SALINAS, Puerto Rico ― It was a late August afternoon when the rain finally came, first as a drizzle that beaded on the plaza’s magnolia trees, then a downpour, darkening the dusty bricks and forming murky rivulets along the curbside.

Manases Vega was relieved by the prospect of daily showers and the ability to flush his toilet again.

This municipality of roughly 31,000 had been water rationing since June. Again. The first time came in 2015, following a prolonged drought. This summer, another parching dry spell drained the aquifer beneath this seaside enclave on Puerto Rico’s southeast coast to dangerously low levels.

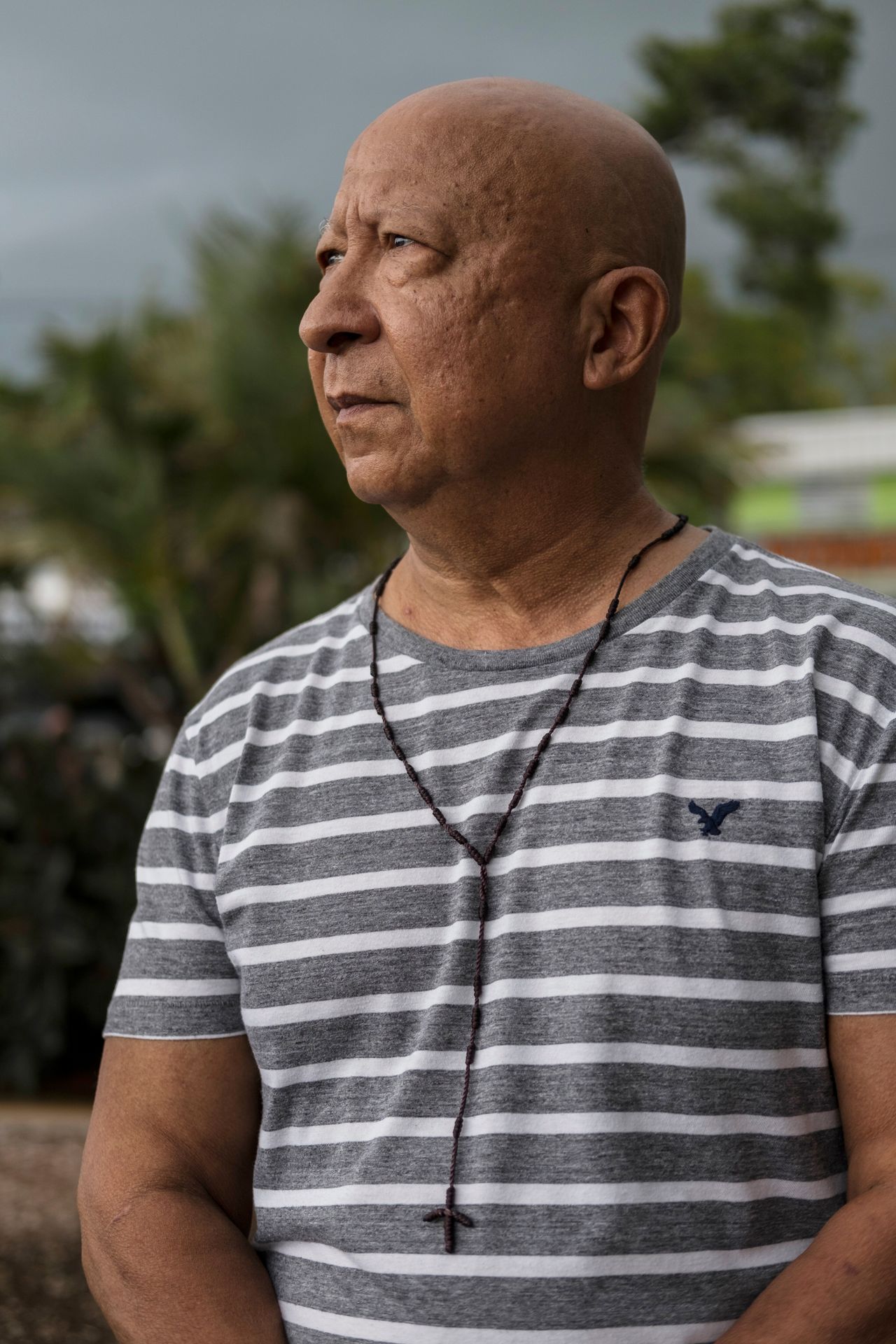

Yet the industries whose pollution Vega, 65, blames for triggering the mysterious respiratory illness that causes him to visit the emergency room to have his chest drained three days a week, kept sucking up water with an unquenchable thirst. Vega, meanwhile, lost water access every Tuesday and Thursday.

