Zanzibar

Zanzibar | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Mungu ibariki Afrika (Swahili) "God Bless Africa"[1] | |

Location of Zanzibar within Tanzania | |

| |

| Status | Semi-autonomous region of Tanzania |

| Capital | Zanzibar City |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Zanzibari |

| Government | Federacy |

| Hussein Mwinyi | |

| Othman Masoud Sharif | |

| Hemed Suleiman Abdalla | |

| Legislature | House of Representatives |

| Establishment history | |

| 10 December 1963 | |

| 12 January 1964 | |

• Unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar | 26 April 1964 |

| Area | |

• Total[3] | 2,462 km2 (951 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 1,889,773 |

• Density | 768.2/km2 (1,989.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $3.75 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $2,500 |

| HDI (2020) | 0.720[5] high |

| Currency | Tanzanian shilling (TZS) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +255 |

| Internet TLD | .tz |

Zanzibar[a] is an insular semi-autonomous region which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, 25–50 km (16–31 mi) off the coast of the African mainland, and consists of many small islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. The capital is Zanzibar City, located on the island of Unguja. Its historic centre, Stone Town, is a World Heritage Site.

Zanzibar's main industries are spices, raffia, and tourism.[6] The main spices produced are clove, nutmeg, cinnamon, coconut, and black pepper. The Zanzibar Archipelago, together with Tanzania's Mafia Island, are sometimes referred to locally as the "Spice Islands". Tourism in Zanzibar is a more recent activity, driven by government promotion that caused an increase from 19,000 tourists in 1985,[7] to 376,000 in 2016.[8] The islands are accessible via 5 ports and the Abeid Amani Karume International Airport, which can serve up to 1.5 million passengers per year.[9]

Zanzibar's marine ecosystem is an important part of the economy for fishing and algaculture and contains important marine ecosystems that act as fish nurseries for Indian Ocean fish populations. Moreover, the land ecosystem is the home of the endemic Zanzibar red colobus, the Zanzibar servaline genet, and the extinct or rare Zanzibar leopard.[10][11] Pressure from the tourist industry and fishing as well as larger threats such as sea level rise caused by climate change are creating increasing environmental concerns throughout the region.[12]

Etymology

The word Zanzibar came from Arabic zanjibār (زنجبار [zandʒibaːr]), which is in turn from Persian zangbâr (زنگبار [zæŋbɒːɾ]), a compound of Zang (زنگ [zæŋ], "black") + bâr (بار [bɒːɾ], "coast"),[13][14][15] cf. the Sea of Zanj. The name is one of several toponyms sharing similar etymologies, ultimately meaning "land of the blacks" or similar meanings, in reference to the dark skin of the inhabitants.

History

Before 1498

The presence of microliths suggests that Zanzibar has been home to humans for at least 20,000 years,[16] which was the beginning of the Later Stone Age.

A Greco-Roman text between the 1st and 3rd centuries, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, mentioned the island of Menuthias (Ancient Greek: Μενουθιάς), which is probably Unguja.[17]

At the outset of the first millennium, both Zanzibar and the nearby coast were settled by Bantu speakers. Archaeological finds at Fukuchani, on the northwest coast of Zanzibar, indicate a settled agricultural and fishing community from the 6th century at the latest. The considerable amount of daub found indicates timber buildings, and shell beads, bead grinders, and iron slag have been found at the site. There is evidence of limited engagement in long-distance trade: a small amount of imported pottery has been found, less than 1% of total pottery finds, mostly from the Gulf and dated to the 5th to 8th century. The similarity to contemporary sites such as Mkokotoni and Dar es Salaam indicates a unified group of communities that developed into the first center of coastal maritime culture. The coastal towns appear to have been engaged in Indian Ocean and inland African trade at this early period.[18] Trade rapidly increased in importance and quantity beginning in the mid-8th century and by the close of the 10th century, Zanzibar was one of the central Swahili trading towns.[19]: 46

Excavations at nearby Pemba Island, but especially at Shanga in the Lamu Archipelago, provide the clearest picture of architectural development. Houses were originally built with timber (circa 1050) and later in mud with coral walls (circa 1150). The houses were continually rebuilt with more permanent materials. By the 13th century, houses were built with stone, and bonded with mud, and the 14th century saw the use of lime to bond stone. Only the wealthier patricians would have had stone- and lime-built houses, and the strength of the materials allowed for flat roofs. By contrast, the majority of the population lived in single-story thatched houses similar to those of the 11th and 12th centuries. According to John Middleton and Mark Horton, the architectural style of these stone houses have no Arab or Persian elements, and should be viewed as an entirely indigenous development of local vernacular architecture. While much of Zanzibar Town's architecture was rebuilt during Omani rule, nearby sites elucidate the general development of Swahili and Zanzibari architecture before the 15th century.[19]: 119

From the 9th century, Swahili merchants on Zanzibar operated as brokers for long-distance traders from both the hinterland and Indian Ocean world. Persian, Indian, and Arab traders frequented Zanzibar to acquire East African goods like gold, ivory, and ambergris and then shipped them overseas to Asia. Similarly, caravan traders from the African Great Lakes and Zambezian Region came to the coast to trade for imported goods, especially Indian cloth. Before the Portuguese arrival, the southern towns of Unguja Ukuu and Kizimkazi and the northern town of Tumbatu were the dominant centres of exchange. Zanzibar was just one of the many autonomous city-states that dotted the East African coast. These towns grew in wealth as the Swahili people served as intermediaries and facilitators to merchants and traders.[20] This interaction between Central African and Indian Ocean cultures contributed in part to the evolution of the Swahili culture, which developed an Arabic-script literary tradition. Although a Bantu language, the Swahili language as a consequence today includes some borrowed elements, particularly loanwords from Arabic, though this was mostly a 19th-century phenomenon with the growth of Omani hegemony. Many foreign traders from Africa and Asia married into wealthy patrician families on Zanzibar. Asian men in particular, who resided on the coast for up to six months because of the prevailing monsoon wind patterns, married East African women. Since almost all the Asian traders were Muslims, their children inherited their paternal ethnic identity, though East African matrilineal traditions remained key.[21][22]

Portuguese colonization

Vasco da Gama's visit in 1498 marked the beginning of European influence. In 1503 or 1504, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire when Captain Rui Lourenço Ravasco Marques came ashore and received tribute from the sultan in exchange for peace.[23]: 99 Zanzibar remained a possession of Portugal for almost two centuries. It initially became part of the Portuguese province of Arabia and Ethiopia and was administered by a governor-general. Around 1571, Zanzibar became part of the western division of the Portuguese empire and was administered from Mozambique.[24]: 15 It appears, however, that the Portuguese did not closely administer Zanzibar. The first English ship to visit Unguja, the Edward Bonaventure in 1591, found that there was no Portuguese fort or garrison. The extent of their occupation was a trade depot where produce was bought and collected for shipment to Mozambique. "In other respects, the affairs of the island were managed by the local 'king', the predecessor of the Mwinyi Mkuu of Dunga."[17]: 81 This hands-off approach ended when Portugal established a fort on Pemba Island around 1635 in response to the Sultan of Mombasa's slaughter of Portuguese residents several years earlier. Portugal had long considered Pemba to be a troublesome launching point for rebellions in Mombasa against Portuguese rule.[17]: 85

The precise origins of the sultans of Unguja are uncertain. However, their capital at Unguja Ukuu is believed to have been an extensive town. Possibly constructed by locals, it was composed mainly of perishable materials.[17]: 89

Sultanate of Zanzibar

The Portuguese arrived in East Africa in 1498, where they found several independent towns on the coast, with Muslim Arabic-speaking elites. While the Portuguese travellers describe them as "black", they made a clear distinction between the Muslim and non-Muslim populations.[26] Their relations with these leaders were mostly hostile, but during the sixteenth century, they firmly established their power and ruled with the aid of tributary sultans. The Portuguese presence was relatively limited, leaving administration in the hands of the local leaders and power structures already present. This system lasted until 1631, when the Sultan of Mombasa massacred the Portuguese inhabitants. For the remainder of their rule, the Portuguese appointed European governors. The strangling of trade and diminished local power led the Swahili elites in Mombasa and Zanzibar to invite Omani aristocrats to assist them in driving the Europeans out.[24]: 9

