You can find all the code for this chapter here

For all the power of modern computers to perform huge sums at lightning speed, the average developer rarely uses any mathematics to do their job. But not today! Today we'll use mathematics to solve a real problem. And not boring mathematics - we're going to use trigonometry and vectors and all sorts of stuff that you always said you'd never have to use after highschool.

You want to make an SVG of a clock. Not a digital clock - no, that

would be easy - an analogue clock, with hands. You're not looking for anything

fancy, just a nice function that takes a Time from the time package and

spits out an SVG of a clock with all the hands - hour, minute and second -

pointing in the right direction. How hard can that be?

First we're going to need an SVG of a clock for us to play with. SVGs are a fantastic image format to manipulate programmatically because they're written as a series of shapes, described in XML. So this clock:

is described like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN" "https://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd">

<svg xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

width="100%"

height="100%"

viewBox="0 0 300 300"

version="2.0">

<!-- bezel -->

<circle cx="150" cy="150" r="100" style="fill:#fff;stroke:#000;stroke-width:5px;"/>

<!-- hour hand -->

<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="114.150000" y2="132.260000"

style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:7px;"/>

<!-- minute hand -->

<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="101.290000" y2="99.730000"

style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:7px;"/>

<!-- second hand -->

<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="77.190000" y2="202.900000"

style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/>

</svg>It's a circle with three lines, each of the lines starting in the middle of the circle (x=150, y=150), and ending some distance away.

So what we're going to do is reconstruct the above somehow, but change the lines so they point in the appropriate directions for a given time.

Before we get too stuck in, lets think about an acceptance test.

Wait, you don't know what an acceptance test is yet. Look, let me try to explain.

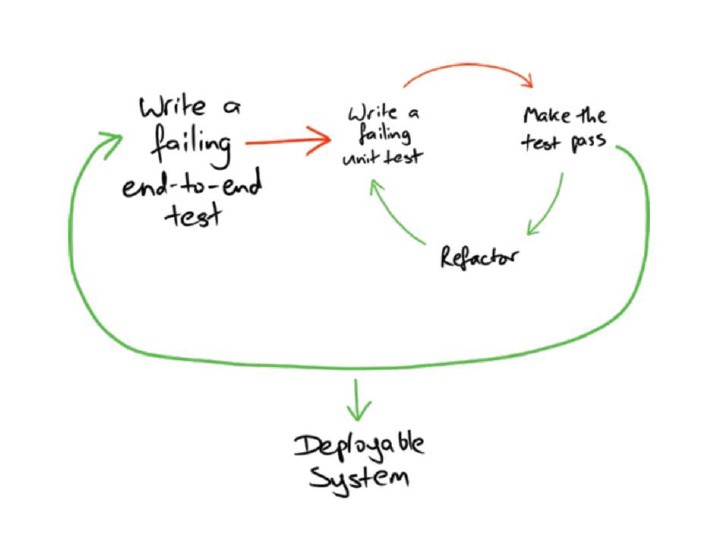

Let me ask you: what does winning look like? How do we know we've finished work? TDD provides a good way of knowing when you've finished: when the test passes. Sometimes it's nice - actually, almost all of the time it's nice - to write a test that tells you when you've finished writing the whole usable feature. Not just a test that tells you that a particular function is working in the way you expect, but a test that tells you that the whole thing you're trying to achieve - the 'feature' - is complete.

These tests are sometimes called 'acceptance tests', sometimes called 'feature test'. The idea is that you write a really high level test to describe what you're trying to achieve - a user clicks a button on a website, and they see a complete list of the Pokémon they've caught, for instance. When we've written that test, we can then write more tests - unit tests - that build towards a working system that will pass the acceptance test. So for our example these tests might be about rendering a webpage with a button, testing route handlers on a web server, performing database look ups, etc. All of these things will be TDD'd, and all of them will go towards making the original acceptance test pass.

Something like this classic picture by Nat Pryce and Steve Freeman

Anyway, let's try and write that acceptance test - the one that will let us know when we're done.

We've got an example clock, so let's think about what the important parameters are going to be.

<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="114.150000" y2="132.260000"

style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:7px;"/>

The centre of the clock (the attributes x1 and y1 for this line) is the same

for each hand of the clock. The numbers that need to change for each hand of the

clock - the parameters to whatever builds the SVG - are the x2 and y2

attributes. We'll need an X and a Y for each of the hands of the clock.

I could think about more parameters - the radius of the clockface circle, the size of the SVG, the colours of the hands, their shape, etc... but it's better to start off by solving a simple, concrete problem with a simple, concrete solution, and then to start adding parameters to make it generalised.

So we'll say that

- every clock has a centre of (150, 150)

- the hour hand is 50 long

- the minute hand is 80 long

- the second hand is 90 long.

A thing to note about SVGs: the origin - point (0,0) - is at the top left hand corner, not the bottom left as we might expect. It'll be important to remember this when we're working out where what numbers to plug in to our lines.

Finally, I'm not deciding how to construct the SVG - we could use a template

from the text/template package, or we could just send bytes into

a bytes.Buffer or a writer. But we know we'll need those numbers, so let's

focus on testing something that creates them.

So my first test looks like this:

package clockface_test

import (

"testing"

"time"

)

func TestSecondHandAtMidnight(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, time.UTC)

want := clockface.Point{X: 150, Y: 150 - 90}

got := clockface.SecondHand(tm)

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Got %v, wanted %v", got, want)

}

}Remember how SVGs plot their coordinates from the top left hand corner? To place the second hand at midnight we expect that it hasn't moved from the centre of the clockface on the X axis - still 150 - and the Y axis is the length of the hand 'up' from the centre; 150 minus 90.

This drives out the expected failures around the missing functions and types:

--- FAIL: TestSecondHandAtMidnight (0.00s)

./clockface_test.go:13:10: undefined: clockface.Point

./clockface_test.go:14:9: undefined: clockface.SecondHand

So a Point where the tip of the second hand should go, and a function to get it.

