United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara

| |

Location of Western Sahara in North Africa | |

| Abbreviation | MINURSO |

|---|---|

| Formation | 24 April 1991 |

| Type | Peacekeeping Mission |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Laayoune, Western Sahara |

Head | Alexander Ivanko (Russia), Special Representative |

Force Commander | Major General Fakhrul Ahsan |

Parent organization | United Nations Security Council |

| Website | minurso.unmissions.org |

| Part of a series on the |

| Western Sahara conflict |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Regions |

| Politics |

| Clashes |

| Issues |

| Peace process |

The United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (Arabic: بعثة الأمم المتحدة لتنظيم استفتاء في الصحراء الغربية; French: Mission des Nations Unies pour l'Organisation d'un Référendum au Sahara Occidental; Spanish: Misión de las Naciones Unidas para la Organización de un Referéndum en el Sáhara Occidental; MINURSO) is the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Western Sahara, established in 1991 under United Nations Security Council Resolution 690[1] as part of the Settlement Plan, which had paved way for a cease-fire in the conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front (representing the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic) over the contested territory of Western Sahara (formerly Spanish Sahara).

MINURSO's mission was to monitor the cease-fire and to organize and conduct a referendum in accordance with the Settlement Plan, which would enable the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara to choose between integration with Morocco and independence. This was intended to constitute a Sahrawi exercise of self-determination, and thus complete Western Sahara's still-unfinished process of decolonization (Western Sahara is the last major territory remaining on the UN's list of non-decolonized territories.)

Mandate

[edit]According to the United Nations, MINURSO was "originally mandated in accordance with the settlement plan to:

- monitor the ceasefire;

- verify the reduction of Moroccan troops in the Territory;

- monitor the confinement of Moroccan and Frente Polisario troops to designated locations;

- take steps with the parties to ensure the release of all Western Saharan political prisoners or detainees;

- oversee the exchange of prisoners of war, to be implemented by International Committee of the Red Cross, (ICRC);

- repatriate the refugees of Western Sahara, a task to be carried out by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR);

- identify and register qualified voters;

- organise and ensure a free and fair referendum and proclaim the results;

- reduce the threat of unexploded ordnances and mines."[2]

Plans

[edit]The independence referendum was originally scheduled for 1992, but conflicts over voter eligibility prevented it from being held. Both sides blamed each other for stalling the process. In 1997, the Houston Agreement was supposed to restart the process, but again failed. In 2003, the Baker Plan was launched to replace the Settlement Plan, but while accepted by the Polisario and unanimously endorsed by the United Nations Security Council, it was rejected by Morocco. Morocco insisted that all inhabitants of the territory should be eligible to vote in the referendum. Following the 1975 Green March, the Moroccan state has sponsored settlement schemes enticing thousands of Moroccans to move into the Moroccan-occupied part of Western Sahara (80% of the territory). By 2015, it was estimated that Moroccan settlers made up at least two thirds of the 500,000 inhabitants.[3]

Presently, there is no plan for holding the referendum, and the viability of the cease-fire is coming into question.

Extensions

[edit]The MINURSO mandate has been extended 47 times since 1991.[4] In October 2006 the Security Council passed a resolution extending the mandate of MINURSO to April 2007.[5] A provision decrying human rights abuses by Morocco in Western Sahara had the backing of 14 members of the Security Council, but was deleted due to French objections.[6]

In April 2007 the resolution extending the mandate to October took "note of the Moroccan proposal presented on 11 April 2007 to the Secretary-General and welcoming serious and credible Moroccan efforts to move the process forward towards resolution" and also took "note of the Polisario Front proposal presented on 10 April 2007 to the Secretary-General".[7] The representative of South Africa took exception to the way that one proposal was held more worthy than the other as well as the lack of participation outside the Group of Friends in the drafting of the resolution.[8]

The October 2007 resolution extending the mandate to April 2008 contained the same preferential wording in its description of the two proposals.[9] The representative of South Africa commented on this again, and regretted the fact that the resolution "considered" rather than "welcomed" the report on the situation by the Secretary-General—"presumably because [it] dared to raise the issue of the human rights violations against the Saharawi people", and quoted the warning in the report[10] about there being no mandate to address the issue of human rights.[11]

The April 2008 resolution extended the mandate for a full year to April 2009.[12] Before the vote, the representative of Costa Rica expressed his "concern at the manner in which the draft resolution on which we are about to vote was negotiated" and a "difficulty in understanding the absolute refusal to include" references to human rights.[13] MINURSO's budget is roughly 60 million dollars per year.[14]

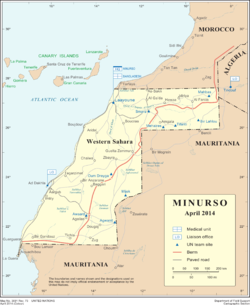

Bases

[edit]There are two sets of teams, those in the Moroccan-controlled portion west of the berm and those in the Sahrawi-controlled region and refugee camps to the east and in Algeria. The camps west of the berm are located in Mahbes, Smara, Umm Dreiga and Auserd. The eastern camps include Bir Lehlou, Tifariti, Mehaires, Mijek, and Agwanit. There is also a liaison office in Tindouf which serves as a communication channel with POLISARIO leadership.

