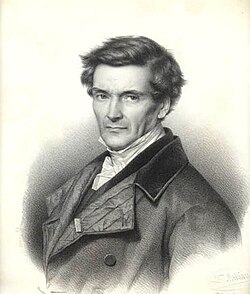

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis | |

|---|---|

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis | |

| Born | 21 May 1792 Paris, France |

| Died | 19 September 1843 (aged 51) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique |

| Known for | Coriolis effect Differential analyser Integraph Kinetic energy |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, Physics |

| Institutions | École Centrale Paris École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées École Polytechnique |

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis (French: [ɡaspaʁ ɡystav də kɔʁjɔlis]; 21 May 1792 – 19 September 1843) was a French mathematician, mechanical engineer and scientist. He is best known for his work on the supplementary forces that are detected in a rotating frame of reference, leading to the Coriolis effect. He was the first to apply the term travail (translated as "work") for the transfer of energy by a force acting through a distance, and he prefixed the factor ½ to Leibniz's concept of vis viva, thus specifying today's kinetic energy.[1]

Biography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

Coriolis was born in Paris in 1792. In 1808 he sat the entrance exam and was placed second of all the students entering that year, and in 1816, he became a tutor at the École Polytechnique, where he did experiments on friction and hydraulics.

In 1829, Coriolis published a textbook, Calcul de l'Effet des Machines ("Calculation of the Effect of Machines"), which presented mechanics in a way that could readily be applied by industry. He established the correct expression for kinetic energy, ½mv2, and its relation to mechanical work.

During the following years, Coriolis worked to extend the notions of kinetic energy and work to rotating systems.[2] The first of his papers, Sur le principe des forces vives dans les mouvements relatifs des machines (On the principle of kinetic energy in the relative motion in machines),[3] was read to the Académie des Sciences (Coriolis 1832). Three years later came the paper that would make his name famous, Sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps (On the equations of relative motion of a system of bodies).[4] Coriolis's papers do not deal with the atmosphere or even the rotation of the Earth, but with the transfer of energy in rotating systems like waterwheels. Coriolis discussed the supplementary forces that are detected in a rotating frame of reference and he divided these forces into two categories. The second category contained the force that would eventually bear his name. A detailed discussion may be found in Dugas.[5]

In 1835, he published a mathematical work on collisions of spheres: Théorie Mathématique des Effets du Jeu de Billard, considered a classic on the subject.[6][7]

Coriolis's name began to appear in the meteorological literature at the end of the 19th century, although the term "Coriolis force" was not used until the beginning of the 20th century. Today, the name Coriolis has become strongly associated with meteorology, but all major discoveries about the general circulation and the relation between the pressure and wind fields were made without knowledge about Gaspard Gustave Coriolis.

Coriolis became professor of mechanics at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in 1829. Upon the death of Claude-Louis Navier in 1836, Coriolis succeeded him in the chair of applied mechanics at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and to Navier's place in the Académie des Sciences.[8] In 1838, he succeeded Dulong as Directeur des études (director of studies) in the École Polytechnique.

He died in 1843 at the age of 51 in Paris. His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

-

1829 copy of "Du Calcul de L'Effet Des Machines"

-

Introductory page of an 1829 copy of "Du Calcul de L'Effet Des Machines"

-

First page of an 1829 copy of "Du Calcul de L'Effet Des Machines"

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jammer, Max (1957). Concepts of Force. Dover Publications, Inc. p. 167; footnotes 12, 14. ISBN 0-486-40689-X.

- ^ Charles Coulston Gillispie (2004). Science and Polity in France: The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Years. Princeton University Press. p. 693. ISBN 0-691-11541-9.

- ^ G-G Coriolis (1832). "Sur le principe des forces vives dans les mouvements relatifs des machines". Journal de l'École Royale Polytechnique. 13: 268–302.

- ^ G-G Coriolis (1835). "Sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps". Journal de l'École Royale Polytechnique. 15: 144–154.

- ^ Rene Dugas (1988). translated by J. R. Maddox (ed.). A History of Mechanics (Reprint of 1955 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 374. ISBN 0-486-65632-2.

- ^ Robert Byrne (1990). Byrne's Advanced Technique in Pool and Billiards. Harcourt Trade. p. 49. ISBN 0-15-614971-0.

- ^ G Coriolis (1990). Théorie mathématique des effets du jeu de billard; suivi des deux celebres memoires publiés en 1832 et 1835 dans le Journal de l'École Polytechnique: Sur le principe des forces vives dans les mouvements relatifs des machines & Sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps (Originally published by Carilian-Goeury, 1835 ed.). Éditions Jacques Gabay. ISBN 2-87647-081-0.

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness (1990). Convolutions in French Mathematics, 1800–1840: From the Calculus and Mechanics to Mathematical Analysis and Mathematical Physics. Birkhäuser. p. 1052. ISBN 3-7643-2238-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Persson, A., 1998 How do we understand the Coriolis Force? Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 79, 1373–1385.

374 KB PDF document of the above article

External links

[edit]- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- "Sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps" (Coriolis, 1831 & 1835), online and analyzed on BibNum [click 'à télécharger' for English version]

- "Sur le bruit du tonnerre" (Coriolis, 1833), online and analyzed on BibNum Archived 2022-09-01 at the Wayback Machine [click 'à télécharger' for English version]