Let's implement those types to get the code to compile

package clockface

import "time"

// A Point represents a two dimensional Cartesian coordinate

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

// SecondHand is the unit vector of the second hand of an analogue clock at time `t`

// represented as a Point.

func SecondHand(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{}

}and now we get:

--- FAIL: TestSecondHandAtMidnight (0.00s)

clockface_test.go:17: Got {0 0}, wanted {150 60}

FAIL

exit status 1

FAIL github.com/gypsydave5/learn-go-with-tests/math/v1/clockface 0.006s

When we get the expected failure, we can fill in the return value of SecondHand:

// SecondHand is the unit vector of the second hand of an analogue clock at time `t`

// represented as a Point.

func SecondHand(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{150, 60}

}Behold, a passing test.

PASS

ok clockface 0.006s

No need to refactor yet - there's barely enough code!

We probably need to do some work here that doesn't just involve returning a clock that shows midnight for every time...

func TestSecondHandAt30Seconds(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 30, 0, time.UTC)

want := clockface.Point{X: 150, Y: 150 + 90}

got := clockface.SecondHand(tm)

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Got %v, wanted %v", got, want)

}

}Same idea, but now the second hand is pointing downwards so we add the length to the Y axis.

This will compile... but how do we make it pass?

How are we going to solve this problem?

Every minute the second hand goes through the same 60 states, pointing in 60 different directions. When it's 0 seconds it points to the top of the clockface, when it's 30 seconds it points to the bottom of the clockface. Easy enough.

So if I wanted to think about in what direction the second hand was pointing at,

say, 37 seconds, I'd want the angle between 12 o'clock and 37/60ths around the

circle. In degrees this is (360 / 60 ) * 37 = 222, but it's easier just to

remember that it's 37/60 of a complete rotation.

But the angle is only half the story; we need to know the X and Y coordinate that the tip of the second hand is pointing at. How can we work that out?

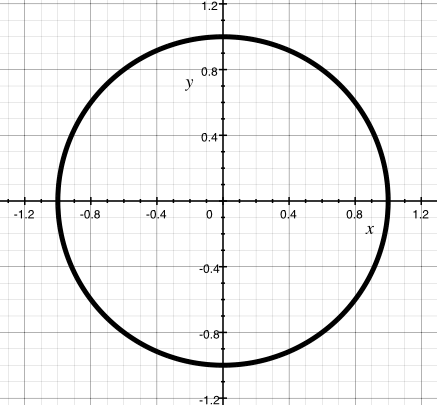

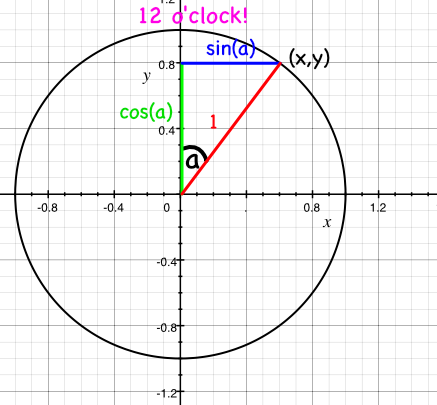

Imagine a circle with a radius of 1 drawn around the origin - the coordinate 0, 0.

This is called the 'unit circle' because... well, the radius is 1 unit!

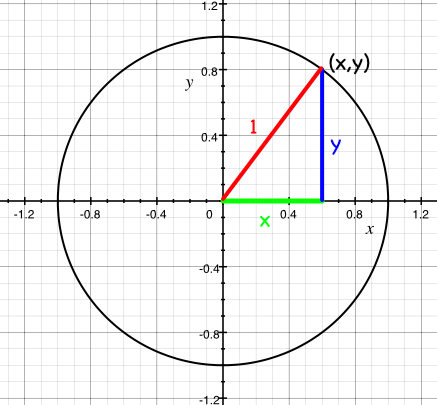

The circumference of the circle is made of points on the grid - more coordinates. The x and y components of each of these coordinates form a triangle, the hypotenuse of which is always 1 (i.e. the radius of the circle).

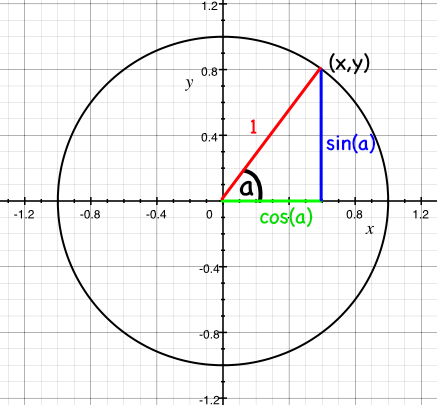

Now, trigonometry will let us work out the lengths of X and Y for each triangle if we know the angle they make with the origin. The X coordinate will be cos(a), and the Y coordinate will be sin(a), where a is the angle made between the line and the (positive) x axis.

(If you don't believe this, go and look at Wikipedia...)

One final twist - because we want to measure the angle from 12 o'clock rather than from the X axis (3 o'clock), we need to swap the axis around; now x = sin(a) and y = cos(a).

So now we know how to get the angle of the second hand (1/60th of a circle for

each second) and the X and Y coordinates. We'll need functions for both sin

and cos.

Happily the Go math package has both, with one small snag we'll need to get

our heads around; if we look at the description of math.Cos:

Cos returns the cosine of the radian argument x.

It wants the angle to be in radians. So what's a radian? Instead of defining the full turn of a circle to be made up of 360 degrees, we define a full turn as being 2π radians. There are good reasons to do this that we won't go in to.1

Now that we've done some reading, some learning and some thinking, we can write our next test.