In 1698, Zanzibar came under the influence of the Sultanate of Oman.[27] There was a brief revolt against Omani rule in 1784. Local elites invited Omani merchant princes to settle in Zanzibar in the first half of the nineteenth century, preferring them to the Portuguese. Many locals today continue to emphasise that indigenous Zanzibaris had invited Seyyid Said, the first Busaidi sultan, to their island.[28] Claiming a patron–client relationship with powerful families was a strategy used by many Swahili coast towns from at least the fifteenth century.[28]

In 1832[23]: page: 162 or 1840[29]: 2 045 (the date varies among sources), Said bin Sultan, Sultan of Muscat and Oman moved his capital from Muscat, Oman to Stone Town. After Said's death in June 1856, two of his sons, Thuwaini bin Said and Majid bin Said, struggled over the succession. Said's will divided his dominions into two separate principalities, with Thuwaini to become the Sultan of Oman and Majid to become the first Sultan of Zanzibar; the brothers quarrelled about the will, which was eventually upheld by Charles Canning, 1st Earl Canning, Great Britain's Viceroy and Governor-General of India.[23]: pages: 163–4 [24]: 22–3

Until around 1890, the sultans of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of the Swahili coast known as Zanj, which included Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. Beginning in 1886, Great Britain and Germany agreed to allocate parts of the Zanzibar sultanate for their own empires.[29]: 188 In October 1886, a British-German border commission established the Zanj as a 10 nmi-wide (19 km) strip along most of the African Great Lakes region's coast, an area stretching from Cape Delgado (now in Mozambique) to Kipini (now in Kenya), including Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. Over the next few years most all of the mainland territory was incorporated into German East Africa. The sultans developed an economy of trade and cash crops in the Zanzibar Archipelago with a ruling Arab elite. Ivory was a major trade good. The archipelago, sometimes referred to by locals as the Spice Islands, was famous worldwide for its cloves and other spices, and plantations were established to grow them. The archipelago's commerce gradually fell into the hands of traders from the Indian subcontinent, whom Said bin Sultan encouraged to settle on the islands.

During his 14-year reign as sultan, Majid bin Said consolidated his power around the East African slave trade. Malindi in Zanzibar City was the Swahili Coast's main port for the slave trade with the Middle East. In the mid-19th century, as many as 50,000 slaves passed annually through the port.[30][31]

Many were captives of Tippu Tip, a notorious Arab/Swahili slave trader and ivory merchant. Tip led huge expeditions, some 4,000 strong, into the African hinterland where chiefs sold him their villagers at low prices. These Tip used to carry ivory back to Zanzibar, then sold them in the slave market for large profits. In time, Tip became one of the wealthiest men in Zanzibar, the owner of multiple plantations and 10,000 slaves.[30]

One of Majid's brothers, Barghash bin Said, succeeded him and was forced by the British to abolish the slave trade in the Zanzibar Archipelago. He largely developed Unguja's infrastructure.[32] Another brother of Majid, Khalifa bin Said, was the third sultan of Zanzibar and deepened the relationship with the British, which led to the archipelago's progress towards the abolition of slavery.[23]: 172

British protectorate

Control of Zanzibar eventually came into the hands of the British Empire; part of the political impetus for this was the 19th century movement for the abolition of the slave trade. Zanzibar was the centre of the East African slave trade. In 1822, Captain Moresby, the British consul in Muscat pressed Sultan Said to end the slave trade by signing a treaty.[33]

This Moresby Treaty was the first of a series of anti-slavery treaties with Britain. It prohibited slave transport south and east of the Moresby Line, from Cape Delgado in Africa to Diu Head on the coast of India.[34] Said lost the revenue he would have received as duty on all slaves sold, so to make up for this shortfall he encouraged the development of the slave trade in Zanzibar itself.[34] Said came under increasing pressure from the British to abolish slavery entirely. In 1842, Britain told Said it wished to abolish the slave trade to Arabia, Oman, Persia, and the Red Sea.[35]

Ships from the Royal Navy were employed to enforce the anti-slavery treaties by capturing any dhows carrying slaves, but with only four ships patrolling a huge area of sea, the British navy found it hard to enforce the treaties as ships from France, Spain, Portugal, and America continued to carry slaves.[36] In 1856, Sultan Majid consolidated his power around the African Great Lakes slave trade. But in 1873, Sir John Kirk informed his successor, Sultan Barghash, that a total blockade of Zanzibar was imminent, and Barghash reluctantly signed the Anglo-Zanzibari treaty which abolished the slave trade in the sultan's territories, closed all slave markets and protected liberated slaves.[37]

The relationship between Britain and the German Empire, at that time the nearest relevant colonial power, was formalized by the 1890 Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty, in which Germany agreed to "recognize the British protectorate over… the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba".[38]

In 1890, Zanzibar became a protectorate (not a colony) of Britain. This status meant it remained under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar. Prime Minister Salisbury explained the British position:

- The condition of a protected dependency is more acceptable to the half civilised races, and more suitable for them than direct dominion. It is cheaper, simpler, less wounding to their self-esteem, gives them more career as public officials, and spares them unnecessary contact with white men.[39]

From 1890 to 1913, traditional viziers were in charge; they were supervised by advisers appointed by the Colonial Office. In 1913, this was changed to direct rule through residents who were effectively governors. The death of the pro-British Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini on 25 August 1896 and the succession of Sultan Khalid bin Barghash, whom the British did not approve of, led to the Anglo-Zanzibar War. On the morning of 27 August 1896, ships of the Royal Navy destroyed the Beit al Hukum Palace. A cease-fire was declared 38 minutes later, and to this day the bombardment stands as the shortest war in history.[40]

Zanzibar revolution and merger with Tanganyika

On 10 December 1963,[41] the Protectorate that had existed over Zanzibar since 1890 was terminated by the United Kingdom. Rather, by the Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom, the UK ended the Protectorate and made provision for full self-government in Zanzibar as an independent country within the Commonwealth. Upon the Protectorate being abolished, Zanzibar became a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth under the Sultan.[42]

However, just a month later, on 12 January 1964 Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was deposed during the Zanzibar Revolution.[43] The Sultan fled into exile, and the Sultanate was replaced by the People's Republic of Zanzibar, a socialist government led by the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP). Over 20,000 people were killed – mostly Arabs and Indians – and many of them escaped the country as a consequence of the revolution.[44]

In April 1964, the republic merged with mainland Tanganyika. This United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar was soon renamed, blending the two names, as the United Republic of Tanzania, within which Zanzibar remains an autonomous region.

Demographics

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: 2002 data, 2 decades old. (May 2024) |

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 354,815 | — |

| 1977 | 476,111 | +2.98% |

| 1988 | 640,685 | +2.74% |

| 2002 | 984,625 | +3.12% |

| 2012 | 1,303,569 | +2.85% |

| 2022 | 1,889,773 | +3.78% |

| Source: [45][46] | ||

The 2022 census is the most recent census for which results have been reported. The total population of Zanzibar was 1,889,773 people – with an annual growth rate of 3.8 percent.[47] The population of Zanzibar City, which was the largest city, was 219,007.[48]

In 2002, around two-thirds of the people, 622,459, lived on Unguja (Zanzibar Island), with most settled in the densely populated west. Besides Zanzibar City, other towns on Unguja include Chaani, Mbweni, Mangapwani, Chwaka, and Nungwi. Outside of these towns, most people live in small villages and are engaged in farming or fishing.[49]

The population of Pemba Island was 362,166.[50] The largest town on the island was Chake-Chake, with a population of 19,283. The smaller towns are Wete and Mkoani.[49]

Mafia Island, the other major island of the Zanzibar Archipelago but administered by mainland Tanzania (Tanganyika), had a total population of 40,801.[51]

Ethnic origins

The people of Zanzibar are of diverse ethnic origins.[52] The first permanent residents of Zanzibar seem to have been the ancestors of the Bantu Hadimu and Tumbatu, who began arriving from the African Great Lakes mainland around AD 1000. They belonged to various mainland ethnic groups and on Zanzibar, generally lived in small villages. They did not coalesce to form larger political units.

