Reasons why transforming bytes into a structured value with arbitrary does not work well for fuzzing purposes

I have not posted any benchmarks of fuzzcheck’s performance, and yet I claimed

that it can be much more efficient than libFuzzer paired with arbitrary.

There are a few reasons for the lack of benchmarks: fuzzcheck is still young

and changing fast and the mutators of many types are still not written. But

most of all, benchmarking is hard, and is especially so for fuzzers, whose

performance very much depend on the type of task at hand. A fuzzer can be

very fast on one test but become completely stuck on another test, while

another can be slow but more versatile. So before I post benchmarks, I want to

make sure that I have a range of meaningfully different structure-aware fuzz

targets. Such fuzz targets are difficult to find because fuzzing is still

mostly reserved for programs that deal with “unstructured” data. It has also

traditionally been something that security researchers do, and not regular

developers. My aim is to change that.

Based on my understanding of coverage-guided fuzzing, there are a couple of reasons to be optimistic, at least, about the fuzzcheck approach to structure-aware fuzzing. Some of them relate to performance (#iter/s) and efficiency (#iter to find crash), but some are also about ease-of-use and versatility.

While it may seem easy to write an implementation of Arbitrary, writing it

in a way that is easy for a fuzzer to meaningfully mutate the value is

difficult. And writing it in a way such it is composable is even more

difficult.

For example, consider how one can decode bytes into a value of type Option<u16>.

The obvious approach is as follows:

fn arbitrary(mut bytes: &mut Bytes) -> Option<u16> {

// consumes 1 byte

if let is_some = bytes.take_byte().is_odd() {

// consumes two bytes

let data = u16::arbitrary(&mut bytes);

Some(arbitrary(bytes))

} else {

None

}

}And it seems to work well, we obtain this mapping:

// A1 is odd, so it is true and a `Some` is created

"A1 67 F8 .." => Some(0x67F8)

// 00 is even, so it is false and a `None` is created

"00 .." => NoneSimilarly, we can easily write a function to parse a tuple of three elements:

fn arbitrary<T: Arbitrary>(bytes: &mut Bytes) -> (T, T, T) {

let first = T::arbitrary(&mut bytes);

let second = T::arbitrary(&mut bytes);

let third = T::arbitrary(&mut bytes);

(first, second, third)

}This also seems to work well. For (u8, u8, u8), we have:

"8A 78 BB" => ( 0x8A, 0x78, 0xBB )

"00 01 C0" => ( 0x00, 0x01, 0xC0 )However, composing these two arbitrary implementations result in a mapping

that is very fuzzer unfriendly. Consider the differences between two very

similar bitstrings, and the structured values they generate:

"00 93 EF 23 C0 86 01" => (None , Some(0xEF), Some(0xC0), None)

"01 93 EF 23 C0 86 01" => (Some(0x93), Some(0x23), None , None)By simply flipping one bit at the beginning of the bitstring, the entirety of the structured value was changed. The fuzzing engine thought that it was applying a small mutation to the input, but it ended up creating a whole new one! If this kind of behaviour happens too often, it breaks the mechanism by which coverage-guided fuzzing engines work, and their efficiency drops.

You can verify that it is indeed a problem by fuzzing a value of the type:

#[derive(Clone, arbitrary::Arbitrary, Debug, PartialEq)]

pub enum SomeEnum {

A(u8),

B(u16),

C(u8, u16),

D(u16, u16),

E,

}

use SomeEnum::*;and the test function below with

cargo-fuzz run fuzz_target_1 -s none -- -use_value_profile=1:

// these kinds of fuzz_targets are usually trivial for libFuzzer to solve

fuzz_target!(|data: Vec<SomeEnum>| {

if data.len() > 6

&& data[0] == E

&& data[1] == A(30)

&& data[2] == E

&& data[3] == A(8)

&& data[4] == E

&& data[5] == A(230)

&& data[6] == A(23)

{

panic!()