All this maths is hard and confusing. I'm not confident I understand what's going on - so let's write a test! We don't need to solve the whole problem in one go - let's start off with working out the correct angle, in radians, for the second hand at a particular time.

I'm going to write these tests within the clockface package; they may never

get exported, and they may get deleted (or moved) once I have a better grip on

what's going on.

I'm also going to comment out the acceptance test that I was working on while I'm working on these tests - I don't want to get distracted by that test while I'm getting this one to pass.

package clockface

import (

"math"

"testing"

"time"

)

func TestSecondsInRadians(t *testing.T) {

thirtySeconds := time.Date(312, time.October, 28, 0, 0, 30, 0, time.UTC)

want := math.Pi

got := secondsInRadians(thirtySeconds)

if want != got {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", want, got)

}

}Here we're testing that 30 seconds past the minute should put the

second hand at halfway around the clock. And it's our first use of

the math package! If a full turn of a circle is 2π radians, we

know that halfway round should just be π radians. math.Pi provides

us with a value for π.

./clockface_test.go:12:9: undefined: secondsInRadians

func secondsInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return 0

}clockface_test.go:15: Wanted 3.141592653589793 radians, but got 0

func secondsInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return math.Pi

}PASS

ok clockface 0.011s

Nothing needs refactoring yet

Now we can extend the test to cover a few more scenarios. I'm going to skip forward a bit and show some already refactored test code - it should be clear enough how I got where I want to.

func TestSecondsInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(0, 0, 30), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 0), 0},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 45), (math.Pi / 2) * 3},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 7), (math.Pi / 30) * 7},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := secondsInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}I added a couple of helper functions to make writing this table based test

a little less tedious. testName converts a time into a digital watch

format (HH:MM:SS), and simpleTime constructs a time.Time using only the

parts we actually care about (again, hours, minutes and seconds).2 Here

they are:

func simpleTime(hours, minutes, seconds int) time.Time {

return time.Date(312, time.October, 28, hours, minutes, seconds, 0, time.UTC)

}

func testName(t time.Time) string {

return t.Format("15:04:05")

}These two functions should help make these tests (and future tests) a little easier to write and maintain.

This gives us some nice test output:

clockface_test.go:24: Wanted 0 radians, but got 3.141592653589793

clockface_test.go:24: Wanted 4.71238898038469 radians, but got 3.141592653589793

Time to implement all of that maths stuff we were talking about above:

func secondsInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return float64(t.Second()) * (math.Pi / 30)

}One second is (2π / 60) radians... cancel out the 2 and we get π/30 radians.

Multiply that by the number of seconds (as a float64) and we should now have

all the tests passing...

clockface_test.go:24: Wanted 3.141592653589793 radians, but got 3.1415926535897936

Wait, what?

Floating point arithmetic is notoriously inaccurate. Computers

can only really handle integers, and rational numbers to some extent. Decimal

numbers start to become inaccurate, especially when we factor them up and down

as we are in the secondsInRadians function. By dividing math.Pi by 30 and

then by multiplying it by 30 we've ended up with a number that's no longer the

same as math.Pi.

There are two ways around this:

- Live with it

- Refactor our function by refactoring our equation

Now (1) may not seem all that appealing, but it's often the only way to make floating point equality work. Being inaccurate by some infinitesimal fraction is frankly not going to matter for the purposes of drawing a clockface, so we could write a function that defines a 'close enough' equality for our angles. But there's a simple way we can get the accuracy back: we rearrange the equation so that we're no longer dividing down and then multiplying up. We can do it all by just dividing.

So instead of

numberOfSeconds * π / 30

we can write

π / (30 / numberOfSeconds)

which is equivalent.

In Go:

func secondsInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return (math.Pi / (30 / (float64(t.Second()))))

}And we get a pass.

PASS

ok clockface 0.005s

It should all look something like this.

Computers often don't like dividing by zero because infinity is a bit strange.

In Go if you try to explicitly divide by zero you will get a compilation error.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(10.0 / 0.0) // fails to compile

}Obviously the compiler can't always predict that you'll divide by zero, such as our t.Second()

Try this

func main() {

fmt.Println(10.0 / zero())

}

func zero() float64 {

return 0.0

}It will print +Inf (infinity). Dividing by +Inf seems to result in zero and we can see this with the following:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(secondsinradians())

}

func zero() float64 {

return 0.0

}

func secondsinradians() float64 {

return (math.Pi / (30 / (float64(zero()))))

}So we've got the first part covered here - we know what angle the second hand will be pointing at in radians. Now we need to work out the coordinates.

Again, let's keep this as simple as possible and only work with the unit circle; the circle with a radius of 1. This means that our hands will all have a length of one but, on the bright side, it means that the maths will be easy for us to swallow.

func TestSecondHandVector(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(0, 0, 30), Point{0, -1}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := secondHandPoint(c.time)

if got != c.point {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}./clockface_test.go:40:11: undefined: secondHandPoint

func secondHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{}

}clockface_test.go:42: Wanted {0 -1} Point, but got {0 0}

func secondHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{0, -1}

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

func TestSecondHandPoint(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(0, 0, 30), Point{0, -1}},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 45), Point{-1, 0}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := secondHandPoint(c.time)

if got != c.point {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}clockface_test.go:43: Wanted {-1 0} Point, but got {0 -1}

Remember our unit circle picture?

Also recall that we want to measure the angle from 12 o'clock which is the Y axis instead of from the X axis which we would like measuring the angle between the second hand and 3 o'clock.

We now want the equation that produces X and Y. Let's write it into seconds:

func secondHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

angle := secondsInRadians(t)

x := math.Sin(angle)

y := math.Cos(angle)

return Point{x, y}

}Now we get

clockface_test.go:43: Wanted {0 -1} Point, but got {1.2246467991473515e-16 -1}

clockface_test.go:43: Wanted {-1 0} Point, but got {-1 -1.8369701987210272e-16}

Wait, what (again)? Looks like we've been cursed by the floats once more - both of those unexpected numbers are infinitesimal - way down at the 16th decimal place. So again we can either choose to try to increase precision, or to just say that they're roughly equal and get on with our lives.