During Zanzibar's brief period of independence in the early 1960s, the major political cleavage was between the Shirazi (Zanzibar Africans), who made up approximately 56% of the population, and the Zanzibar Arabs—the bulk of whom arrived from Oman in the 1800s—made up approximately 17%.[53][54] Today, Zanzibar is inhabited mostly by ethnic Swahili.[49] There are also a number of Arabs, as well as some ethnic Persian, Somalis, and Indian people.[55]

Languages

Swahili

Zanzibaris speak Swahili (Kiswahili), a Bantu language that is extensively spoken in the African Great Lakes region. Swahili is the de facto national and official language of Tanzania. Many local residents also speak Arabic, English, Italian and French.[56] The dialect of Swahili spoken in Zanzibar is called Kiunguja. Kiunguja, which has a high percentage of Arabic loanwords, enjoys the status of Standard Swahili not in Tanzania only but also in other countries, where Swahili is spoken.[57]

Arabic

Three distinct varieties of Arabic are in use in Zanzibar: Standard Arabic, Omani Arabic and Hadrami Arabic. Both vernacular varieties are falling out of use, although the Omani one is spoken by a larger group of people (probably, several hundreds). In parallel to this, Standard Arabic, traditionally associated with the Quran and Islam, is very popular not only among ethnic Arabs but also among Muslims of various descent who inhabit Zanzibar. Nevertheless, Standard Arabic is mastered by very few people. This can be attributed to the aggressive policy of Swahilisation. Despite the prestige and importance the Arabic language once enjoyed, today it is no longer the dominant spoken language.[57]

Religion

Zanzibar's population is almost entirely Muslim, with a small Christian minority of around 22 000.[58] Other religious groups include Hindus, Jains and Sikhs.[59]

The Anglican Diocese of Zanzibar was founded in 1892. The first Bishop of Zanzibar was Charles Smythies, who was translated from his former post as Bishop of Nyasaland.

Christ Church Cathedral had fallen into poor condition by the late 20th century, but it was fully restored in 2016, at a cost of one million Euros, with a world heritage visitor centre. The restoration was supported by the Tanzanian and Zanzibari governments, and overseen by the diocese in partnership with the World Monuments Fund.[60] The restoration of the spire, clock, and historic Willis organ are still outstanding. Historically the diocese included mainland locations in Tanganyika. In 1963, it was renamed as the Diocese of Zanzibar & Dar es Salaam. Two years later, in 1965, Dar es Salaam became a separate diocese. The original jurisdiction was renamed as the Diocese of Zanzibar & Tanga. In 2001, the mainland links were finally ended, and it is now known as the Diocese of Zanzibar. The diocese includes parishioners on the neighbouring island of Pemba. Ten bishops have served in the diocese from 1892 to the present day. The bishop is Michael Hafidh. It is part of the Province of Tanzania, under the Archbishop of All Tanzania, based at Dodoma.[61]

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Zanzibar, with its headquarters at the St. Joseph's Cathedral in Stone Town, was established in 1980. An apostolic vicariate of Zanzibar had been established in 1906, from a much larger East African jurisdiction. This was suppressed in 1953, when the territory was put under control of the Kenyan church, but it was restored in 1964 after independence. The church created a diocese here shortly before Easter 1980. The bishop is Augustine Ndeliakyama Shao. Zanzibar is part of the Roman Catholic Province of Dar es Salaam, under the Archbishop of Dar es Salaam.[62]

Other Christian denominations include the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania which arrived in Zanzibar town in the 1960s,[63] and a wide range of Pentecostal-Charismatic Christian churches such as the Tanzania Assemblies of God, the Free Pentecostal Church of Tanzania, the Evangelical Assemblies of God, the Pentecostal Church of Tanzania, the Victory Church and the Pentecostal Evangelistic Fellowship of Africa. Pentecostal-Charismatic churches have been present and growing in Zanzibar since the 1980s in relation to economic liberalization and increased labour migration from mainland Tanzania in connection to Zanzibar's expanding tourist sector. There are also Seventh Day Adventist and Baptist churches.[64]

Since 2005, there is also an inter-religious body called the Joint Committee of Religious Leaders for Peace (in Swahili Juhudi za Viongozi wa Dini kuimarisha Amani) with representatives from Muslim institutions such as the Islamic law (Kadhi courts), religious property (the Wakf and Trust commission), education (the Muslim academy) and the Mufti's office as well as representatives from the Roman Catholic, the Anglican and the Lutheran church.[65]

- Places of worship

The places of worship in the city are predominantly Muslim mosques.[66] There are also Christian churches and temples: Roman Catholic Diocese of Zanzibar (Catholic Church), Anglican Church of Tanzania (Anglican Communion), Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania (Lutheran World Federation), Baptist Convention of Tanzania (Baptist World Alliance), Assemblies of God.

Government

|

|---|

|

|

As an autonomous part of Tanzania, Zanzibar has its own government, known as the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar. It is made up of the Revolutionary Council and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives has a similar composition to the National Assembly of Tanzania. Fifty members are elected directly from constituencies to serve five-year terms; 10 members are appointed by the President of Zanzibar; 15 special seats are for women members of political parties that have representation in the House of Representatives; six members serve ex officio, including all regional commissioners and the attorney general.[67] Five of these 81 members are then elected to represent Zanzibar in the National Assembly.[68]

Zanzibar spans 5 of the 31 regions of Tanzania. Unguja has three administrative regions: Zanzibar Central/South, Zanzibar North and Zanzibar Urban/West. Pemba has two: Pemba North and Pemba South.[69]

Concerning the independence and sovereignty of Zanzibar, Tanzania Prime Minister Mizengo Pinda said on 3 July 2008 that there was "nothing like the sovereignty of Zanzibar in the Union Government unless the Constitution is changed in future". Zanzibar House of Representatives members from both the ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, and the opposition party, Civic United Front, disagreed and stood firmly in recognizing Zanzibar as a fully autonomous state.[70]

Politics

Zanzibar has a government of national unity, with the president of Zanzibar being Hussein Ali Mwinyi, since 1 November 2020. There are many political parties in Zanzibar, but the most popular parties are the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and the Civic United Front (CUF). Since the early 1990s, the politics of the archipelago have been marked by repeated clashes between these two parties.[71]

Contested elections in October 2000 led to a massacre on 27 January 2001 when, according to Human Rights Watch, the army and police shot into crowds of protestors, killing at least 35 and wounding more than 600. Those forces, accompanied by ruling party officials and militias, also went on a house-to-house rampage, indiscriminately arresting, beating, and sexually abusing residents. Approximately 2,000 temporarily fled to Kenya.[72]

Violence erupted again after another contested election on 31 October 2005, with the CUF claiming that its rightful victory had been stolen from it. Nine people were killed.[73][74]

Following 2005, negotiations between the two parties aiming at the long-term resolution of the tensions and a power-sharing accord took place, but they suffered repeated setbacks. The most notable of these took place in April 2008, when the CUF walked away from the negotiating table following a CCM call for a referendum to approve of what had been presented as a done deal on the power-sharing agreement.[75]

In November 2009, the then-president of Zanzibar, Amani Abeid Karume, met with CUF secretary-general Seif Sharif Hamad at the State House to discuss how to save Zanzibar from future political turmoil and to end the animosity between them.[76] This move was welcomed by many, including the United States.[77] It was the first time since the multi-party system was introduced in Zanzibar that the CUF agreed to recognize Karume as the legitimate president of Zanzibar.[76]

A proposal to amend Zanzibar's constitution to allow rival parties to form governments of national unity was adopted by 66.2 percent of voters on 31 July 2010.[78]

The autonomous status of Zanzibar is viewed as comparable to Hong Kong as suggested by some scholars, and with some recognizing the island as an "African Hong Kong".[79]

Nowadays, The Alliance for Change and Transparency-Wazalendois (ACT-Wazalendo) is considered the main opposition political party of semi-autonomous Zanzibar. The constitution of Zanzibar requires the party that comes in second in the polls to join a coalition with the winning party. ACT-Wazalendo joined a coalition government with the islands' ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi in December 2020 after Zanzibar disputed elections.[80]

Geography

Zanzibar is one of the Indian Ocean islands. It is situated on the Swahili Coast, adjacent to Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania).