“They give the water to those big companies and we have no water,” Vega said, wheezing slightly. “It makes you very angry.”

This is a disaster that predates the 2017 hurricanes that exposed both the island’s deteriorating living standards and the lethal fragility of its water systems. For decades, this farming region turned industrial hub has tapped the aquifer that stretches more than 50 miles along the southern coast here. But stresses on the once-mighty South Coast basin are mounting. Real estate developers are paving over land that once absorbed rain and recharged the groundwater below. Pollution is contaminating the dwindling supply of freshwater. Agribusiness giants operate with near impunity as austerity renders overextended regulators ineffective.

All the while the planet is getting hotter, propelling Puerto Rico toward more catastrophic droughts and rising seas that gush saltwater into coastal aquifers.

“Where there is rain deficit, there is saline intrusion, especially in a coastal aquifer,” said José M. Rodríguez, a retired U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist who studied the aquifer for 31 years. “The problem of climate change will worsen the situation.”

Lax regulation, decaying public infrastructure and an ongoing debt crisis have left the troubled U.S. possession incapable of reliably delivering water to all its 3.2 million residents. Less than half the water the public utility treats makes it to ratepayers, and nearly all of that which does is of dubious quality, compelling only the most desperate Puerto Ricans to drink what flows from the tap. The most obvious solution is a total overhaul. But the colonial government, hounded by Wall Street creditors and in a state of chaotic quasi-bankruptcy, can barely keep the lights on, stoking fears that profiteers looking to buy up the indebted public power company may target water services next.

“This is an extremely serious issue,” Judith Enck, Puerto Rico’s former regional administrator at the Environmental Protection Agency for eight years under President Barack Obama. “Drinking water quality and drinking water quantity are at risk throughout the island.”

Thirst For Profits

The South Coast aquifer, stretching more than 50 miles from Ponce in the west to Patillas in the east, has been something of a quandary for as long as anyone can remember. Fed by streams that ran southward from the misty limestone mountain range that covers most of the island’s interior, the basin forms a fan delta. Alluvial soil, sediment rich with nutrients, accumulated atop the south-sloping bedrock, creating fertile farmland.

Puerto Rico’s South Coast was always drier than other parts of the island, with semi-arid conditions and roughly half the rainfall of its humid zones. But Puerto Rico’s landholders were committed to farming here. As the region became a hub of the island’s sugarcane industry, plantation workers started diverting mountain streams to irrigate fields as far back as the early 1800s. The systems grew more complex as demand for Puerto Rico’s cash crop soared and the United States invaded the former Spanish colony. By 1947, the sugarcane fields pulled an average 95 million gallons of water from the aquifer every day.

While the daily withdrawals eventually decreased, the extracting industries changed. As the United States sought to juxtapose its crown-jewel Caribbean colony with communist Cuba as an example of capitalist progress, the federal government lured mainland manufacturers here with lavish tax breaks and an American-educated workforce, sans the protections of U.S. labor laws. With accessible harbors a straight shot north from oil-rich Venezuela, the South Coast aquifer was reborn as a petrochemical and oil refining hub. But the oil embargo of the 1970s hit Puerto Rico hard, and that industrial development never yielded the riches it originally promised.

By the 1980s, the region still produced one-fourth of the island’s sugarcane. Today farms grow papayas, mangos and plantains. Yet between the neatly plowed fields that line Highway 3 sit fenced-off industrial facilities of agribusiness companies.

If farmers’ irrigation needs were fairly predictable after centuries of trial and error, environmentalists say it’s anyone’s guess how much water the companies use. At a Senate hearing this spring, Puerto Rican Department of Agriculture officials testified that at least half a dozen wells that serve industrial plants don’t even have meters, according to Victor Alvarado, a former Senate aide who now runs the environmental group Comité Diálogo Ambiental.