One option to increase the accuracy of these angles would be to use the rational

type Rat from the math/big package. But given the objective is to draw an

SVG and not land on the moon landings I think we can live with a bit of

fuzziness.

func TestSecondHandPoint(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(0, 0, 30), Point{0, -1}},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 45), Point{-1, 0}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := secondHandPoint(c.time)

if !roughlyEqualPoint(got, c.point) {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}

func roughlyEqualFloat64(a, b float64) bool {

const equalityThreshold = 1e-7

return math.Abs(a-b) < equalityThreshold

}

func roughlyEqualPoint(a, b Point) bool {

return roughlyEqualFloat64(a.X, b.X) &&

roughlyEqualFloat64(a.Y, b.Y)

}We've defined two functions to define approximate equality between two

Points - they'll work if the X and Y elements are within 0.0000001 of each

other. That's still pretty accurate.

And now we get:

PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

I'm still pretty happy with this.

Here's what it looks like now

Well, saying new isn't entirely accurate - really what we can do now is get that acceptance test passing! Let's remind ourselves of what it looks like:

func TestSecondHandAt30Seconds(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 30, 0, time.UTC)

want := clockface.Point{X: 150, Y: 150 + 90}

got := clockface.SecondHand(tm)

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Got %v, wanted %v", got, want)

}

}clockface_acceptance_test.go:28: Got {150 60}, wanted {150 240}

We need to do three things to convert our unit vector into a point on the SVG:

- Scale it to the length of the hand

- Flip it over the X axis because to account for the SVG having an origin in the top left hand corner

- Translate it to the right position (so that it's coming from an origin of (150,150))

Fun times!

// SecondHand is the unit vector of the second hand of an analogue clock at time `t`

// represented as a Point.

func SecondHand(t time.Time) Point {

p := secondHandPoint(t)

p = Point{p.X * 90, p.Y * 90} // scale

p = Point{p.X, -p.Y} // flip

p = Point{p.X + 150, p.Y + 150} // translate

return p

}Scale, flip, and translate in exactly that order. Hooray maths!

PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

There's a few magic numbers here that should get pulled out as constants, so let's do that

const secondHandLength = 90

const clockCentreX = 150

const clockCentreY = 150

// SecondHand is the unit vector of the second hand of an analogue clock at time `t`

// represented as a Point.

func SecondHand(t time.Time) Point {

p := secondHandPoint(t)

p = Point{p.X * secondHandLength, p.Y * secondHandLength}

p = Point{p.X, -p.Y}

p = Point{p.X + clockCentreX, p.Y + clockCentreY} //translate

return p

}Well... the second hand anyway...

Let's do this thing - because there's nothing worse than not delivering some value when it's just sitting there waiting to get out into the world to dazzle people. Let's draw a second hand!

We're going to stick a new directory under our main clockface package

directory, called (confusingly), clockface. In there we'll put the main

package that will create the binary that will build an SVG:

|-- clockface

| |-- main.go

|-- clockface.go

|-- clockface_acceptance_test.go

|-- clockface_test.go

Inside main.go, you'll start with this code but change the import for the

clockface package to point at your own version:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"os"

"time"

"github.com/quii/learn-go-with-tests/math/clockface" // REPLACE THIS!

)

func main() {

t := time.Now()

sh := clockface.SecondHand(t)

io.WriteString(os.Stdout, svgStart)

io.WriteString(os.Stdout, bezel)

io.WriteString(os.Stdout, secondHandTag(sh))

io.WriteString(os.Stdout, svgEnd)

}

func secondHandTag(p clockface.Point) string {

return fmt.Sprintf(`<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%f" y2="%f" style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}

const svgStart = `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN" "https://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd">

<svg xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

width="100%"

height="100%"

viewBox="0 0 300 300"

version="2.0">`

const bezel = `<circle cx="150" cy="150" r="100" style="fill:#fff;stroke:#000;stroke-width:5px;"/>`

const svgEnd = `</svg>`Oh boy am I not trying to win any prizes for beautiful code with this mess -

but it does the job. It's writing an SVG out to os.Stdout - one string at

a time.

If we build this

go build

and run it, sending the output into a file

./clockface > clock.svg

We should see something like

And this is how the code looks.

This stinks. Well, it doesn't quite stink stink, but I'm not happy about it.

- That whole

SecondHandfunction is super tied to being an SVG... without mentioning SVGs or actually producing an SVG... - ... while at the same time I'm not testing any of my SVG code.

Yeah, I guess I screwed up. This feels wrong. Let's try to recover with a more SVG-centric test.

What are our options? Well, we could try testing that the characters spewing out

of the SVGWriter contain things that look like the sort of SVG tag we're

expecting for a particular time. For instance:

func TestSVGWriterAtMidnight(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, time.UTC)

var b strings.Builder

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, tm)

got := b.String()

want := `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="150" y2="60"`

if !strings.Contains(got, want) {

t.Errorf("Expected to find the second hand %v, in the SVG output %v", want, got)

}

}But is this really an improvement?

Not only will it still pass if I don't produce a valid SVG (as it's only testing that a string appears in the output), but it will also fail if I make the smallest, unimportant change to that string - if I add an extra space between the attributes, for instance.

The biggest smell is that I'm testing a data structure - XML - by looking at its representation as a series of characters - as a string. This is never, ever a good idea as it produces problems just like the ones I outline above: a test that's both too fragile and not sensitive enough. A test that's testing the wrong thing!

So the only solution is to test the output as XML. And to do that we'll need to parse it.

encoding/xml is the Go package that can handle all things to do with

simple XML parsing.