Current composition

[edit]As of 30 June 2018[update], MINURSO had a total of 220 uniformed personnel, including 19 contingent troops, 193 experts on mission, 7 staff officers, and 1 police officer,[15] supported by 227 civilian personnel, and 16 UN volunteers. Major troop contributors are Bangladesh, Egypt, and Pakistan. Armed contingents patrol the no man's land that borders the Moroccan Wall, to safeguard the cease-fire.

- Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Chief of Mission: Alexander Ivanko (

Russia)

Russia) - Force Commander: Major general Fakhrul Ahsan (

Bangladesh)

Bangladesh) - Chief of Mission Support: Veneranda Mukandoli-Jefferson (

Rwanda)

Rwanda) - Chief of Staff: Nick Birnback (

United States)

United States) - Head of Liaison Office, Tindouf: Yusef Jedian (

Palestine)

Palestine)

Other personnel:

| State | Contingent Troops | Experts on Mission | Staff Officers | Police | Total |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 19 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 27 | |

| 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 19 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 15 | |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 19 | 193 | 7 | 1 | 220 |

There have been a total of 16 fatalities in MINURSO: six military personnel, a police officer, a military observer, three international civilian personnel, and five local civilian personnel.[16]

Criticism

[edit]MINURSO is the only UN peacekeeping mission established since 1978 to be operating without the capacity to monitor human rights.[17] Although Resolution 1979 of the UN Security Council recommends the establishment of one, this has not yet happened.[18] In 1995, MINURSO's inability or unwillingness to act against perceived Moroccan manipulation of the process, and abuse of Sahrawi civilians, caused its former deputy chairman Frank Ruddy to deliver a strong attack on the organization;[19] he has since kept up his critique of what he argues is an economically costly and politically corrupt process.[20] Growing criticism has been voiced against the UN Security Council for not establishing a program of human rights (as MINURSO is the only UN mission in the world who has no mandate on them) monitoring for Western Sahara and the Sahrawi population,[21] despite serious reports of numerous abuses.[22] This possibility has been denied by France with its veto power on the Security Council.[23] In April 2016, Uruguay and Venezuela expressed their dissatisfaction with this state of affairs by taking the rare step of voting against a Security Council Resolution reauthorizing MINURSO, United Nations Security Council Resolution 2285, from which Russia and two other powers abstained.

Over a two-year period, mostly 2006–2007, MINURSO personnel vandalized archaeological sites by spraying graffiti over prehistoric rock paintings and engravings[24] in the Free Zone (POLISARIO-controlled parts of Western Sahara). There are also accusations of looting of prehistorical paintings by individuals from the UN on some of those sites.[25]

In May 2010, the Polisario Front suspended contacts with the MINURSO, because of the failure on implementing the self-determination referendum, and accused the force of "...turning into a protector shield of a colonial fact, the occupation of the Western Sahara by Morocco".[26]

See also

[edit]- Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Western Sahara

- Foreign relations of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

- History of Western Sahara

- Politics of Western Sahara

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1720

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 2285

References

[edit]- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 690. S/RES/690(1991) 29 April 1991. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ "MINURSO: Mandate". United Nations. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Shefte, Whitney (6 January 2015). "Western Sahara's stranded refugees consider renewal of Morocco conflict". the Guardian. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Security Council Resolutions and Statements". MINURSO. 2016-10-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1720. S/RES/1720(2006) 31 October 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ "UN shuns W. Sahara rights plea after France objects". Reuters Alertnet. Reuters. Retrieved 2006-10-31.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1754. S/RES/1754(2007) 31 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 5669. S/PV/5669 page 2. Mr. Kumalo South Africa 30 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Document 619. S/2007/619 (2007) Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Document 619. Report of the Secretary-General on the situation concerning Western Sahara S/2007/619 page 15. 19 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 5773. S/PV/5773 page 2. Mr. Kumalo South Africa 31 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1813. S/RES/1813(2008) (2008) Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 5884. S/PV/5884 page 2. Mr. Urbina Costa Rica 30 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ "Financial aspects". MINURSO Facts and Figures.

- ^ "Troop and police contributors". United Nations Peacekeeping. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Fatalities". United Nations Peacekeeping. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Mission Mandate". Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ^ "United Nations Security Council Resolution 1979". Resolutions of the Security Council on MINURSO.

- ^ Ruddy, Frank (1995-01-25). "Review of United Nations Operations & Peacekeeping". Washington, DC: Congress of the United States. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ Catherine, Edwards (1999-10-04). "Saharawi Republic Waits to Be Born". B Net. Archived from the original on 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ Whitson, Sarah Leah (2009-04-17). "Letter to the UNSC urging for human rights monitoring in Western Sahara". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ https://www.afapredesa.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=233&Itemid=2 Campaña internacional ampliación D.D.H.H. mandato MINURSO

- ^ "Security Council under pressure over human rights in Western Sahara" Pravda, April 27, 2010

- ^ "UN vandals spray graffiti on Sahara's prehistoric art". The Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "Cronaca: UN peacekeepers: Cultural crime, too". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2010. UN peacekeepers: cultural crime, too.

- ^ "El Polisario rompe los contactos con la MINURSO" (in Spanish). El País. 2010-05-28. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Western Sahara: Anatomy of a Stalemate by Erik Jensen, former director of MINURSO (1995–1998) (ISBN 1-58826-305-3)

- Peacemonger by Marrack Goulding, former director of UN peace-keeping missions (ISBN 0-8018-7858-6)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- UN homepage SC-resolution 1541 with background info

- A collection of UN documents regarding MINURSO (in French)

- Damage to rock art sites attributed to MINURSO in Western Sahara between 1995 and 2007