The northern tip of Unguja island is located at 5.72 degrees south, 39.30 degrees east, with the southernmost point at 6.48 degrees south, 39.51 degrees east.[81] The island is separated from the Tanzanian mainland by a channel, which at its narrowest point is 36.5 km (22.7 mi) across.[82] The island is about 85 km (53 mi) long and 39 km (24 mi) wide,[82] with an area of 1,464 km2 (565 sq mi).[83] Unguja is mainly low lying, with its highest point being 120 m (390 ft).[83] Unguja is characterised by beautiful sandy beaches with fringing coral reefs.[83] The reefs are rich in marine biodiversity.[84]

The northern tip of Pemba island is located at 4.87 degrees south, 39.68 degrees east, and the southernmost point is located at 5.47 degrees south, 39.72 degrees east.[81] The island is separated from the Tanzanian mainland by a channel some 56 km (35 mi) wide.[82] The island is about 67 km (42 mi) long and 23 km (14 mi) wide, with an area of 985 km2 (380 sq mi).[82] Pemba is also mainly low lying, with its highest point being 95 m (312 ft).[85]

Climate

Zanzibar has a tropical monsoon climate (Am). The heat of summer (corresponding to the Northern Hemisphere winter) is often cooled by strong sea breezes associated with the northeast monsoon (known as Kaskazi in Kiswahili), particularly on the north and east coasts. Being near to the equator, the islands are warm year round. The rainfall regime is split into two main seasons, a primary maximum in March, April, and May in association with the southwest monsoon (known locally as Kusi in Kiswahili), and a secondary maximum in November and December.[86] The months in between receive less rain, with a minimum in July.

| Climate data for Zanzibar City | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 33.4 (92.1) |

34.1 (93.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

31.7 (89.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.5 (83.3) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28 (82) |

26.9 (80.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69 (2.7) |

65 (2.6) |

152 (6.0) |

357 (14.1) |

262 (10.3) |

59 (2.3) |

45 (1.8) |

44 (1.7) |

51 (2.0) |

88 (3.5) |

177 (7.0) |

143 (5.6) |

1,512 (59.5) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[87] | |||||||||||||

Wildlife

Unguja

The main island of Zanzibar, Unguja, has a fauna reflecting its connection to the African mainland during the last Ice Age.[88][89]

Endemic mammals with continental relatives include the Zanzibar red colobus (Procolobus kirkii), one of Africa's rarest primates, with perhaps only 1,500 existing. Isolated on this island for at least 1,000 years, this colobus is recognized as a distinct species, with different coat patterns, calls, and food habits from related colobus species on the mainland.[90] The Zanzibar red colobus lives in a wide variety of drier areas of coastal thickets and coral rag scrub, as well as mangrove swamps and agricultural areas. About one third of them live in and around Jozani Forest. The easiest place to see the colobus is farmland adjacent to the reserve. They are accustomed to people and the low vegetation means they come close to the ground.

Rare native animals include the Zanzibar leopard,[10][11] which is critically endangered, and the recently described Zanzibar servaline genet. There are no large wild animals in Unguja. Forested areas such as Jozani are inhabited by monkeys, bushpigs, small antelopes, African palm civets, and, as shown by a camera trap in June 2018,[10][11] the elusive leopard. Various species of mongoose can also be found on the island. There is a wide variety of birdlife and a large number of butterflies in rural areas.[citation needed]

Pemba

Pemba Island is separated from Unguja island and the African continent by deep channels and has a correspondingly restricted fauna, reflecting its comparative isolation from the mainland.[88][89] The island is home to the Pemba flying fox.

Standard of living and health

Considerable disparities exist in the standard of living for inhabitants of Pemba and Unguja, as well as the disparity between urban and rural populations. The average annual income is US $2500. About half the population lives below the poverty line.

Despite a relatively high standard of primary health care and education, infant mortality in Zanzibar is 54 out of 1,000 live births, which is 10.0 percent lower than the rate in mainland Tanzania. The child mortality rate in Zanzibar is 73 out of 1,000 live births, which is 21.5 percent lower than the rate in mainland Tanzania.[91] The birth rate in Tanzania in 2021 is high, 35.64 births per 1000 population, but the rate is falling.[92]

It is estimated that 7% of children on Zanzibar have acute malnutrition.[93]

Life expectancy at birth is 57 years,[94] which is significantly lower than the 2010 world average of 67.2.

The general prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the population of Zanzibar aged 15–64 is 0.5 percent, with the rate much higher in females (0.9 percent) than males (less than 0.1 percent).[95]

Environment

The northern part of the island presents elevated volumes of trash in the streets, beaches and the ocean—mostly plastic bottles, other plastics and cigarette butts. There is indiscriminate dumping in residential areas. Medical equipment waste is a particular problem on the island.[96]

Climate change impact

Studies conducted show temperatures and wind speeds have increased strongly over the last 40 years. These climatic stressors, in addition to the changes in rainfall patterns have had significant effects on the seaweed farming, causing seaweed to rot or be destroyed in the process of yielding.[97]

Economy

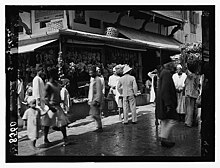

Ancient pottery implies trade routes with Zanzibar as far back as the time of the ancient Assyrians. Traders from the Arabian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf region of modern-day Iran (especially Shiraz), and west India probably visited Zanzibar as early as the 1st century. They used the monsoon winds to sail across the Indian Ocean to land at the sheltered harbor located on the site of present-day Zanzibar City.[citation needed]

The clove, originating from the Moluccan Islands (today in Indonesia), was introduced in Zanzibar by the Omani sultans in the first half of the 19th century.[98] Zanzibar, mainly Pemba Island, was once the world's leading clove producer,[99] but annual clove sales have plummeted by 80 percent since the 1970s. Zanzibar's clove industry has been crippled by a fast-moving global market, international competition, and a hangover from Tanzania's failed experiment with socialism in the 1960s and 1970s, when the government controlled clove prices and exports. Zanzibar now ranks a distant third with Indonesia supplying 75 percent of the world's cloves compared to Zanzibar's 7 percent.[99]

Zanzibar exports spices, seaweed and fine raffia.[100] Research into the economic potential of seaweed farming was undertaken by Adelaida K. Semesi from 1982 until her death in 2001.[101] Beside the Zanzibar State Trading Cooperation, Zanj Spice Limited, also known as 1001 Organic, is the biggest organic spice exporter in Zanzibar.[100] Zanzibar also has a large fishing and dugout canoe production. Tourism is a major foreign currency earner.[102]

The Government of Zanzibar legalized foreign exchange bureaux on the islands before mainland Tanzania moved to do so. The effect was to increase the availability of consumer commodities. The government has also established a free port area, which provides the following benefits: contribution to economic diversification by providing a window for free trade as well as stimulating the establishment of support services; administration of a regime that imports, exports, and warehouses general merchandise; adequate storage facilities and other infrastructure to cater for effective operation of trade; and creation of an efficient management system for effective re-exportation of goods.[103]