The function xml.Unmarshal takes

a []byte of XML data, and a pointer to a struct for it to get unmarshalled in

to.

So we'll need a struct to unmarshall our XML into. We could spend some time

working out what the correct names for all of the nodes and attributes, and how

to write the correct structure but, happily, someone has written

zek a program that will automate all of that

hard work for us. Even better, there's an online version at

https://www.onlinetool.io/xmltogo/. Just

paste the SVG from the top of the file into one box and - bam - out pops:

type Svg struct {

XMLName xml.Name `xml:"svg"`

Text string `xml:",chardata"`

Xmlns string `xml:"xmlns,attr"`

Width string `xml:"width,attr"`

Height string `xml:"height,attr"`

ViewBox string `xml:"viewBox,attr"`

Version string `xml:"version,attr"`

Circle struct {

Text string `xml:",chardata"`

Cx string `xml:"cx,attr"`

Cy string `xml:"cy,attr"`

R string `xml:"r,attr"`

Style string `xml:"style,attr"`

} `xml:"circle"`

Line []struct {

Text string `xml:",chardata"`

X1 string `xml:"x1,attr"`

Y1 string `xml:"y1,attr"`

X2 string `xml:"x2,attr"`

Y2 string `xml:"y2,attr"`

Style string `xml:"style,attr"`

} `xml:"line"`

}We could make adjustments to this if we needed to (like changing the name of the

struct to SVG) but it's definitely good enough to start us off. Paste the

struct into the clockface_test file and let's write a test with it:

func TestSVGWriterAtMidnight(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, time.UTC)

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, tm)

svg := Svg{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

x2 := "150"

y2 := "60"

for _, line := range svg.Line {

if line.X2 == x2 && line.Y2 == y2 {

return

}

}

t.Errorf("Expected to find the second hand with x2 of %+v and y2 of %+v, in the SVG output %v", x2, y2, b.String())

}We write the output of clockface.SVGWriter to a bytes.Buffer

and then Unmarshal it into an Svg. We then look at each Line in the Svg

to see if any of them have the expected X2 and Y2 values. If we get a match

we return early (passing the test); if not we fail with a (hopefully)

informative message.

./clockface_acceptance_test.go:41:2: undefined: clockface.SVGWriterLooks like we'd better write that SVGWriter...

package clockface

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"time"

)

const (

secondHandLength = 90

clockCentreX = 150

clockCentreY = 150

)

//SVGWriter writes an SVG representation of an analogue clock, showing the time t, to the writer w

func SVGWriter(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

io.WriteString(w, svgStart)

io.WriteString(w, bezel)

secondHand(w, t)

io.WriteString(w, svgEnd)

}

func secondHand(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

p := secondHandPoint(t)

p = Point{p.X * secondHandLength, p.Y * secondHandLength} // scale

p = Point{p.X, -p.Y} // flip

p = Point{p.X + clockCentreX, p.Y + clockCentreY} // translate

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%f" y2="%f" style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}

const svgStart = `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN" "https://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd">

<svg xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

width="100%"

height="100%"

viewBox="0 0 300 300"

version="2.0">`

const bezel = `<circle cx="150" cy="150" r="100" style="fill:#fff;stroke:#000;stroke-width:5px;"/>`

const svgEnd = `</svg>`The most beautiful SVG writer? No. But hopefully it'll do the job...

clockface_acceptance_test.go:56: Expected to find the second hand with x2 of 150 and y2 of 60, in the SVG output <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.1//EN" "https://www.w3.org/Graphics/SVG/1.1/DTD/svg11.dtd">

<svg xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

width="100%"

height="100%"

viewBox="0 0 300 300"

version="2.0"><circle cx="150" cy="150" r="100" style="fill:#fff;stroke:#000;stroke-width:5px;"/><line x1="150" y1="150" x2="150.000000" y2="60.000000" style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/></svg>

Oooops! The %f format directive is printing our coordinates to the default

level of precision - six decimal places. We should be explicit as to what level

of precision we're expecting for the coordinates. Let's say three decimal

places.

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%.3f" y2="%.3f" style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)And after we update our expectations in the test

x2 := "150.000"

y2 := "60.000"We get:

PASS

ok clockface 0.006s

We can now shorten our main function:

package main

import (

"os"

"time"

"github.com/gypsydave5/learn-go-with-tests/math/v7b/clockface"

)

func main() {

t := time.Now()

clockface.SVGWriter(os.Stdout, t)

}This is what things should look like now.

And we can write a test for another time following the same pattern, but not before...

Three things stick out:

- We're not really testing for all of the information we need to ensure is

present - what about the

x1values, for instance? - Also, those attributes for

x1etc. aren't reallystringsare they? They're numbers! - Do I really care about the

styleof the hand? Or, for that matter, the emptyTextnode that's been generated byzak?

We can do better. Let's make a few adjustments to the Svg struct, and the

tests, to sharpen everything up.

type SVG struct {

XMLName xml.Name `xml:"svg"`

Xmlns string `xml:"xmlns,attr"`

Width string `xml:"width,attr"`

Height string `xml:"height,attr"`

ViewBox string `xml:"viewBox,attr"`

Version string `xml:"version,attr"`

Circle Circle `xml:"circle"`

Line []Line `xml:"line"`

}

type Circle struct {

Cx float64 `xml:"cx,attr"`

Cy float64 `xml:"cy,attr"`

R float64 `xml:"r,attr"`

}

type Line struct {

X1 float64 `xml:"x1,attr"`

Y1 float64 `xml:"y1,attr"`

X2 float64 `xml:"x2,attr"`

Y2 float64 `xml:"y2,attr"`

}Here I've

- Made the important parts of the struct named types -- the

Lineand theCircle - Turned the numeric attributes into

float64s instead ofstrings. - Deleted unused attributes like

StyleandText - Renamed

SvgtoSVGbecause it's the right thing to do.