It’s unclear which sites to which regulators were referring. The Department of Agriculture did not respond to repeated requests by phone and email for comment.

The area around Salinas, however, is a who’s who of agrochemical behemoths, including Syngenta, DowDuPont spinoff Corteva, and Bayer-owned Monsanto. Just two of the companies named in this story responded to detailed questions sent over email. In a statement, Syngenta said its facility “draws water from a reservoir, supplied by a lake in Guayama, not from wells.”

“We voluntarily keep records of our water use from the reservoir, though it is not required,” spokesperson Ann Bryan said by email, adding that Syngenta’s facilities in nearby Juana Díaz draw from three wells.

Corteva said it faced shortages of well water during the rationing period, but continued to draw water from irrigation canals designated exclusively for agricultural uses.

“These were not included in the Government restrictions and we, along with our neighboring farmers, were able to use them,” Luis Colón, a spokesman for the company, said by email. “We report use, which is validated by personnel from the Department of Natural Resources of the Government of Puerto Rico.”

The industry received more than $526 million in subsidies and tax breaks between 2006 and 2015, according to a 2017 analysis of government records by the nonprofit watchdog Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, or CPI. During that same period, those multinationals took control of 14% of Puerto Rico’s public lands, including many of its most fertile farmlands at a moment when the island produces only a small fraction of its own food. That year, Monsanto owned 1,711 acres, while Dow AgroSciences and Mycogen Seeds controlled a combined 1,698 acres, the report found.

That sheer size, Alvarado said, makes it hard to keep track of these companies. In actuality, officials, he said, “have no idea how much water companies use.”

Splash Of Coal Water

Overall, industrial use has trended downward since former President Bill Clinton started phasing out federal tax breaks to manufacturers in 1996. In 1985, industrial plants sucked up 12% of water pulled daily from the South Coast aquifer, according to U.S. Geological Survey data. That figure fell to 9% by 2002.

But not all industries here were attracted by tax breaks. That same year, Virginia-based utility giant AES opened the island’s first (and only) coal-fired power plant in Guayama, a town just 15 minutes from Salinas. From the start, the plant’s cooling towers required 225,000 gallons of water per minute to circulate, according to EPA documents. Water usage totaled 5 million gallons per day, one study showed.

The water came, and still comes, from a variety of sources. Both the AES plant and the publicly-owned Aguirre Power Plant Complex that neighbors it used a mix that included seawater, stormwater and freshwater drawn from wells that tapped the aquifer. AES did not respond to a request for comment.

But the problem isn’t just consumption. Unlike the Aguirre plant, which burns heavily-polluting fuel oil, AES actually offered ― ironically ― comparatively cleaner, cheaper electricity from coal. But the plant also generated millions of tons of coal ash, waste that grew from a grayish-brown mound into a five-story mountain as disposal became challenging on a 3,515-square-mile island.

And with that growing mound of ash came concern about its contamination of the island’s groundwater.

A groundwater analysis released in January found contaminants such as selenium, lithium and molybdenum exceeded the EPA’s maximum threshold by four to 14 times. A report AES commissioned from the Boston-based engineering consultancy Haley Aldrich found the coal ash had “no impact on drinking water” and there was “no evidence of impact on human health or the environment.” The contamination, the report found, didn’t penetrate the deep part of the aquifer from which public wells draw water.

But coal ash contains dangerous heavy metals such as arsenic, hexavalent chromium, cadmium and mercury, and the link between coal ash and water contamination is only starting to emerge. The North Carolina Institute of Medicine concluded last year that more research is needed to determine the cumulative impacts of long-term exposure. Early signs are alarming. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry said some heavy metals and chemicals found in coal ash “can cause cancer after continued long-term ingestion and inhalation.” In March, the first national study to examine groundwater near coal-fired plants found that 242 of the 265 plants with monitoring data contained unsafe levels of one or more pollutants found in coal ash.

Between 2004 and 2014, Guayama ranked seventh out of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities with the highest incidence of cancer, according to Puerto Rico Cancer Registry data CPI cited in another report last year. Salinas placed sixth on the list.