}

});We can see that it doesn't perform too bad. When I tried it, libFuzzer consistently found the crash after about 1 million iterations. However, try inversing the order of the conditions as follows:

fuzz_target!(|data: Vec<SomeEnum>| {

if data.len() > 6

&& data[6] == A(23)

&& data[5] == A(230)

&& data[4] == E

&& data[3] == A(8)

&& data[2] == E

&& data[1] == A(30)

&& data[0] == E

{

panic!()

}

});and you will find that libFuzzer takes a much longer time to find the crash, after about 3 to 6 million iterations. The difference does not appear too bad because libFuzzer can apply multiple bitstring mutations in a row and merge (“crossover”) different inputs together, which makes up for the fuzzer-hostile encoding. If we disable these mutation techniques, it is easier to see the difference between those two tests. We can do that by running:

cargo fuzz run fuzz_target_1 fuzz -s none -- -use_value_profile=1 -mutate_depth=1 -cross_over=0

On the first test, we can still find the crash in about 1 million iterations. But on the second test, I stopped the fuzzing engine after 40 million iterations because I did not want to keep waiting. It may have eventually found the crash, or it may have stayed stuck forever.

The problem is that when libFuzzer finds an input that satisfies

data[6] == A(23), the whole of the input may look like:

data1 = [C(0, 1), B(8978), A(8), E, B(780), C(2, 900), A(23)]

And then changing the variant of any element in data1 will change its last

element too. Therefore the new mutated data1 will fail to get past the first

condition. The fuzzer is at a dead end.

There is, as far as I know, no easy way to deal with this problem, and it gets

worse as the type of the value we want to generate gets more complex. Other

types that suffer from this problem are: (Vec<..>, Vec<..>), Vec<Vec<..>>

and similar nested collections or enums.

In fuzzcheck, there is no performance difference between the two tests above (they both finish within 40,000 iterations) because mutators compose much better. Changing a value inside a vector does not affect the rest of the vector.

