Package dependencyparser is a package that provides data structures and algorithms for a dependency parser as described by Chen and Manning 2014 [PDF]. It achieves similar accuracy scores as the the cited paper.

go get -u github.com/chewxy/lingo/dep

The core of the parser is a transition based parser, as popularized by Nivre 2003 [PDF]. It's essentially a shift-reduce parser with more states. Dan Jurafsky has a very complete overview of transition-based parsing [PDF], which should be consulted should more questions arise.

At the core of a transition based parser are two data structures: a stack and a queue. The queue, or buffer holds a list of words waiting to be parsed. Parsing is then simply a matter of manipulating the state of the stack and queue. Specifically there are three possible actions in an arc-standard parser:

Shift: Shift simply shifts one word from the buffer on to the top of the stackLeft: Left means the top of the stack is the head of the word underneath it. After the transition is applied (the link between the nodes attached), the word underneath the stack is removed.Right: Right means that the top of the stack is the child of the word underneath it. After the transition is applied, the top of the stack is popped.

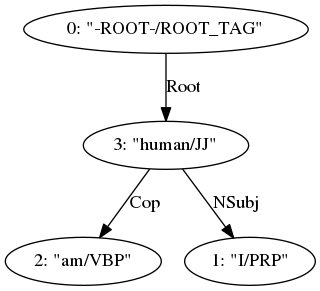

A word on the terms "head", and "child". Consider the sentence "I am human":

We say "human" is the head of the words "I" and "am". Therefore, "I" and "am" are considered to be children of "human".

Let's look at a simple example to concrefy the ideas: "The cat sat on the mat". Here are the states

| Step | Stack | Buffer | Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | [ROOT] | ["The", "cat", "sat", "on", "the", "mat"] | Shift |

| 1 | [ROOT, "The"] | ["cat", "sat", "on", "the", "mat"] | Shift |

| 2 | [ROOT, "The", "cat"] | ["sat", "on", "the", "mat"] | Left |

| 3 | [ROOT, "cat"] | ["sat", "on", "the", "mat"] | Shift |

| 4 | [ROOT, "cat", "sat"] | ["on", "the", "mat"] | Left |

| 5 | [ROOT, "sat"] | ["on", "the", "mat"] | Shift |

| 6 | [ROOT, "sat", "on"] | ["the", "mat"] | Shift |

| 7 | [ROOT, "sat", "on", "the"] | ["mat"] | Shift |

| 8 | [ROOT, "sat", "on", "the", "mat"] | [] | Left |

| 9 | [ROOT, "sat", "on", "mat"] | [] | Left |

| 10 | [ROOT, "sat", "mat"] | [] | Right |

| 11 | [ROOT, "sat"] | [] | Left |

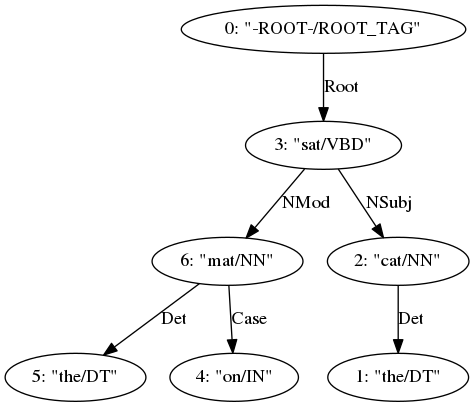

The above transitions produces this parse tree:

The real question then is of course - how does the system know which is the correct transition to emit, given the state?

The answer is machine learning.

What exactly are we learning? Or more carefully put, what are the inputs and outputs of the machine learning algorithm? The table in the example above provides a template for the inputs and output. The output is easy - the transition is what we want to learn.

As for the input, it's a little bit more complex. The input consists of the stack and the buffer. It'd be impractical and slow to include everything in the stack and buffer (dynamic neural networks are somewhat slower than static ones). So Chen and Manning came up with an ingenious idea -

- Use the top 3 words of the stack

- Use the top 3 words of the buffer

- Use the first and second leftmost/rightmost children of the first two words of the stack

Instead of directly using the words, POS Tag and dependency relations as features, the rather ingenious idea was that it would use vectors drawn from an embedding matrix to represent these features instead. So instead of building sparse features, concatenating the vectors form a fixed sized input vector. This makes training the network much more expedient. You'll find this in features.go

Given each state above, it'd be fairly trivial to extract an input vector based on the 18 "features" listed and feed forwards to a neural network. The result is a fast parser.

The machine learning algorithm behind this parser is a simple 3-layered network. An input layer is constructed from the embedding matrices, and is forwarded to the first layer, which is activated by a cube activation function. This then passes forwards to a dropout layer before the last layer, which is a softmax layer.

[image of NN]

The hairy bits of this is the oracle. Specifically, the question: given a training sentence, how do we generate correct examples such as the table above?

TODO: finish writing this section

This package provides three main data structures for use:

ParserModelTrainer

Trainer takes a []treebank.SentenceTag and produces a Model. Parser requires a Model to run, and is basically a exported wrapper over configuration that handles a pipeline.

func main() {

inputString: `The cat sat on the mat`

lx := lexer.New("dummy", strings.NewReader(inputString)) // lexer - required to break a sentence up into words.

pt := pos.New(pos.WithModel(posModel)) // POS Tagger - required to tag the words with a part of speech tag.

dp := dep.New(depModel) // Creates a new parser

// set up a pipeline

pt.Input = lx.Output

dp.Input = pt.Output

// run all

go lx.Run()

go pt.Run()

go dp.Run()

// wait to receive:

for {

select {

case d := <- dp.Output:

// do something

case err:= <-dp.Error:

// handle error

}

}

}To train a model you'd use the Trainer. The trainer accepts a []treebank.SentenceTag. As long as you can parse your training file into those (package treebank accepts CONLLU formatted files as well as the PennTreebank formatted files), you'd be fine.

An example trainer is in the cmd directory of lingo

Why not an LSTM or RNN to encode the state of the stack and buffer?

The answer is simplicity and speed. I have attempted variants of the parser with different neural networks - they don't work as fast as this. I am aware of Parsey-McParseface and the slightly improved accuracy compared to this model, but the speed has been not as great as I expect. This package emphasises parsing speed over accuracy - for most well written English sentences, this package performs well.

Why are there no models?

I'm afraid you're gonna have to train your own models. Training takes days on the Universal Dependency dataset and I haven't had the time to train on those. All my models are specific to the use of the company, and hence cannot be released.

What caveats are there?

Chen and Manning described using pre-computed activations for the top 10000 or so words. I did not implement that, but it would be trivial to revisit and implement it. Feel free to send a pull request.

How can this be sped up?

Use multiple, smaller trainers, each training on a separate batch. You can hence train them concurrently (pass the costs in a channel and collect at the end). At the end, sum the gradients before applying adagrad. The trade off is that a LOT more memory will be used. It's also the reason why it wasn't included as the default. It's quite trivial to write though. Send a pull request if you have managed to reduce memory usage.

see package lingo's CONTRIBUTING.md for more information. There is currently a list of issues in Github issues. Those are good places to start.

This package is MIT licenced.