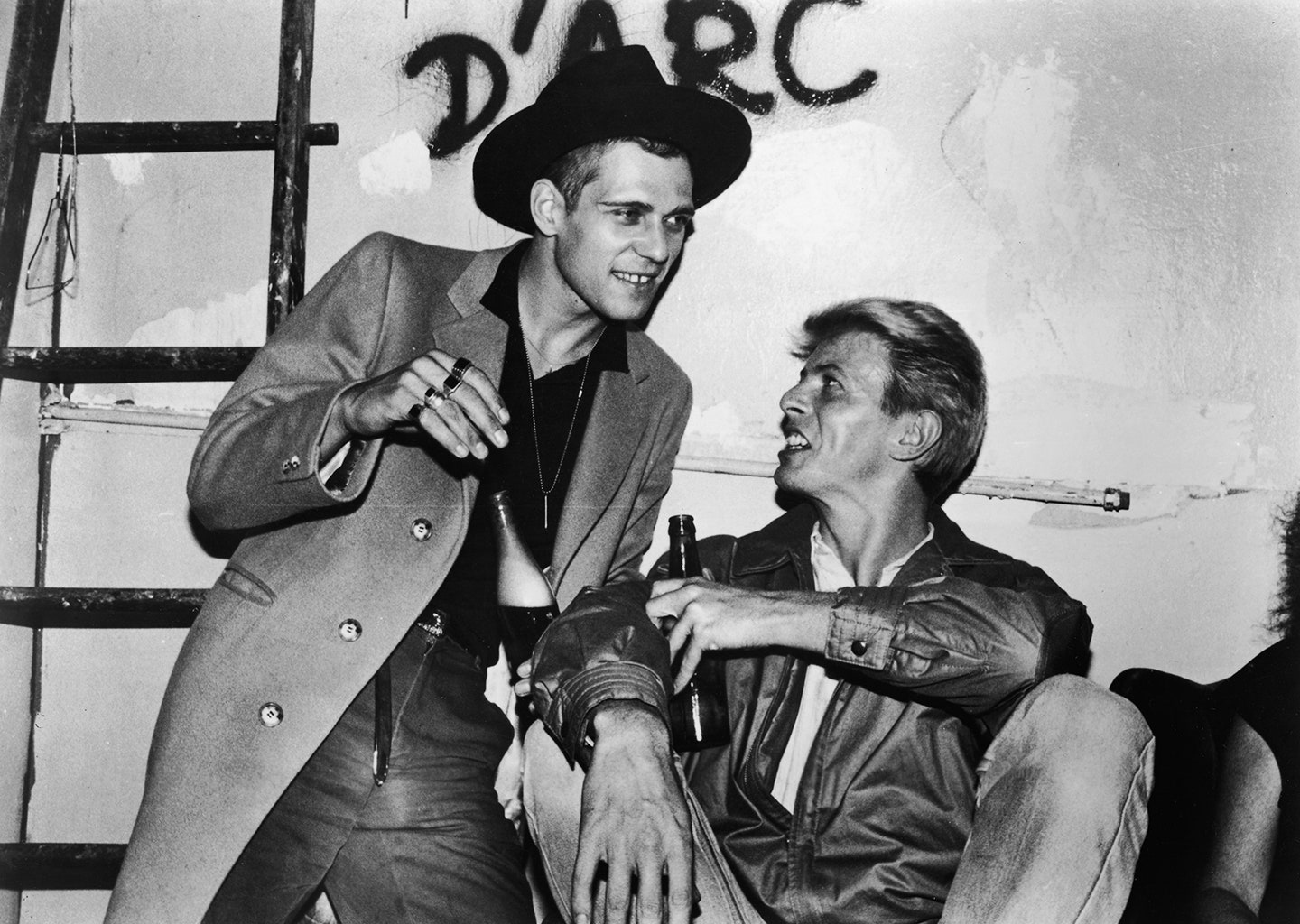

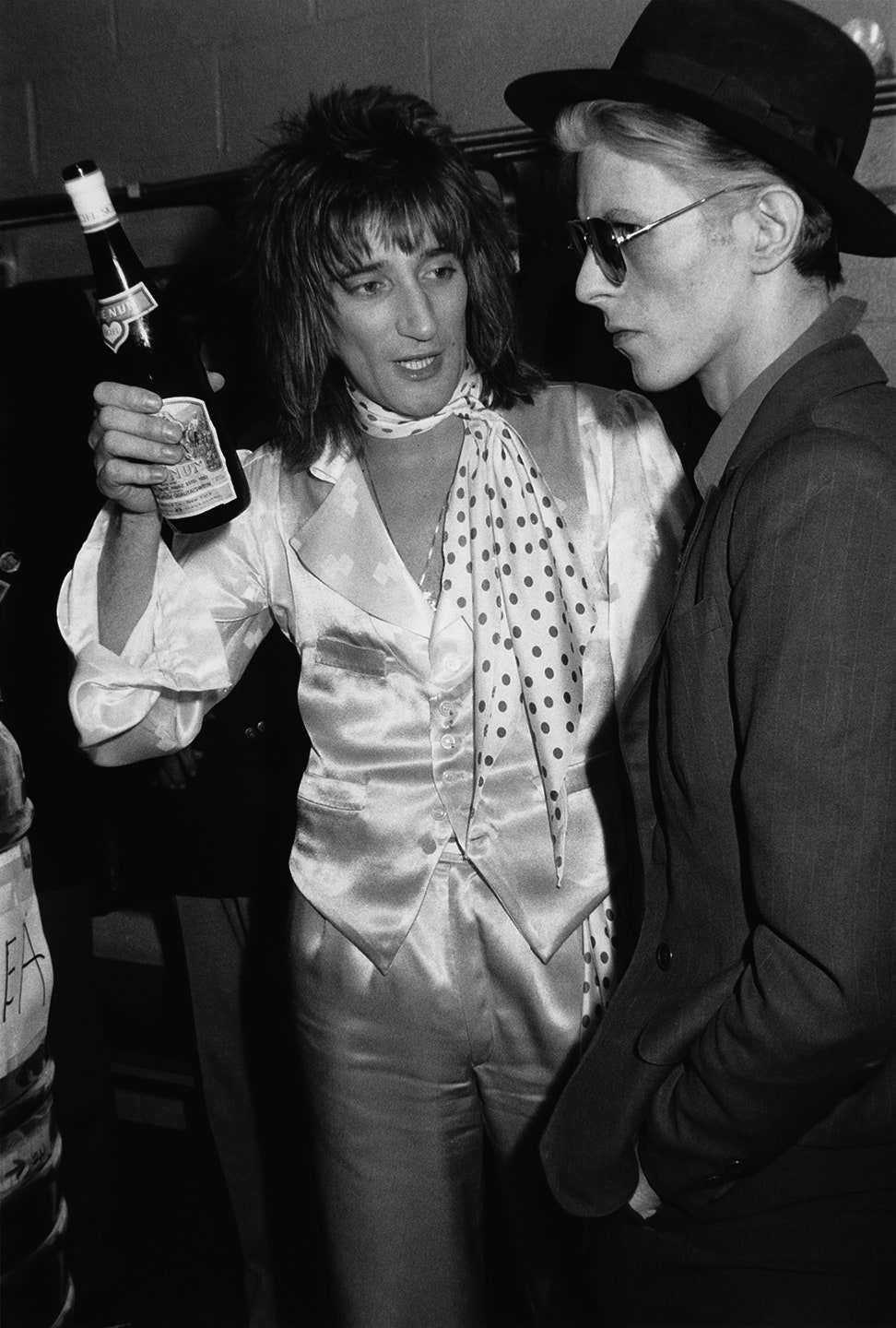

But he did act in other films, and for the most part, he was productively selective. For the ill-fated 1978 Just a Gigolo he took direction from the Swinging London icon of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, David Hemmings; even if the film was a bomb, the act of making it was an apt statement. In Nagisa Ôshima’s 1983 Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence—a tough, beautiful, and arguably under-seen movie, whose prisoner-of-war-camp setting made it a tough shoot for all its creators—Bowie channeled Terence Stamp’s incarnation of Billy Budd, among other things, to play an angelic captive enduring obsessive torment. He was understated and debonair playing a vampire in Tony Scott’s The Hunger that same year.