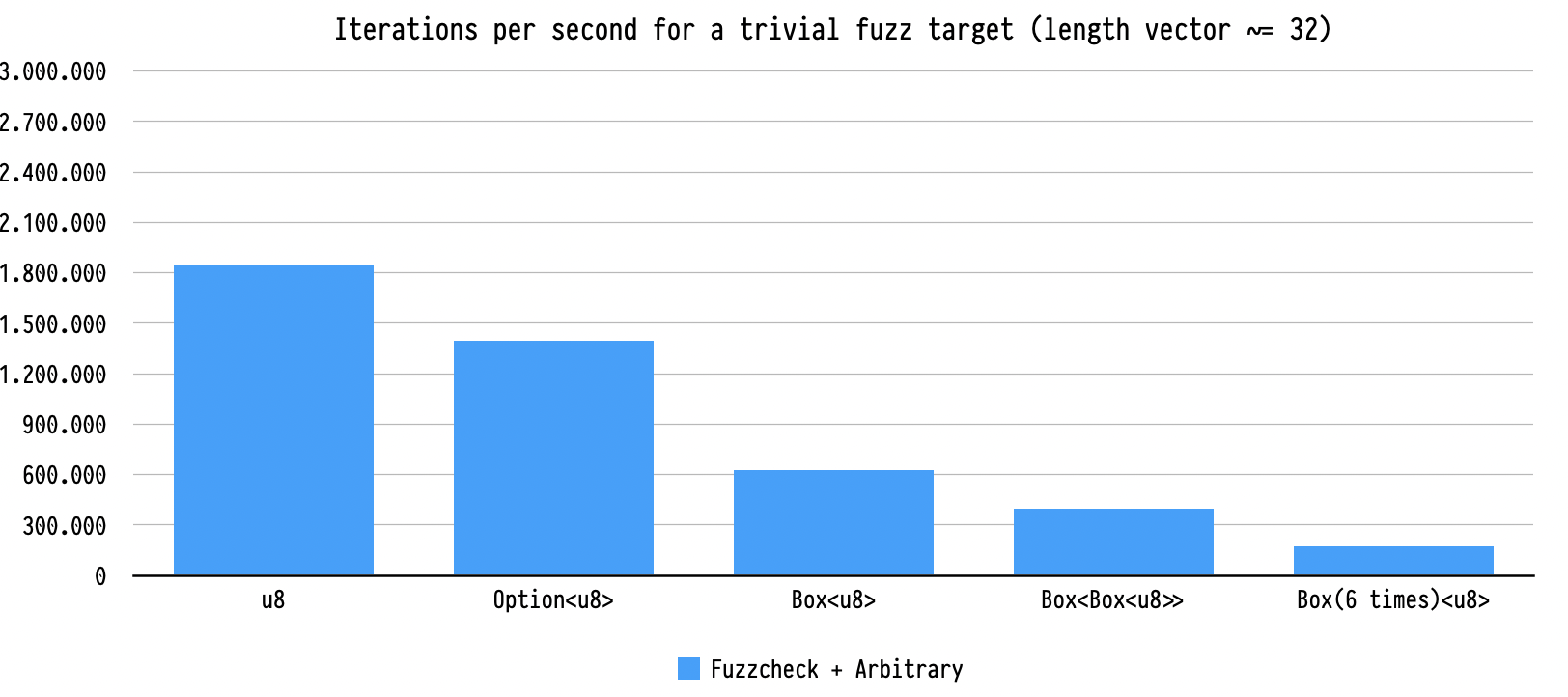

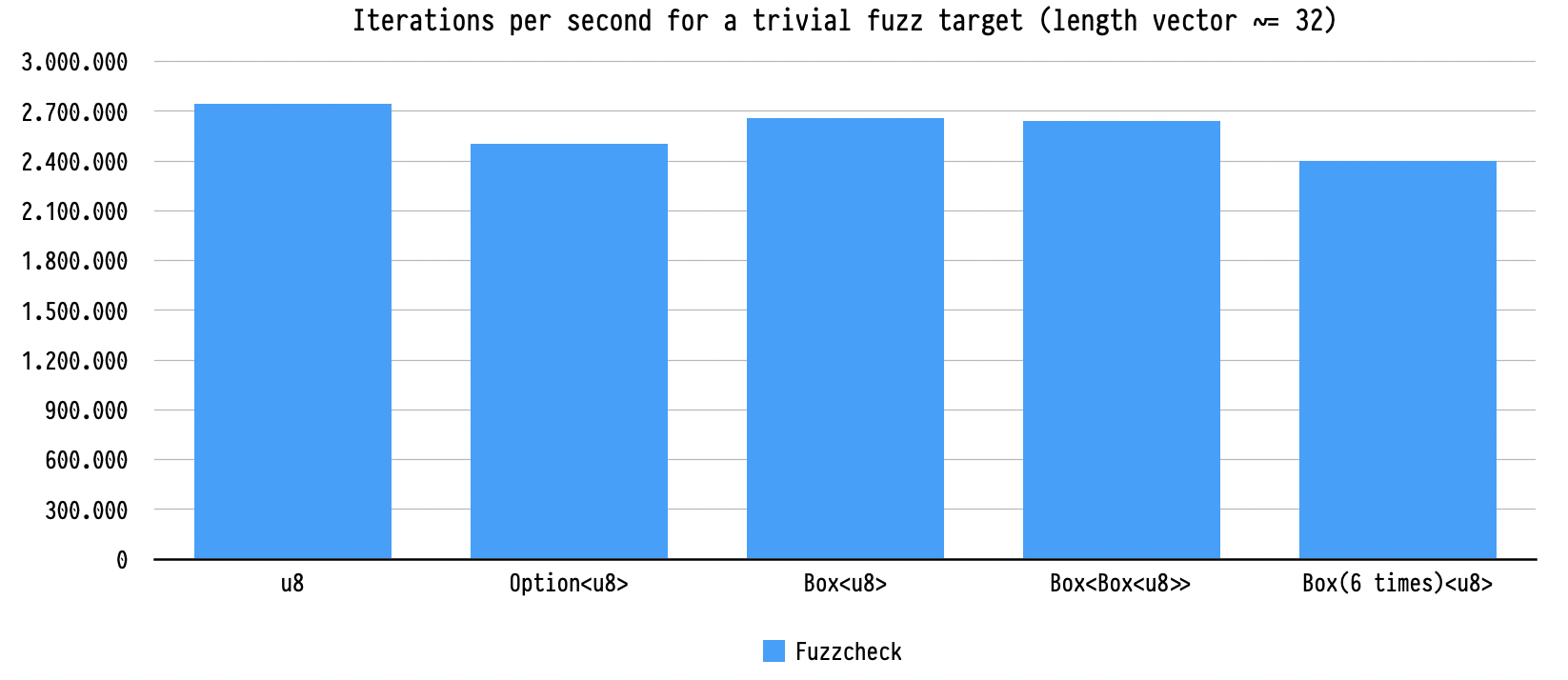

In most cases, I expect the fuzzer to spend most of its time within the test

function or analyzing code coverage. However, it is still important to

generate values quickly. By using arbitrary to parse a bitstring,

a lot of time is wasted creating a whole new value at each iteration, which can

sometimes be significant. To illustrate this, I measured the number of

iterations per second performed by fuzzcheck on a trivial fuzz target (similar

to the one in the example above). For the first benchmark, its own internal

mutator is used. For the second benchmark, it generates values of type

Vec<u8> and gives them to arbitrary to generate a vector of a

structured value. The results of that experiment are shown below:

Repeated allocations can significantly decrease the speed of the fuzzer.

Generating a vector of 32 bytes through arbitrary allows 1,800,000 iterations

per second. But if those bytes are boxed, the iteration speed drops to 625,000

iter/s. And for the run when the bytes were wrapped in a box six times, it

dropped to 170,000 iter/s. Because fuzzcheck’s mutator is able to mutate the

generated inputs in place, it doesn't suffer from this problem. In all cases,

the iteration speed stayed above 2,400,000 iter/s.

Whether that is a problem will depend on your use case. I expect that for many

tasks, the input generation time will not matter much. However, it is good to

know that fuzzcheck’s mutator can, at least in theory, handle much more complex

inputs than arbitrary. Imagine you are writing property tests for a graph

data structure. With arbitrary, the fuzzer will need to reconstruct the

whole graph every time, even if the only thing that changed is an integer

inside one of its nodes. With fuzzcheck, the node can be modified in-place.

