Wapping

| Wapping | |

|---|---|

The Town of Ramsgate pub, between Wapping High Street and the Thames. | |

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 12,411 (2011 Census.St. Katharine's and Wapping Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ345805 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | E1W |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Wapping (/ˈwɒpɪŋ/) is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between St Katharine Docks to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This position gives the district a strong maritime character.

The area was historically composed of two parishes, St George in the East, and the much smaller St John's. Urbanisation of the shoreline began in earnest after the draining of Wapping marsh, and the consolidation of the river wall in the late 16th century. Many of the original buildings were demolished during the construction of the London Docks and Wapping was further seriously damaged during the Blitz. As the London Docklands declined after the Second World War, the area became run down, with the great warehouses left empty. Some were demolished, but others such as Tobacco Dock survive. The area underwent further change during the 1980s when warehouses started to be converted into luxury flats.

Rupert Murdoch moved his News International printing and publishing works into Wapping in 1986, resulting in a trade union dispute that became known as the "Battle of Wapping".

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Formerly, it was believed that the name Wapping recorded an Anglo-Saxon settlement linked to a personal name Waeppa ("the settlement of Waeppa's people").[2] More recent scholarship discounts that theory: much of the area was marshland, where early settlement was unlikely, and no such personal name has ever been found. It is now thought that the name may derive from wapol, a marsh.[3]

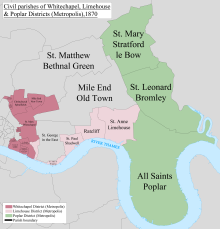

Wapping was historically part of the Manor and Parish of Stepney. By the 17th century, it formed two autonomous Hamlets, a Hamlet in this context refers to an autonomous area of a parish rather than a small village. The northern Hamlet was known as Wapping-Stepney, as it was the part of Wapping within Stepney, the riverside part was known as Wapping-Whitechapel as it was the part within the parish of Whitechapel, a parish which was previously also a part of the parish of Stepney.

These Hamlets later became independent parishes, with Wapping-Stepney becoming known as St-George-in-the-East (in 1729) and Wapping-Whitechapel known as St John of Wapping (in 1694). The latter occupied a very narrow strip along nearly all of Wapping's riverside.[4]

The Wapping parishes were part of the historic (or ancient) county of Middlesex, but military and most (or all) civil county functions were managed more locally, by the Tower Division (also known as the Tower Hamlets).

The role of the Tower Division ended when Wapping became part of the new County of London in 1889. The County of London was replaced by Greater London in 1965.

Riverside development

[edit]The draining of Wapping Marsh, and the consolidation of a river wall along which houses were built, were finally achieved by 1600 after previous attempts had failed. (See Embanking of the tidal Thames). The settlement developed along that river wall, hemmed in by the river to the south and the now-drained Wapping Marsh to the north This gave it a peculiarly narrow and constricted shape, consisting of little more than the axis of Wapping High Street and some north–south side streets. John Stow, the 16th-century historian, described it as a "continual street, or a filthy strait passage, with alleys of small tenements or cottages, built, inhabited by sailors' victuallers".[5] A chapel to St. John the Baptist was built in 1617, and it was here that Thomas Rainsborough was buried. Wapping was constituted as a parish in 1694.[6]

Wapping's proximity to the river gave it a strong maritime character for centuries, well into the 20th century. It was inhabited by sailors, mastmakers, boatbuilders, blockmakers, instrument-makers, victuallers and representatives of all the other trades that supported the seafarer. Wapping was also the site of 'Execution Dock', where pirates and other water-borne criminals faced execution by hanging from a gibbet constructed close to the low water mark. Their bodies would be left dangling until they had been submerged three times by the tide.[5]

The Bell Inn, by the execution dock, was run by Samuel Batts, whose daughter, Elizabeth, married James Cook at St Margaret's Church, Barking, Essex on 21 December 1762, after the Royal Navy captain had stayed at the Inn.[7] The couple initially settled in Shadwell, attending St Paul's church, but later moved to Mile End. Although they had six children together, much of their married life was spent apart, with Cook absent on his voyages and, after his murder in 1779 at Kealakekua Bay, she survived until 1835.