This will let us assert more precisely on the line we're looking for:

func TestSVGWriterAtMidnight(t *testing.T) {

tm := time.Date(1337, time.January, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, time.UTC)

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, tm)

svg := SVG{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

want := Line{150, 150, 150, 60}

for _, line := range svg.Line {

if line == want {

return

}

}

t.Errorf("Expected to find the second hand line %+v, in the SVG lines %+v", want, svg.Line)

}Finally we can take a leaf out of the unit tests' tables, and we can write

a helper function containsLine(line Line, lines []Line) bool to really make

these tests shine:

func TestSVGWriterSecondHand(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

line Line

}{

{

simpleTime(0, 0, 0),

Line{150, 150, 150, 60},

},

{

simpleTime(0, 0, 30),

Line{150, 150, 150, 240},

},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, c.time)

svg := SVG{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

if !containsLine(c.line, svg.Line) {

t.Errorf("Expected to find the second hand line %+v, in the SVG lines %+v", c.line, svg.Line)

}

})

}

}

func containsLine(l Line, ls []Line) bool {

for _, line := range ls {

if line == l {

return true

}

}

return false

}Here's what it looks like

Now that's what I call an acceptance test!

So that's the second hand done. Now let's get started on the minute hand.

func TestSVGWriterMinuteHand(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

line Line

}{

{

simpleTime(0, 0, 0),

Line{150, 150, 150, 70},

},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, c.time)

svg := SVG{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

if !containsLine(c.line, svg.Line) {

t.Errorf("Expected to find the minute hand line %+v, in the SVG lines %+v", c.line, svg.Line)

}

})

}

}clockface_acceptance_test.go:87: Expected to find the minute hand line {X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:70}, in the SVG lines [{X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:60}]

We'd better start building some other clock hands, Much in the same way as we produced the tests for the second hand, we can iterate to produce the following set of tests. Again we'll comment out our acceptance test while we get this working:

func TestMinutesInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(0, 30, 0), math.Pi},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := minutesInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}./clockface_test.go:59:11: undefined: minutesInRadians

func minutesInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return math.Pi

}Well, OK - now let's make ourselves do some real work. We could model the minute hand as only moving every full minute - so that it 'jumps' from 30 to 31 minutes past without moving in between. But that would look a bit rubbish. What we want it to do is move a tiny little bit every second.

func TestMinutesInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(0, 30, 0), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 7), 7 * (math.Pi / (30 * 60))},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := minutesInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}How much is that tiny little bit? Well...

- Sixty seconds in a minute

- thirty minutes in a half turn of the circle (

math.Piradians) - so

30 * 60seconds in a half turn. - So if the time is 7 seconds past the hour ...

- ... we're expecting to see the minute hand at

7 * (math.Pi / (30 * 60))radians past the 12.

clockface_test.go:62: Wanted 0.012217304763960306 radians, but got 3.141592653589793

In the immortal words of Jennifer Aniston: Here comes the science bit

func minutesInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return (secondsInRadians(t) / 60) +

(math.Pi / (30 / float64(t.Minute())))

}Rather than working out how far to push the minute hand around the clockface for

every second from scratch, here we can just leverage the secondsInRadians

function. For every second the minute hand will move 1/60th of the angle the

second hand moves.

secondsInRadians(t) / 60Then we just add on the movement for the minutes - similar to the movement of the second hand.

math.Pi / (30 / float64(t.Minute()))And...

PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

Nice and easy. This is what things look like now

Should I add more cases to the minutesInRadians test? At the moment there are

only two. How many cases do I need before I move on to the testing the

minuteHandPoint function?

One of my favourite TDD quotes, often attributed to Kent Beck,3 is

Write tests until fear is transformed into boredom.

And, frankly, I'm bored of testing that function. I'm confident I know how it works. So it's on to the next one.

func TestMinuteHandPoint(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(0, 30, 0), Point{0, -1}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := minuteHandPoint(c.time)

if !roughlyEqualPoint(got, c.point) {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}./clockface_test.go:79:11: undefined: minuteHandPoint

func minuteHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{}

}clockface_test.go:80: Wanted {0 -1} Point, but got {0 0}

func minuteHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return Point{0, -1}

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

And now for some actual work

func TestMinuteHandPoint(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(0, 30, 0), Point{0, -1}},

{simpleTime(0, 45, 0), Point{-1, 0}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := minuteHandPoint(c.time)

if !roughlyEqualPoint(got, c.point) {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}clockface_test.go:81: Wanted {-1 0} Point, but got {0 -1}

A quick copy and paste of the secondHandPoint function with some minor changes

ought to do it...

func minuteHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

angle := minutesInRadians(t)

x := math.Sin(angle)

y := math.Cos(angle)

return Point{x, y}

}PASS

ok clockface 0.009s

We've definitely got a bit of repetition in the minuteHandPoint and

secondHandPoint - I know because we just copied and pasted one to make the

other. Let's DRY it out with a function.

func angleToPoint(angle float64) Point {

x := math.Sin(angle)

y := math.Cos(angle)

return Point{x, y}

}and we can rewrite minuteHandPoint and secondHandPoint as one liners:

func minuteHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return angleToPoint(minutesInRadians(t))

}func secondHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return angleToPoint(secondsInRadians(t))

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

Now we can uncomment the acceptance test and get to work drawing the minute hand.