TODO: the corpora produced by libFuzzer + arbitrary are unreadable by

humans. It is difficult to manually add inputs to a corpus. Similarly, it is

impossible to define “dictionaries” of important values (or sub-values)

to test.

TODO: libFuzzer performs many clever mutations that treat part of the bitstring as a String, or as an integer. But it doesn't actually know whether these parts are indeed strings or integers. In most cases, they won't be, and the mutation will be meaningless. In fuzzcheck, all mutations are specific to the type of the input or sub-input. In general, very few of the mutations that libFuzzer will perform are actually meaningful. For example, swapping two bytes in the bitstring is useless if one byte is used for control flow and the other is used to generate an integer.

TODO: a type can only implement Arbitrary once, whereas multiple fuzzcheck

mutators can be written for the same type. For example, it would be possible

to write a mutator that produces only Strings conforming to a certain regular

expression. It also makes mutators composable such that one can add

“strategies” on top of existing mutators (TODO: explore some strategies in more

details).

TODO: how do you generate a value of type Option<u8>? First you need to

choose whether it is None or Some. But how often should None be chosen?

If one chooses None half of the time, then a lot of the same values will be

produced over and over again. If one reduces its frequency to, say, 1 out of

100 times, then it deprioritizes a value that is very important to test! For

example, for the type (Option<T>, Option<T>, Option<T>), the value

(None, None, None) would only be generated one time over a million given a

random bitstring. Fuzzcheck’s mutations can be ordered. The first time that

an Option<T> is generated, one will get a None, and then never again after

that.