The island's manufacturing sector is limited mainly to import substitution industries, such as cigarettes, shoes, and processed agricultural products. In 1992, the government designated two export-producing zones and encouraged the development of offshore financial services. Zanzibar still imports much of its staple requirements, petroleum products, and manufactured articles.[citation needed]

There is also a possibility of oil availability in Zanzibar on the island of Pemba, and efforts have been made by the Tanzanian government and Zanzibar revolutionary government to exploit what could be one of the most significant discoveries in recent memory. Oil would help boost the economy of Zanzibar,[citation needed] but there have been disagreements about dividends between the Tanzanian mainland and Zanzibar, the latter claiming the oil should be excluded in Union matters.[104]

In 2007, a Norwegian consultancy firm went to Zanzibar to determine how the region could develop its oil potential.[105] The firm recommended that Zanzibar follow economist Hernando de Soto Polar's ideas about the formalization of property rights for persons living on ancestral land for which they probably do not have a legal deed.[106]

Tourism

Tourism in Zanzibar includes the tourism industry and its effects on the islands of Unguja (known internationally as Zanzibar) and Pemba in Zanzibar a semi-autonomous region in the United Republic of Tanzania.[107] Tourism is the top income generator for the islands, outpacing even the lucrative agricultural export industry and providing roughly 25% of income.[108][109] The main airport on the island is Zanzibar International Airport, though many tourists fly into Dar es Salaam and take a ferry to the island.

The Government of Zanzibar plays a major role in promoting the industry. Zanzibar Commission for Tourism recorded more than doubling the number of tourists from the 2015/2016 fiscal year and the following year, from 162,242 to 376,000.[110]

The increase in tourism has led to significant environmental impacts and mixed impacts on local communities, which were expected to benefit from economic development but in large part have not.[109][111] Communities have witnessed increasing environmental degradation, and that flow of tourists has reduced the access of local communities to the marine and coastal resources that are the center of tourist activity.[109]Energy

The energy sector in Zanzibar consists of unreliable electric power, petroleum and petroleum products; it is also supplemented by firewood and its related products. Coal and gas are rarely used for either domestic or industrial purposes.

Unguja (Zanzibar Island) gets most of its electric power from mainland Tanzania through a 39-kilometer, 100-megawatt submarine cable from Ras Kiromoni (near Dar es Salaam) to Ras Fumba on Unguja. The laying of the cable was begun on 10 October 2012 by the Viscas Corporation of Japan and was funded by a US$28.1 million grant from the United States through the Millennium Challenge Corporation.[112][113] The cable became operational on 13 April 2013.[114] The previous 45-megawatt cable, which was seldom-maintained, was completed by Norway in 1980.[citation needed]

Since May 2010, Pemba Island has had a 75 km (47 mi), 25-megawatt, subsea electrical link directly to mainland Tanzania. The cable project was financed through a 45 million euro grant from Norway and contributions of 8 million euros from the Zanzibar government and 4 million euros from the Tanzanian national government. The project ended years of dependence on unreliable and erratic diesel generation subject to frequent power cuts. Only about 20 percent of the cable's capacity was being used in January 2011, so it is anticipated that the cable will meet the island's needs for 20 to 25 years.[115][116]

Between 70 and 75 percent of the electricity generated is used domestically while less than 20 percent is used industrially. Fuel wood, charcoal and kerosene are widely used as sources of energy for cooking and lighting for most rural and urban areas. The consumption capacity of petroleum, gas, oil, kerosene and industrial diesel oil is increasing annually, going from a total of 5,650 tons consumed in 1997 to more than 7,500 tons in 1999.[citation needed]

From 21 May to 19 June 2008, Unguja suffered a major failure of its electricity system, which left the island without electrical service and mostly dependent on diesel generators. The failure originated in mainland Tanzania.[117] Another blackout happened from 10 December 2009 to 23 March 2010, caused by a problem with the submarine cable that formerly supplied electricity from mainland Tanzania.[118] This led to a serious shock to Unguja's fragile economy, which is heavily dependent on foreign tourism.

Transport

Roads

Zanzibar has 1,600 kilometres (990 miles) of roads, of which 85 percent are sealed or partly-sealed tarmac. The remainder are gravel roads, which are rehabilitated annually to make them passable throughout the year.[citation needed] Zanzibar has a Road Fund Board, situated at Maisala which collects funds and disburses to the Ministry of Communication, which is the Road Agency at this time through the Department of Road Maintenance, known as UUB.

The Road Fund Board oversees a Performance Agreement entered between the Ministry of Communication and Infrastructure, while procurement and maintenance are assumed by the latter.[citation needed]

Public transportation

There is no government-owned public transportation in Zanzibar. The privately owned Daladala, as it is officially known in Zanzibar, is the only kind of public transportation. The term Daladala originated from the Kiswahili word DALA (Dollar) or five shillings during the 1970s and 1980s when public transport cost five shillings to travel to the nearest town. Therefore, travelling to town will cost a Dollar ("Dala") and returning will again cost a Dollar, hence the term Daladala originated.[119]

Stone Town is the main hub for Daladalas on Zanzibar and nearly all journeys will either start or end here. There are two main Dala Dala stations in Stone Town: Darajani market and Mwanakwerekwe market. The Darajani market terminus serves the North and North East of the island and the Mwanakwerekwe market terminus serves the South and South East. As with most of East African transport, the buses do not run on set schedules – instead departing when full. As there is no fixed schedule, it is not possible to book tickets in advance (with the exception of The Zanzibus). There are plans to implement a government-operated bus service on the island, which will bring the ground transportations more in line with the relatively developed water and air transport infrastructure. With Zanzibar visitor numbers set to exceed 1,000,000 annually, there will be increasing pressure on the current transportation network – the bus network will reduce the number of vehicles on the road and help reduce environmental impact of tourism on Zanzibar.

Maritime transport

Ports

There are five ports in the islands of Unguja and Pemba, all operated and developed by the Zanzibar Ports Corporation.

The main port at Malindi, which handles 90 percent of Zanzibar's trade, was built in 1925. The port was rehabilitated between 1989 and 1992 with financial assistance from the European Union. The Italian contractor, Salini Impregilo S.p.A., was supposed to build wharves that lasted 60 years; however, the wharves lasted only 11 years before crumbling and degenerating because the company deviated from the specifications by using poor quality material.[120] After a long legal battle, the company was required in 2005 by the International Court of Arbitration to pay Zanzibar US$11.6 million in damages.[121] The port was again rehabilitated between 2004 and 2009 with a 31 million euro grant from the European Union. The contract was awarded to M/S E. Phil and Sons of Denmark. The then-director of the contractor suggested that the rehabilitation would last a minimum of 50 years. But the port is again facing problems, including sinking.[120] A new dedicated passenger port is planned to be constructed in Mpigaduri as a public–private partnership.[122]

- Ferry accidents

The MV Faith, which began its final journey at the port of Dar es Salaam, sank in May 2009 shortly before docking at the port of Malindi. Six of the 25 people aboard lost their lives.[123]

The sinking of the MV Spice Islander I on 10 September 2011, after departing from Unguja island for Pemba Island, was the worst disaster in Tanzanian history. In a report to the Zanzibar House of Representatives on 14 October 2011, Zanzibar's Second Vice President, Ambassador Seif Ali Iddi, said that 2,764 people were missing, 203 bodies had been recovered, and 619 passengers were rescued. It was the worst maritime disaster in Tanzanian history.[124] A presidential commission, however, reported three months later that 1,370 people were missing, 203 bodies had been recovered, and 941 passengers survived. Severe overloading caused the ferry to sink.[125]

The MV Skagit, which began its final journey at the port of Dar es Salaam, capsized in rough seas near Chumbe island on 18 July 2012. The ferry had 447 passengers, with 81 dead, 212 missing and presumed drowned, and 154 rescued. The ferry left port despite warnings from the Tanzania Meteorological Agency for ships not to attempt the crossing from Dar es Salaam to Unguja island because of the rough seas. A presidential commission reported in October 2012 that overloading was the cause of the disaster.[126][127]

Airport

Zanzibar's main airport, Abeid Amani Karume International Airport, has been able to handle large passenger planes since 2011, which has resulted in an increase in passenger and cargo inflows and outflows. Since another increase in capacity by the end of 2013, it can serve up to 1.5 million passengers per year.[9] The island can be reached by flights operated by Air France, Auric Air,[128] Air Tanzania, Coastal Aviation,[129] Ethiopian Airlines,[130] Kenya Airways,[131] FlyDubai, Qatar Airways, Turkish Airlines and others.