Said to be England's first, the Marine Police Force was formed in 1798 by magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and a Master Mariner, John Harriott, to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the Pool of London and the lower reaches of the river. Its base was (and remains) in Wapping High Street and it is now known as the Marine Support Unit.[8] The Thames Police Museum, dedicated to the history of the Marine Police Force, is currently housed within the headquarters of the Marine Support Unit, and is open to the public by appointment.[9]

In 1811, the Ratcliff Highway murders took place nearby at The Highway and Wapping Lane.[10]

London Docks

[edit]The area's strong maritime associations changed radically in the 19th century when the London Docks were built to the north and west of the High Street. Wapping's population plummeted by nearly 60% during that century, with many houses destroyed by the construction of the docks and giant warehouses along the riverfront. Squeezed between the high walls of the docks and warehouses, the riverside area became isolated from the rest of London, although some relief was provided by Brunel's Thames Tunnel to Rotherhithe. The opening of Wapping tube station on the East London line in 1869 provided a direct rail link to the rest of London.[11][12]

Migration

[edit]Wapping's position by the Thames has meant it has long attracted people from around the world. In the 15th century, the population of the area included a number of foreigners, in particular seamen from the Low Countries.[13]

There was a sizeable Irish presence in Wapping from the 16th century onward.[14] It is probably under their influence a stretch of Cable Street, and the area around it, become called Knock Fergus.[15] The Irish name of Knock Fergus (sometimes spelled Knock Vargis) is first known to be recorded in 1597[16] and continued to be recorded in Stepney parish rolls in the 1600's.[17] Knock Fergus (the hill of Fergus) is an old name for Carrickfergus in County Antrim. In the 20th century Irish migration to Wapping slowed and by the middle of the century the local Irish community had been assimilated.[18]

In 1702, a French-speaking church established at Milk Alley, next to St Johns Church, close to the shore in western Wapping. The church was established to support a community of French speaking seafarers originating in Jersey and Guernsey who had been joined by Huguenot refugees from France. There seems to have been a good relationship with the rest of the population as it received financial support from the Rector of St Johns, when it was in financial difficulty, and its long term future was settled by an intervention from Queen Anne who provided it with an allowance.[19]

Starting in the 16th century, and accelerating later, parts of Wapping attracted large number of German migrants, with many of these people, and their descendants working in the sugar industry. The area north of The Highway (formerly St George's Highway) and west of Cannon Street became known – together with neighbouring parts of Whitechapel – as Little Germany.[20]

There appears to have been a considerable black presence in late 18th century Wapping, on account of the many black and mulatto (mixed race) people, often seamen, being baptised at the two parish churches of St John's and in particular St George in the East.[21] There appears to also have been a sizeable black population in the areas to the west, the parish of St Botolph without Aldgate[22][23] (both the Portsoken and East Smithfield areas of the parish, and possibly also in St Katharine's Precinct, a densely populated little district that was swept away to build St Katharine Docks.

Modern times

[edit]

Wapping was devastated by German bombing in the Second World War[24] and by the post-war closure of the docks. It remained a run-down and derelict area into the 1980s, when the area was transferred to the management of the London Docklands Development Corporation, a government quango with the task of redeveloping the Docklands. The London Docks were largely filled in and redeveloped with a variety of commercial, light industrial and residential properties.

St John's Church, Wapping (1756) was located on what is now Scandrett Street. Only the tower and shell survived wartime bombing, and have now been converted to housing.[25]

Wapping dispute

[edit]The "Wapping dispute" or "Battle of Wapping" was, along with the miners' strike of 1984–85, a significant turning point in the history of the trade union movement and of UK industrial relations. It started on 24 January 1986 when some 6,000 newspaper workers went on strike after protracted negotiation with their employer, News International (parent of Times Newspapers and News Group Newspapers, and chaired by Rupert Murdoch). News International had built and clandestinely equipped a new printing plant for all its titles in Wapping, and when the print unions announced a strike it activated this new plant with the assistance of the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union (EETPU).