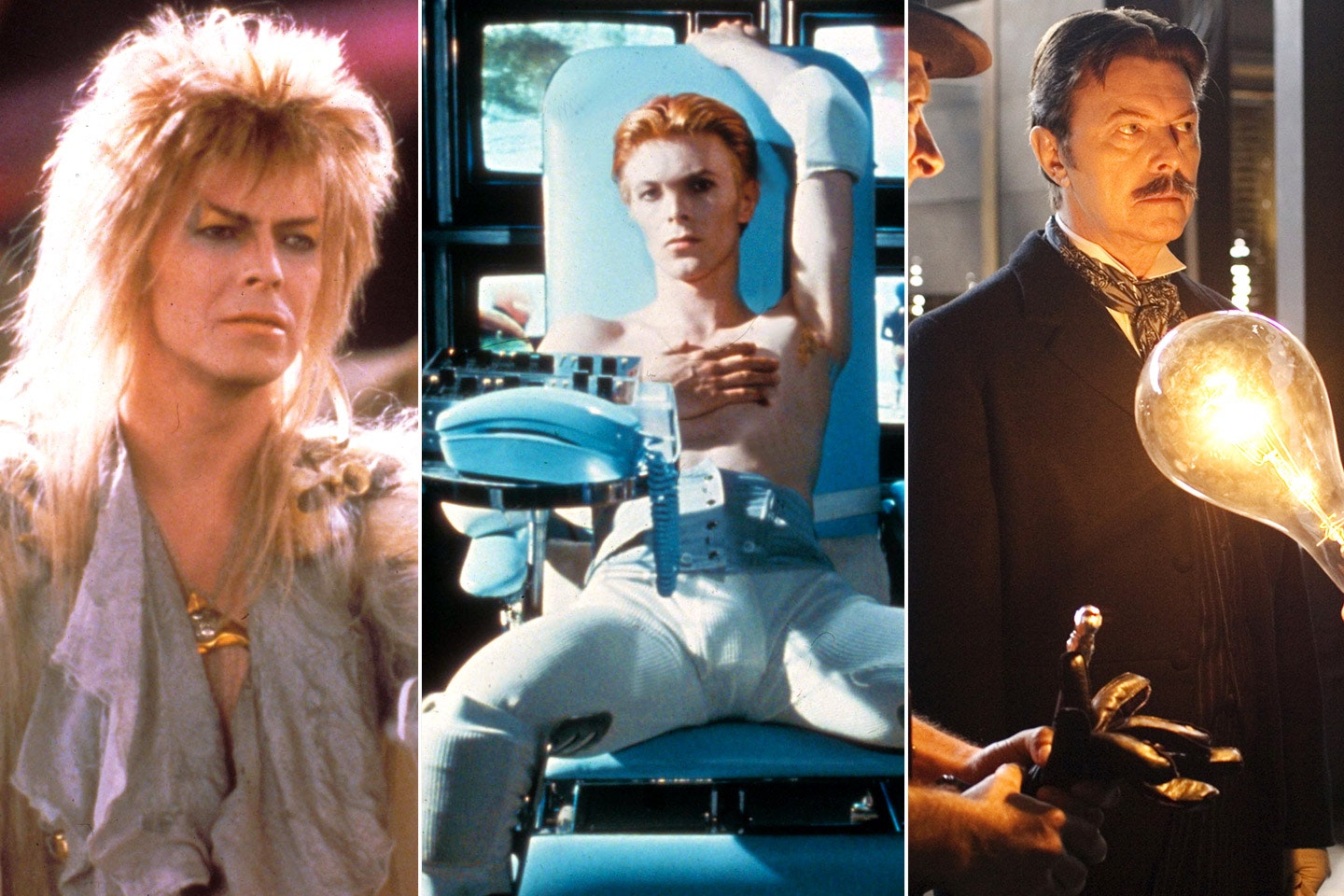

Mining the precedents available to a quintessentially British artist (one of the dozens of things he was), in Julien Temple’s 1986 musical of the not-quite-“Angry Young Man” novel Absolute Beginners, Bowie played Vendice Partners, a kind of gleefully sold-out ad man of Room at the Top ilk. Jim Henson’s Labyrinth cast him as a beguiling Goblin King, a malevolently seductive kind of Pied Piper, whose confrontation with the film’s heroine, Jennifer Connelly, provides her a chilling gateway out of childhood and into adolescence. Martin Scorsese, nearly as astute in his appreciation and manipulation of masks and personae as Bowie himself, cast the latter as a dry, deliberate Pontius Pilate in his 1988 The Last Temptation of Christ. All he had to do in David Lynch’s 1992 Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me to enhance that film’s unique atmosphere of fear and trembling was show up and shout and vanish into white noise.

In a career twist that was both jaw-droppingly odd and yet entirely right—this could be said to be true of all of Bowie’s career coups—he got to play Andy Warhol, beautifully, in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 Basquiat. In a sense Bowie here does “disappear” into his role. He wears a genuinely frightful silver wig, and goes to great pains to replicate Warhol’s flat speaking style. But there is an inescapable, deliberate, meta-textual dimension to the performance; it’s very definitely David Bowie playing Andy Warhol, making an artistic lesson out of the knowledge he had already dropped hard back on that Hunky Dory song in 1971.

His last major screen role was a short one, playing Nikola Tesla, the scientist-magician who invented alternating current, in Christopher Nolan’s 2006 The Prestige. By this time Bowie could be said to have defined his time as irrefutably as Tesla had; Nolan’s casting goes beyond mere drollery, and Bowie’s performance understands that, without ever becoming grandiose. Genius? I’d have to say yes.

My sentimental favorite of Bowie acting performances is in the 1984 long-form video “Jazzin’ for Blue Jean,” directed by Temple, with Bowie in the dual role of Vic, a nebbishy and not entirely likable paperhanger, and “Screamin’ Lord Byron,” a glammed-up, spaced-out rock star. Bragging to his “dream girl” that he’s acquainted with the music idol—whose songs and presence seem to send admirers into a kind of trance—Vic says, “Do you like that man? I know that man. We go back years. David Hockney introduced me. I write his lyrics.” Indeed.

After Vic suffers through some Ealing-style pratfalls and one of Bowie’s worst hairstyles, Bowie appears in the role of the icon—a Thomas Jerome Newton–esque wreck who turns into a stage performer of nearly obscene bluff assurance once his Cocteau-inspired makeup is applied. Bowie’s work is absolutely virtuoso in both modes, and the mini-movie’s ending is a very funny and entirely Bowie-esque commentary on the borders between idea and reality and expression. The song is pretty killer as Bowie singles go, too.