Some here say windborne particles from the coal ash pile seem so ubiquitous they must be to blame, even if the contamination hasn’t spread deep into the drinking water.

Another form of pollution, meanwhile, had been seeping into the groundwater for decades. Nitrogen from poultry farms, pesticides and some leaking septic tanks in housing developments increased from a range of 0.9 to 5.9 milligrams per liter in 1967 to a range of 1.3 to 23.6 milligrams per liter in 2008, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study. Nitrate pollution is linked to various kinds of cancer, thyroid disease and respiratory problems in children.

“It’s a dire situation,” said Erik Olson, a water systems expert and senior director at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Yet real estate developers are burying even more septic tanks and paving over dirt that once absorbed much-needed water. Urbanizaciones, self-contained developments with retail and luxury housing, are on the rise, particularly in scenic areas like the South Coast, with its azure bays and views of the Caribbean Sea. Developers have long been accused of sidelining environmental impact concerns in a push to build.

In July, that looked poised to change. Former Gov. Ricardo Rosselló’s government was preparing to enact a new islandwide zoning policy that would have set uniform standards for considering the effects of pavement and developments on critical hydrological structures. But following Rosselló’s ouster in August after weeks of protests over his alleged corruption, talks have stalled.

“In the ’90s, you had almost unmitigated construction that not only destroyed many of the natural landscape characteristics but covered many of the sinkholes that are the main pathway for water to recharge aquifers,” said Raul Santiago, a researcher on environmental engineering at the Center for the New Economy, a San Juan-based think tank. “Today that problem is not as severe, mostly because of the economic downturn, so you don’t have as much construction; a silver lining from that crisis.”

‘Stretched Thin’

What flows from faucets in Puerto Rico is drinking water in name only.

The state-run Puerto Rico Aqueducts and Sewers Authority, or PRASA, has racked up fines for decades for failing to test the tap water for bacteria, chemicals and other contaminants, NPR reported last year. Between January 2016 and March 2018, 97% of Puerto Rico’s nearly 3.2 million residents were served by a drinking water system with at least one recent violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act’s lead and copper testing requirements. That’s nearly triple New Jersey, the second-place offender. PRASA did not respond to repeated requests by phone and email for comment.

The water-testing issue became particularly acute in the months after Hurricane María decimated the island’s infrastructure and caused the second-longest blackout in world history. Without access to running water and facing shortages of bottled water, Puerto Ricans drank from mountain springs and other natural sources contaminated with bacteria and other hazardous waste from Superfund sites. Nearly 75 people died of leptospirosis, waterborne bacteria spread by rats, in the first month after the storm. In December 2017, the Natural Resources Defense Council released leaked documents showing more than 2.3 million Puerto Rican residents “were served by water systems which drew at least one sample testing positive for total coliforms or E. coli.”

It’s partly a personnel problem. Between 2012 and 2017, the island’s Department of Health employed just one full-time chemist in the tap and bottled water testing laboratory, according to a source with direct knowledge of the staffing who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal. Since the hurricane, federal officials from the EPA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention increased the number of scientists testing water on the island. But the Department of Health lacks the equipment and authority to test aquifers for the kinds of chemicals and pollutants agribusiness plants commonly discharge, the source said.

The austerity federal authorities imposed on Puerto Rico in 2016 when the island collapsed under its $74 billion debt load also forced the territorial government to merge the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources with the Environmental Quality Board, the Solid Waste Management Authority and the National Parks Program. The Rosselló administration estimated the new super agency would save more than $5 million in the first year and over $50 million by 2023, the trade publication Caribbean Business reported. But it forced an agency whose traditional responsibilities, such as coastal management and flood protection, had grown more daunting to now also consider public health issues with a budget that was already “severely underfunded,” Santiago said.

“DNER has always been stretched thin,” he said. “Now it’s forced to reorganize itself in an even less proactive way.”

The savings from merging the agencies are set to be passed on in the form of repayments to the so-called Wall Street vulture funds that bought up Puerto Rico’s bond market debt on the cheap over the past decade. But the most obvious place to reinvest the money would be in overhauling PRASA’s water delivery system. The water utility last year reported losing nearly 50% of the potable water it produces to leaks and spills.