Culture

Zanzibar's most famous event is the Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF), also known as the Festival of the Dhow Countries. Every July, this event showcases the best of the Swahili Coast arts scene, including Zanzibar's favorite music, taarab.[citation needed] Zanzibar is the birthplace of the British singer-songwriter and band leader of Queen, Freddie Mercury.

Important architectural features in Stone Town are the Livingstone house, The Old dispensary of Zanzibar, the Guliani Bridge, Ngome kongwe (The Old fort of Zanzibar) and the House of Wonders.[132] The town of Kidichi features the Hamamni Persian Baths, built by immigrants from Shiraz, Iran during the reign of Barghash bin Said.

Zanzibar also is the only place in Eastern African countries to have the long settlement houses formally known as Michenzani flats. The flats were built with aid from East Germany during the 1970s to solve housing problems in Zanzibar.[133]

Media and communication

In 1973, Zanzibar introduced the first colour television service in sub-Saharan Africa.[134] Because of longstanding opposition to television by President Julius Nyerere, the first television service on mainland Tanzania was not introduced until 1994.[135] The broadcaster in Zanzibar called Television Zanzibar (TVZ) had recently changed name to Zanzibar Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC).[136] following an enactment of an act to make it a public corporation, monitored under the Ministry of Finance by the treasurer registrar. Among the famous reporters of TVZ during the 1980s and 1990s were the late Alwiya Alawi 1961–1996 (the elder sister of Inat Alawi, famous Taarab singer during the 1980s), Neema Mussa, Sharifa Maulid, Fatma Mzee, Zaynab Ali, Ramadhan Ali, and Khamis.[citation needed]

Zanzibar has one AM radio station[137] and 21 FM radio stations.[138]

In terms of landline communications, Zanzibar is served by the Tanzania Telecommunications Company Limited and Zantel Tanzania.

Almost all mobile and Internet companies serving mainland Tanzania are also available in Zanzibar.

Education

In 2000, there were 207 government schools and 118 privately owned schools in Zanzibar.[139] Zanzibar has three fully accredited Universities: Zanzibar University, the State University of Zanzibar (SUZA) and Sumait University (previously University College of Education, Chukwani).[140]

SUZA was established in 1999, and is located in Stone Town, in the buildings of the former Institute of Kiswahili and Foreign Language (TAKILUKI).[141] It is the only public institution for higher learning in Zanzibar, the other two institutions being private. In 2004, the three institutions had a total enrollment of 948 students, of whom 207 were female.[142]

The primary and secondary education system in Zanzibar is slightly different from that of the Tanzanian mainland. On the mainland, education is only compulsory for the seven years of primary education, while in Zanzibar an additional three years of secondary education are compulsory and free.[139] Students in Zanzibar score significantly less on standardized tests for reading and mathematics than students on the mainland.[139][143]

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, national service after secondary education was necessary, but it is now voluntary and few students volunteer. Most choose to seek employment or attend teacher's colleges.

The IIT Madras set up a campus in Zanzibar, which began classes for the first batch in November 2023.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Zanzibar, overseen by the Zanzibar Football Association.[144] Zanzibar is an associate member of the Confederation of African Football (CAF), but not of FIFA. This means that the Zanzibar national football team is not eligible to enter national CAF competitions, such as the African Nations Cup, but Zanzibar's football clubs get representation at the CAF Confederation Cup and the CAF Champions League.

The national team participates in non-FIFA Football tournaments such as the FIFI Wild Cup, and the ELF Cup. Because Zanzibar is not a member of FIFA, their team is not eligible for the FIFA World Cup.

The Zanzibar Football Association also has a Premier League for the top clubs, which was created in 1981. The teams also participate in the FA knockout competition, Zanzibari Cup and the Mapinduzi Cup, a knockout competition organized in early January between 6–13 January to mark the revolution day (12 January).[145]

Cricket was historically popular in Zanzibar. In the 1950s and 1960s, the island hosted touring teams from England, India, Pakistan, South Africa and Uganda,[146] but the sport declined following the 1964 revolution. Zanzibar contributed some players to the East Africa cricket team in the late 20th century. Efforts to revive the game in the 21st century have been led by Indian firms, with plans announced in 2022 for an international-grade cricket ground in Fumba with the support of the Zanzibar government.[147]

Since 1992, there has also been judo in Zanzibar. The founder, Tsuyoshi Shimaoka, established a team that participates in national and international competitions. In 1999, Zanzibar Judo Association (Z.J.A.) was registered and became an active member of the Tanzania Olympic Committee [citation needed] and International Judo Federation.

Notable people

- Samia Suluhu Hassan, President of Tanzania since 19 March 2021

- Said Salim Bakhresa, billionaire business tycoon born in Zanzibar, chairperson of Bakhresa Group of Companies

- Abdulrazak Gurnah, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature; born in Zanzibar in 1948 and emigrated to Britain as a student in 1968[148][149]

- Lubaina Himid, artist and winner of the 2017 Turner Prize, born 1954

- Salama Jabir, journalist, TV host, media entertainer

- Javed Jafferji, award-winning photographer and publisher; received the Almanacs Top 100 Africans for his work in promoting Africa worldwide[150][151]

- Bi Kidude, Taarab singer of Taarab and Unyago music, received WOMEX award in 2005

- Faruk Malik, Ugandan official and spy under Idi Amin

- Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara), British singer of the rock band Queen, born in Stone Town;[152] at the age of 17, fled with his family to the United Kingdom during the Zanzibar Revolution[153]

- Siti binti Saad, pioneering artist in Taarab

Gallery

-

Stone Town

-

Stone Town with Sultan's Palace

-

House of Wonders undergoing refurbishment

-

Cloves have played a significant role in Zanzibar's historic economy.

-

The red colobus of Zanzibar (Procolobus kirkii), taken at Jozani Forest

-

Zanzibar East Coast beach

-

Red-knobbed starfish (Protoreaster linckii) on the beach in Nungwi, northern Zanzibar

-

A Zanzibar beach

-

Cannons overlooking the water at Forodhani Gardens park, in Stone Town

-

A five-star resort on the northern part of Zanzibar

-

An Arabic and Indian style door in Zanzibar

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Kendall, David (2014). "Zanzibar". nationalanthems.info. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "President's Office and Chairman of Revolutionary Council, Zanzibar". President of Zanzibar. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Country Profile Area and Population". Embassy of the United Republic of Tanzania in Rome. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Zanzibar". www.ushnirs.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ "Exotic Zanzibar and its seafood". 21 May 2011. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Lange, Glenn-Marie (1 February 2015). "Tourism in Zanzibar: Incentives for sustainable management of the coastal environment". Ecosystem Services. Marine Economics and Policy related to Ecosystem Services: Lessons from the World's Regional Seas. 11: 5–11. Bibcode:2015EcoSv..11....5L. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.11.009. ISSN 2212-0416.

- ^ Yussuf, Issa (19 April 2017). "Tanzania: Number of Tourists to Zanzibar Doubles As Tourist Hotels Improve Service Delivery". allAfrica. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Zanzibar forms Airports Authority, modernises aviation infrastructure". Business Times (Tanzania). Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Li, Joanna (7 June 2018). "Zanzibar Leopard Captured on Camera, Despite Being Declared Extinct". Inside Edition. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Seaburn, Paul (12 June 2018). "Extinct 'Evil' Zanzibar Leopard Seen Alive in Tanzania". Mysterious Universe. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Khamis, Zakaria A.; Kalliola, Risto; Käyhkö, Niina (15 November 2017). "Geographical characterization of the Zanzibar coastal zone and its management perspectives". Ocean & Coastal Management. 149: 116–134. Bibcode:2017OCM...149..116K. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.10.003. ISSN 0964-5691. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "zanzibar". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Richard F. Burton (2010). The Lake Regions of Central Africa. New York: Cosimo, Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-61640-179-5.