The minuteHand function is a copy-and-paste of secondHand with some

minor adjustments, such as declaring a minuteHandLength:

const minuteHandLength = 80

//...

func minuteHand(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

p := minuteHandPoint(t)

p = Point{p.X * minuteHandLength, p.Y * minuteHandLength}

p = Point{p.X, -p.Y}

p = Point{p.X + clockCentreX, p.Y + clockCentreY}

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%.3f" y2="%.3f" style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}And a call to it in our SVGWriter function:

func SVGWriter(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

io.WriteString(w, svgStart)

io.WriteString(w, bezel)

secondHand(w, t)

minuteHand(w, t)

io.WriteString(w, svgEnd)

}Now we should see that TestSVGWriterMinuteHand passes:

PASS

ok clockface 0.006s

But the proof of the pudding is in the eating - if we now compile and run our

clockface program, we should see something like

Let's remove the duplication from the secondHand and minuteHand functions,

putting all of that scale, flip and translate logic all in one place.

func secondHand(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

p := makeHand(secondHandPoint(t), secondHandLength)

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%.3f" y2="%.3f" style="fill:none;stroke:#f00;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}

func minuteHand(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

p := makeHand(minuteHandPoint(t), minuteHandLength)

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%.3f" y2="%.3f" style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}

func makeHand(p Point, length float64) Point {

p = Point{p.X * length, p.Y * length}

p = Point{p.X, -p.Y}

return Point{p.X + clockCentreX, p.Y + clockCentreY}

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

This is where we're up to now.

There... now it's just the hour hand to do!

func TestSVGWriterHourHand(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

line Line

}{

{

simpleTime(6, 0, 0),

Line{150, 150, 150, 200},

},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, c.time)

svg := SVG{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

if !containsLine(c.line, svg.Line) {

t.Errorf("Expected to find the hour hand line %+v, in the SVG lines %+v", c.line, svg.Line)

}

})

}

}clockface_acceptance_test.go:113: Expected to find the hour hand line {X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:200}, in the SVG lines [{X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:60} {X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:70}]

Again, let's comment this one out until we've got the some coverage with the lower level tests:

func TestHoursInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), math.Pi},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hoursInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}./clockface_test.go:97:11: undefined: hoursInRadians

func hoursInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return math.Pi

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

func TestHoursInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 0), 0},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hoursInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}clockface_test.go:100: Wanted 0 radians, but got 3.141592653589793

func hoursInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return (math.Pi / (6 / float64(t.Hour())))

}func TestHoursInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 0), 0},

{simpleTime(21, 0, 0), math.Pi * 1.5},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hoursInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}clockface_test.go:101: Wanted 4.71238898038469 radians, but got 10.995574287564276

func hoursInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return (math.Pi / (6 / (float64(t.Hour() % 12))))

}Remember, this is not a 24-hour clock; we have to use the remainder operator to get the remainder of the current hour divided by 12.

PASS

ok github.com/gypsydave5/learn-go-with-tests/math/v10/clockface 0.008s

Now let's try to move the hour hand around the clockface based on the minutes and the seconds that have passed.

func TestHoursInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 0), 0},

{simpleTime(21, 0, 0), math.Pi * 1.5},

{simpleTime(0, 1, 30), math.Pi / ((6 * 60 * 60) / 90)},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hoursInRadians(c.time)

if got != c.angle {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}clockface_test.go:102: Wanted 0.013089969389957472 radians, but got 0

Again, a bit of thinking is now required. We need to move the hour hand along

a little bit for both the minutes and the seconds. Luckily we have an angle

already to hand for the minutes and the seconds - the one returned by

minutesInRadians. We can reuse it!

So the only question is by what factor to reduce the size of that angle. One

full turn is one hour for the minute hand, but for the hour hand it's twelve

hours. So we just divide the angle returned by minutesInRadians by twelve:

func hoursInRadians(t time.Time) float64 {

return (minutesInRadians(t) / 12) +

(math.Pi / (6 / float64(t.Hour()%12)))

}and behold:

clockface_test.go:104: Wanted 0.013089969389957472 radians, but got 0.01308996938995747

Floating point arithmetic strikes again.

Let's update our test to use roughlyEqualFloat64 for the comparison of the

angles.

func TestHoursInRadians(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

angle float64

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), math.Pi},

{simpleTime(0, 0, 0), 0},

{simpleTime(21, 0, 0), math.Pi * 1.5},

{simpleTime(0, 1, 30), math.Pi / ((6 * 60 * 60) / 90)},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hoursInRadians(c.time)

if !roughlyEqualFloat64(got, c.angle) {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v radians, but got %v", c.angle, got)

}

})

}

}PASS

ok clockface 0.007s

If we're going to use roughlyEqualFloat64 in one of our radians tests, we

should probably use it for all of them. That's a nice and simple refactor,

which will leave things looking like this.

Right, it's time to calculate where the hour hand point is going to go by working out the unit vector.

func TestHourHandPoint(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

point Point

}{

{simpleTime(6, 0, 0), Point{0, -1}},

{simpleTime(21, 0, 0), Point{-1, 0}},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

got := hourHandPoint(c.time)

if !roughlyEqualPoint(got, c.point) {

t.Fatalf("Wanted %v Point, but got %v", c.point, got)

}

})

}

}Wait, am I going to write two test cases at once? Isn't this bad TDD?

Test driven development is not a religion. Some people might act like it is - usually people who don't do TDD but are happy to moan on Twitter or Dev.to that it's only done by zealots and that they're 'being pragmatic' when they don't write tests. But it's not a religion. It's a tool.

I know what the two tests are going to be - I've tested two other clock hands in exactly the same way - and I already know what my implementation is going to be - I wrote a function for the general case of changing an angle into a point in the minute hand iteration.

I'm not going to plough through TDD ceremony for the sake of it. TDD is a technique that helps me understand the code I'm writing - and the code that I'm going to write - better. TDD gives me feedback, knowledge and insight. But if I've already got that knowledge, then I'm not going to plough through the ceremony for no reason. Neither tests nor TDD are an end in themselves.

My confidence has increased, so I feel I can make larger strides forward. I'm going to 'skip' a few steps, because I know where I am, I know where I'm going and I've been down this road before.