“That means water is extracted at an even quicker pace than it should be,” Santiago said, calling it “the most urgent issue in water management on the island going forward.”

‘Shock’ To The System

Post-hurricane Puerto Rico has become, in many ways, a poster child for what writer Naomi Klein dubbed “shock doctrine,” when so-called disaster capitalists swoop in to buy up parts of the distressed public sector in hopes of profiting off services the government once provided to taxpayers.

Even before the storm shredded the island’s aging power lines, the federally required spending cuts were propelling an effort to sell off the electrical utility. Some now fear PRASA could be next.

Private water systems serve just 12% of the United States, a study from the University of North Carolina found. But large privately owned water systems charged 59% more than their publicly owned counterparts, according to a 2016 Food & Water Watch survey of the 500 largest community water systems in the country.

In debt-strapped municipalities, the threat of privatization looms large. Detroit started taking bids to sell off its water utility in 2014, a year after the city declared bankruptcy. Motor City residents have felt the pinch. Last year, officials threatened to shut off water to nearly 17,500 households that were behind on bills as part of what left-wing think tank Centre for Research on Globalization described as an effort to prime the utility for sale to profiteers.

Baltimore, racked by its own budget problems, voted in a referendum last November to become the first U.S. city to ban water privatization. Pittsburgh’s city council was considering a similar measure, Reuters reported.

It’s been tried before in Puerto Rico. PRASA contracted out the management of its water services during a wave of privatization in the mid-1990s under then-Gov. Pedro Rosselló. But the effects, as detailed in a 2007 report from the Puerto Rico comptroller’s office, were disastrous, with rapidly deteriorating service and soaring rates. The government declined to renew the contract with French utility giant Veolia in 2001. Another attempt to privatize PRASA in the early 2000s ended in contract disputes.

Enck called PRASA “one of the worst-run public water authorities in the country,” but said a better way to fix it would be to devolve control to communities and stack the utility’s board with scientists and local residents “who have a stake in wanting clean water.” There are examples of this working. In Guayabota, a town northeast of Guayama, a large non-PRASA system installed solar panels to provide renewable energy and has dramatically improved access and quality, according to an 85-page report out this month from the nonprofit U.S. Water Alliance.

“It can’t be business as usual,” she said. “PRASA needs to be completely reworked and democratically controlled at the local level.”

But in Puerto Rico, drinking water has functionally been a private service for decades as anyone with enough money bought bottled water from the supermarket anyway, Vega said.

“When I was young in Salinas, I was very poor, and I had to drink whatever we had,” he said. “But I started drinking bottled water when I got married about 30 years ago, and I always bottled water now. I don’t trust the water.”

That alone is setting the stage for another looming crisis as single-use plastic water bottles pile up in landfills, said Enck, who recently launched a nonprofit called Beyond Plastics at Bennington College in Vermont.

“More and more people are spending their limited money buying single use plastic water bottles,” she said. “People are probably spending more on bottled water than their PRASA bill in some instances. Of course, there’s no comprehensive recycling program for all of those plastic bottles.”

Last February, on the opposite side of the island from Vega, PRASA instituted water rationing in seven municipalities served by the Guajataca reservoir, a manmade lake nestled in Karst Country foothills of northwestern Puerto Rico.

The rationing in Salinas ended by September. But nowhere seems immune to the threat. Earlier this month, a private contractor hired to repair water lines cut off water service to some of the most populous parts of the San Juan metropolitan area.

As Vega’s illness worsens ― he suspects the windborne coal ash dust that blows over from neighboring Guayama inflames it ― the retired high school art teacher is considering abandoning his hometown. His wife has liver problems as well, and his brothers, one in Maryland, the other in Texas, are encouraging him to come to the mainland.

Despite everything, it’s not an easy decision. He grew up here. He taught generations of kids here. He was the renaissance man of Salinas, renowned as a great painter of landscapes and vibrant still lifes and a self-described “master pole vaulter” who once exercised daily on the beach.

“I have always lived here,” he said. “But it’s not easy to live here in Salinas anymore.”