The plant was nicknamed "Fortress Wapping" when the sacked print workers effectively besieged it, mounting round-the-clock pickets and blockades in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to thwart the move. In 2005, News International announced the intention to move the print works to regional presses based in Broxbourne (the world's largest printing plant, opened March 2008),[26] Liverpool and Glasgow. The editorial staff were to remain, however, and there was talk of redeveloping the sizeable plot that makes up the printing works.[27]

Landmarks

[edit]

Perhaps Wapping's greatest attraction is the Thames foreshore itself and the venerable public houses that face onto it. A number of the 'watermen's stairs', such as Wapping Old Stairs and Pelican Stairs (by the Prospect of Whitby), give public access to a littoral zone (for the Thames is tidal at this point) littered with flotsam, jetsam and fragments of old dock installations. The area is popular with amateur archaeologists and treasure hunters. This activity is known as mudlarking; the term for a shore scavenger in the 18th and 19th centuries was a mudlark.

St George in the East, on Cannon Street Road, is one of six Hawksmoor churches in London, built from 1714 to 1729, with funding from the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches. The church was hit by a bomb during the Blitz and the original interior was destroyed by the fire, but the walls and distinctive pepper-pot towers remained intact. In 1964, a modern church interior was constructed inside the existing walls for the active congregation and a new flat built under each corner tower. Behind the church lies St George's Gardens, the original cemetery, which was passed to Stepney Council to maintain as a public park in mid-Victorian times. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the crypt of the church was used as a public air raid shelter and was fully occupied when the aforementioned bomb struck; there were no casualties and everyone was evacuated safely, thanks to the air raid wardens and fire brigade.

St John's Church, Wapping, the oldest church in Wapping, built in 1756 by Joel Johnson, was also hit by a bomb during WWII. The distinctive lead-topped tower remains and the former churchyard is a public park. Adjoining the church is St John's Old School, founded c.1695 for the new parish and rebuilt together with the church in 1756.

The Execution Dock was located on the Thames. It was used by the Admiralty for over 400 years (as late as 1830) to hang pirates that had been convicted and sentenced to death by the Admiralty court. The Admiralty only had jurisdiction over crimes on the sea, so the dock was located within their jurisdiction by being located far enough offshore as to be beyond the low-tide mark. It was used to kill the notorious Captain Kidd.[28] Many prisoners would be executed together as a public event in front of a crowd of onlookers after being paraded from the Marshalsea Prison across London Bridge and past the Tower of London to the dock.

Tobacco Dock is a Grade I listed warehouse, adjacent to The Highway. It was constructed in approximately 1811 and served primarily as a store for imported tobacco. In 1990, it was converted into a shopping centre at a development cost of £47 million with the intention to create the "Covent Garden of the East End"; the scheme was unsuccessful though and went into administration. Since the mid-1990s, the building has been almost entirely unoccupied; it is now occasionally used for filming, and for large corporate and commercial events.

Three venerable public houses are located near the Stairs. By Pelican Stairs is the Prospect of Whitby, formerly the Devil's Tavern,[29] which has a much-disputed claim to be the oldest Thames-side public house still in existence.[30] Be that as it may, there has been an inn on the site since the reign of Henry VIII and it is certainly one of the most famous public houses in London. It is named after a then-famous collier that used to dock regularly at Wapping. A replica of the old Execution Dock gibbet is maintained on the adjacent foreshore, although the actual site of Execution Dock was nearer to the Town of Ramsgate. This also is on the site of a 16th-century inn and is located next to Wapping Old Stairs to the west of the Prospect; by Wapping Pier Head – the former local headquarters of the Customs and Excise.

Situated halfway between the two is the Captain Kidd, named after the Scottish privateer William Kidd. He was hanged on the Wapping foreshore in 1701 after being found guilty of murder and piracy.[31] Although the pub occupies a 17th-century building, it was only established in the 1980s.

Education

[edit]Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]

The local station is Wapping on the London Overground's East London line; it is in Travelcard Zone 2.[32] There are regular direct services to Dalston Junction, Highbury & Islington, West Croydon, Crystal Palace, New Cross and Clapham Junction.[33]

The narrowness of the platforms means that the station does not fully meet the safety standards for an underground station, but is permitted to operate under a derogation from His Majesty's Railway Inspectorate.[34]

Formerly on the London Underground, the Metropolitan and the District Railways were the first lines to serve the station on 1 October 1884,[11] but the station was last served by District trains on 31 July 1905.[11][12] The East London line closed as an Underground route on 22 December 2007; it was rebranded and reopened on 27 April 2010 when it became part of the Overground system.