- ^ Mehrdad Shokoohy (2013). Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma'bar and the Traditions of Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa). New York: Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-136-49977-7. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Hashim, Nadra O. (2009). Language and Collective Mobilization: The Story of Zanzibar. Lexington Books. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-73913708-6. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Pearce, Francis Barrow (1920). Zanzibar: The Island Metropolis of Eastern Africa. New York City: Dutton & Com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Kusimba, Chapurukha; Walz, Jonathan (2018). "When did the Swahili become Maritime?: A Reply to Fleisher et al. (2015), and to the Resurgence in Maritime Myopia in the Archaeology of the East African Coast". American Anthropologist. 120 (3): 100–115. doi:10.1111/aman.12171. PMC 4368416. PMID 25821235.

- ^ a b Horton, Mark; Middleton, Tom (2001). The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Community. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63118919-0.

- ^ Kusimba, Chapurukha (1999). The Rise and Decline of Swahili States. Walnut Creek, California: Altamira. ISBN 9780761990512.

- ^ Campbell, Gwynn (2019). Africa and the Indian Ocean World from Early Times to Circa 1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10857862-2.

- ^ Wynne-Jones, Stephanie; LaViolette, Adria (2018). The Swahili World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13891346-2.

- ^ a b c d Ingrams, W. H. (1 June 1967). Zanzibar: Its History and Its People. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-71461102-0. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Sir Charles Eliot, K.C.M.G., The East Africa Protectorate, London: Edward Arnold, 1905, digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 (PDF format).

- ^ "The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar". Chronicles of the London Missionary Society. 1890. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Prestholdt, Jeremy. "Portuguese Conceptual Categories and the ‘Other’ Encounter on the Swahili Coast." Journal of Asian American Studies, Volume 36, Issue 4, 390.

- ^ N. S. Kharusi, "The ethnic label Zinjibari: Politics and language choice implications among Swahili speakers in Oman" Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Ethnicities, 12(3) 335–53, 2012.

- ^ a b Meier, Sandy Prita (25 April 2016). Swahili Port Cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 103.

- ^ a b Appiah; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (1999), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00071-1, OCLC 41649745

- ^ a b "Swahili Coast: East Africa's Ancient Crossroads"Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Did You Know? sidebar by Christy Ullrich, National Geographic.

- ^ Borders, Everett (2010). Apart Type Screenplay. United States of America: Xlibris Corporation. p. 117.

- ^ Michler, Ian (2007), Zanzibar: The Insider's Guide (2nd ed.), Cape Town: Struik Publishers, p. 137, ISBN 978-1-77007-014-1, OCLC 165410708

- ^ Sherif, Abdul (1987). "Athens". Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Coast into the World Economy, 1770–1873. Ohio University Press.

- ^ a b Chris McIntyre, Susan McIntyre (2013). Zanzibar, Bradt Travel Guides, p. 10.

- ^ McIntyre & McIntyre, p. 13.

- ^ McIntyre & McIntyre, p. 14.

- ^ McIntyre & McIntyre, p. 19.

- ^ Article XI, Anglo-German Treaty (Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty) Archived 23 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 1 July 1890 (PDF).

- ^ Andrew Roberts, Salisbury: Victorian Titan (1999) p 529

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (7 August 2007). Guinness World Records 2008. London: Guinness World Records. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-904994-19-0.

- ^ Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom – this Act was not a Zanzibar Independence Act because the UK was not conferring independence as it did not hold sovereignty; it was ending the Protectorate over that territory and providing for its fully responsible government.

- ^ United States Department of State 1975, p. 986

- ^ Ayany 1970, p. 122.

- ^ "The forgotten genocide of the Zanzibar revolution". Speak Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Tanzania: Regions and Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Tanzania: Regions and Cities – Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ 2022 Census: Administrative Units Population Distribution Report (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1C. Ministry of Finance and Planning, National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania. December 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Mjini Municipal". citypopultation.de. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "People and Culture – Zanzibar Travel Guide". Zanzibar-travel-guide.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "2002 Population and Housing Census General Report: Pemba". Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.

- ^ "2002 Population and Housing Census General Report: Mafia". Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.

- ^ "Zanzibar People and Culture". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ GROWup – Geographical Research on War, Unified Platform. "Ethnicity in Zanzibar". ETH Zurich. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Sheriff, Abdul (2001). "Race and Class in the Politics of Zanzibar". Africa Spectrum. 36 (3): 301–318. JSTOR 40174901.

- ^ Tanzania (08/09) Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine . U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Chris McIntyre and Susan McIntyre, "Zanzibar, Pemba, and Mafia" Archived 12 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Bradt Travel Guide, 2009, p. 36.

- ^ a b Sarali Gintsburg (2018) Arabic language in Zanzibar: past, present, and future, Journal of World Languages, 5:2, 81–100, doi:10.1080/21698252.2019.1570663.

- ^ a b "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Keshodkar, Akbar (29 March 2010). "Marriage as the Means to Preserve 'Asian-ness': The Post-Revolutionary Experience of the Asians of Zanzibar". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 45 (2): 226–240. doi:10.1177/0021909609357418. ISSN 0021-9096. S2CID 143909800.

- ^ Progress report and photographs at this Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine webpage.

- ^ Mndolwa, Maimbo; Denis, Philippe (November 2016). "Anglicanism, Uhuru and Ujamaa: Anglicans in Tanzania and the Movement for Independence". Journal of Anglican Studies. 14 (2): 192–209. doi:10.1017/S1740355316000206. ISSN 1740-3553.

- ^ "Historical Background". Dar es Salaam Archdiocese. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Sicard, Sigvard von. (1970). The Lutheran Church on the coast of Tanzania, 1887–1914 : with special reference to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania, Synod of Uzaramo-Uluguru. Gleerup. OCLC 1100148145.

- ^ Olsson, Hans (4 July 2019), "Narratives of Pentecostal (Non-)Belonging", Jesus for Zanzibar: Narratives of Pentecostal (Non-)Belonging, Islam, and Nation, BRILL, pp. 224–233, doi:10.1163/9789004410367_008, ISBN 978-90-04-40681-0, S2CID 204477650

- ^ Langås, Arngeir (12 April 2019). Peace in Zanzibar. Peter Lang US. doi:10.3726/b14434. ISBN 978-1-4331-5969-5. S2CID 188527686.

- ^ Britannica, Tanzania Archived 18 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 5 January 2020

- ^ "Composition". The House of Representatives – Zanzibar. Retrieved 23 October 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Composition, Parliament of Tanzania Archived 21 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tanzania Regions". www.statoids.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Zanzibar: Premier under fire on Zanzibar status". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. 10 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Throup, David W. (18 March 2016). "The Political Crisis in Zanzibar". Center for strategic and international studies. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Tanzania: Zanzibar Election Massacres Documented". Human Rights Watch. 10 April 2002. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Nine killed in Zanzibar election violence", The Seattle Times, reported by Chris Tomlinson, The Associated Press, 1 November 2005 Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Zimbabwe Farm Evictions 2000". karelprinsloo karel prinsloo. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Tanzanian Affairs » ZANZIBAR – A BIG DISAPPOINTMENT". www.tzaffairs.org. May 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b ""Karume: No elections next year in Zanzibar if…", Zanzibar Institute for Research and Public Policy, reported by Salma Said, reprinted from an original article in The Citizen, 19 November 2009". 19 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to VPP Zanzibar, Tanzania". United States Virtual Presence Post. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Zanzibar: 2010 Constitutional referendum results" Archived 5 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa, updated August 2010.

