With their swooping curves and monumental scale, Brasília's audacious public buildings will likely stand as the greatest legacy of Oscar Niemeyer, who will soon be 99 years old. But during a career now spanning more than seven decades, the great Brazilian architect has also produced many residential designs, none more remarkable than that for a house in Santa Barbara, California. If it had been built, the house would have joined the United Nations Headquarters and a Santa Monica residence (see Architectural Digest, May 2005) as the only fully realized Niemeyer projects in the United States. What's more, it clearly would have become one of America's most significant 20th-century houses, as iconic in its own way as Wright's Fallingwater or Neutra's Lovell House.

In 1947, nearly a decade before Brasília and around the time he began collaborating with Le Corbusier on the United Nations building, Niemeyer was contacted by the American industrialist Burton G. Tremaine, Sr., and his wife, Emily Hall Tremaine. Important collectors of modern art who eventually amassed 400- plus works, which The New York Times described as "a stellar assemblage that breathes the spirit of 20th-century modernism," the Tremaines were also keenly interested in contemporary architecture. During the late 1940s alone, they hired Frank Lloyd Wright, Buckminster Fuller and Philip Johnson for a variety of projects, only some of which came to fruition.

From Niemeyer, whose work they greatly admired, the Tremaines commissioned plans for a house to be built on a low, oceanside bluff in Montecito. Owned by Emily Tremaine, the site had once belonged to Robert Louis Stevenson's stepdaughter and was thick with cypress and eucalyptus trees and with the palms, ginger, jasmine and other exotics she had transplanted there from the author's beloved Samoa. Without ever meeting the Tremaines or seeing the site—his Communist Party membership made travel to the United States problematic—Niemeyer produced a model and seven conceptual drawings in 1948. His friend and frequent collaborator, the Brazilian landscape architect and painter Roberto Burle Marx, contributed a conceptual garden plan of colorful, abstract shapes reminiscent of Miró and Jean Arp.

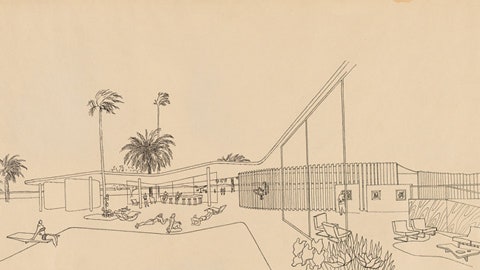

In Niemeyer's plan, Bauhaus meets the Girl from Ipanema in a surprising juxtaposition of two distinct components—an airy first floor whose free-flowing curves echo the wavy, lyric beauty of Burle Marx's garden design, and a structurally independent, highly rectilinear second floor in the form of a long block offset to the rear and raised on stilts. This arrangement, according to Niemeyer's notes, took "maximum advantage of the marvelous view offered by the Pacific Ocean," avoided shutting off the entrance from the sea and captured ocean breezes and light in the boxlike second floor, a functional space given over to the master suite and guest rooms.

The soul of the house, however, resides in its first floor, a glass-walled living/dining pavilion surrounded by a series of enclosed or open porches that flow into the garden and pool area. Dedicated to entertaining and relaxing, the floor also includes an elevated music area, "which will permit dancing around the bar and the swimming pool during parties." One of Niemeyer's more playful drawings illustrates just such a gathering, at which bikini-clad women lounge around the pool while other guests gather at a bar or admire some of the sculpture and paintings that were "planned not as independent elements but as integrating [sic] parts of the whole—enriching and completing it." You can almost taste the caipirinhas and hear the gentle sway of Brazilian music.

By all accounts, the Tremaines' pleasure with Niemeyer's and Burle Marx's work was outweighed only by the projected cost of building such a lavish house. In Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp, author Kathleen L. Housley writes, "Even Burton, who loved parties, good times, boating, and everything else that went along with those activities, found the plans too ambitious." According to Housley, though the Tremaines eventually declined to proceed with construction, Emily felt the plans should be published so they could be seen by, and influence, other architects. In 1949 the plans appeared in two magazine articles and were included in a New York Museum of Modern Art exhibition, "From Le Corbusier to Niemeyer, 1929–49," curated by Philip Johnson. In 1953 the Tremaines gave them to the museum, where they remain.

Any regrets Niemeyer had about the house's not being built must have immediately been supplanted by the hugely important commissions then on his drafting board, in particular the United Nations buildings. But in his written 1988 Pritzker Prize acceptance speech, in which he talked about his profession, Niemeyer could well have been referring to the Tremaine project. "A concern for beauty," he wrote, "a zest for fantasy, and an ever-present element of surprise bear witness that today's architecture is not a minor craft bound to straightedge rules."