Buses

[edit]London bus services are operated by London Central and Stagecoach London. Routes include the 100, D3 and night bus N551; these connect Wapping with East and Central London.[35]

Roads

[edit]Wapping is connected to the National Road Network by The Highway A1203 east–west, which passes to the north of the area.

Cycling, walking and waterways

[edit]The Thames Path passes west–east through Wapping for cyclists and walkers.

Thames River Services operate a sightseeing boat route between Westminster and Greenwich, which call at Wapping. [36]

The Ornamental Canal runs through the area, mostly in the centre, to Shadwell Basin.

Notable people

[edit]People who were born in Wapping include:

- John Newton, Anglican clergyman and author of many hymns including Amazing Grace[37]

- Thomas Rainsborough (1610–1648), Parliamentarian soldier and Leveller.

- Walter Kennedy, a notorious early 18th century pirate

- Godscall Paleologue, last heir of the Eastern Roman Empire, born in Wapping and baptised at St Dunstan's, Stepney in 1694.[38]

- Arthur Orton, the Tichborne Claimant

- Les Reed, football coach and former manager of Charlton Athletic

People who lived in Wapping:

- Theodorious Paleologus, Barbados born privateer, and heir to the Eastern Roman Empire, lived in Wapping.[39]

- Daniel Day (1682-1767), marine engineer and founder of the Fairlop Fair, ran a business in Wapping.

- The American painter James McNeill Whistler, well known for his Thames views, painted Wapping (1860–1864) after returning to London from Paris in May 1859. Whistler took lodgings in Wapping where he explored the Thames to the east of the City of London.[40] The painting is permanently displayed at the National Gallery of Art Washington.

- During the 1990s, Wapping was home to American singer and actress Cher.[41]

- TV presenter Graham Norton.[42]

- Actress Helen Mirren lives in Wapping.[43]

In popular culture

[edit]

Wapping has been used as the setting for a number of works of fiction, including:

- The Long Good Friday;

- The Doctor Who episode "The Talons of Weng-Chiang";[44]

- The Ruby in the Smoke novel in the Sally Lockhart series by Phillip Pullman;[45]

- The BBC sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, in which the central character, Alf Garnett, shares his name with Garnet Street in Wapping;[46]

- Season 4, episode 23 of Friends, "The One with Ross's Wedding", which features St John's Church, Wapping

- The brothel in The Threepenny Opera, in which Mack the Knife is betrayed by Jenny Diver.

- The Darlings of Wapping Wharf Launderette is a compilation album by East End group the Small Faces.[47]

- The plot of Alfred Hitchcock's 1934 film The Man Who Knew Too Much included the gangsters' hideout, which was set in Wapping.[48]

- A house left standing after the London Blitz, the nearby River Thames and a notional priory house (which was used as a temporary prison) feature prominently in Jack Higgins' sequel to The Eagle Has Landed titled The Eagle Has Flown.

- The 1967 film To Sir, with Love was shot in Wapping, where the action in E. R. Braithwaite's 1959 autobiographical novel of the same name was set, based on his experience teaching at St George-in-the-East Central School (now the Mulberry House apartments),[49] adjacent to the north side of St George in the East church.[50]

- In the Monty Python skit "The Gumby Cherry Orchard," the narrator informs us that "Mr. L.N. Gumby is now appearing in the Thames near Wapping Steps."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Tower Hamlets Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ "Stepney: Settlement and Building to c.1700." in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, ed. T F T Baker (London: Victoria County History, 1998), 13–19. British History Online, accessed 1 May 2017, "Stepney: Settlement and Building to c.1700 | British History Online". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017..

- ^ 'Stepney: Early Stepney', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, ed. T F T Baker (London, 1998), pp. 1–7. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol11/pp1-7 [accessed 9 September 2022].