- ^ Simon Shen, One country, two systems: Zanzibar, Ming Pao Weekly, Sep 2016.

- ^ "Zanzibar's opposition party to join coalition government". Associated Press. 6 December 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Find Latitude and Longitude". www.findlatitudeandlongitude.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Sharaf, Yasir (9 July 2017). "The Allure Of Zanzibar Island | Zanzibar Tourism And Economic Climate". XPATS International. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Africa Guide – Zanzibar". web page. africaguide.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ Molly Moynihan, "Water Quality and Eutrophication: The Effects of Sewage Outfalls on Waters and Reefs Surrounding Stone Town, Zanzibar" Archived 9 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Independent Study Project Collection, 2010, p. 8.

- ^ ""Tanzania: Zanzibar and Pemba", Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Climate and Soils". Zanzinet Forum. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Zanzibar City". Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ a b Pakenham, R. H. W. (1984). The Mammals of Zanzibar and Pemba Islands. Harpenden: privately printed. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b Walsh, Martin T. (2007). "Island Subsistence: Hunting, Trapping and the Translocation of Wildlife in the Western Indian Ocean". Azania. 42: 83–113. doi:10.1080/00672700709480452. S2CID 162594865. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Red Colobus". galenfrysinger.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010", National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, published April 2011, page 120 Archived 10 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine (PDF format).

- ^ "Crude birth rate (births per 1000 population)". World Health Organisation. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2015–2016 – Final Report" (PDF). DHS Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Zanzibar: Social Protection Expenditure and Performance Review and Social Budget", Social Security Department, International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland, January 2010, page 22

- ^ Tanzania HIV Impact Survey (THIS) 2016–2017: Final Report (PDF) (Report). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS). December 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "IJCRAR" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ de Jong Cleynder, Georgia (April 2021). "Adaptation of Seaweed Farmers in Zanzibar to the Impacts of Climate Change". African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_54-1. ISBN 978-3-030-42091-8.

- ^ Professor Trevor Marchand. Oman & Zanzibar: The Sultans of Oman Archived 31 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Archaeological Tours.

- ^ a b Sanders, Edmund (24 November 2005). "Zanzibar Loses Some of Its Spice". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b Brohm, Annika. "Wo der Bio-Pfeffer wächst". faz.net. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Oliveira, E. C.; Österlund, K.; Mtolera, M. S. P. (2003). Marine Plants of Tanzania. A field guide to the seaweeds and seagrasses of Tanzania. Sida/Department for Research Cooperation, SAREC. pp. Dedication.

- ^ "Zanzibar Then and Now". zanzibarholidays.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Bureau of African Affairs (8 June 2010). "Background Note: Tanzania". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Economy". ft.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". thecitizen.co.tz. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chambi Chachage, "Norway in Tanzania: The Battle Rages"[better source needed] Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The African Executive.

- ^ Sharpley, Richard; Ussi, Miraji (January 2014). "Tourism and Governance in Small Island Developing States (SIDS): The Case of Zanzibar: Tourism and Governance in Zanzibar". International Journal of Tourism Research. 16 (1): 87–96. doi:10.1002/jtr.1904.

- ^ Zanzibar islands ban plastic bags BBC News, 10 April 2006

- ^ a b c Lange, Glenn-Marie (1 February 2015). "Tourism in Zanzibar: Incentives for sustainable management of the coastal environment". Ecosystem Services. Marine Economics and Policy related to Ecosystem Services: Lessons from the World’s Regional Seas. 11: 5–11. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.11.009. ISSN 2212-0416.

- ^ Yussuf, Issa (19 April 2017). "Tanzania: Number of Tourists to Zanzibar Doubles As Tourist Hotels Improve Service Delivery". allAfrica. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Rotarou, Elena (December 2014). "Tourism in Zanzibar: Challenges for pro-poor growth". Caderno Virtual Dde Tourismo. 14 (3): 250–265.

- ^ "Ambassador Lenhardt Participates in Ceremony to Install 100 Megawatt Submarine Power to Zanzibar" Archived 17 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Press Release, Embassy of the United States, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 10 October 2012.

- ^ 132kV Sabmarine Cable – Zanzibar Iterconnector at Ras Kiromoni and Ras Fumba Archived 28 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Featured Project, Salem Construction, Ltd.

- ^ Yussuf, Issa (24 April 2013). "Tanzania: Reliable Power to Accelerate Development in Isles President Ali" Archived 9 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Daily News (via AllAfrica.com). Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Press release (3 June 2010). "Nexans Completes Subsea Cable Link to Provide Reliable Power for Pemba Island in Zanzibar – New 25 MVA Link to Mainland Grid Has Enabled the Local Population to End Years of Dependence on Unreliable Diesel Generators" Archived 5 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Nexans. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Reliable electricity attracts investors to Pemba" Archived 22 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Norway: The Official Site in Tanzania, 28 January 2011.

- ^ Staff (30 May 2008). "Melting in Zanzibar's Blackout". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ O'Connor, Maura R. (1 April 2010; updated 30 May 2010)."Zanzibar's Three-Month Blackout – Indian Ocean islands Go for 90 Days Without Power, Causing Business Problems and Water Shortages" Archived 31 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalPost. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "MZF | About Zanzibar". www.mzfn.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ a b Yusof, Issa (17 October 2012). "Malindi Port Gradually Sinking". Daily News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013.

- ^ Staff (29 November 2008). "Zanzibar (Malindi) Nears Completion" Archived 9 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, World Cargo News. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Zanzibar to build modern passenger port at Mpigaduri". The Citizen. Nation Media Group. 9 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Hutson, Terry (30 July 2009). "Fire Guts Passenger Ferry in Dar es Salaam" Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ports & Ships Maritime News. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Sadallah, Mwinyi (16 October 2011). "Confirmed: 2,900 People Died in Zanzibar's Ferry Tragedy" Archived 12 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. IPP Media. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Sadallah, Mwinyi (21 January 2012). "Nine Charged over MV Spice Islander Sinking" Archived 22 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, IPP Media. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Staff (19 July 2012). "Zanzibar Ferry Disaster: Hopes Fade for Missing" Archived 20 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Yussuf, Issa (12 October 2012). "Tanzania: Overloading Blamed for Ill-Fated Boat" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Daily News (via AllAfrica.com). Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Daily Flights to Zanzibar". AuricAir Services Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Zanzibar". Coastal Aviation Limited. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "International [Flight Network]". Ethiopian Airlines. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Book Cheap Flights to Africa". Kenya Airways. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "The House of Wonders Museum of History & Culture of Zanzibar & the Swahili Coast". Department of Archives, Museums and Antiquities. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012.

- ^ Bakari, Mohammed Ali (2001). The Democratisation Process in Zanzibar: A Retarded Transition. GIGA-Hamburg. ISBN 978-3-928049-71-9. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Mass Media, Towards the Millennium: The South African Handbook of Mass Communication Archived 12 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Arrie De Beer, J.L. van Schaik, 1998, page 56

- ^ Martin Stumer, "The Media History of Tanzania", Salzburg, Austria: Ndanda Mission Press, 1998, pp. 191, 194, 295.

- ^ Karume House: Television Zanzibar Archived 3 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ AM radio stations in Tanzania: Directory of AM radio stations in Zanzibar West region Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FM radio stations in Tanzania Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Education in Zanzibar – Southern and Eastern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality". Sacmeq.org. Archived from the original on 2 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Tanzania Commission for Universities Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "SUZA website". Suza.ac.tz. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Higher education – zanzibar.go.tz Archived 7 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tanzania entry – SACMEQ". Sacmeq.org. Archived from the original on 2 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "?". 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "Simba face Tusker in Mapinduzi Cup". supersport.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ "Other matches played on Scyyid Khalifa Ground, Zanzibar". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "New efforts to revive cricket in Zanzibar". Zan Journal. 16 June 2022. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Abdulrazak Gurnah – Literature". literature.britishcouncil.org. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.