But also note: I'm not skipping writing the tests entirely - I'm still writing them first. They're just appearing in less granular chunks.

./clockface_test.go:119:11: undefined: hourHandPoint

func hourHandPoint(t time.Time) Point {

return angleToPoint(hoursInRadians(t))

}As I said, I know where I am, and I know where I'm going. Why pretend otherwise? The tests will soon tell me if I'm wrong.

PASS

ok github.com/gypsydave5/learn-go-with-tests/math/v11/clockface 0.009s

And finally we get to draw in the hour hand. We can bring in that acceptance test by uncommenting it:

func TestSVGWriterHourHand(t *testing.T) {

cases := []struct {

time time.Time

line Line

}{

{

simpleTime(6, 0, 0),

Line{150, 150, 150, 200},

},

}

for _, c := range cases {

t.Run(testName(c.time), func(t *testing.T) {

b := bytes.Buffer{}

clockface.SVGWriter(&b, c.time)

svg := SVG{}

xml.Unmarshal(b.Bytes(), &svg)

if !containsLine(c.line, svg.Line) {

t.Errorf("Expected to find the hour hand line %+v, in the SVG lines %+v", c.line, svg.Line)

}

})

}

}clockface_acceptance_test.go:113: Expected to find the hour hand line {X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:200},

in the SVG lines [{X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:60} {X1:150 Y1:150 X2:150 Y2:70}]

And we can now make our final adjustments to the SVG writing constants and functions:

const (

secondHandLength = 90

minuteHandLength = 80

hourHandLength = 50

clockCentreX = 150

clockCentreY = 150

)

//SVGWriter writes an SVG representation of an analogue clock, showing the time t, to the writer w

func SVGWriter(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

io.WriteString(w, svgStart)

io.WriteString(w, bezel)

secondHand(w, t)

minuteHand(w, t)

hourHand(w, t)

io.WriteString(w, svgEnd)

}

// ...

func hourHand(w io.Writer, t time.Time) {

p := makeHand(hourHandPoint(t), hourHandLength)

fmt.Fprintf(w, `<line x1="150" y1="150" x2="%.3f" y2="%.3f" style="fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:3px;"/>`, p.X, p.Y)

}And so...

ok clockface 0.007s

Let's just check by compiling and running our clockface program.

Looking at clockface.go, there are a few 'magic numbers' floating about. They

are all based around how many hours/minutes/seconds there are in a half-turn

around a clockface. Let's refactor so that we make explicit their meaning.

const (

secondsInHalfClock = 30

secondsInClock = 2 * secondsInHalfClock

minutesInHalfClock = 30

minutesInClock = 2 * minutesInHalfClock

hoursInHalfClock = 6

hoursInClock = 2 * hoursInHalfClock

)Why do this? Well, it makes explicit what each number means in the equation. If - when - we come back to this code, these names will help us to understand what's going on.

Moreover, should we ever want to make some really, really WEIRD clocks - ones with 4 hours for the hour hand, and 20 seconds for the second hand say - these constants could easily become parameters. We're helping to leave that door open (even if we never go through it).

Do we need to do anything else?

First, let's pat ourselves on the back - we've written a program that makes an SVG clockface. It works and it's great. It will only ever make one sort of clockface - but that's fine! Maybe you only want one sort of clockface. There's nothing wrong with a program that solves a specific problem and nothing else.

But the code we've written does solve a more general set of problems to do with drawing a clockface. Because we used tests to think about each small part of the problem in isolation, and because we codified that isolation with functions, we've built a very reasonable little API for clockface calculations.

We can work on this project and turn it into something more general - a library for calculating clockface angles and/or vectors.

In fact, providing the library along with the program is a really good idea. It costs us nothing, while increasing the utility of our program and helping to document how it works.

APIs should come with programs, and vice versa. An API that you must write C code to use, which cannot be invoked easily from the command line, is harder to learn and use. And contrariwise, it's a royal pain to have interfaces whose only open, documented form is a program, so you cannot invoke them easily from a C program. -- Henry Spencer, in The Art of Unix Programming

In my final take on this program, I've made the

unexported functions within clockface into a public API for the library, with

functions to calculate the angle and unit vector for each of the clock hands.

I've also split the SVG generation part into its own package, svg, which is

then used by the clockface program directly. Naturally I've documented each of

the functions and packages.

Talking about SVGs...

I'm sure you've noticed that the most sophisticated piece of code for handling SVGs isn't in our application code at all; it's in the test code. Should this make us feel uncomfortable? Shouldn't we do something like

- use a template from

text/template? - use an XML library (much as we're doing in our test)?

- use an SVG library?

We could refactor our code to do any of these things, and we can do so because it doesn't matter how we produce our SVG, what is important is what we produce - an SVG. As such, the part of our system that needs to know the most about SVGs - that needs to be the strictest about what constitutes an SVG - is the test for the SVG output: it needs to have enough context and knowledge about what an SVG is for us to be confident that we're outputting an SVG. The what of an SVG lives in our tests; the how in the code.

We may have felt odd that we were pouring a lot of time and effort into those SVG tests - importing an XML library, parsing XML, refactoring the structs - but that test code is a valuable part of our codebase - possibly more valuable than the current production code. It will help guarantee that the output is always a valid SVG, no matter what we choose to use to produce it.

Tests are not second class citizens - they are not 'throwaway' code. Good tests will last a lot longer than the version of the code they are testing. You should never feel like you're spending 'too much time' writing your tests. It is an investment.

Footnotes

-

In short it makes it easier to do calculus with circles as π just keeps coming up as an angle if you use normal degrees, so if you count your angles in πs it makes all the equations simpler. ↩

-

This is a lot easier than writing a name out by hand as a string and then having to keep it in sync with the actual time. Believe me you don't want to do that... ↩

-

Misattributed because, like all great authors, Kent Beck is more quoted than read. Beck himself attributes it to Phlip. ↩