- ^ a b 'The Thames Tunnel, Ratcliff Highway and Wapping', Old and New London: Volume 2 (1878), pp. 128–37 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed: 29 March 2007

- ^ Maddocks, Sydney (December 1932). "Wapping". The Copartnership Herald. II (22). Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- ^ Famous 18th century people of Barking and Dagenham Info Sheet #22, LB Barking & Dagenham

- ^ History of the Marine Support Unit (Met) accessed 24 January 2007

- ^ Thames Police Museum Archived 22 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 June 2010

- ^ Stepney Murders: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders accessed 21 January 2007

- ^ a b c Rose 2007

- ^ a b Day 1979, p. 32

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby, p28 – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ My East End, A History of cockney London. Gilda o'Neill p54-55

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby, p54 – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ The Place Names of Middlesex – English Place name Society – Vol 18 – Gover Maw and Stenton – Cambridge University Press – p157 – 1942

- ^ Overview and map of the place name Knock Fergus https://www.theundergroundmap.com/article.html?id=65458

- ^ East London Papers, Volume 6, Number 2, The Irish in East London, December 1963, John A Jackson.

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby, p50 – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ East London Record – No 13 – 1990 https://www.mernick.org.uk/elhs/Record/ELHS%20RECORD%2013%20(1990).pdf

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby, p52-3 – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ citeweb https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18903391

- ^ citeweb: Source refers to the Shovel Public House in neighbouring East Smithfield (https://www.stgitehistory.org.uk/history.html

- ^ My Mum's War: Life in the East End – BBC WW2 People's War Archived 11 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine accessed 1 April 2007

- ^ "A Shadwell & Wapping Walk". Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "World's biggest print plant opens". BBC News. 17 March 2008.

- ^ Daily Telegraph Money 9 February 2006 Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed 5 May 2007

- ^ "Expired website – This website has expired". Archived from the original on 15 March 2009.

- ^ Lincoln, Margarete (2018). Trading in War: London's Maritime World in the Age of Cook and Nelson. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300235388., p.16

- ^ "Prospect of Whitby". Time Out London. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

- ^ "Execution of Captain Kidd". Archived from the original on 15 May 2018.

- ^ Baker 2007, p. 22, section B1

- ^ "London Overground Timetables". May 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "The Future of Wapping London Underground station" (PDF). Tower Hamlets London Borough Council. 28 January 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "Stops in Wapping, London". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "Thames River Sightseeing". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ John Newton Archived 17 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 7 February 2012

- ^ Hall, John (2015). An Elizabethan Assassin: Theodore Paleologus: Seducer, Spy and Killer. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750962612.

- ^ Hall, John (2015). An Elizabethan Assassin: Theodore Paleologus: Seducer, Spy and Killer. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750962612.

- ^ Fitzwilliam Museum Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 June 2015

- ^ "Homes with celebrity connections for sale". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Graham Norton: 'I had ambition at 40. That seems to have gone'". The Independent. 19 October 2012.

- ^ "My London: Helen Mirren". 12 April 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2022

- ^ "Wapping Old Stairs – The Locations Guide to Doctor Who, Torchwood and The Sarah Jane Adventures". The Locations Guide to Doctor Who, Torchwood, and the Sarah Jane Adventures. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009.

- ^ "Damaris.org". Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Wapping". Archived from the original on 12 September 2007.

- ^ Darlings of Wapping Wharf Launderette Retrieved 16 September 2008

- ^ "The Man Who Knew Too Much". British Film Institute/Sight and sound. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "St George-in-the-East Church | Board Schools | Cable Street". stgitehistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

After the Second World War it became a secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School… and has now been converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House'.

- ^ "To Sir, With Love | 1967". movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, S. K. (April 2007) [1977]. Rail Atlas Great Britain & Ireland (11th ed.). Hersham: Oxford Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-86093-602-2. 0704/K.

- Darby, Madge, Waeppa's People: History of Wapping, Connor & Butler (Dec 1988), ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- Day, John R. (1979) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (6th ed.). Westminster: London Transport. ISBN 0-85329-094-6. 1178/211RP/5M(A).

- Leigh, Martha, Memories of Wapping 1900–1960: Couldn't Afford the Eels, The History Press Ltd (4 July 2008), ISBN 0-7524-4709-2

- National Council for Civil Liberties, No Way in Wapping: Effect of the Policing of the News International Dispute on Wapping Residents, Civil Liberties Trust (May 1986), ISBN 0-946088-27-6

- Rose, Douglas (December 2007) [1980]. The London Underground: A Diagrammatic History (8th ed.). Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-315-0.